The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2025 2:49 pm If you were curious as to what a 2025 New York Mets lineup that doesn’t feature Juan Soto would have looked like, you got a glimpse Wednesday night at Citi Field. Carlos Mendoza rested his right fielder, the fellow who’s batted second every game since Opening Day, the guy who — whether he’s raking or not — changes the complexion of the top of the Met order by his mere presence. Just a night off, the manager said, followed by a teamwide off day, followed by the road portion of the Subway Series, where Juan will be greeted loudly if not universally warmly. One full game sat approximately every quarter-of-a-season seems reasonable. Only Felix Millan in 1975 and Pete Alonso in 2024 never missed a Mets game. Heck, even the immortal Chris Majkowski, who produced 5,010 consecutive broadcasts from August 1993 to just the other day, is briefly sidelined from the Audacy Mets radio booth.

Sitting Soto didn’t seem helpful to the immediate goal of sweeping the Pirates, but in a long season, everybody merits a breather and, more importantly, everybody who usually sits needs to play now and then. Plus, if we can be a bit haughty about it, you shouldn’t have to deploy your entire “A” team to beat the Buccos. Pittsburgh entered Wednesday’s action at 14-29, on their second manager of the year. We were 28-15, sporting the best record in all of baseball, tied with the Tigers and a half-game better than the Dodgers. Most relevantly, we were three up on the second-place Phillies in our division. If you were ever tempted to gently lift a pinky toe from the gas pedal, this was a prime opportunity.

Jose Azocar played in Soto’s stead. Jose Azocar almost never plays, unless it’s to run for a less speedy Met. I don’t think this upfront substitution was entirely the reason the Mets didn’t win one game on one rainy night in May, but I wouldn’t do this again if I could help it. Nothing against Azocar. Good teams need pinch-runners, and pinch-runners oughta test the rest of their skill sets against live competition so they stay fresh for when called on to be complete players. Someday, you might need Azocar to do something besides stretch his legs.

Maybe do it in left or center field next time, though.

Wednesday, without Juan, the Mets lost, 4-0. It wasn’t as simple as going Sotoless, nor should the defeat be directly attributed to Azocar. Jose trapped rather than caught a ball in right; got picked off after drawing a walk; and flied out with the bases loaded to end the only genuine Met threat of the night, but he’s not the one who made the ball slicker than preferred for Clay Holmes, and he’s not the one who may have squeezed Holmes on balls and strikes, and he’s not the only one who didn’t drive in any Mets.

It was an uncommonly blah 2025 Mets game. Sitting out any further dwelling on it seems the wise move.

by Greg Prince on 14 May 2025 2:18 pm The 1986 Mets were so good that they couldn’t be stopped by a ball landing in a glove; the ball staying in the glove; and the glove and the ball being tossed as one to record a putout against them. All of that happened when Keith Hernandez grounded a ball back to Giants pitcher Terry Mulholland. Mulholland, then a rookie, simply could not extract that little white devil from his brown leather. Thinking fast, he took the whole package and threw to it first baseman Bob Brenly. It was legal. It was effective. Hernandez was out.

Mulholland: “I tried three times to get the ball out of my glove. Finally, in desperation, I just threw it.”

Hernandez: “That was a first for me.”

Davey Johnson added that he thought about arguing the call with first base ump Ed Montague, “but I didn’t know what to argue about. I figured the play was funny enough without me arguing.”

We could laugh about it after it happened, at Shea Stadium, on September 3, 1986, because a) the Mets were already ahead of the Giants when the play took place (up 2-0 in the third); b) the Mets added a run in the very inning the play took place; c) the Mets went on to win the game by a score of 4-2; and d) the Mets were in first place by twenty games. Baseball bloopers in which your team is the one getting blooped can be amusing when they don’t hurt whatsoever.

The 2025 Mets are good enough right now that they weren’t stopped Tuesday night at Citi Field by a ball whooshing through a glove. The ball was hit by an opponent. The glove belonged to one of their own players. The slo-mo replay confirmed it was worse, or at least more embarrassing, than it appeared. It extended an inning that should have been over, led to a starting pitcher who deserved better departing before he could finish the job at hand, and set up a run that turned a Met lead into a Met-Pirate tie.

Yet it didn’t stop them from winning. Its This Week in Baseball worthiness would probably tickle our fancy if the glove had been attached to a fielder on any other team. It was less hilarious that it happened to Mark Vientos.

Ah, Vietnos. Hard as he works to tame the position made infamous by “79 Men on Third” (the count has since reached 191), he’s in there for his bat to begin with. It’s quite often a helluva bat. His defense, however, had already taken one ding in this game — his chest, specifically, when a hard grounder banged off it and into left. Hot shot, damp night, weird double; nothing is declared an error, anymore. That was in the third inning. Kodai Senga got out of it. We were up, 1-0, thanks to Juan Soto (single; steal) and Brandon Nimmo (double) in the first. It would be a bruise for Mark and hardly a black mark against anybody in the course of an evening let alone a season. Hell, he got an assist on the play that ended the inning two batters later, handling a grounder that did not assault him so much.

Vientos wouldn’t be so lucky in the sixth when he encountered something else that sizzled. This ground ball, struck by Jared Triolo, with Alexander Carnario on first and two out, was ripe for backhanding. Observed in real time, it looked like it ticked off Mark’s glove. Several balls have been ticking off several gloves in this series. Just one of those weeks, perhaps.

But, no, this was beyond an ordinary oopsie. What the ball actually did was scoot directly through the webbing of Vientos’s eyecatchingly colorful leather. Seriously, it is a very attractive piece of fielding equipment the man models, replete with robin’s egg blue base and pop-art bursts (“POW!” “BAM!”) that might have made Pittsburgh’s own Andy Warhol proud. It certainly lives up to the proprietor’s nickname inscribed on its back: Swaggy V.

