Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

“Fuck, 33, too soon.”

“No, dying in thirties is tragic. As is forties. Sympathy dissipates from there. Fifties is ‘such a shame’. Sixties is ‘too soon’.”

“Seventies: ‘a good run’.”

“And eighties, ‘a life well lived’. Nineties?”

“That’s a fucking helluva ride.”

—Axe and Wags, Billions

Where would have the Mets been last year without Pete Alonso? Or Jacob deGrom? Or Jeff McNeil? Or Seth Lugo?

I don’t know. Nobody does. Yet we impose that hypothetical upon the actual regularly as a compliment to any Met we think made a positive impact on our team’s fortunes. I’m not sure what purpose it serves. Why shouldn’t have we had the players who helped the Mets be better than they presumably would have been without them? The Mets secured the services of those players via legally recognized contractual processes. While it’s possible the parties might not have reached a mutually satisfactory agreement and therefore Alonso or deGrom or whoever wouldn’t have worn the uniform of our choosing, that didn’t happen.

Every Met who’s been a Met has been a Met when he’s been a Met. (Got that?) Musing that we would have been worse off had we not had a given Met at a given time seems a fatalistic offshoot of the dreaded “this is why we can’t have nice things” self-flagellation to which we too often reflexively resort when things don’t go as nicely as we’d prefer.

We can have nice things. We can have the players who do nice things. We might not maintain the exact aggregation necessary to achieve our hopes and dreams in this season or that, but let’s enjoy what we get when we get it (whenever we next get anything of a baseball nature). Let’s not assume every Met who performs optimally for us is a clerical error waiting to be rectified by a vengeful karma last seen wearing a Nationals cap.

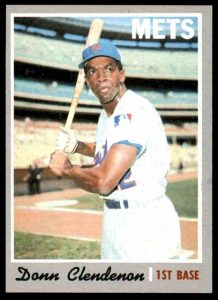

Where would have the Mets been without Donn Clendenon in 1969? Again, I don’t know. Nobody does. What we do know is that the Mets started 1969 with neither Donn Clendenon nor the slightest track record of success and that they ended 1969 with both Donn Clendenon and a world championship. If you wish to conclude that there is a direct correlation between the presence of the title and the presence of the slugging first baseman, go ahead. Clendenon was, chronologically speaking, the final member of the World Series roster to become a Met. Most of the 1969 Mets who made it to October were Mets before 1969. They didn’t win us any world championships before Clendenon came along, did they? Ergo, all that ticker tape must’ve sprung from Donn’s big bat.

That’s an awfully superficial way of determining a player’s intrinsic value to a ballclub. Still it’s tempting. The 1968 Mets had a whole bunch of their future champions already on board…yet lost 89 games. Plenty of 1969 Mets were 1967 Mets…but the 1967 Mets lost 101 games. Cover one eye, squint with the other and you can convince yourself that all the Mets of the late ’60s needed to transform themselves dramatically was Donn Clendenon donning orange and blue.

It was dramatic enough that Clendenon was traded for on June 15, 1969, in a deal that sent one fairly established major leaguer (utilityman Kevin Collins) and three minor leaguers of varying levels of promise (pitchers Steve Renko, Jay Carden and Dave Colon) to Montreal. It was additionally intriguing because Clendenon, a veteran of eight seasons with Pittsburgh, had rejected an earlier trade, in January, one that would have shipped him off to the Astros from the expansion Expos. Donn had been around long enough to know that he didn’t want to play for Houston manager Harry Walker and, unlike most ballplayers, he had an imminent and appealing career option outside baseball. Clendenon didn’t have to be an Astro when he knew he could be a Scripto (an executive for the pen company, that is). Montreal, which had drafted Clendenon from the Pirates, made other arrangements with Houston — allowing them to keep the erstwhile Astro they wanted, Rusty Staub — and held on to their ex-Buc a few months longer than planned.

