The Sunday after the All-Star break at Citi Field was one of those afternoons when All Is As It Should Be. Matt Harvey was punishing the Phillies. A Dwight Gooden bobblehead was nestled inside my schlep bag. What we used to call DiamondVision found a moment between highlighting Harvey strikeouts to feature the de facto guest of honor in the non-bobble flesh. A camera found Dr. K Emeritus taking in the game on the terrace of an Empire suite, no more pretentious about it than a fella sitting on the porch and watching the neighborhood kids play in the street. Our attention was directed to his whereabouts. He waved graciously. We applauded appreciatively. Some of us stood. I’m pretty sure I did.

Yes, I thought, All Is As It Should Be. The franchise that sees powerful righthanded pitching when it peers into the mirror in search of its inner beauty had two-thirds of its holiest trinity on hand. Harvey we’d been drooling over for months. He was on the mound, the only place we wanted him. Tom Seaver wasn’t around that afternoon, but he’d toed that rubber, albeit ceremonially, a mere five days earlier, so he was excused. Gooden, meanwhile, was ensconced in a place of honor, doing what he should be doing where he should be doing it.

Dwight Gooden was being our legend-in-residence. I don’t know that he can make a living at that, but if sitting, watching, rising and acknowledging the masses keeps him and his memory safe and secure, I’m all for it being a part of his and our Metscape.

One of the great, quiet victories of 2013 was the full reweaving of Dwight Gooden back into the Met tapestry. His recurring appearances in Flushing felt like the culmination of a bumpy five-year comeback trail that commenced on the most bittersweet day in Mets history — the Shea Goodbye sendoff that returned Doc to his native soil in proper garb for the first time since 1994 — and continued until you almost didn’t notice that the trail had led to an utterly unsurprising conclusion. He showed up for Shea Stadium. He showed up for his nephew Gary Sheffield. He showed up for his induction into the team Hall of Fame. He showed up for Banner Day’s revival. Eventually, he showed up for the hell of it. “Hey, Doc’s at the game tonight,” you’d now and then mention to your companion, pointing to where he was stationed and maybe at what he was doing.

Doc’s at the game. Where else would you expect him to be?

The Mets have several well-loved ambassadors who make community-minded appearances here and there, but they don’t really have somebody whose job it is to swing by and subtly remind you how great it can be to be a Mets fan (besides Matt Harvey, and he won’t be around much for the next year). They haven’t cultivated what Red Schoendienst is to the Cardinals or Don Newcombe is to the Dodgers or what Johnny Pesky was to the Red Sox — a sage without blatantly obvious portfolio whose very aura announces “Mets” when you catch sight of him. Someone who straddles celebrity and accessibility. Someone who knows the game. Someone who can talk to the players. Someone who can and will say “hi, how are ya” to the fans.

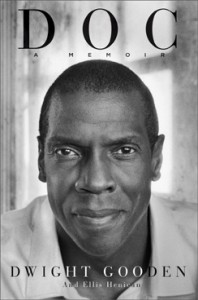

Doc Gooden stopped himself a peg shy of irrefutable immortality on the field, but he definitely visited the stratosphere. He has a story worth telling, which he did in his third and presumably final autobiography, Doc: A Memoir, the most heartfelt and genuine of the trilogy. Beyond 1999’s Heat (not to mention 1985’s Rookie) this is the one that really lets you explore the mechanics of a troubled life and makes you realize avoiding the drugs that derailed his express train to Cooperstown was never going to be easy as Just Saying No. Doc has the power to sway you from “screw him, he threw it all away” to “he didn’t really grasp what was making him throw it all away.” Where the person is now won’t permit the pitcher to reset the clock on his career — when it felt like Gooden could go 24-4 24/7 — but the important thing is that the person has a future. I’d wholeheartedly welcome his future into our presence for as long as it keeps all concerned happy and healthy.

Book promotion probably helps explain why he was around Citi Field as much as he was in 2013, but given that he lives in the area, takes his second chance at eternal Methood seriously and still revels in his craft (if you heard him analyze Harvey with Kevin Burkhardt from the stands, you heard a master dissect a prodigy), the ballpark sure seems his natural habitat. A little waving, a little coaching, a little of whatever it takes to keep the tapestry intact.

With Doc onsite as often as possible and any luck, maybe somebody else will experience an encounter like I had in 2013.

This was a few weeks before that bobblehead afternoon. It was a Friday night when the Mets were frantically pushing for the naming of Brandon Nimmo to the Futures Game roster, a selection that was subject to online voting. To generate as much excitement as possible for the event, which was going to be a Citi Field affair prior to the All-Star Game, the Mets built one of their periodic blogger nights around a conference call with Nimmo.