Swagginess it does have. The webbing was a different story. Yet, as slow-motion replay indicated, it had a veritable hole in it, the result of loose webbing. You can’t play third base with a glove like that on your left hand, no matter how gorgeous. You can try, but the evidence indicates it isn’t a good idea. Triolo chased Canario to third with what turned into a double.

The glove that could be seen through had done its damage. Senga should have been out of the inning, but was instead removed after 102 pitches with runners on second and third. To that juncture, the ghost-forker had nursed a 1-0 lead through 102 pitches. Two walks from his successor, Reed Garrett, proceeded to load the bases and then tie the game. The longtime baseball watcher’s inclination was empathy for the starting pitcher, but Senga’s instinct was to pat Vientos on the back as he departed the mound.

Coincidentally, David Wright, the franchise’s premier third baseman, happened to be on the premises Tuesday night, and before the game he was asked about the emerging dynamic between Vientos, who earned third base from the way he swung his stick last year, and Brett Baty, who’s earning a second look by dint of his own offensive upsurge of his late. Of course David, who has only good things to say about everybody, cheered them both on: “I know Mark’s off to kind of a slow start, but Brett’s picked him up. And if Brett gets in a little rut, Mark will be right there to pick him up.”

The Captain knows from picking up. Baty, who was playing second, batted in the seventh and made sure we could mostly forget about the adventures of the glove of Swaggy V by lining an opposite-field homer to torpedo Pirate starter Mitch Keller. It clanged off the iron fence that fronts the party area, ensuring the rainy night wouldn’t feel remotely funereal. The game ended with Baty moved over to third, Luisangel Acuña (who’s recently dipped his toe into the ever-roiling waters of third base) at second, and Vientos on the bench. Mark’s glove’s webbing had been tightened by clubhouse personnel following the sixth, but now it and he were left to watch Acuña make a nifty play on the final ground ball Edwin Diaz threw to ensure a 2-1 win, exemplary defense sealing all leaks and forgiving all residual sins.

After Brett exploded at the plate over the weekend, Mark — whose own power exploits from last October remain fresh in the mind’s eye — was asked if he’d be willing to become more of a designated hitter if it meant inserting Baty’s hot bat in the lineup. Baty’s an adequate second baseman, but third was always what he was supposed to play. And Acuña’s clearly a superb second baseman on the rise, somebody whose glove you really want to see out there most innings. Mark’s answer was succinct.

“Absolutely.”

That subject matter will likely intensify as conversational fodder after Baty’s long and timely hit became the main focus of cheerful postgame chatter Tuesday night. Carlos Mendoza saw a former prospect who had teetered on the edge of Met extinction becoming a potential fixture in Flushing. “Every player’s different,” the manager observed. “For Baty, I’m just finally glad that he’s settling in.” Senga, through his interpreter, expressed delight at what he saw after exiting, especially since Brett is on his side: “If he was an opposing hitter, I think any pitcher would not like to face him at this point.” Brett himself didn’t want to delve too deeply into his hot streak. “I’ve always thought I’m capable of doing whatever I want to accomplish in this game,” the slugger of the moment philosophized. “I’m just having some success right now, and it’s nice.”

Within the realm of the Bill Gallo cartoon universe, we had ourselves a hero and didn’t need to fit any first-place Met for goat horns. Still, it was difficult to forget the image of the ball that zipped through Vientos’s glove. From his vantage point, Mendoza said, “it happened so fast, I didn’t know what happened. Somebody told me it went through the webbing, and I was like, ‘Man, tough break there.’”

Make sure the webbing’s good and fixed, and maybe we can laugh about it in, say, six months.

by Jason Fry on 12 May 2025 11:50 pm The Mets won a misbegotten mess of a game against the Pirates Monday night, a contest simultaneously wonderful and awful, with eerily parallel mistakes ahead of a Mets closing kick that left you asking, “Wasn’t there an easier way to get here?”

Nothing seemed all that stange in the early innings, as David Peterson (excellent) dueled Paul Skenes (not otherworldly but also excellent) to a near-draw. Skenes surrendered one run on exchange-places doubles by Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil; Peterson surrendered one on a solo shot by Isiah Kiner-Falefa and another when Jared Triolo scored off Jose Butto, with the run going on Peterson’s account because he was the guy who’d walked him.

Triolo’s seventh-inning trip around the bases was a strange one: walk, steal, advance on a disengagement violation (AKA Butto not getting him on a third pickoff attempt), score on a fielder’s choice. But at least he came all the way around: In the fifth, Triolo was on second with two outs when Ke’Bryan Hayes hit a grounder that glanced off Brett Baty‘s glove and spun its way across the outfield grass, one of those hideous little plays that kills us at Soilmaster Stadium every other season. Triolo, though, came a little ways around third, hesitated and allowed the Mets to regroup, then was stranded a batter later.

The bottom of the seventh was a weird mirror image. Pirates reliever Caleb Ferguson hit pinch-hitter Tyrone Taylor (who’s always in the middle of everything) in the foot, sending him to first. Taylor stole second, arriving just ahead of a strong throw from Henry Davis, then took third on an infield single from Luisangel Acuna, with Acuna’s margin between safe and out at first maybe a tenth of an inch.

Francisco Lindor struck out, but Juan Soto hit a strange cue-shot grounder to first to bring home Taylor with the tying run. Next came Pete Alonso, who hit a grounder off the glove of Hayes that wound up spinning on the outfield grass. Yes, the same Hayes who’d hit the grounder off fellow third baseman Baty’s glove. Like Triolo, Acuna hesitated briefly after rounding third, but was quickly reminded of his scampering duties by Mike Sarbaugh and hurried homeward, with Nimmo lying on his belly as a visual cue to slide.

