The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 16 January 2026 11:37 am It was a confounding, frustrating season even before we learned it would be a fracture in the Mets’ timeline, with stalwarts we’d grown used to shipped off or allowed to depart and their replacements still yet to take shape. One day it will all seem like a logical story; for now it’s just baffling. But onward we go, in good times and bad as well as times we’re not sure about yet, so it’s time to take stock of the season’s matriculated Mets.

(Background: I have three binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Francisco Alvarez is Class of ’22, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who didn’t play for the Mets, manage the Mets, or get stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.)

Welcome to the study rug, fellas! (If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Off we go into the wild blue and orange yonder….

Juan Soto: It all seemed a little underwhelming somehow. Some of that was gigantic expectations — 15 years, $765 million tends to drown out everything else — and some of that was the season’s curdling into murkiness and then disaster. Soto wound up with 43 homers and 105 RBIs, which is pretty far from a down season, so maybe it’s us. Or maybe it’s that by now we’re braced for impact when it comes to the first season for a high-profile acquisition — ask Carlos Beltran or Francisco Lindor about that. (Hey, their later years turned out pretty well!) Soto’s Met career got off to what in hindsight should have felt like a foreboding note: On Opening Day he came up against Josh Hader with two out in the ninth, runners on first and third, the Mets down a pair of runs and a storybook ending set to be written … and struck out. On the other hand, Soto turned into a base-stealing machine, swiping 38 bags after never stealing more than 12. If you’d like more foreboding, though, that came under the tutelage of Antoan Richardson, who was allowed to go work for the Braves as one of the Mets’ offseason subtractions. Soto gets a 2025 Topps card, which is its own oddity: He’s Photoshopped into an old-style Mets away uniform, which he never wore because the team ditched that classic design for something that looks like it was made in a basement on Canal Street. Good Christ, I have to write how many more of these?

Clay Holmes: Hey, it wasn’t his fault. The hulking former Yankee reliever pitched pretty well as a Mets starter, aside from fatigue that had to be expected given a difficult shift in responsibilities. He saved his best moment for last, coming up big in a Game 161 wipeout of the Marlins. Unfortunately, there was a game the next day too, one that Holmes could only watch. 2025 Topps card.

Hayden Senger: Not all MLB success stories are glittering ones, nor need to be. Senger was drafted in 2018’s 24th round, which no longer exists, and hadn’t exactly got rich as a pro ballplayer: He spent last offseason getting up at 5 am to stock shelves at Whole Foods. He entered 2025 as a glove-first minor-league catcher, the kind of CV that often lacks that final call to the Show, as MLB teams have a maddening habit of finding backup catchers on other MLB rosters instead of in their own ranks. But Francisco Alvarez’s broken hamate bone opened the door for Senger to make the Opening Day roster. His debut came in that fateful ninth inning that ended with a K for Soto; shortly before that Senger was sent to the plate against Hader with the bases loaded and nobody out, looked overmatched, and struck out. He didn’t do much at the plate the rest of the year either, but try and tell him the year wasn’t a success. Topps Heritage card using the ’76 design. 1976 was the first year I collected cards, so the Michigan blue and yellow chosen for the Mets back then look right to me even though I know they aren’t.

A.J. Minter: A burly, bearded ex-Brave, Minter was brought in to give the Mets a reliable lefty arm in the pen and pitched pretty well in April. But in his 13th appearance, he delivered a ball in Washington and came off the mound with an arm shake and a grimace. He’d torn his lat, ending his season and starting a sad parade of injuries to bullpen lefties. Safe to say that wasn’t the plan. Topps gave Minter a Heritage card in its High Numbers series, preventing me from having to admit him to The Holy Books as a Brave.

Griffin Canning: An Angels reclamation project (honestly that sounds like a redundancy these days), Canning looked like a successful Mets reinvention along the lines of Sean Manaea and Luis Severino, riding a reconfigured pitch mix to early-season success. He became an early favorite of mine, too: I loved his mechanics, which were beautifully fluid while also admirably compact. Then it all came crashing down: In late June Canning watched from the mound as Lindor fielded a grounder and by the time the ball smacked into Pete Alonso’s glove, he’d crumpled as if shot and was lying on the infield grass. It was a ruptured Achilles, and the end of his season. Topps Heritage card.

Jose Siri: Siri built a reputation in Tampa Bay as a flashy center-field wizard who struck out a ton but could also hit balls to the moon, but it all went wrong very quickly as a Met: Two weeks into the season, after indeed striking out a ton, Siri fouled a ball off his shin, an innocuous mishap that turned out to be a fractured tibia. He was rusty when he returned in September and endured a nightmare game at Citi Field: Over the course of four pitches, a ball popped in and out of Siri’s glove, ending up as a double, and a bad route turned a single into a triple. Two ABs later, Siri came to the plate with boos raining down and was promptly zapped with a pitch-clock violation. He struck out in that AB, struck out in his next one, and was then pinch-hit for Cedric Mullins, whose arrival was greeted with cheers. (Mullins then … wait for it … struck out.) Siri never had another AB as a Met; he ended up with an .063 average, two hits, and having to remember that fans actually preferred seeing Mullins trudge to the plate instead of him. Now that’s a bad year. Topps Photoshopped him into a Mets uniform for Heritage; they should have added a bag over his head.

Max Kranick: A postseason ghost in 2024, Kranick became corporeal in April and earned early plaudits as a courageous reliever with a talent for wiggling out of tough spots. Unfortunately April was a small sample size; Kranick fell back to Earth in May, got sent down, and soon needed a second Tommy John surgery. Old Topps card as a Pirate.

Justin Hagenman: Turns out his first outing was his best one. Hagenman was pressed into service against the Twins in a mid-April bullpen game and did yeoman work, at least until his statistical line was blemished by after-the-fact crumminess from Jose Butto. (You may remember this game as an early installment in one of my least-favorite 2025 serials, The Revenge Tour of Harrison Bader.) Hagenman appeared now and then later during the season, mostly in mop-up duty. Hey, it’s a living. Topps Heritage card.

Jose Azocar: Collected some hits in April as a fourth outfielder, went zero for May, and became a Brave in June. Have to confess I remember none of that. 2024 Topps card as a Padre.

Jose Urena: A lion-maned veteran reliever, Urena logged one day as a Met, pitching not particularly well during a laugher against the Nats but still earning a save because that’s what the rulebook says. He then spent May as a Blue Jay, June as a Dodger, August as a Twin and September as an Angel. Wheeee! He’s now a Rakuten Golden Eagle. Double wheeee! Old Topps Heritage card as a Padre, one of the few things he wasn’t in 2025.

Kevin Herget: Herget took the baton from Urena in the middle-reliever parade of guys you probably don’t remember either. Middle relief has always been a spaghetti at the wall business, but new rules about options have made managing the last bullpen slots truly ruthless, with teams content to bring a guy up, put him on waivers or release him, then reclaim him after another team’s done the same. The Mets plucked Herget out of the Brewers’ farm system in the 2024 offseason, called him up for a lone appearance at the end of April, put him on waivers, watched (maybe) from afar as he made a lone appearance for the Braves, claimed him from the Braves, used him in five games over three months, made him a free agent at the end of September, then signed him again a week before Christmas. Harget went to Kean University; I own a Kean University beach towel though I have no idea how it came into my possession. Some old card as a (Springfield) Cardinal.

Brandon Waddell: A lefty journeyman who’d pitched in both Korea and China, Waddell stood out (mildly) from the relief mob by logging 11 appearances and being at least reliable-adjacent. Which means you’ll see him again in some uniform next year — possibly even ours — and for whatever subsequent years he shows up and demonstrates that he’s still left-handed. Syracuse Mets card.

Chris Devenski: I first saw him at an unseasonably warm end-of-April bullpen game and my reaction was, “Who the heck is that? When did they call this guy up?” Such are the joys of the reliever parade. Devenski’s end-of-season numbers wound up being pretty good, or at least good enough to get a contract with the Pirates for 2026. Syracuse card.

Genesis Cabrera: Best known for throwing a pitch that hit J.D. Davis in the ankle during a feisty Mets-Cardinals game back in 2022, the prelude to Yoan Lopez drilling Nolan Arenado and a lot of pushing and shoving that saw Alonso tangle with Cabrera and the immortally monikered Stubby Clapp. Honestly that was more memorable than anything Cabrera did in six up-and-down appearances for the Mets in May as they looked for a lefty to replace Danny Young, who’d replaced Minter. Cabrera then collected 2025 paychecks from the Cubs, Pirates and Twins, AKA the Full Urena. Let’s use Cabrera’s Mets tenure as an opportunity to celebrate the inexplicably Canadian Stubby Clapp, whose father and grandfather also went by Stubby; as does his oldest son; and whose wife is named Chastity Clapp. I am not making any of that up. Syracuse card issued after Cabrera had come and gone.