That’s about what it sounds like. At an appointed hour, assorted media and quasi-media were shepherded into a room with a speaker phone on the table. A number was dialed. A 20-year-old’s voice was audible on the other end. Brandon Nimmo, I allowed myself to think, spoke with the humble cadences of a young (younger?) David Wright, though that might have been just my aspirations for him talking. My notes from that call indicate that he must have worked on his interviews and learned his clichés enough to make Crash Davis proud. Either that or he’s 20 and he sincerely believes in getting better every day while letting tomorrow take care of itself.

Brandon was extremely polite and eventually excused from any more interrogation; not long after he was authorized to hang up he would indeed be on his way to the Futures Game. In the meantime, the media departed. The quasi-media — your bloggertariat, that is — remained in that room with our friendly handler who dropped, in “by the way” fashion, that when we were done shooting the breeze in here we’d be meeting with Doc Gooden.

Oh.

Sure.

If you insist.

Doc was the centerpiece of a special ticket package that night, an all-inclusive admission that got you the game, some dinner, his book (signed) and a Q&A with him in the room usually reserved for Terry Collins explaining what went wrong with the bullpen in the eighth inning. I had partaken, as a civilian, in a similar deal for R.A. Dickey when he was promoting Wherever I Wind Up and found it a veritable bargain. One thing I noticed about Doc’s session, which we walked in on the tail end of, was Gooden lavished time and attention on every fan who asked for it, posing for pictures, chatting intimately, just being very available. It didn’t occur to me immediately that the reason he outstripped Dickey on that personable front was that R.A. — who was friendly enough but by comparison dished and dashed — had a team to get back to. Doc was there to be Doc. Legends-in-residence can set their own parameters.

When the last of the paying customers was done, we (maybe seven of us) were introduced on a first-name basis to Doc. As he went around our semi-circle, shaking our hands and greeting us personally, I had to seal all exits from my skin, for the next few minutes were about to become an out-of-body experience.

“Hey, you, sitting there — you’re shaking Dwight Gooden’s hand and he’s calling you Greg. Get a grip, literally and figuratively.”

Dwight Gooden has a very substantial right hand. It shakes quite well. It’s the same hand that won those 24 games, struck out those 268 batters and choked off opponents’ scoring at a rate of 1.53 earned runs per nine innings. I can still feel his right palm meeting my right palm the way I can still feel the only foul ball I ever legitimately caught — albeit on one bounce— landing in my left palm. That was in St. Petersburg, in 1982, less than three months before the Mets would draft a 17-year-old high school pitcher from across the bay in Tampa. Craig Swan was pitching for the Mets at Al Lang Stadium when I grabbed that ball with my bare glove hand. Almost two years later to the day, I’d be watching the 19-year-old Dwight Gooden pitching for the Mets at Al Lang Stadium.

Within a few weeks, in April 1984, Dwight Gooden would become Dr. K and it would never occur to me at his heights that I’d ever be shaking the hand attached to the arm attached to the best pitcher and my favorite player since Tom Seaver.

I listened to my fellow bloggers’ questions, I swear I did. I paid attention to Dwight Gooden’s answers, too. But mostly I had to mentally glue myself to my seat so I didn’t float away. Surreal doesn’t cut it as descriptors go. I was sitting across from Dwight Gooden, my second-favorite Met ever. If this was how I was handling an audience with Dr. K, just as well nobody ever let me achieve proximity to Tom Terrific. They might have had to have called security to have my hand removed from his.

I saw Doc up close once before, but this was different. He looked a little lost then. Here, he was in control of his narrative. Some combination of media coaching and rehab rules had kicked in, I imagined. It wasn’t like I hadn’t heard the basics of the story he was choosing to tell before this impromptu meeting. He’d been interviewed plenty since Doc was released and there were only so many answers he had for the questions that came up over and over.

What really got me here was the eye contact. Doc looked each of us in the eye. That had to be a rehab thing, right? “Face your demons,” I was guessing he was told as he worked to get better. I admired the way he locked in because I’ve never been good at it. I was in a school play once where the director told me to look the other actor with whom I was sharing the stage square in the eye and I just kept cracking up and ruining rehearsal.

All that staring into the window of the soul certainly gets your attention, though during the moments Doc was speaking to my blolleagues, my eyes wandered here and there. When you sit in that interview room at the proper angle, you can see out into the bowels of the stadium. They’re not very bowely yet, what with Citi Field not being that old, but this is field level without the field. It’s the ballpark’s basement. There’s a lot of action out in those bowels as everyone hurries hither and yon in pregame mode. In the span of no more than three minutes, I glimpsed both Jeff Wilpon and Cuppy promenading by.