Acuna slid. If Davis had taken the throw on the third-base side of the plate he’d have had Acuna dead to rights, but he ceded the plate. If Acuna had slid straight into the plate he’d have been obviously safe, but he slid to the right of it, reaching for it with his fingertips instead. Acuna’s margin between safe and out at the plate? Pretty much the same as it had been at first.

The Mets had the lead and kept it when Nimmo bailed out Dedniel Nunez in the eighth, leaping above the left-field fence to take a home run away from Joey Bart. But then the ninth arrived and the game degenerated into a slapstick farce.

With Edwin Diaz having worked back-to-back games, Huascar Brazoban was tapped to secure the save. That would have been amazing when Brazoban arrived last summer, saucer-eyed and jelly-legged from Marlins PTSD; now it seemed reasonable, a testament to Brazoban’s resurrection by the coaching staff and his own hard work.

Brazoban gave up a leadoff single to March Met Alexander Canario, but coaxed a grounder from Triolo — a hot shot, but straight into Lindor’s glove as prelude to a 6-4-3 double play … except it banked off Lindor’s glove and everyone was safe. Davis bunted the runners to second and third, and Hayes hit a hot shot to Acuna, who was perfectly positioned to cut down the runner at plate and leave the Mets an out from victory … except the ball banked off Acuna’s glove, everyone was safe and the game was tied.

After a pep talk from Carlos Mendoza, which I presume was some more optimistic variation of “keep doing the thing that should be working but isn’t,” Brazoban got another grounder from Bryan Reynolds. It was against the drawn-in infield, a much more difficult chance than the two balls Met infielders had muffed, but McNeil was able to start the double play, because baseball.

In the ninth, against David Bednar, Acuna struck out trying to hit a ball to Mars and Bednar got a grounder up the middle from Lindor … which ticked off the top of second base and went through Kiner-Falefa’s legs. Soto scorched a single to right-center that sent Lindor to third, and Alonso turned in the kind of AB we wound have found miraculous in 2023 or 2024 but are now starting to take for granted. Alonso refused to expand the strike zone, worked the count to 3-1 and got a middle-middle four-seamer from Bednar that he sent into the outfield. It was obvious the moment it left the bat that it was deep enough to score Lindor and win the game; it was and it did.

It’s not often that a reliever blows the save, vultures a win and you nod and sagely declare that justice has been done. But that’s what happened. The Mets had won, and while there was probably a easier way to get there, the hard way will do.

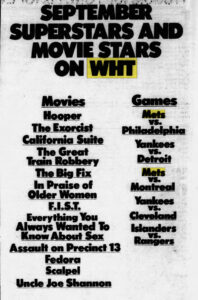

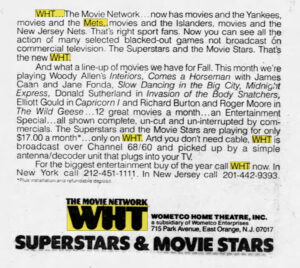

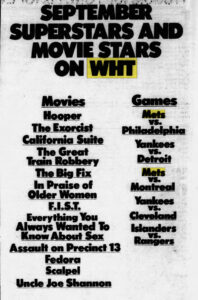

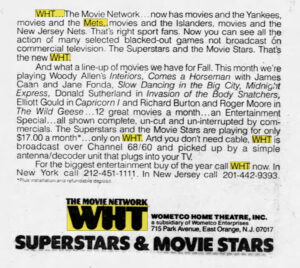

by Greg Prince on 12 May 2025 1:15 am I burrowed inside my television early Sunday afternoon, and there it was: Roku, right where I left it. I hadn’t watched it much since last summer when I installed it so I could take in a desultory Mets-Marlins affair because MLB told me it was the only way I could see it. Streaming a game via Roku reminds me of the Mets (and a few other local sports franchises) getting involved with Wometco Home Theatre in the very late 1970s. Some otherwise untelecast games were on this new thing called SportsChannel, for which you needed cable, and not everybody in the New York Metropolitan Area was sufficiently wired. But if you sprang for the monthly fee of seventeen bucks, you could get a box for Wometco, or WHT, which picked up some of those SportsChannel games along with films that had not long before been in movie houses. You turned on your TV, clicked over to UHF, dialed up to Channel 68 — more familiar as The Uncle Floyd Show’s base of operations — and there, apparently, WHT was. I say “apparently,” because we weren’t spending to unscramble the Channel 68 signal with a box. I liked the idea that the 1979 Mets were hiding somewhere behind an uncooperative vertical hold, but if a game wasn’t on Channel 9, I listened to it on WMCA.

Putting the Met in Wometco. Unless the Mets decide to give out Lee Mazzilli posters soon, I believe this will be the last time anything about this club in 2025 takes me back to 1979. That was an infamously miserable Met year. This year, except for needing modern-day Wometco to witness every pitch, seems to be the opposite. No infamy orbits these Mets, and you have to take yourself to a truly ultra high frequency to tune in any misery.

A quarter-season in, these Mets strike me as very much their own thing. They don’t remind me all that much of any of their predecessors, certainly not the enormously dreadful ones and not even the mighty successful ones. This team feels built to win without making too much of a daily whoop about it. They’re enjoying the winning they’re doing and they’re not thrown off course when the occasional loss interrupts their victorious train of thought.

Perhaps I’m projecting. I can edge into angst when runners are abandoned on base and sink into a funk after a defeat, but my psychological foundation may be as solid as it’s ever been where the Mets are concerned. I’m on a steady high, overjoyed that they’re this good while not surprised that they’re this good. How good is “this good”? Their record of 26-15 speaks for itself, but I keep coming back to eight of their losses being by one run and four others being by two runs. It’s not inconceivable that a few more big hits sprinkled about their schedule would have this team in the stratosphere rather than just first place. Maybe they’ll regret not driving in those runs when they had the chance. But I don’t think this team is going to come down with a case of the if-onlys or be about regret as it takes on its next three quarters.