The Mets had always angled to trade for a big bat of Clendenon’s caliber. They were just never successful at it. The best they could come up with was a bat that had been big — Ken Boyer in advance of 1966; Tommy Davis ahead of 1967; someone who’d put up some really fine numbers a while back and if he could regain some of that MVP-type form in New York, well, incremental improvement is better than none for a team that had yet to prove remotely competitive. The Mets were never successful enough for any trade to seem all that vital in the moment. The best they could do on the market was trade for what amounted to future considerations: prying loose 23-year-old Jerry Grote from the Astros in 1965 plugged a longstanding catching hole; landing 25-year-old Tommie Agee from the White Sox in 1967 accomplished the same end for center field. In a best-case scenario, both young men served as legitimate building blocks for a team that maybe someday wouldn’t be an automatic bet to finish in the second division, yet neither Grote nor Agee was acquired with an eye on climbing into first place at the very next conceivable opportunity. There was no conceivable first-place opportunity looming for the Mets in 1966 or 1968. Hallucinogenic drugs might have been gaining popularity in certain circles, but Harry M. Stevens didn’t sell them at the Shea concessions.

The exchange of players from June 15, 1969, however, transpired in a whole other beautiful world, one where Mets general manager Johnny Murphy could look at the roster he and his predecessors had been crafting when no one was taking them seriously and realize they were at last at the juncture when that mythic big bat could make a meaningful noise. Enter the strong, long and lanky Clendenon, albeit a couple of years removed from his most muscular production (28 home runs, 98 runs batted in and a .299 average in 1966 — adding up to an OPS+ of 141, not that anyone knew what the hell that was then). But the 1969 Mets, while they craved a legitimate cleanup hitter, didn’t necessarily have to have a superstar; nor were they willing to give up too much of their awesome young pitching to nab one. They needed someone who’d been around the league, someone who could get around on a fastball, and someone who would be OK playing sometimes. They needed a dependable right-handed hitting first baseman to complement their perennially developing lefty-swinging incumbent Ed Kranepool. Kranepool was 24. Clendenon was a month from 34. Between them, they averaged out as a 29-year-old switch-hitter, forging an ideal everyday player within Gil Hodges’s platoon of platoons.

The second-place Mets of mid-June 1969 were 30-26, better than they’d ever been after 56 games…and 8½ games behind the first-place Cubs. That only sounds like a large margin until you realize the Mets had never been far enough above .500 or near enough to first place to realistically measure themselves against lofty goals or stiff competition. Finishing in ninth place a couple of times seemed pretty heady stuff. But 8½ games out with more than a hundred games remaining and no one sitting between them and the team at the top constituted a legitimate shot. In 1969, the Mets were taking it. And they were taking Clendenon for the win.

You basically know what happened. I already gave away the ending. Donn Clendenon joined the Mets, and the Mets won the World Series. Clendenon’s impact was most helpful if not quite Cespedesian in its immediacy. Despite Donn delivering the kind of big hits befitting a big bat, the Mets of August 15 were actually farther from first place — 9½ out and in third — than they were two months earlier. But they were carrying a winning record, 62-51. They were unquestionably alive.

Then, in a hurry, they were alive and well and damn near unstoppable, racing up to and past the Cubs in what amounted to a blink. On September 24, with Donn Clendenon belting two home runs, the Mets beat the Cardinals to clinch the National League East. On October 16, with Donn Clendenon launching his third home run of a five-game set, the Mets beat the Orioles to win the World Series. Somewhere between showers of champagne, Donn was informed he had been named the MVP of the Fall Classic.

He hadn’t been a Met a year before. He hadn’t been a Met until four months before. Now he was certified most valuable, with the ultimate “nice thing” of its time, a 1970 Dodge Charger, to prove it. So, yeah, you can argue that for all the critical contributions made by every 1969 Met, they wouldn’t have gotten where they were going without Donn Clendenon grabbing the wheel.

But why would you want to think that we wouldn’t have had Donn Clendenon? Or any of the 1969 Mets?

Donn’s death was something else. Obviously, it was sadder. Are there ballplayer passings that aren’t? When we separate the occupation from the humanity, it’s depressingly logical that everybody eventually dies. That’s biology, though maybe it’s chemistry. I barely made it through biology and avoided taking chemistry. But a human who you know as a ballplayer…as a ballplayer from when you were a kid…even if it’s decades removed from when you were a kid and he was playing ball…I can’t say he’s not supposed to die, but it’s at odds with everything you love about loving ballplayers.