Blade Tidwell: Once a moderately heralded Mets pitching prospect, Tidwell made his debut in May against the Cardinals and it was a pretty typical maiden voyage: some pitches made and some not made on the way to an ugly bottom line that wasn’t as bad as the numbers, provided you squinted a little. Subsequent outings required more squinting and the Mets shipped Tidwell to the Giants at the trade deadline along with Butto and Drew Gilbert. Tidwell’s still young and finding his way, but that felt like the opposite of an endorsement. 2025 Topps card.

Austin Warren: There are 1,450+ innings in a big-league season and it takes a lot of arms to get through them. This bit of wisdom appears in every THB chronicle, because it’s true. Nothing personal, Austin. Syracuse card.

Jose Castillo: A husky lefty reliever, Castillo’s road to the Mets was a bit odd: He imploded against them in late May while pitching for the Diamondbacks and was wearing blue and orange a little more than a week later. Since the beginning of September he’s been employed by the Mariners, the Orioles, the Mets again and is now a free agent. I suppose this is why middle relievers rent instead of buying. A card as an El Paso Chihuahua, which I feel bad about but was the best I could do.

Jared Young: Once-upon-a-time Cubs prospect came over to the Mets after stop-offs in Memphis and Korea and didn’t leave much of an impression. One of a growing number of ballplayers who sneak into Topps sets with autograph-only cards, yet another sign of civilization’s rot. Syracuse card.

Justin Garza: Five June appearances, none of which I remember. A 2025 minor-league card as a … I have no idea what team this is, actually. At least he’s not a Chihuahua.

Tyler Zuber: Pitched two not very good innings for the Mets in June, became a Marlin, and returned to Citi Field at the end of August to face his old team during Jonah Tong’s debut. I was in the stands and registered Zuber’s arrival but had completely forgotten his approximately 20 minutes of Mets service time. Zuber then gave up seven earned runs in a single inning, which I suppose is one way to be memorable. If you’re curious, yes, he displaced Don Zimmer and is currently the 1,287th and last man on the all-time Mets A-Z roster. Syracuse card.

Frankie Montas: Montas looked solid against the Mets as a Brewer in the 2024 wild card series, possibly leading to his signing a two-year deal with New York. It didn’t exactly work out, as Montas was felled by a torn lat in spring training and then pitched abysmally while rehabbing at Triple-A. With no real alternatives, the Mets summoned him to start against the Braves in late June. That went well, but his next start was a shellacking in Pittsburgh (I was lucky enough to see it in person) and he then alternated pedestrian outings with getting lit up, followed by exile to the bullpen. His year ended with the revelation that he needed Tommy John surgery; he was DFA’ed and will get paid $17 million to be hurt next year. 2025 Topps card.

Richard Lovelady: Mets fandom had a titter over the veteran lefty going by “Dicky,” though I wonder if Richard “Stubby” Clapp wanted a word. (Stubby Clapp, unexpected star of the THB Class of 2025!) Exactly what the newest Met wanted to be called led to a spirited discussion on SNY, with Gary Cohen’s eyebrow audibly arched (no really, you could hear it) and someone in the truck presumably told to be aggressive about cutting Keith Hernandez’s mic. Whatever those on a first-name basis called him, Lovelady spent the summer appearing and disappearing from the roster, with not particularly impressive numbers. The Mets must have liked something they saw, though, as they made him their first offseason free-agent signing. Old Topps Heritage card as a Royal.

Jonathan Pintaro: A flaxen-haired reliever who’d opened eyes in indy ball, Pintaro was cuffed around by the Braves in his lone MLB appearance, with Edwin Diaz forced to ride to the rescue at the tail end of a not particularly close game. This is an inherent unfairness of The Holy Books: Pintaro could spend a decade as a reliable contributor and still be stuck with this sour cup of coffee as his entry. Here’s hoping he makes this more than a theoretical injustice. 2025 card as a Binghamton Met.

Colin Poche: I was in the park for Poche’s lone appearance, the middle game of the series in which the Mets stepped on about 50,000 rakes while getting swept by the Pirates. Poche relieved Huascar Brazoban and turned a narrow Pittsburgh lead into an impossibly wide gulf. That sucked, but it isn’t what annoys me most about Poche. That would be his pain-in-the-ass baseball cards. He has a 2020 Chrome autograph card and a 2023 Tampa Bay team-set card, both nonstandard; I wound up needing two copies of the former and haven’t been able to secure the latter. Fortunately this hasn’t cost a lot, since Colin Poche cards aren’t a particularly hot commodity, but I’ve now conservatively spent 10 times the duration of his ineffective Mets tenure trying and failing to secure his annoying baseball cards.

Zach Pop: Another one-gamer, Pop’s second pitch as a Met became a home run onto the Soda Plateau for fucking Austin Wells, who looks like a guy who pesters other Little League dads about buying an above-ground swimming pool. In all, Pop’s Mets career consisted of nine Yankees faced, five of whom hit safely. Not a way to endear yourself to much of anybody, least of all me. Old Topps card as a Marlin.

Rico Garcia: Garcia made his debut in the same game Pop did, and fared better — enough for the Yankees to grab him off waivers from the Mets eight days later. He appeared in one game for the Yankees, returned to the Mets via a tit-for-tat waiver claim, and was soon an Oriole. If it’s this exhausting for us, imagine what it’s like for actual middle relievers. Syracuse card.

Alex Carrillo: Another example of how you can have a good year without good numbers. Before 2025 Carrillo’s organized-baseball career consisted of a few innings of a rookie ball as a Rangers farmhand in 2019. He then spent four years in indy ball, where work with a pitching lab, better nutrition and an improved workout regimen upped his fastball velocity from the mid-80s to triple digits. An acquaintance of Carlos Mendoza’s saw Carrillo pitch in the Venezuelan winter leagues, which led to a Mets contract and a July call-up. It didn’t go too well — a 13.50 ERA will leave a mark — but it’s still a pretty good story. As for baseball cards, Carrillo doesn’t have any, so I had to make him one.

Gregory Soto: Ryan Helsley and Cedric Mullins caught most of the slings and arrows launched by fans upset about the Mets’ trade-deadline debacle, but Soto was quietly terrible too. His numbers looked good but were fundamentally dishonest, as he specialized in letting inherited runners score, with a side gig of not paying attention when he needed to. (That second-to-last loss against the Marlins … oof.) After the season Soto vamoosed to Pittsburgh; they can fucking have him. Old Topps card as a Tiger.

Ryan Helsley: Mind-bogglingly terrible as a Met, with his maladies mostly blamed on pitch tipping and accompanied by an arglebargle of fancy metrics insisting that he was better than he was, which would have been more convincing without nightly evidence that Helsley was not better than anything except throwing oneself down a flight of stairs. (Maybe not even that.) The Mets didn’t help by stubbornly sticking with Helsley’s entrance extravaganza, so jaw-droppingly high camp that Siegfried and Roy might have suggested dialing it back. Eventually the Mets let Helsley’s nightly failures arrive without a concussive light show; by then we just wanted him to go away. Given the fickle nature of relievers, I’m sure he’ll be just fine for the Orioles next year. I also don’t care. A horizontal Topps Chrome Update card. I hate horizontal cards. It’s perfect.

Cedric Mullins: Arrived from Baltimore and immediately made you wonder if he’d been replaced en route by a defective clone. Mullins hit .182, looked meh in center field, and he played with his head up his ass at key moments — witness the sequence against Washington where Daylen Lile ran into a wall, Luis Torrens raced around the bases to score, but Mullins stood around and then got himself belatedly thrown out at second. (Mullins was given a reprieve and returned to first via some mild ump shenanigans, so of course he immediately got doubled off; if you don’t remember, this was the Jacob Young game, perhaps the most tooth-grinding loss in a season that featured plenty of them.) Mullins is now a Ray; when I heard they’d signed him I went full Gollum: “LEAVE NOW … AND NEVER COME BACK!” Re baseball cards, I generally try to pick cards that make the players look good, with rare exceptions: Vince Coleman looks like he just ate a lemon on his 1992 card, and it’s perfect. Mullins’ Topps Heritage card depicts him in asphalt and purple, wearing a ridiculous oven mitt and the sheepish expression of a man who’s just screwed up, and it’s perfect.

Tyler Rogers: A sidewinding reliever, he got traded on the same day as his identical twin brother, which must have been quite the afternoon for Ma Rogers. It’s probably just lingering dismay over how the season crumbled, but I have to ask if he was actually good for the Mets, or just better than Helsley or Soto. When Rogers signed with the Blue Jays I wasn’t sad but also thought, “Has it gotten so bad that no one wants to be a Met?” Topps Chrome Update card; it’s a horizontal but in this case that actually works.