Roku is only the latest example of the Mets intermittently hiding inside your television. On Sunday, on Roku, with Gary Cohen behind one mic and SNY director John DeMarsico calling the literal shots, it felt like our version of 2025 out there. It was closer than we would have liked, because what we really like is a double-digit lead in any inning. We were ahead of the Cubs, 1-0, for quite a while, because Luis Torrens is an RBI triple kind of catcher and because the pitcher he was catching (before Luis took a foul ball where even auteur DeMarsico doesn’t have a camera stationed) is an advertisement for whatever alchemy the Met Pitching Lab is churning out. Griffin Canning was his usual spotless self until Pete Crow-Armstrong launched a solo homer onto Carbonation Ridge in the top of the sixth. You can maintain regret for PC-A not being NYM five years after we drafted him, but not that’s not regret to be aimed at anything our front office has done lately. Mostly, you can raise a sparkling soft drink to a presumed fringe starter yet again giving the Mets what has become a Canning kind of outing over six innings. Crow-Armstrong’s one-run ice cube, on whatever beverage-branded plaza it landed, was all Griffin gave up.

And then we got the run right back in the bottom of the sixth, when the Mets third baseman kept doing what the Mets third baseman had been doing all weekend. Sunday the Mets third baseman was righty-swinging Mark Vientos, looking like the Mark Vientos who we previously judged was the the Mark Vientos. Lefty Brett Baty sat despite the three home runs he socked Friday and Saturday, because Carlos Mendoza deals from a deck of capable players and is determined to get everybody in and going as a given situation suggests. The Cubs threw a lefty, Matthew Boyd. Third baseman Vientos hit him 375 feet to left field.

Chicago evened the score at two in the top of the seventh off Reed Garrett, and that could have been trouble. But it wasn’t. The home eighth gave us Francisco Lindor leading off and breaking the 2-2 tie. No bloop, all blast. Lindor didn’t come through in the ninth on Saturday night. He made it his mission to compensate for that shortfall Sunday afternoon. That’s not a dreamy fan’s fanfic inference. That’s what he said after Sunday’s game. Lindor’s good enough so he can decide something like that and make it happen. The Mets have a few guys you suspect can put their minds to their bats and deliver as desired.

Pete Alonso doubled. Vientos singled him in to give the next reliever some breathing room. Jose Azocar came in to pinch-run, which imminently tickled me, because Azocar’s assignment was as stressless as imaginable once Brandon Nimmo became the third Met to homer on the day, the second to do so in the eighth. My amusement that Azocar was now a pinch-trotter was soon supplanted by a slight chill a flashback to a fairly recent event gave me. The event was from more than seven months ago, but it carries that “it feels like yesterday” quality still.

At Mets 6 Cubs 2 in the eighth on Sunday, Gary didn’t invoke the phrase he sort of used for another two-run Nimmo home run that provided the Mets a seemingly safe eighth-inning advantage, yet I heard myself utter it out loud as Brandon followed Jose around the bases:

“Brandon Nimmo puts the hammer down!”

That co-opted description originated in the top of the eighth last September 30 in Atlanta. Relistening to it a dozen times since, I notice Gary edits himself midcall, from almost saying “the hammer,” to actually saying “a hammer,” as if he knows the 6-3 lead the Mets have taken over the Braves isn’t going to be the final score. As we were about to learn, it wasn’t. The Braves stormed back to plate four off of Edwin Diaz in the bottom of that eighth before Francisco Lindor did his own storming when the Mets were up in the top of the ninth, putting us in front, 8-7, and ultimately pushing us toward the playoffs.

It’s a season later, but if I see Nimmo and Lindor each homering in the late innings like they did that quasi-sudden death Monday, I’m conditioned for confidence. I saw them do it on Sunday, in a game that was merely the 41st of 162, on some channel I forget exists when the Mets aren’t playing within its streaming confines. On May 11, 2025, I was comfortable with the notion that “the” hammer had been put down by Brandon. The 2025 Mets are their own definitive thing, and I usually respond to what they’re doing in the here and now. Yet 2024’s levitated regular-season ending — its in-the-moment conditionality notwithstanding — clearly set me up to instinctively look for the best in this current edition’s personnel. Even in Edwin, even if I reflexively ad-libbed lyrics to the melodic refrain of “Narco” after Gary’s analyst du jour Joe Girardi mentioned amid the trumpets blaring that at 6-2 in the ninth, it wasn’t a save situation.

“just end the game…just end the game…just end the game…just end the ga-a-a-a-ame!”

Diaz must have been listening, because he treated the four-run lead as something that required urgent preservation, and three quick outs later, that 6-2 lead became a 6-2 win, and this year’s particular strain of joy splashed at me and flowed through me and stayed in me. Wherever Rob Manfred insists on stashing the Mets on any given Sunday, I’m glad I can track them down. They’re too good a show to miss.

by Greg Prince on 11 May 2025 6:27 am For Cubs fans, Saturday night centered on the successful major league debut of hot pitching prospect Cade Horton. We saw for ourselves what the heat was all about, as Cade made Citi Field hay of just about every Met batter for four innings (the second through fifth) except for one, our own hot prospect of 2022, perhaps our reborn contributor for 2025.

The budding career of Brett Baty, the Mets’ No. 1 draft pick of 2019 — the one who didn’t get away between 2018’s Jarred Kelenic and 2020’s Pete Crow-Armstrong — can’t be said to have fully imploded, but his extended big league trial surely experienced a failure to launch. Brett’s enjoyed good moments here and there across the past three seasons, but they’ve been interspersed with disappointment, whether injury- or performance-related. Last year’s Opening Day third baseman went to the trouble of learning a new position, only to become the odd man out in a roster squeeze.