Why, I asked myself, am I staring out into the bowels at them when I’ve got Doc right in front of me?

Finally, my turn to ask a question. I tried to think of something I hadn’t heard him respond to dozens of times. Because I was approaching the Torborg/Green era in my Happiest Recap research, I asked him about those days, my stated premise being you know, you were still “darn good” then (what a hard-nosed interviewer I am) even if the team was stuck in the bowels of the N.L. East.

Doc looked me directly in the eye and acknowledged there was a modicum of fun to be had in those days and definitely some good guys on that team — he name-checked Bret Saberhagen and Eddie Murray for their talent — but explained, “The chemistry wasn’t there.” If your second-favorite Met mentions chemistry, I decided it must a genuine component of winning even if it doesn’t show up in the box score. Gooden then pivoted from answering my question to a broader reminiscence of 1984 to 1989 when the Mets modeled an all-for-one and one-for-all ethos. “Guys would all go out to eat together,” especially those first few years when they were building toward a championship.

“When you win a World Series with a team,” Doc continued, never failing to look me straight in he eye, “those guys are always your teammates.”

Each of us having had a question and an answer, the semi-circle grew a little more informal, with more “what was it like when…” wonderings mixed in with a recovering addict’s affirmations that, in the spirit of Brandon Nimmo’s wisdom, it’s best to take everything one day at a time. For any Mets fan, it was a dream. We who were privileged to sit alongside the pitcher who authored 157 Met wins never mind three ghosted memoirs didn’t even mind that we were missing Matt Harvey’s first pitches to the Nationals. For me, it was a professional-type situation that defied standard note-taking. At the bottom of my last full page, this is what I scrawled in brackets, which I use to distinguish my thoughts from those of the speaker:

[“I’m looking into Doc Gooden’s eyes and I have to fight back tears.”]

I came close to welling up, but I pulled back on my ducts and remembered I was ostensibly a journalist, or at least a quasi-journalist here. I may have even thrown in another question for propriety’s sake, but was reveling in the moment too much to jot down a whole lot else. It wasn’t until after the PR folks gently nudged all of us apart that I felt something I can honestly say I hadn’t felt in decades.

I was overcome by the urge to call my mother and ask her to guess who I just spent like 15 minutes talking to…well, not me by myself, but with a few other people…Dwight Gooden, that’s who…yeah, Doc!…well, here’s how it happened…

Believe me, I didn’t have the desire to tell my mother much of anything that didn’t include an expletive while she was alive and there’s been little I’ve regretted not being able to exchange in the 23 years she’s been gone. But this was Dwight Gooden, and my mother loved Dwight Gooden. Maybe not exactly like I loved Dwight Gooden, but close enough during her baseball renaissance of 1984 to 1989, when whatever it was that got between us tended to thaw for a few hours if the Mets were playing.

Of course it did. We won the World Series with those guys.

And I’m almost getting welled up reading the Happy Recap of that encounter, Greg. Been on the emotional roller coaster with Doc too…from idol worship to anger and disappointment that he threw it all away to acceptance that he’s human like the rest of us and above all, a huge part of our history and a member of the family. My daughter is 19 and therefore only knows him from her Mets history lessons, but there have been so many times I’ve wistfully told her how I wish she could have not only seen him pitch but experienced what he made Mets fans feel, which is unmatched to this day.

Good extensive audio interview with Dwight Gooden here (forgive me if you’ve already linked to this at some point):

http://www.wnyc.org/story/307897-dwight-gooden/

For an ever-so-brief period of about six weeks late in the 2010 season, Doc Gooden was an executive vice president for the Newark Bears. His appearances at games briefly recreated the mid-1980s in gritty Newark. Alas, a relapse by Doc that offseason (apparently) led to the Bears and Dr. K going their separate ways.

If he is back with both feet firmly on the ground, then we all can’t be anything but pleased with that.

It’s good to know the man who made Shea shake after years of barely a rumble can still churn up the insides of a grizzled Met vet.

Outstanding. And despite your misgivings, you’ve got RA and you’ve got Doc, you should try and complete the Cy Young set if given the opportunity.

Beautiful post. I think it sums up what Doc meant, and means, to all of us. In the end, he was not simply a strikeout machine. He was human. We can appreciate what he means to us, despite the disappointment.

I would say that for a number of years, Mookie filled the role of Team Ambassador quite ably. And of course we all love Mookie. But he’s not Doc Gooden.

[…] revealed deeper personal issues, but beyond the rehabilitation and behind the eyes I swear still saw the ace within when I got to sit directly across from him for a spell this summer. He knows what he did on the […]