Nolan McLean: A former two-way prospect, McLean was summoned in mid-August with the Mets once again in freefall and immediately looked like he belonged. He beat the Mariners in his first outing (complete with a nifty behind-the-back grab), the Braves in his second, the Phillies in his third (completing a sweep) and the Tigers in his fourth. He finally took an L in his fifth start, a singularly unlikely 1-0 loss in Philly. McLean’s final line? 5-1 with 57 Ks and 16 walks in 48 innings. That will that play. And the intangibles were impressive too: McLean demonstrated he could size up hitters and exploit them, and proved apt at strategizing on the fly when his pitches proved disobedient. A pitcher to dream on, and one I can’t wait to watch again. Syracuse card; he gets a full-fledged Topps offering next month.

Jonah Tong: A Canadian kid with mechanics that looked like a Xerox of Tim Lincecum’s, Tong blitzed his way through the minors in 2025 after adding a change-up to complement his riding fastball and ungodly curve. Was he ready? Given the Mets’ increasingly shaky playoff hopes, by the end of August it didn’t really matter. Tong’s debut at Citi Field saw the Mets pin 19 runs on Miami, the most runs they’d ever scored in a home game, and a flashback to the 17 they’d bequeathed Mike Pelfrey in his debut. (Somewhere in Texas, Jacob deGrom had to be gritting his teeth.) As it turned out, Tong still had things to learn: Of his four subsequent starts, one was good, one was so-so and two were beatdowns. (The opposing pitcher in one of those beatdowns? Jacob deGrom.) So no, he wasn’t ready, but it’s not on Tong that the Mets asked him to be a miracle worker instead of just a promising rookie pitcher. He’ll take his next steps in February, which should be fun to watch. Topps Pro Debut card, he’ll get something better in 2026 Series 1.

Brandon Sproat: The third member of the Mets’ kiddie pitching corps, Sproat looked very much like a work in progress over his first four big-league starts, which it might have been kinder to have him make in 2026. Again, there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with an initial quartet of appearances yielding the assessment “work in progress” — plenty of solid careers have started with less than that. Here’s hoping that Sproat’s maturation process — and that of his two fellow rookies — includes not letting the stench of his teammates’ failures linger. He deserved better. We all did. Topps Pro Debut card.

Dom Hamel: An August call-up yielded no appearances, making Hamel briefly a Met ghost. He escaped ectoplasm the next month with a lone inning against the Padres in which he yielded three hits but escaped being scored on when Luis Arraez was tagged out at second an eyelash before teammate Elias Diaz (told to slow down by a too cool for school Manny Machado) touched home. That was odd; so was Hamel becoming the 46th pitcher the Mets used in 2025 and thereby setting an MLB record. It’s not a record I expect to last given the newfound roster churn we’ve discussed several times already: Relievers Wander Suero and Dylan Ross weren’t called on during a game and so went into the Holy Books as 2025 Met ghosts instead of the 47th and 48th pitchers used. (Bet they’re disappointed not to have a larger role in this extended meditation on lousiness and failure.) Hamel is now Rangers property, so perhaps his talent for escaping jams is real. Syracuse card.

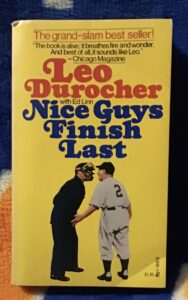

by Greg Prince on 14 January 2026 12:27 am The agate type that used to fill newspapers’ TRANSACTIONS boxes and for all I know still do can change everything — about your team, about the players within, about the course of your expectations and satisfaction as fan. While the Hot Stove barely simmers, Kyle Tucker rumors notwithstanding, I’d like to take this opportunity revisit a few picas worth of Mets transactions through time.

In a particular but not chronological order, nitty-gritty details courtesy of Baseball-Reference…

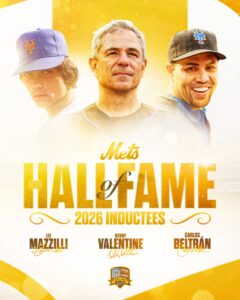

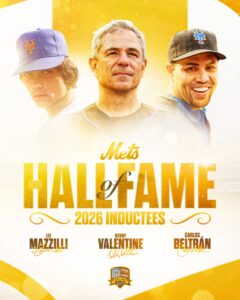

January 13, 2005: CARLOS BELTRAN signed as a free agent with the New York Mets.

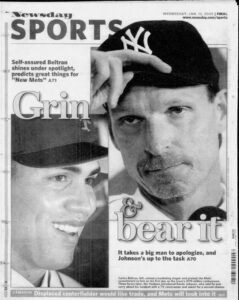

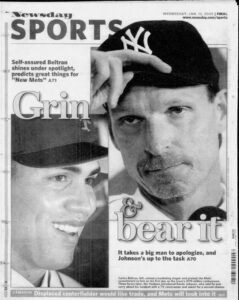

January 13 is the date BB-Ref has for Carlos Beltran signing with the Mets, meaning happy twenty-first anniversary! But it wasn’t January 13, so happy twenty-first-ish anniversary! Maybe January 13 was when the ink officially dried on the contract, but it was learned Beltran was becoming a Met as of the early morning hours of January 9, 2005, shortly after the Jets upset the Chargers in the AFC Divisional playoffs. This, too, was an upset. Beltran seemed likely to either stay in Houston or get paid by the Yankees. Yet Carlos showed up at Shea to join the “New Mets” on January 11, the one day after the Yankees’ consolation prize, Randy Johnson, roughed up a cameraman who had the audacity to film him. Both New York arrivals were on TV that day and in all the papers the next; ours went smoother. By January 13, Beltran’s signing was no longer a bulletin, though the excitement was still fresh. We — the Mets — had lured the biggest, shiniest free agent on the market into our lair. It took a big, shiny, unMetlike offer, but such was tendered and accepted.

Just like that, Carlos Beltran was a New York Met. Just like that, everything Carlos Beltran did or didn’t do became our business. Just like that, we worried about Carlos Beltran, maybe in generous personal “I hope he’s all right” terms, but mostly in transactional “I hope he gets going/stays hot” terms. It is the Transactions box after all.

In 2005, the first year in which Carlos Beltran became our business, business was so-so. Then, from 2006 until he got hurt in the middle of 2009, business mostly boomed, even if things came to a chilling standstill once or twice. He returned to health after about a year and kept going/stayed hot, straight to the moment in 2011 when it seemed to everybody’s benefit to send him on his way. The seven-year contract was about to be up, the Mets were relatively down, and a Beltran could you get you a piece of future. Carlos by this point had put together a very nice Met past, enough to earn him a spot in the team’s Hall of Fame.

On January 20, 2026, the Baseball Writers Association of America vote for the big Hall of Fame will be announced. Carlos Beltran is the institution’s leading candidate. Those who track the publicly shared ballots (publicly shared partly for transparency’s sake and partly because if you’re going to fill column inches amid the Cold Stove portion of winter, how can you pass up a hardy perennial of a topic?) have calculated Beltran is running way past the 75% barrier required for Cooperstown entry. Even if those BBWAA members who are shy about revealing their choices are not as pro-Beltran as their brethren, the Hall appears his imminent destination. Not a surprise if you watched him for his seven Met seasons. From 2005 to 2011, we had ourselves an every-tool craftsman who, all things considered, made the Mets’ investment of $119 million worthwhile. We not only got ourselves a Silver Slugger, a Gold Glover, and perception-changer, we are on the verge of saying we got ourselves a future Hall of Famer whose Met experience is hardly incidental to the qualifications inspiring all those check marks and X’s.

You can’t always say that, no matter how tantalizing the Transactions box looks the instant it is published.

February 10, 1982: GEORGE FOSTER traded by the Cincinnati Reds to the New York Mets for Greg Harris, Jim Kern, and Alex Treviño.

My brother-in-law goes by the familial code name Mr. Stem, denoting that his level of interest in the Mets is the inverse of mine. Yet Mr. Stem comes through every December 31 for my birthday with what he believes are throwaway baseball items. He sees something old somewhere, he scoops it up, he sticks it in a box — after wrapping it exquisitely and numbering it so the entire presentation can be expertly choreographed — and he sends it to me for video unveiling on New Year’s Eve. This is part of our family tradition every December 31 ever since he and my sister moved to the West Coast. That and me good-naturedly (I swear) reminding them that the last year they lived back East, they sent Stephanie and me home well before midnight because they wanted to go to bed.

The arcana he secures is utterly random. Mr. Stem has a narrow frame of baseball reference, but his instinct for the utterly eclectic is so razor sharp that it could be Razor Shines. Pulp novels from the 1940s. Statistical volumes from the 1960s. Out-of-print histories inevitably prefaced with “you probably already have this”. And, once in a while, something that makes me go SQUEE!

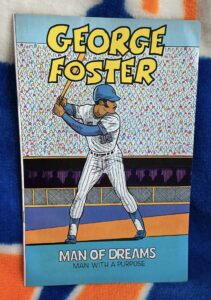

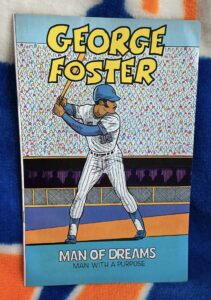

This past birthday, Mr. Stem sent me a comic book with the title George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose.