Rosters have a way of opening up. After Jesse Winker strained his oblique last weekend, Opening Day second baseman Baty came back from Syracuse. This weekend, he’s the starting third baseman again, at least for a couple of days. Mark Vientos, who seemed to have put a stranglehold around the eternal slippery eel of Met defensive positions with his otherworldly 2024 postseason, rode the bench Friday and DH’d Saturday, perhaps a sign that an incandescent October doesn’t necessarily carry over to the following April and May. It’s just two days in which Mark has ceded his usual assignment. But what a two-day stretch it’s been for Baty.

Friday night, Brett smacked one of four Met home runs. When four Mets homer and all of the Mets cruise to victory, one homer doesn’t necessarily stick out. Saturday night, against bulk guy Horton in the fourth inning and Cubs setup man Julian Merryweather in the eighth, Baty went noticeably deep. Two runners were on in the fourth, one was on in the eighth. Baty took Horton to right-center and Merryweather to left. There was no doubt regarding either shot’s destination. Both home runs brought the Mets close, each trimming their deficit to one. Unfortunately, no other New York batter brought much to the plate, and the Mets lost, 6-5.

One more one-run loss (we’re 8-8 in that Rorschach category) generates its own burst of frustration, but the game’s outcome can be somewhat overlooked in light of Baty demonstrating that his potential hasn’t withered away at the ripe old age of 25. No player who excels when his team has been humbled can evince excess happiness in postgame interviews, but you couldn’t miss the glint of satisfaction in Baty’s response when he told a reporter, “I like hittin’ the ball hard. I’ve been hittin’ the ball hard.” Sometimes hard hittin’ doesn’t produce base hits because opponents’ gloves can create hard luck. Sometimes hard-hit balls leave the yard a couple of times. Sometimes the player who does that hittin’ keeps on playin’. If he’s the only one hittin’, how could he be sittin’?

Every Met year leaves behind names as it goes along. By the time 2024 turned magical via the wizardry of Vientos & Co., you’d have been forgiven for forgetting that Baty was the Opening Day third baseman. This season, when Jeff McNeil healed and Luisangel Acuña emerged, a more versatile Baty became newly extraneous, demoted, and invisible. His wasn’t the only name penned in disappearing ink. A.J. Minter and Danny Young are out for the season after having been part and parcel of an effective bullpen. Hayden Senger, who made the most of an unexpected opportunity, is back in the minors because clubs in the majors rarely carry three catchers. Now and then we’ll hear an update on Winker’s oblique or Jose Siri’s fractured tibia. Those fellas were contributors to the Mets as they got going in earnest, but, as Yogi Berra might have opined, until they return, they’re not here…which is what Baty wasn’t until he suddenly was. Good teams survive the deletion of names from their everyday plans. Good teams prove they have depth. Good teams sort among viable options. Brett Baty may be turning himself into one once more.

by Jason Fry on 10 May 2025 10:06 am Hey Mets fans? Which National League teams do you hate?

The most common answer is that we hate — in the operatic sports pantomime sense of the word, you understand — the Braves and the Phillies. This is the way of the world, as those two teams are our principal antagonists in the National League East. But it’s never really resonated with me.

The Phillies are an interesting case — we’ve shared a division with them since 1969, but it’s only relatively recently that both teams have been good enough at the same time for any friction to be generated. That’s a historical quirk on which both Mets and Phillies fans can weigh in, with befuddlement on both sides; for me the Braves are of more note.

To be sure: I am not a fan of the Braves. Last year’s end-of-season showdown with them is one of the great cathartic moments of Met history, an exorcism of innumerable terrors. And it doesn’t take much to get me muttering about Chipper and Bobby Cox, or about John Rocker and T@m Fucking Gl@v!ne.

But these are adult dramas; when I was a kid the Braves were in the NL West, which never made any sense but was how baseball geography worked. Most of the time they were over there doing what they did, and you wanted to beat them when you had to (as the Mets did in the first-ever NLCS) but normally they were a problem for the Giants and/or Dodgers to solve. Hate the Braves? Whatever for?

As a kid I hated the Cardinals and the Cubs, most particularly the latter. I’d grown up on a steady diet of anti-Cubs lore: Leo the Lip, Ron Santo‘s heel-clicking, the black cat. And when I returned to the fold of Mets fandom, it was just in time to see the Cubs of Gary Matthews and Jody Davis and Rick Sutcliffe throw the ’84 Mets down off the mountain they’d not quite finished climbing.

Hating the Cubs, if you were a Mets fan, was as natural as breathing — even if newer generations of Met fans understandably found it a little odd. Weren’t they a problem for the Cardinals and/or Brewers to solve? Hate the Cubs? Whatever for?

These days, in truth, those fires are a little banked. The Mets, one may recall, beat the Cubs as badly in the 2015 NLCS as one baseball team can beat another one: The Cubs never so much as led in a single inning. (It turned out OK for them a year later.) These days you can depend on at least one wind’s-blowing-out donnybrook at Wrigley a summer and an influx of Cubs fans to Citi Field that puts your teeth on edge, but those are mere embers of a once-burning rivalry.

Still, embers can rekindle with just a little puff of breath. The Cubs marched into Citi Field (wearing impeccable road unis, by the way) Friday night to meet the Mets and a big, raucous crowd, with conditions chilly and blustery in a way that almost felt like October, and I felt something atavistic stirring in my Mets-fan soul: Warning! Danger! Intruders!

Which the Mets seemed to sense too. After Clay Holmes put down the Cubs 1-2-3, Lindor sent an 0-2 pitch from Jameson Taillon — the same Jameson Taillon the Mets never seem to square up — out to Carbonation Ridge, sending fans who’d just finished crooning “My Girl” into a renewed frenzy. (We’ll save further thoughts about Lindor and his music for another day.)