Donn Clendenon certainly wasn’t the first ballplayer from my youth to pass on, nor was he the first of the 1969 Mets to leave us permanently, but he was the first to go when I had this platform. We started Faith and Fear in Flushing in February 2005. When I learned Clendenon was dead, it was pure instinct for me to sit down at this very spot and remember him in pixelish print. I can’t imagine it would have occurred to me not to.

That’s been my self-assigned role ever since, sharing a few hopefully appropriate words on behalf of the deceased after a respectful moment of silence. A Met — technically “a former Met,” but once a Met, always a Met — dies, I try to make sure I have something to say on this blog about him. Same for any Met figure and often for others in baseball. But definitely when it’s a Met who shaped what it meant to root for the Mets, especially when it’s a Met whose name evokes the Series from when I was six and the summer from when I was seven. Donn Clendenon hit home runs two of the three times the Mets captured titles in 1969. He spent all of 1970 driving in runs: 97, for a new club record. He was at the core of my formative experiences.

May my science teachers forgive my perpetual difficulties absorbing their lessons, but someone who does that for a kid is not supposed to die, or at least not die so soon. Not that I can pinpoint where 70 falls on the spectrum of too soon. Do 70-year-olds rate the condescending “70 years young” treatment, or does that kick in when a person has made it to 80? I kind of remember that when I sat down to memorialize Clendenon, it felt a little different from what I’d been moved to write in other forums when John Milner, Tommie Agee and Tug McGraw died, to name three other Mets from when I was a kid. Milner was 50; Agee, 58; McGraw, 59. I was somewhere between 37 and 41 when they died. I could tell they were too young to go.

I was 42 when Donn Clendenon died at 70. Seventy, from the perspective of my early forties, seemed maybe (maybe) a little less cruel from an actuarial standpoint, but who was I to say? We the living can be haughty in making such appraisals. I did know that I found it was inherently surprising that the eternally young 1969 Mets had a 70-year-old alumnus. These days every living member of the 1969 Mets is at least 70 — and I’m fifteen years older than I was in 2005.

Without Donn Clendenon, am I quite the Mets fan I am today? I don’t know. But I know Donn Clendenon became the Mets’ big bat when I was six, and here I am, 57 years old/young, and I’m a Mets fan still.

For an in-depth examination of the remarkable life of Donn Clendenon, I highly recommend the SABR biography Ed Hoyt authored. You can find it here.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1994: Rico Brogna

That the Orioles’ 1 and 1A starters, Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally, were both lefties turned out very nicely for the Mets. Clendenon was the big bat of the Series for the Mets, but Al Weis our 1A hitter. Both would’ve been on the bench had they had a rotation full of righthanders (northpaws?).

I do remember him working for the pen company, but I believe he earned a law degree after he retired.

Coincidence by the way, I’m 15 years older than I was in 2005. That should make us the same age, but somehow it doesn’t. You barely made it through biology, I barely made it through algebra.

We futzed around with STEM and this guy on the METS grabbed a law degree in addition to an MVP.

Greg, have you ever done a post on Tommy Agee? It’s still surprising to me, over fifty years later, how the White Sox would deal away the 1966 AL Rookie of the Year, just a year later. Not sure if there was any reason behind his big drop-off in year two in Chicago. The Mets got Agee and Weiss for Tommy Davis, Jack Fischer and two minor league players. Wondering which side thought they won that deal?

Agee didn’t hit righties well in 1967 (under .200) which might have influenced the White Sox’ thinking. They were coming off a year when they almost won the pennant and perhaps they thought two solid veterans (the best kind) would help lift them. Instead, they fell back and mostly wandered the deserts of non-contention for another fifteen years. Not that all of that could be blamed on trading Agee.

Mets definitely wanted him, though. Glad they got their man.

[…] With & Without Donn Clendenon » […]

[…] METS FOR ALL SEASONS 1969: Donn Clendenon 1973: Willie Mays 1982: Rusty Staub 1991: Rich Sauveur 1994: Rico […]