SQUEE!

GEORGE FOSTER!

A COMIC BOOK VERSION OF GEORGE FOSTER!

GEORGE FOSTER IN A METS UNIFORM ON THE COVER!

GEORGE FOSTER SWINGING A BAT THAT ISN’T HIS TRADEMARK BLACK BAT, DESPITE THE FACT THAT THIS COMIC BOOK IS PUBLISHED BY GEORGE FOSTER ENTERPRISES, INC., THUS YOU’D INFER ACCURACY WOULD BE A GIVEN!

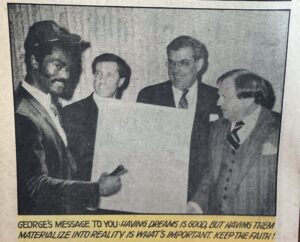

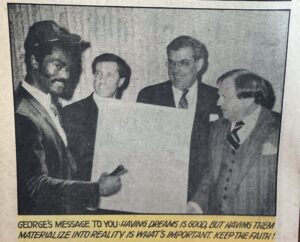

GEORGE FOSTER ACCOMPANIED BY FRED WILPON, NELSON DOUBLEDAY, AND FRANK CASHEN IN THE COMIC BOOK’S FINAL PANEL, NOT DRAWN LIKE THE REST OF THE COMIC BUT PHOTOCOPIED FROM HIS PRESS CONFERENCE WHERE HE’S SIGNING THE CONTRACT THAT’S GONNA MAKE HIM A MET FOR THE NEXT FIVE YEARS, THE MOMENT WHEN EVERYTHING ABOUT GEORGE FOSTER BEING ON THE METS WAS SUCH AN UNSULLIED POSITITVE THAT YOU JUST HAD TO GO OUT AND PUBLISH A COMIC BOOK ABOUT IT!

“If I knew that was going to be such a big hit,” Mr. Stem observed, “I would have saved it for last.”

It was my party and I’d SQUEE! if wanted to. You would SQUEE!, too, if it happened to you.

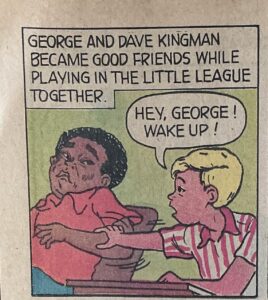

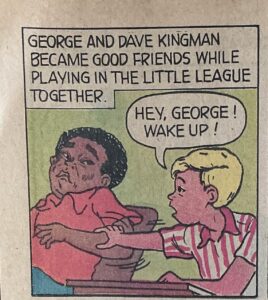

The beauty part of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, besides its existence; its sense of opportunism (revisited four years later when Foster foisted “Get Metsmerized” on the rap-listening Mets fan community); the panel that taught us “George and Dave Kingman became good friends while playing in the Little League together”; and the heroism with which it imbues its lead character as he commences his life journey of learning to take math class seriously so he can calculate his batting average between belting home runs, is its timing. Not just the timing of appearing in my hands weeks after the departures of so many Citi Field stalwarts pushed me into a Metsian funk, but the timing of its publication. George Foster Enterprises, Inc., hustled this comic onto the market in 1982. In 1982, we were ripe for believing George Foster’s purpose meshed with our dreams of making the Mets an overnight contender. We’d be disabused of those dreams before 1982 was over. The beauty part of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, besides its existence; its sense of opportunism (revisited four years later when Foster foisted “Get Metsmerized” on the rap-listening Mets fan community); the panel that taught us “George and Dave Kingman became good friends while playing in the Little League together”; and the heroism with which it imbues its lead character as he commences his life journey of learning to take math class seriously so he can calculate his batting average between belting home runs, is its timing. Not just the timing of appearing in my hands weeks after the departures of so many Citi Field stalwarts pushed me into a Metsian funk, but the timing of its publication. George Foster Enterprises, Inc., hustled this comic onto the market in 1982. In 1982, we were ripe for believing George Foster’s purpose meshed with our dreams of making the Mets an overnight contender. We’d be disabused of those dreams before 1982 was over.

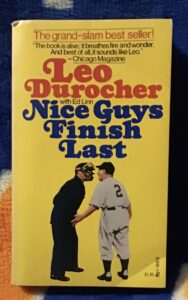

As I descended slightly from my instant euphoria over holding and leafing through a copy of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, I attempted to give my sister and her husband a capsule Metsplanation of the significance of trading for George Foster and shelling out the enormous bucks Cincinnati no longer wished to shell in ’82, which is to say why this comic book got me right in the feels. The Mets, I detailed broadly, had never acquired a player of his caliber, at least not one still more or less in his prime. Foster, I continued, was regularly among the league leaders in all kinds of categories from which the Mets were usually absent. He’d been an MVP not that long before. He was an intrinsic element in something called the Big Red Machine, a contraption that had won championships.

“So what happened when he came to the Mets?” my sister asked.

“He fell of a cliff. Was never as good as he’d been with his old team. Became such an object of disdain that fans outside Shea, when they recognized the stretch limo he took to the ballpark, pelted it with rocks and garbage.”

“Doesn’t that always happen?” A Met trade for a superstar going south, she meant.

I figured I had about thirty seconds more of their attention before their interest on the subject waned and they’d want me to unwrap the next tchotchke, so I condensed it to “not always, but enough to leave that impression.” I figured I had about thirty seconds more of their attention before their interest on the subject waned and they’d want me to unwrap the next tchotchke, so I condensed it to “not always, but enough to leave that impression.”

Left uncited in my summary was the time the Mets traded a superstar of their own and could be said to have gotten the better of the deal. The catch was their transactional victory didn’t emerge as a certifiable Met win for approximately a third of a century.

March 27, 1987: DAVID CONE traded by the Kansas City Royals with Chris Jelic to the New York Mets for Rick Anderson, Mauro Gozzo, and Ed Hearn.

No, George Foster didn’t resemble a comic book hero as a Met, but he was an important building block in who the Mets were going to become. And after the massive disappointment of 1982, he proved intermittently productive over the following three seasons and helped lift the Mets to their outstanding start the year after that, 1986. Then the cliff beckoned again. He fell off it for good by August, no longer contributing to the ballclub that had grown up around him and showing himself unwilling to accept a reduced role now that he was no longer a Man With a Purpose at Shea.

During the years in between the trade for Foster and the release of Foster, the Mets made mostly outstanding trades. I didn’t get into that with the Stems, but we know they did. We also know that on the other side of the championship the Mets won once Foster talked his way out of town, they had one more dynamite deal up their sleeve.

I’m not the only person with a Mets connection who celebrates a birthday right around New Year’s. David Cone was born two days after me. His Mets connection might be stronger than mine.

True, I beat Coney to this earth by approximately 48 hours and to a deep and abiding interest in who the Mets might trade for by many years, but it was me being all “we got who for Ed Hearn?” as Spring Training 1987 wound down, rather than David Cone being all “what do you mean there’s a Mets fan two days older than me who has no prior awareness of my potential as a starting pitcher?” Cone didn’t know who I was when he came over from Kansas City with eleven games’ worth of big league experience, but I learned about him plenty in the seasons to come. Especially in 1988, when he won 20 games for the division-winning Mets. And 1990, when he shut down the Pirates in the final Big Series of the era (9 IP, 1 ER, enormous W). And 1991, when he led the National League in strikeouts for a second consecutive year, capping it with 19 on Closing Day in Philadelphia. And 1992, when he went to his second All-Star Game as a Met. Hearn the backup catcher for Cone the budding ace worked out very well for the Mets. Only problem was Cone, 28 and on the eve of free agency, would now want to get compensated commensurate to his achievements as he approached the next segment of his career.

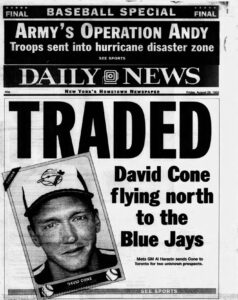

August of 1992 found the Mets nearly two years removed from that final Big Series of the era. Despite the future former ESPN commentator’s electric arm, magnetic presence (maybe sometimes a little too magnetic), and ongoing superbness, the Mets had faded from contention in 1991 and imploded altogether amid an on-the-fly reloading the next season, one of those periods when it becomes reasonable to ask, “Doesn’t that always happen?” Whether it does or not, Al Harazin, the GM who succeeded Frank Cashen, decided to take a different approach. Instead of trading for an established star, he’d trade the one he had who was having a helluva year to a formidable team with championship aspirations..

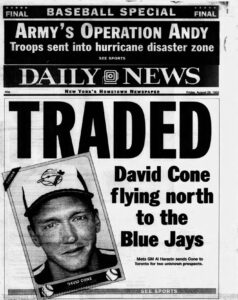

August 27, 1992: JEFF KENT traded by the Toronto Blue Jays with a player to be named later to the New York Mets for David Cone.