It was a welcome opening blow; pretty soon the rout was on. Brett Baty homered. So did Jeff McNeil, whom I realize is almost unrecognizable in those rare moments nothing displeases him and he can just smile. Next came Juan Soto, who annihilated a baseball so thoroughly that patrons out in the distant Citi Pavillon reached up quizzically as little squiggles of yarn and scraps of cowhide fluttered down from the heavens.

Meanwhile, Holmes looked as good as he has in a Mets uniform, muscling the Cubs aside with the exception of Kyle Tucker‘s solo shot. And some of the Cubs’ wounds were self-inflicted: Normally sure-handed Dansby Swanson gifted the Mets two runs by rushing the back end of a double play when he had time to set himself for the throw.

There was a bit of drama in the eighth, but it was all internal Mets stuff: After a debacle-ous debut in the desert, Dedniel Nunez was sent back out to not blow a five-run lead. Nunez started out well, fanning Swanson on three strikes and so reducing his season ERA below infinity. But he walked the next two Cubs and you could see his confidence ebb, and here came Tucker to the plate to try and make the game interesting when what we wanted was 15 minutes of boredom followed by overnight contentment.

Nunez’s control kept flickering on and off against Tucker, who couldn’t square him up (possibly because he had no idea where the ball was headed) but also wouldn’t go away. Until he fouled a slider straight up behind home plate. Deliverance! Francisco Alvarez made a little circle as the winds pushed the ball this way and that above his head, but you felt the fluttering in your stomach even before the ball ticked off Alvarez’s mitt to give Tucker new life.

This was remarkable cruelty even in a sport that specializes in it. But baseball is also very good at false hope: Nunez threw his best slider of the inning, one that Tucker swung through, after which Carlos Mendoza wisely went out to remove Nunez on a high note in favor of Reed Garrett. The Cub threat came to naught and a few minutes later the Mets had won.

If you’re a Cubs fan, you walked away muttering about plays not quite made by a normally capable defensive team, or about how in the world 12 of the Mets’ 13 hits came with two strikes. (The lone exception: McNeil’s first-pitch homer.) Most likely that was just the usual baseball being baseball zaniness that gets visited on some team every night … or maybe there’s something more to it.

Maybe this wasn’t a good idea. You probably know by now that Leo XIV, nee the Chicago-born Robert Francis Prevost, is not only the first American-born pope but also a baseball fan. The Cubs greeted this news with a gesture made perhaps in jest but perhaps in blithe assumption, the kind of thing that older brother teams in shared cities tend to do.

Not so fast Cubs: Even before Internet sleuths found the future pope in the crowd during Fox’s broadcast of the 2005 World Series, clad in classic White Sox regalia, his brother John had put the question of his Chicago fandom to definitive rest: “He was never, ever a Cubs fan. So I don’t know where that came from. He was always a Sox fan.”

If you’re a baseball fan, you get the significance of that added “ever” — it’s shorthand for no way in … well, yeah.

So Leo XIV is most likely the first pontiff able to wax enthusiastic about Scott Podsednik and explain in non-generalizations that yes, Jesus loves A.J. Pierzynski too. I’m not Catholic and in fact not religious at all, but I find this thoroughly unexpected development thoroughly delightful. And hey, right now the White Sox can use as many friends in high places as they could get. (Should he attend another World Series, Leo XIV will probably be easier to spot on TV.)

As for the Cubs, well, I don’t remember anything in the Bible about laying false claim to the allegiance of God’s representative on Earth, but it still doesn’t seem like a good idea. A certain number of Hail Marys might be advisable; I’m no theologian, but maybe one for each enemy two-strike hit would be a start.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2025 11:07 am On Jay Horwitz’s Amazin’ Conversations podcast this week, Jay reminisces with the SNY booth trio in this, their twentieth year on the mic. The host eventually retells the story of how he first met future color analyst Keith Hernandez…or attempted to meet him.

JAY: In June of ’83, Frank Cashen calls me. “Jay, we traded for an All-Star and MVP, but he hates New York. What are you gonna do?” I said, “Frank, I’m gonna go to Montreal airport, pick him up in the biggest white limo we can, and I’ll soften him.” So I go to the wrong gate.

KEITH: Yes, you did.

JAY: I went to the wrong gate.

KEITH: I went to baggage claim.

JAY: No Jay, no limo.

KEITH: Crickets. So I got a cab.

Moral: when somebody fails to pick you up, it stays with you.

Conversely, whether it’s someone you work with, someone you live with, or someone you hired, little in life is as satisfying as seeing someone come into view to make like Keith Hernandez in the clutch and pick you up. Watching from a nearly transcontinental distance, I know I got very excited to see several different Mets standing in what is known as scoring position get picked up in Phoenix over the course of Wednesday afternoon. For all the Mets had been doing right most of this still young season, it felt like that relatively simple task was going unfulfilled for too long, at least on this road trip.

But in the late innings of the Mets’ Chase Field finale, the picking up commenced in earnest.

Luis Torrens is standing on third in the seventh — Luisangel Acuña picks him up with a single!

Acuña is standing on second in the seventh — Jeff McNeil picks him up with a triple!

Jose Azocar is standing on second in the ninth — Francisco Lindor picks him up with a double and brings Tyrone Taylor, who’d been on first base, along for the ride! Of course he does, because Francisco is always doing something extra.

Lindor then finds his way to third — and he gets picked up by a Juan Soto sacrifice fly!

No need to get fancy when a base hit or sac fly will do. Soto had already given lifts to a pair of pitches for solo homers, so when you add together all the pulling up to the curb, opening of doors, and dropping off at the plate, you had seven Met runs, a total easily outdistancing the one the Diamondbacks managed. Snappy Met defense (featuring Torrens firing a bullet to Lindor to cut down a thieving Corbin Carroll in the first; and Taylor, Lindor, and Torrens combining on a seamless 8-6-2 putout of Eugenio Suarez in the second) compensated for some Kodai Senga wildness, en route to the ol’ Ghost Forker straightening himself out to transport six scoreless innings. Toss in three frames from the Effective Relief Committee (Members Kranick, Brazoban & Stanek presiding), and you had a six-run win and a happy flight east.

