I was five months old when the Mets completed their ascent from doormats to destiny’s darlings, and by the time I started collecting cards in 1976, the miracle makers had been largely dispersed. Just six were still Mets. The rest had become Pirates and Astros and Phillies and other questionable things, or started doing whatever people did when they no longer played baseball. Two were no longer with us at all.

In an era before videotapes, let alone YouTube, I learned the saga of ’69 through books, snapping up every quickie paperback I could find about the Miracle Mets. Which turned out to be a terrific education, as a lot of those books were genuinely great reads, thanks to a deep bench of talented New York sportswriters. George Vecsey’s Joy in Mudville, Paul Zimmerman and Dick Schaap’s The Year the Mets Lost Last Place and Maury Allen’s The Incredible Mets were particular favorites, with a special place in my heart reserved for Screwball, written by Tug McGraw with X amount of help from Joe Durso. And there was the peerless Roger Angell, whose meditations on baseball convinced me that other teams were sometimes worth pondering too. But I wasn’t discriminating — I’d read anything about the Mets, or that might be about the Mets.

That was how I learned the gospel. About Tom Seaver refusing to celebrate .500, and Gil Hodges taking the long walk out to speak with Cleon Jones. About the black cat and Leo Durocher and Ron Santo clicking his heels. About Frank Robinson calling Rod Gaspar “Ron Stupid” and the Met wives unfurling a banner in the stands in Baltimore. About the scoreboard saying LOOK WHO’S NUMBER 1 and the shoe-polish ball being brought to Lou DiMuro. I read about Tommie Agee and Ron Swoboda catching balls dozens of times before I ever got to see them do it, and could tell you in great detail how J.C. Martin should have been out but I was glad he wasn’t, despite no visual reference. I’d studied the picture of Jerry Koosman jackknifed in Jerry Grote‘s arms while Ed Charles danced happily nearby so many times that I could draw it from memory.

There was stuff I didn’t understand yet, like the controversy around Seaver and the Vietnam war and a flag that absolutely should or shouldn’t have been at half-mast, or why anyone thought it was significant that the Mets’ black and white players all seemed to get along. And there were random pieces of the adult world that those books lodged in my brain because of their Mets connection. I was foggy on who John Lindsay, Nelson Rockefeller, Jackie Onassis, Ed Sullivan or Pearl Bailey were, but I knew they were part of the tale and that was good enough for me. (I still don’t really know who Pearl Bailey was.) I knew it was funny that Swoboda had yelled, “they’ve sprayed all the imported and now we have to drink the domestic,” and repeated that endlessly despite not knowing why it was funny. Oh, and for some reason I could tell you that Nancy Seaver wore a tam o’shanter. (There it was atop her head in last night’s SNY airing of Game 4, just like the books taught me.)

But there were discordant notes in the saga, things that seemed strange to me but not to adults. Some of the Miracle Mets had retired because they were old, at least for baseball, but others had disappeared before their time — what had become of Gaspar, or Jack DiLauro? As I kept reading and learning, I figured out that Gaspar and DiLauro had been the last guys on the roster, the kind of guys who had to keep fighting for big-league jobs. But that still left one mystery: What had happened to Gary Gentry?

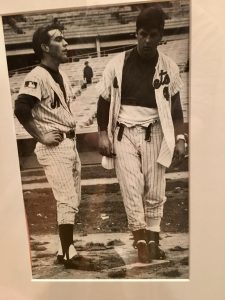

He’d been a rookie in 1969, and even I knew he was young for a ballplayer then. Heck, he even looked young to me, for whom everybody was old. One of my favorite Mets photos is of Gentry and Seaver standing on the mound after the Mets clinched the division and security guards wrested the field back from the sod-pillaging mob. Their uniforms are in disarray, as is the field. The photographer caught Gentry while trying to get his bearings in this strange new world, but the first thing you notice is he looks about 12.