We are deep enough into January to take a cue from Larry David and move beyond wishing one another a Happy New Year. The residue from my birthday and David Cone’s birthday has evaporated. We look forward to later January things as January gets going. We, as baseball fans, look forward to the Hall of Fame voting being announced, particularly if we have a rooting interest.

As baseball fans we root for greatness to be properly recognized, but that’s not really our rooting interest when it comes to the Hall of Fame. We root for players we liked when they played and, I’ve come to conclude, we root to tell the Hall of Fame voters they don’t know what the hell they’re doing. On January 20, when the envelope is unsealed on the MLB Network, we might very well cheer that Carlos Beltran has been elected on his fourth ballot; we might offer polite applause if Bobby Abreu or Francisco Rodriguez shows any sign of momentum; we might feel our heart warm if David Wright remains eligible to appear again next year; we will likely be curious to see if Daniel Murphy or Rick Porcello received as much as one vote; and we will certainly be sure somebody is getting overlooked or, worse, overvalued.

The Hall of Fame attempts to honor baseball’s legends, but I’ve become convinced the main reason it’s there is so fans can tell anybody who’ll listen that they’re right and most everybody else with an opinion slightly different from theirs is a clod. Which reminds me — the list of no longer insightful phrases I hope transmit a faint shock to the fingertips of anybody who types them, so as to discourage their rote repletion, now includes:

• “we root for the laundry”;

• “this is why we can’t have nice things”;

• “if the Wild Card existed then, we would have been in the playoffs every year”;

• and, especially in the weeks surrounding New Year’s Eve/Day, “…more like Hall of Very Good”.

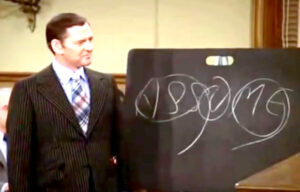

To prepare us in our self-assuredness that we’re right and they’re wrong, the Hall of Fame gives us a test run by announcing its Era Committee decision in December. Different Eras are Committee’d in different Decembers. In December 2025, the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee convened. That’s the one that considers players who shone most brightly from 1980 forward who are no longer eligible to be on the writers’ ballot. The other Era Committee is the Classic Baseball Era Committee, covering the days before 1980. There was a lot of classic baseball played from 1980 forward, and the 1980s aren’t particularly contemporary at this time, but never mind that. Those are the names. And the committee with the contemporary name elected one new Hall of Famer last month.

The guy we got for David Cone. Well, we got two guys for David Cone. One was initially a player to be named later, whose name wasn’t Classic or Contemporary. It was Ryan Thompson. High hopes were attached to Ryan Thompson. They weren’t fulfilled, not when he was a Met, not after he was a Met. It happens. They could have waited to name Ryan Thompson all they wanted. He wasn’t making the Hall of Fame. The guy we got for David Cone. Well, we got two guys for David Cone. One was initially a player to be named later, whose name wasn’t Classic or Contemporary. It was Ryan Thompson. High hopes were attached to Ryan Thompson. They weren’t fulfilled, not when he was a Met, not after he was a Met. It happens. They could have waited to name Ryan Thompson all they wanted. He wasn’t making the Hall of Fame.

Jeff Kent, on the other hand, is a Hall of Famer. The Contemporary Baseball Era Committee says so, and who are we to argue with such a thoroughly named committee? When the news of his 1992 acquisition thrust itself onto my radar, I was being all “we got who for David Cone?” The answer was never — not in the immediate aftermath of the news nor at any juncture of the parts of five seasons he was a Met — “we got a future Hall of Famer for David Cone!” But son of a gun, that’s exactly what we did.

Kent, whom the Baseball Writers Association of America resisted electing for ten winters, was on the committee ballot alongside seven other players. The eight of them all had credentials making them worthy of a second thought, which is the whole idea of these committees. The BBWAA has the definitive word, but not necessarily the final one. Not enough writers opted to ink in an X or check mark next to Kent or the other seven — Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Carlos Delgado, Don Mattingly, Dale Murphy, Gary Sheffield, and Fernando Valenzuela — thus none of them was ever elected during their prime eligibility period. Writers can miss things. Thus, committees, despite their own capability for missing things (like Keith Hernandez’s qualifications), convene and debate and vote.

In December, they voted for Kent in numbers large enough to immortalize him. They voted for Delgado somewhat, but not quite enough to push our former first baseman (another ex-Blue Jay) over the top. This Carlos’s level of support made for a nice refutation of the writers who ignored him his one year as a BBWAA candidate in 2015, even if it was insufficient for 2026 induction. Murphy and Mattingly, arguably the best players in their leagues at their peak, also won measurable if inadequate support. Bonds and Clemens, inarguably the most prolific hitter and pitcher of their and perhaps all time, didn’t get any reported votes, for presumably the same reasons the writers never came close to selecting them. Nothing of note for Sheffield, one of the most dangerous hitters I ever watched, including when he was in his Met twilight; nothing, either, for Valenzuela, a huge star and a great pitcher.

It could be argued Fernando didn’t do what he did so marvelously long enough. It probably was when the committee met. Same for Murphy and Mattingly. The arguing, official and otherwise, seems to the be the point of every aspect of the Hall of Fame selection process. I couldn’t stand Roger Clemens, but I wouldn’t argue he wasn’t a Hall of Famer in terms of performance, however toxically he put together a good bit of it. That’s what makes me less than ideal as a Hall of Fame consumer. I’m not much for arguing against the merits of great baseball players. If they got far enough to be considered anew after the writers said “nah,” they probably had a lot going for them as players. The existing plaques wouldn’t fall down in shame if a new one was added for any of them. Even — yeech — Clemens.

***Jeff Kent of the New York Mets is going into the Hall of Fame. That probably won’t be how he’s introduced the day he’s inducted, yet I love saying it that way. I love saying it that way as much as I will love saying Carlos Beltran of the New York Mets is going into the Hall of Fame, never mind that I doubt I ever exactly loved Jeff Kent on the New York Mets. Truly, I don’t know that I loved Beltran as much as I loved Beltran’s impact on the Mets becoming a serious team heading into ’05; and his role in making them division-winners in ’06; and his keeping the Mets aloft as best he could down the contracting stretches of ’07 and ’08; and all the grace and stoicism he demonstrated until he was swapped to San Francisco for blue-chip prospect Zack Wheeler in ’11. Let’s say I loved admiring Carlos Beltran as a Met.

It takes a ton of retrospect to apply the L-word to Jeff Kent from when he was a Met. I don’t know that I’ve stockpiled enough. If I call him a flagship Met of the years when the Mets were sinking, it comes off as an unintentional insult. Still, I think of him as kind of the personification of his Mets at their striving best. There were days and nights, you thought those Mets could get better. Those were days and nights when you grabbed a peek at Kent, who was 24 when was traded to us, and thought, maybe, just maybe, we can build a little around this guy. And even if we can’t, he’s already here and he’s not really the reason we’re not great.

If it was somewhere between 1992 and 1996 and you were a Mets fan, that’s pretty much what love was.

At his Met best, which covered roughly the middle of 1993 to the middle of 1994 (slashing .302/.362/.511 over the 162 games the Mets played between 6/22/93 and 6/19/94), he was an All-Star caliber second baseman, despite not being named to either year’s squad. He’d get his NL due later, in another uniform, though by then, I’d be feverishly punching out holes next to second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo’s name in my personal quest to see my favorite Met start ahead of everybody else. Fonzie I absolutely loved. He and his team as one century became another inspired torrents of passion.

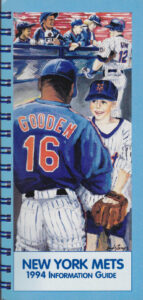

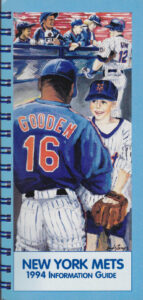

Kent I liked OK when he was going well when he was a Met. He surely had his moments. As illustrated in the above paragraph, he had a solid season’s worth. During the second half of 1993, he set a foreshadowy second baseman home run record (most in a single season by any Met playing the position — 20 overall, 19 in games he manned second, eventually broken by Edgardo). His potential was legitimately encouraging to fans and as well as management. With the Mets aiming to grope their way out of last place and their image-makers wishing to communicate their present included glints of sunlight, they included Kent alongside legend-in-residence Doc Gooden on the cover of their 1994 media guide, Norman Rockwell-style. In the foreground Gooden is signing an autograph for a delighted kid. Behind them is Kent, doing the same for a couple of more kids. It was the Mets’ way of saying we have players you’ve loved and players we think you might like. Not pictured: any Met throwing firecrackers at anybody. The Mets may not have been ready to vault out from under .500, but they were gonna be fairly affable.