You also had the all-important tying of the now-concluded season series between the Mets and D’Backs. Three for them, three for us. This is all-important in case a playoff berth comes down to these two clubs holding identical records. Actually, there is no telling whether that’s going to be all-important this year, but it turned out to be all-important last year. Last year was last year, but these things live on in your consciousness until something more relevant replaces them. By late September, not having conceded a tiebreaking edge to this one given opponent will likely have receded to the back of our collective statistical mind. Maybe we’ll be far beyond the need to break a tie with anybody. Or we’ll be entangled with some less Snaky rival. Or — though I don’t believe this will be the case, as long as we continue to drive in runs that are begging to be driven in — the postseason for others in the highly competitive National League will be the offseason for us. Shudder at that last possibility.

At the moment, winning the last game against Arizona and splitting six overall with them is as much a pick-me-up as any RBI of an RISP.

by Jason Fry on 7 May 2025 8:09 am 9:40 pm starts are to be regarded with suspicion even when the baseball they produce goes well — surely one could be doing something more worthwhile with one’s time, starting with sleeping.

And when the baseball produced goes badly, as it did Tuesday night? Then one feels like the guy from the old gambler’s adage, looking around the table wondering who the sucker is.

The Mets played butterfingered, uninspiring baseball against the Diamondbacks, with Mark Vientos, Francisco Alvarez and Tyrone Taylor (of all people) undermining David Peterson with misplays and Zac Gallen throttling the hitters for the second time inside a week — the Mets scored their lone run on a bases-loaded walk against Gallen, failing to do further damage when Starling Marte was punched out on three pitches in a depressingly futile AB.

Perhaps the best news was what didn’t happen: Brandon Nimmo came up favoring his knee in the fourth inning and talked Carlos Mendoza into letting him stay out there, though Nimmo looked like less than himself the rest of the way. The same could be said of the rest of his teammates; look back to the D.C. series and the Mets are officially scuffling, with their ledger featuring a split and two dropped series with an afternoon rubber game ahead.

Maybe scuffling was to be expected, given the tough stretch of calendar; the Mets haven’t had an off-day since April 24 and have been ground up by injuries, travel and what may be no more than the usual statistical bumps and bruises of what we’re constantly reminded is a long season. Come to think of it, early May is usually about the time that particular lesson smacks us in the collective face. It’s a long season; few things bring that home more than a dishwater drab game in which you realize, too late, that none of the other people at the table is the sucker. Maybe I should have gone to bed, you think as your money vanishes into other people’s pockets, never to be seen again.

by Greg Prince on 6 May 2025 2:00 pm Thanks, Gare. Like you said, it’s midnight in Manhattan, and this is no time to get cute, yet as we know, every first Monday night of May marks the return of the Met Gala to Manhattan, and whenever the Mets are playing at midnight Eastern Time on that same night, the game is stopped, wherever it’s taking place, in this case Arizona, and the Mets stage their own red carpet walk. Here at Chase Field, it’s more of a Sedona Red carpet, with accents of teal and purple, a nod to former Met skipper Buck Showalter’s influence on the founding of the Diamondbacks franchise in the late ’90s.

And I have to say, Gary and Keith, that after dressing as a Viking when we were in Minnesota, and then visiting the Continent, as we sophisticates call it, during my week off, I have a new appreciation for fashion and am delighted you guys are giving me a chance to show it off.

The theme of this year’s Mobile Met Gala is Stealth Diego, a title chosen to reflect that although the Mets are playing this game in Phoenix, technically the Mountain Time Zone, it might as well be a late night in California. That’s certainly how some of our more sleepy SNY viewers are processing it. For them, it might as well be the 1954 Broadway musical, The Pajama Game, itself a show with something of a fashion motif.

First to stroll by on the carpet is current Met manager Carlos Mendoza, wearing a fresh take on the classic parochial school uniform, very much accenting plaids. This is Mendy’s nod to Mary Katherine Gallagher, the Molly Shannon “superstar!” character. The connection, we’re told, is Mendy’s recurring dugout pose with his arms folded ever tighter, his thumbs burrowing into his armpits. Mary Katherine, you’ll recall, had a bit with her thumbs as well, but I don’t think Carlos is going to do any sniffing, unless it’s of victory.

Next up, Pete Alonso, and Pete’s not surprising anybody with his white tails and top hat, very much the Polar Bear, an enormous animal with enormous statistics, enhanced most recently by what could be called a two-run “moonshot” in the fourth inning had the roof of Chase Field been open. Either way, Pete’s blast, like his tuxedo, was clearly puttin’ on the ritz.

Coming along behind Pete, in blood red, is Griffin Canning, making an ironic comment on how many Mets fans viewed Griffin as a “tomato can” to be knocked around, yet, as we see, guys, he’s the one who’s been canning batters’ hopes all year. That includes five-plus innings of one-run ball in the desert tonight.

Sporting bristle-yellow, it’s Huascar Brazoban. The idea here, guys, is Huascar whisks away potential threats when he comes into a game, and sure enough, the Mets’ most dependable middle reliever thus far this season has done it again in this game with two scoreless innings of shutdown bullpen work.

Will you look at who’s entering the scene for the first time in a year? It’s Dedniel Nuñez, about whom everything was sharp the last time we remember seeing him. The accessory that really catches your eye, Gary and Keith, is Dedniel’s walking stick. Unfortunately, Nuñez, in his first outing of 2025, seems to like his walking stick a bit too much, which we noticed in the eighth inning when he walked three consecutive Diamondbacks on full counts to load the bases. Not as sharp as Dedniel wanted to appear tonight.

You know, none of this haute couture — and you know I’m pronouncing it correctly, because I recently visited Europe — would be possible without the dedicated behind-the-scenes personnel who put it all together, the fashion world’s equivalent of our camera operators and the folks manning director John DeMarsico’s truck. Here, a vested Tyrone Taylor shows his respect, of course, for the tailors of the business, as he weaves a fantastic play in center field to keep a Diamondback rally in check. Tyrone grabs a ball off the wall, gets it back into the infield, and limits the damage, much as any skilled craftsman with a needle and thread would after a rollicking night on the town. Three runs in all score in the Arizona eighth off Nuñez and Reed Garrett, but it could have been much worse. It looked as if the sky was gonna fall in on the Mets there, but thank heaven for Tyrone Taylor…and the roof being closed.

Oh, this is an interesting fabric being put through its paces by Met closer Edwin Diaz, extra absorbent for the unnecessary angst he brings to virtually every outing. Keeping with the theme, Edwin allows the first runner he faces to reach base — it’s scored an E3, but Edwin didn’t exactly cover the bag in glory — and that runner, as almost all runners Edwin puts on do, takes off for second shortly thereafter.

This version of the Met Gala has the imprint of a corporate sponsor this year, Pillsbury, which we see as Francisco Alvarez pays homage to the Pillsbury Doughboy in an all-white outfit topped with chef’s hat. Francisco told me before the game he was going to wear it so any baserunners tempted to steal would be intimidated by his excellent “pop time,” and sure enough, Alvarez was up with a throw as soon as Diaz’s first runner took off in the ninth. I’d say Pillsbury got its money’s worth, as the image the catcher presents is certainly “Poppin’ Fresh”.

Style is no stranger to the area around second base when Francisco Lindor moves over from shortstop to take a throw from either Alvarez or Luis Torrens. Tonight, guys, Lindor makes an incredible grab of his fellow Francisco’s throw and burnishes it with an improbable tag to record the first out of the ninth inning. MLB is so impressed, they’re gonna look at it again in Manhattan after midnight, and, yup, it’s definitely an out. Appropriate that Lindor’s outfit includes a cape, as he is, per usual, a superhero for these Mets. He put the Mets well ahead in the seventh with a three-run homer, and now he has saved them in a nick of time with very fancy defense in the ninth. Diaz fomenting unnecessary angst and Mendoza’s tight embrace of his own upper torso are no match for the super and superb skills of Lindor, a player who always models excellence on the baseball diamond.

Guys, some of what could go wrong did go wrong here at Chase Field tonight, but this Met game indeed turned into a Met Gala all its own, with the Mets topping the Diamondbacks, 5-4, in this, the franchise’s 10,000th regular-season contest played to a decision. The Mets’ all-time record is now 4,839 wins and 5,161 losses, along with eight ties, the last of them coming in 1981.

Hopefully our viewers back home thought this milestone game and accompanying fashion show was worth staying awake through on a late Monday night turned Tuesday morning. Back to you, Gare.

by Jason Fry on 5 May 2025 1:15 am We’ve all heard Keith Hernandez say it, that common word that a California accent (or maybe it’s just Keith being Keith) strips of one familiar consonant. And Lord knows we felt it on a long Sunday that wound up for naught.

The Mets took walks. and the Mets pounded balls all over Busch Stadium against a Cardinals team they’d manhandled to the tune of nine straight wins. But not Sunday — nope, on Sunday they wound up a run in arrears in the afternoon, and then again in the evening.

The first game was more interesting than the second, as it brought the at least moderately heralded debut of Blade Tidwell, who looks about nine years old, with a funny way of repositioning his feet on the rubber that makes it look like he’s sliding sideways along a track built into the mound, like one of those hockey players in an old 70s tabletop game.

Tidwell’s final line was ugly, but I thought he actually pitched pretty well: He was a mess in the first, with his fastball elevated and no location on his offspeed pitches, but that’s to be expected. After that he was better, but undone by dinks and dunks over the infield, and a couple of pitches he put more or less where he wanted them in crisis situations, only to have the Cardinals convert them. Meanwhile, Erick Fedde walked five and got hit hard, but wound up only a little damp while Tidwell got drenched.

The Mets mounted a furious comeback in the eighth against old pal Phil Maton and JoJo Romero, and loaded the bases with one out and Pete Alonso coming up. Alonso put together yet another terrific AB, and on 3-2 Romero threw Pete a slider low and away, the kind of pitch that’s sent the Polar Bear crashing through the ice in previous seasons. This time Alonso spat on it, which was good; unfortunately it caught the tiniest sliver of the plate for strike three, which was bad.

The ninth was even more horrifying: Against Ryan Helsley the Mets got a leadoff single but then saw Luis Torrens miss a hanger, Jeff McNeil hit a bolt of a line drive directly at the right fielder, and Luisangel Acuna pop out to end the game.

Buzzard’s luck, and then we all got two hours to fume about it before watching the second game, which in the early going was like watching two drunks wail away at each other in a roadhouse parking lot. Neither Tylor Megill nor Andre Pallante was any good, leaving the game tied 4-4 after three. Then the Cardinals called on Michael McGreevy, who was wonderful in his season debut, cooling down the Met offense.

That offense ran hot but also hideously inefficient: The Mets left 10 on base and once again kept rocketing balls right at people, with Juan Soto particularly unlucky in this regard. Though not quite as unlucky as the little girl in a front-row seat who wound up flattened by Nolan Arenado through the netting on a great catch in the eighth against Soto. In the aftermath Arenado looked horrified while the girl looked cosmically nonplussed, as you might if a large baseball player suddenly came out of the sky to Panini-press you into your seat. Fortunately all involved were OK, with the exception of Soto’s BABIP.

It was that kind of day. The Mets lost, then lost again, and looked supremely frustrating in doing so. Or, sorry, make that fustrating.

|

|