They were gonna be better once ’94 got going, and not only because they couldn’t have been much worse than their 59-103 selves. No Met started the new season hotter than Kent, who earned himself NL Player of the Week Honors for the second week of the year, which encompassed five games — but what games! Six homers! Thirteen RBIs! Start the All-Star voting ASAP! If nothing else, Jeff was making some early takes on the trade that brought him to Flushing look vastly premature and more than a little myopic. To be fair, everybody was in shock at the end of August in ’92, and few were in the mood to learn much about the new kid in town.

Still…

“Good Lord. I can’t believe we didn’t get a proven major league player in return.”

—Dave Magadan

“Ever since they let Straw go, nothing surprises me anymore.”

—Gooden

“They had someone who’d proven he could make it in New York, and they let him get away.”

—Cone himself, though he might have been biased

Kent didn’t keep up the offense as 1994 wound down and then disappeared due to a strike. When baseball re-emerged in 1995, the infielder who made strides beyond the assessment that followed his acquisition — “regarded as a solid and versatile player…but not a spectacular one,” per Tom Verducci in Newsday — failed to progress. And any gestating thoughts I (or any Mets fan) might have incubated about Jeff Kent growing into a future Hall of Famer likewise didn’t materialize.

***Jeff Kent is the 17th Met player to be selected to the Hall of Fame as a player, and the first, I believe, of whom it was never thought “he could make the Hall of Fame” while he was a Met. I don’t know to what extent baseball fans and the baseball community let their minds wander before Cooperstown became a year-round conversation-starter (and online civility-killer), but it had to have been commonly understood that a few of the highly decorated veterans who adorned the Mets in the franchise’s early years certainly had built careers that could conceivably get them enshrined. Tell the denizens of the Grandstand at the doomed Polo Grounds or the Mezzanine of sparkling Shea Stadium amid all the losses from 1962 to 1965 that in Richie Ashburn, Gil Hodges, Duke Snider, Warren Spahn, and Yogi Berra they were glimpsing five eventual Hall of Famers in action (being managed by a Hall of Famer in Casey Stengel, no less), and it might not have jibed with the results on the field, but I can’t imagine there would have been massive pushback. Yeah, those Mets had some great players, albeit after they were done routinely playing at their greatest.

Tom Seaver came along and created a Hall of Fame résumé right before our eyes. Nolan Ryan went to Anaheim and did the same, packing with him what surely somebody between 1966 and 1971 referred to in Queens as Hall of Fame stuff. Willie Mays was Willie Mays. Gary Carter was on the road to Cooperstown the day he became a Met; the championship he helped lead us to allowed him to access the express lane, even if the writers made him sit through six ballots’ worth of traffic. Eddie Murray, who did not elevate the Mets by force of his bat and personality, would pay no penalty for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, having already stamped his first-ballot ticket in Baltimore.

Mike Piazza was a megastar who became larger than life as a Met. Rickey Henderson was on Mount Rickey forever. Roberto Alomar and T#m Gl@v!ne, not personal favorites, couldn’t be denied their destiny. We knew they were “future Hall of Famers,” which made their middling fits (to put it kindly) all the more vexing. Pedro Martinez, who became a personal favorite while in our midst, might as well have signed kids’ programs with “HOF” after his name the moment he came here. Billy Wagner someday becoming a Hall of Famer didn’t seem illogical as he manned the Met mound, even on those occasional afternoons when saves eluded his grasp.

But Jeff Kent? While he was a Met? From August 1992, when he was not yet any kind of name outside Toronto, to July 1996, when it seemed fait accompli that he’d be dealt to somebody somewhere sometime soon (he’d been moved off second base and marooned at third because Jose Vizcaino had been bumped from short and transferred to second in the interest of making room for Rey Ordoñez’s magic glove), there was no inkling that Jeff Kent of the New York Mets would become Jeff Kent of the Hall of Fame. Not even in National League Player of the Week mode, as delicious a week as that was. Not even when the 1995 Mets finished on an unforeseen upswing, going 34-18 and raising unreasonable hopes for 1996. Late ’95 was a whale of a time to be a hopeful Mets fan. Everybody was youthful, everybody was doing something promising.

Unfortunately, that was also the year when a meeting among Mets fans was called and it was decided we were going to mostly boo Jeff Kent as long as he was around (and really let him hear it should he ever go). His pre-strike gleam wore off. The better-angels side of his nature — I seem to recall a “Kent’s Kids” sign over the Picnic Area seats, and he was a spokesman for the No Small Affair organization that served disadvantaged youngsters — didn’t cut much ice against a personality that didn’t mesh with the Hootie & the Blowfish vibe the latest youth movement evinced. “How ’bout them baby Mets?” John Franco was heard to shout with a little love and some tenderness after one particularly uplifting triumph. Those were the Mets of Pulse and Izzy and Rico and Huskey and rookie Fonzie. Kent was among them as well if not exactly of them.

The young Mets played beautifully over the last two months of 1995. Yet amid the proto-OMG emotion of that late summer, Jeff Kent, 27, seemed atonal in relation to the whole “Hold My Hand” arrangement. As that season finished, Marty Noble described Kent’s status for the future as “unclear,” citing “his failure to drive in runs [as] a critical factor in the team’s poor early performance. He made a comeback, but it has been gradual and rarely conspicuous. And the club is quite aware that his square-peg personality grates on his teammates.”

Fair or not, the last couple of years of Kent as a Met and Met mope (the Jeff Can’t phase) set the stage for the reception we’d give him as an opponent, including two postseason interactions — in 2000 and 2006 — when his presence as a losing Giant and then losing Dodger landed as a fringe benefit within Met Division Series victories.

But there he is. Hall of Famer Jeff Kent, no matter what we were thinking when he was New York Met Jeff Kent. For his part, I get the idea that Kent stopped thinking about us a long time ago. He was gracious enough to join Jay Horwitz on the alumni director’s podcast shortly before the Contemporary Era Committee voted, and he mostly pleaded amnesia as regarded his Met years, save for liking Jay and appreciating Dallas Green.

Y’know what, though? Good for that mope of a Met making the Hall. I love in 2026 that the dreadful 1993 Mets were studded by two Hall of Famers, Murray and Kent. There was nothing that felt immortal about attending sixteen games at Shea that season, but one did come away from the whole experience feeling baseball-bulletproof. If this kind of year can’t kill me, nothing can — and I got to see two Hall of Famers over and over!

July 29, 1996: CARLOS BAERGA traded by the Cleveland Indians with Alvaro Espinoza to the New York Mets for Jeff Kent and Jose Vizcaino.

Murray was gone before 1994, off to Cleveland to have the kind of effect — leading a younger team toward the playoffs — he never had in Flushing. Kent carried the Cooperstown banner forward on his own at Shea. Not that it was visible in real time, but we now know it was there, clear to the day he and Vizcaino were traded to Cleveland for former All-Star Carlos Baerga and utilityman Alvaro Espinoza (missing the Baltimore-boomeranged Murray by about a week), a classic trade that didn’t seem to help anybody in the short term. The Indians went to the playoffs with Kent and Vizcaino, but they were going, regardless. Then they got rid of their ex-Mets and kept winning. Cleveland was a way station for more than one young or young-ish Met who’d pick up steam elsewhere. Jeromy Burnitz as a Tribesman in 1995 didn’t contribute much to their successful pennant push. He had to be shipped to Milwaukee to attain the stardom Dallas Green was too impatient to cultivate.

It took a second trade, to San Francisco (again with Vizcaino), to thrust Kent into star territory. In San Francisco, starting with the ’97 season, Kent would hit behind Barry Bonds, see streams of good pitches, hone his power stroke, and begin printing his calling card: most career home runs by a player who primarily played second base, 351 of his 377 total. Not Hornsby. Not Morgan. Not Sandberg. Kent…yeah that Kent. Turns out his 1993 was the start of something big. How big couldn’t be known then. In 2000, he won the National League MVP award for which Piazza was frontrunner deep into summer. Mike caught every day and it caught up with him. Bonds put up Bonds numbers, but that was to be expected. Kent produced stratospheric statistics for a middle infielder: 33 homers, 125 RBIs, a .334 batting average. The Giants finished first. So did he. Between 1997 and 2005, Jeff earned two Silver Sluggers, was named to five All-Star teams, and received MVP votes six separate times.

You may or may not have begun to connect Kent with the Hall of Fame as his career enjoyed its highest heights, bulging with slugging statistics as it was. A lot of sluggers had impressive statistics in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some seemed less impressive as revelations came to the fore. None attached themselves to Kent. He was the second baseman with the most home runs. After he finished up in 2008, his name tended to get mentioned in the company of those who would be crowding the ballot in 2014. Greg Maddux, Frank Thomas, and Gl@v!ne figured to be locks, and they were. Mike Mussina would creep up the ranks until winning the golden 75% of the BBWAA vote in 2019. Kent went ten years without cracking 50%. Then came the committee, which took a closer examination of his calling card. If he wasn’t the ablest defender or the friendliest teammate, he didn’t have to be. No second baseman hit more home runs.

This all followed the Kent-for-Baerga trade. Baerga gave us one solid veteran-leader year during his 1996-1998 stay, coinciding with the Mets’ ascent to contention. When Alfonzo was inducted into the club Hall of Fame in 2021, he invited Baerga to be an honored guest at the ceremony, indicating some genuine impact from the man who our Carlos B before we came to know Carlos Beltran. Contemporary accounts of the rising 1997 Mets pointed to Carlos Baerga as a clubhouse catalyst, and he definitely chipped in some big hits as the team rose from 71-91 to 88-74. This all followed the Kent-for-Baerga trade. Baerga gave us one solid veteran-leader year during his 1996-1998 stay, coinciding with the Mets’ ascent to contention. When Alfonzo was inducted into the club Hall of Fame in 2021, he invited Baerga to be an honored guest at the ceremony, indicating some genuine impact from the man who our Carlos B before we came to know Carlos Beltran. Contemporary accounts of the rising 1997 Mets pointed to Carlos Baerga as a clubhouse catalyst, and he definitely chipped in some big hits as the team rose from 71-91 to 88-74.

But with massive hindsight, it’s hard to say we won the second Jeff Kent trade, just as it’s glibly easy to say we won the first one. You trade for a future Hall of Famer before it is sensed he is a future Hall of Famer, you’re entitled to call it a win. You trade one away? Well, that’s the business of baseball. Baerga, who had been really good for Cleveland until he wasn’t, lingered long enough in the bigs to play for the 2005 Washington Nationals. Cone had enough pitches in his right arm to return to the 2003 Mets following some notable successes with Toronto (World Series ring), Kansas City (Cy Young Award), and some other New York team (whatever). Yet they’re not Hall of Famers. Maybe Cone deserved a closer look, but to date he hasn’t. Hell, George Foster hit 348 home runs in an era when that was a ton, and received only negligible Hall support in four elections — and he had his own comic book!

Let’s leave George out of it for the moment. Let’s consider Hearn for Cone for Kent for Baerga, plus Cone coming back to finish up in orange and blue, and Hearn persevering through health issues to make all the 1986 reunions, and whatever it was Baerga taught Fonzie that shaped Edgardo into the most important non-Piazza player we had during the Bobby V years. Let’s say we won the Jeff Kent Trades over and over, even if Kent didn’t make a semblance of a case for immortality until he made it to San Francisco. Let’s leave George out of it for the moment. Let’s consider Hearn for Cone for Kent for Baerga, plus Cone coming back to finish up in orange and blue, and Hearn persevering through health issues to make all the 1986 reunions, and whatever it was Baerga taught Fonzie that shaped Edgardo into the most important non-Piazza player we had during the Bobby V years. Let’s say we won the Jeff Kent Trades over and over, even if Kent didn’t make a semblance of a case for immortality until he made it to San Francisco.

Had he stayed a Met, you imagine the bat would have found a place in that late ’90s lineup, but once we had Fonzie at second and Robin at third, did you miss Jeff Kent whatsoever? For that matter, did you miss Nolan Ryan when we were running Seaver, Matlack, and Koosman to the mound every week? Besides on principle? Transactions are nuanced. They can look bad in the moment and worse with perspective, but not totally disastrous in the scheme of things.

Thus, I am comfortable to declare that it really happened. We traded somebody at the top of his game for a veritable unknown, and the veritable unknown went on to a Hall of Fame career after the Mets got him. Also after he left the Mets. A lot more after he left the Mets than when he was with the Mets. Honestly, an accurate assessment of trading for and away Jeff Kent requires immense nuance. In a comic book universe, however, we can position the facts as we see fit to create the most crowd-pleasing storyline we can.

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2025 1:29 am “It’s great to be young and a New York Giant,” second baseman Larry Doyle declared to Damon Runyon in 1911, the year Doyle turned 25, the season the Giants won the first of three consecutive National League pennants. More than a century later, you could hear an echo of Laughing Larry in the earnest sentiments Jonah Tong expressed into Michelle Margaux’s SNY microphone:

“I love being a Met. It’s truly one of the coolest things I’ve ever done in my entire life.”

It’s great to be young and a National Leaguer in New York… Tong, at the time, was 22 and dressed as a Christmas elf, helping out at the annual holiday party the New York Mets host for area kids. Perhaps that, too, is truly one of the coolest things he’s done in his entire life. Ballplayers get more done before they’re 23 than a lot of us do before we turn 63, which, incidentally, is what I’m doing today.

…whatever the uniform. Young Jonah spoke his truth in late 2025, following what we’ll call his first rookie season. He didn’t throw enough innings to use up his freshman eligibility, so he’ll get to be a rookie again in 2026. So will his fellow elves/phenoms Nolan McLean and Brandon Sproat. Sproat and Tong showed flashes of potential, maybe glimpses of brilliance as they answered an unexpected call to the majors. McLean landed ahead of them, chronologically and developmentally, looking like a full-grown ace for the bulk of his 48 frames in the bigs. Fifty would have made him a sophomore next year. We get to get excited about his and his prospective rotationmates’ breaking through all over again in a few months.

McLean, Sproat, and Tong — Generation MST3K to me — couldn’t do enough in their initial MLB go-round after responding to the Mets’ SOS to keep the team from being AWOL during the NLWCS and any further postseason alphabet soup action. Yeah, as if it was their fault. The sneak peek they gave us of their evident talent and gestating poise was sufficient vis-à-vis our anticipation of getting acquainted with them. The Mets thought enough of the trio’s sample size to have had them support Clay Holmes when Holmes dressed up as Santa Claus.

I should have learned, en route to turning 63, not to make assumptions based on past experience, but I can’t help but think introducing 32-year-old Clay Holmes into a rumination on youthful Nolan McLean, Brandon Sproat, and Jonah Tong will someday resonate like remembering that when the Mets had Ron Darling, Walt Terrell, and Dwight Gooden ready to go in 1984 (with Sid Fernandez waiting in the wings), a soon-to-be-released Mike Torrez was their Opening Day starter. Then again, Clay Holmes was our Opening Day starter last year, and pitched pretty well the whole season, give or take some dips. The whole team took some dips, which explains why quite a few Met veterans who could have donned the Santa suit were no longer available for Citi Field events this December.

We love old players when we have come to terms with their careers. Presently, we don’t have any of those kinds of sages under contract, at least not any we know well. We love young players when we are able to imagine their careers — like we do with these kid pitchers and like we have lately with a few position players (Alvarez, Baty, Vientos) currently approaching their respective make-or-break junctures. The players who have ceased being young but are not yet old require some discernment. The Mets discerned they’d be better off going forward without four key players who’d reached their early thirties. That’s baseball middle-age. The ticking of the actuarial clock may not be precisely why Brandon Nimmo, Edwin Diaz, Pete Alonso, and Jeff McNeil weren’t dropping by Mets-run holiday parties in 2025’s waning weeks, but they were here for a long time, and now they’re not.

Get ready, ’cause here they come (again). Here now and for the foreseeable future (which comes with the caveat that you never know what lies ahead) are McLean, 24; Sproat, 25; and Tong, 22. At the moment, we are Dorothy Boyd to their Jerry Maguire.

We love them!

We love them for the Mets we want them to be.

We love them for the Mets they almost are.

With the Mets idle since the end of September, I’ve occupied myself watching the Giants mostly lose football games and the Nets beginning to occasionally win basketball games. The Giants were effectively eliminated from playoff contention that October Sunday they converted a 26-8 fourth quarter lead at Denver into a 33-32 loss. The Nets commenced their season at 1-11, pretty much torpedoing any thoughts that April will deal me any roundball/hardball conflicts. Yet Brooklyn has gone 9-9 in their past eighteen, buoyed by a couple of capable rookies, Egor Dëmin and Danny Wolf. And the Giants finally won a game the other day, which doesn’t help their draft position, but added to the sense that their first-year quarterback Jaxson Dart, who’s the reason (besides ingrained habit) that I keep tuning in, won’t need replacing under center. Dart can be a real QB. Dëmin and Wolf and the other youngsters among the Flatbush 5 first-round draft class are making the Nets, until further notice, into a real team. It’s real beautiful to watch kids grow up as pros.

McLean, Sproat, and Tong started getting the hang of that in 2025. It was only the beginning of what we want to feel forever, forever being a malleable concept to a Mets fan who’s been around, a Mets fan who keeps coming back for the raising of hopes regardless of prior results. In 2025, I kept waiting for the Mets to sweep me off my feet, but apparently they lacked upper-body strength. Still, there was something about those arms. Those arms (and ingrained habit) will keep me coming back.

I may be old enough to know better than to fall in love with the next fledgling youth movement, but I’m also old enough to know it’s not much fun getting older without a few Met futures to anticipate. It’s truly one of the coolest things I’ve ever done in my entire life…which must be why I keep doing it.

by Greg Prince on 26 December 2025 8:06 pm Previously on Flashback Friday…

A little piece of me is always watching the Mets in 1970.

Mostly I was enchanted with the possibility that the Mets would win the World Series in 1975.

I was in love with the 1980 Mets. They weren’t the first Mets team I was ever hung up on, but I think, given where I was in life, that they were my first love.

I gave myself over to baseball and the Mets in 1985 in a way I never had before.

If there was ever going to be a year when I might have discarded baseball and pleaded no lo contendre to the charge that I allowed myself to be distracted from the Mets by overwhelming matters of substance, 1990 would have been that year. But it wasn’t and I didn’t. Amid a seismic personal shift that separated what came before from what came after, I was just doing what I’d always been doing. I rooted for the Mets like it was life and death. I didn’t know how not to.

In 1995, I was determined to spend as much time at Shea as was humanly possible.

It was the Year 2000, Y2K. Actually, it wasn’t any different from the 1900s, at least not the last few of them. Since 1997, the Bobby Valentine Mets had become my cause, my concern, my reason for being. Even more, I mean. If I had to rate the intensity of my baseball-commitment on a scale from 5 to 10 (let’s face it, it was never going to dip into low single-digits), these were the 9-10 years. The needle never saw 8.

For all the sporadic delight I’ve derived from the Mets since 1969, I don’t think I’ve ever been quite as personally gratified by a season as I’ve been by 2005.

Make no mistake about it: we lived in 2010. Of course we did. We live in every season as if it’s our permanent residence. We inhabit them fully. Each one is the most important season of our lives while it is in progress. Across the entirety of 2010, I sat at this very spot and, in concert with my blogging partner sitting in whatever spot he was in, set in type that entire April-to-October effort. It mattered to me. It mattered to you. Then it mattered no more. Weird how that happens.

There’s nothing better than the year that Feels Different, and before we had a chance to feel anything else, 2015 felt different.

And now: Flashback Friday.

***

Had Major League Baseball not presented its farcical version of a season in 2020 — no games until late July; 60 games in all; zero fans in attendance; everything a little to a lot off — Pete Alonso’s career home run total would have sat at 248 when he left the Mets for the Orioles this month, meaning Darryl Strawberry would still hold the franchise record at 252. That is unless Pete would have been moved at the end of 2025 to stay a Met a little longer for history’s sake, or the Polar Bear had powered up five more times than he actually did in the five seasons that followed the one that theoretically wasn’t played, one I almost wish hadn’t been played.

But that’s all hypothetical. Sort of like “imagine MLB needing to lop more than 100 games off its schedule and conducting its on-field exercises in front of nothing but empty seats and cardboard cutouts, altering its rules along the way, all for reasons that ostensibly had nothing to do with baseball.” Before 2020, I don’t know why anybody would have imagined such a hypothetical. By March of that year, our imaginations were becoming overwhelmed.

What a strange year it was five years ago, mostly outside the realm with which we concern ourselves here, but within the walls of Metsopotamia as well. COVID-19 crept into our collective consciousness in January. Whatever it was, it was said to be dangerous to everybody. By March, it was unstoppable. It stopped Spring Training and then the season’s beginning. It stopped just about everything, so why should baseball have been any different? It surely stopped the sense of momentum the Mets carried over from the end of the previous decade. The 2019 Mets made themselves memorable by finishing strong, clear through to Dom Smith’s rousing final swing on the season’s final day that nurtured optimism for the near future. The offseason leading into 2020 was brightened by the story of how those young, spunky Mets gathered for milk and cookies and hitting talk on the road after games. They were the Cookie Club, and how could you not be optimistic about that? Alas, the “Summer Camp” that prefaced the impending ad hoc season brought a bittersweet update from Jeff McNeil:

“We may have to do some Zoom calls and order in.”

No, it wouldn’t be the same. Once the 2020 season didn’t start on time, and especially once the 2020 seasonette got going, memories of 2019 existed on an island, disconnected from a next step. Yet it was 2020 that was bound to live in true isolation, sheltering in place from what came before and what might come after. Members of Mets teams that earned postseason berths in 2015 and 2016 played alongside members of Mets teams that would go to the playoffs in 2022 and 2024. None of that experience with or capability of success rubbed off on the unit that called itself the 2020 Mets. To be fair, the 2020 Mets didn’t have much runway. The 2019 Mets were past 90 games before they began to coalesce into lovability. The 2020 Mets had only 60 games total. To be just as fair, all they had to be, essentially, was the eighth-best team in their league to be granted a World Series Tournament bid, and they couldn’t manage that much. The Cookie Club and everything else that felt promising prior to 2020 simply crumbled.

It seemed unseemly to complain to much about the Mets’ indifferent results when the world was unsettled by weightier issues. Not that we didn’t complain. With a pandemic in progress, we had not much else to do in 2020. Complaining bitterly and watching empty-stadium baseball became the newest national pastimes. Complaints — legitimate and concocted — were everywhere. Mets baseball was on TV and radio if you wanted something else to get annoyed by.

Remember that most obscure Mets season? It’s OK if you don’t. It was destined for instant obscurity from its delayed outset, and did nothing to divert from its path to nowhere while it went about its abbreviated business. On July 24, 2020, the Mets commenced their condensed NL East/AL East-only schedule with a victory over the Braves. Yoenis Cespedes, anachronistically sharing a box score with Pete Alonso, homered to give the Mets a 1-0 win. Soon Cespedes would decide he preferred to not court the coronavirus and opted out of further baseball. That was something players could do in what the commercials called These Challenging Times. For a couple of days, Cespedes ceased to be the revered slugger from the 2015 pennant surge and became the guy who ghosted on his teammates and, by extension, us. I assume he is more widely remembered now for his heroic entrance onto our stage than his murky exit from it, but in the moment, he made for an easy object of online Mets fan scorn.

Not that Yo would have heard any boos. The only noise at ballparks was piped in, intended to add a lifelike quality to an otherwise desolate atmosphere. Cespedes, when he hit that Opening Day home run, was serving as DH at Citi Field. That was new in 2020. Player health was enough of a potential red flag to let MLB shove the designated hitter into the National League, lest pitchers drop like flies on the basepaths. Same for this new scourge that became known as the ghost runner. You get to extra innings, you put a runner on second base, the maker of the last out from the last inning, specifically. Was it baseball? It was now. Same as doubleheaders whose games were each seven innings…unless they went to extras…meaning the eighth and maybe the ninth.

It was all very bizarre and not particularly welcome. Had the Mets made more of it, it might look different a half-decade later, but the Mets made nothing of it, going 26-34 and finishing in a fourth-place tie. They stayed in mathematical contention to the final weekend mostly because it was almost impossible to not last nearly 60 games. They did their best to opt out of the “pennant race,” but hung in just the same.

The Mets who weren’t a part of better teams before or after 2020 were destined for their own individual pervading obscurity, at least as we define it. Some players who had representative careers just sort of passed through Flushing. That happens every season, but this was the worst possible season to do it if being remembered as a Met was ever your goal. I could tick off close to a dozen names that would draw blank expressions from Mets fans who probably watched the games in which those names were sewn onto the back of Mets uniforms. Forty-seven different players played for the Mets across those 60 games. There was little time for introductions let alone impressions. Of those who showed up at Citi for the first time, maybe two Mets became known as Mets. One was, by 2025, the last of the new-for-2020 Mets, David Peterson. The other was another promising rookie, Andrés Giménez, and he lives on in the Mets consciousness as the primary trade piece exchanged for Francisco Lindor.

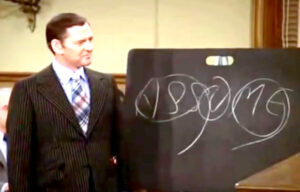

That trade, which also sent Amed Rosario to Cleveland, happened in 2021, by which time Steve Cohen had taken over ownership of the club. A different owner employed a different general manager than was on the job in 2020 (there’d be a lot of that). The manager who nominally led the Mets in 2020, Luis Rojas, wouldn’t make it to 2022, though he wasn’t supposed to manage the Mets in 2020 to begin with. Carlos Beltran was Brodie Van Wagenen’s unorthodox hire post-Mickey Callaway, but that choice imploded when it was discovered Beltran played a key role in the Houston Astros’ unorthodox world championship strategy of 2017. Van Wagenen, it will be recalled, was hired by Jeff Wilpon, who would have nothing to do with the Mets after 2020, same as Van Wagenen.

Almost everybody who was here would be gone soon enough. Even more than usual. That was how 2020 and our scant developing memories of it operated. A few moments stand out in my mind, and I could detail them, yet despite my self-imposed obligation to flash back to it in the waning days of 2025 (I have a longstanding thing about Mets seasons that end in “0” and “5”), I don’t see the point in diving a whole lot deeper.