I knew Gentry had been a good pitcher — a really good one, in fact, part of the Mets’ front line with Seaver and Koosman. But Seaver and Koosman were still Mets, and Gentry wasn’t. He’d become an Atlanta Brave, grown a mustache that made him look vaguely dissolute, and then vanished. The explanation given by Mets books and the occasional Baseball Digest mention was that he’d hurt his arm, which was both annoyingly vague and raised more questions than it answered. Was hurting your arm really that common? Could it happen to any pitcher?

The answers turned out to be yes, and yes.

I’d learn that eventually — a brutal baseball truth that in my mind will always be bound up with Gary Gentry.

As I got older, I realized that not all of the Mets had actually been baseball gods, and the ’69 championship had been less about destiny than superlative pitching, smart platooning and some good old-fashioned luck. (OK, so maybe there was a little destiny involved.) But Gentry really had been that good. He was a position player in high school, attending the wonderfully named Camelback High in Phoenix, before taking the mound for Phoenix Junior College and Arizona State. As a junior at Arizona State, Gentry went 17-1, fanning 229 in 174 innings; in the College World Series semifinal he went 14 innings against Stanford, striking out 15 and scoring the winning run. He was drafted by the Orioles, Astros and Giants, but his dad — a former World War II and Korean War pilot — refused to let him sign. The offers kept getting better, and after the College World Series Ed Gentry left the decision up to his son. Gary signed with the Mets for $50,000, blitzed through Williamsport and Jacksonville, and made the Mets out of spring training in 1969, when he was all of 22.

Gentry was two years younger than Seaver, but there were a lot of similarities between them. Gentry was smart, a student of the game eager to learn how to carve up enemy hitters. (The Mets put his locker between Seaver’s and Koosman’s, an excellent place to learn this craft.) He was ornery, though sometimes he directed his fire at teammates or management instead of the opposition. And, like Seaver, he had no patience for the dysfunctional romance around the Mets as lovable losers. Gentry’s juco team had won a national championship and just missed another one, he’d won a College World Series with the Sun Devils, and both his minor-league teams had been league champions. He wasn’t overawed by being a big leaguer, and he expected to win.

And he did. Gentry won 13 games as a rookie in ’69 and could have won 20 with better run support and less bum luck. (And, perhaps, with more ability to shake off misfortune — but, again, he was 22.) He won the division clincher, then started the NLCS capper against Atlanta (Shea Stadium’s first postseason game) and Game 3 of the Series, best known for Agee’s two sparkling catches. His performance against Baltimore came as a surprise to both Earl Weaver and Frank Cashen, who knew about Seaver and Koosman but whose scouting reports had badly underestimated Gentry. Years later, Cashen would still grow visibly irritated about the rookie who’d beaten his Birds — and Gentry, when asked, would still be irritated about Cashen being surprised.

(Oh, and he’s one of the most enthusiastic Mets belting out “You Gotta Have Heart” on the Ed Sullivan Show — behind McGraw, of course, and maybe Gaspar. Though nothing in that video will ever be funnier than Nolan Ryan, who can’t be bothered and doesn’t care that it’s obvious.)

After 1969 things went sideways for Gentry — sideways and then south. In ’71 Gentry groused about getting second-class treatment in the rotation and struggled with his emotions on the mound, repeatedly showing up teammates who didn’t make plays. He was still a prized commodity, though — the Angels settled for Ryan as the price for Jim Fregosi after being refused Gentry. In ’72 arm problems that had plagued him since 1970 became worse, and after the season the Mets traded him and Danny Frisella to the Braves for Felix Millan and George Stone.

As it turned out, Gentry had been pitching with a bone chip in his elbow, which the Braves’ doctors found after arm woes derailed his 1973 season. The operation to fix the chip would have been simple in 1970, but now it put him on the shelf for the rest of the year. He came back in ’74, but the highlight of his campaign was standing in the bullpen hoping to catch Hank Aaron‘s 715th homer. (Tom House caught it instead.) After another operation and lost year, Gentry returned for a third try in ’75, but feuded with Atlanta about a pay cut and wound up exiled to the bullpen. After getting shelled in a mop-up assignment despite being given minimal time to warm up, the Braves told Gentry he was being released to make room for younger pitchers. He was 28 and his arm felt fine, but he was done.

Done except for a tantalizing what-if. The Mets’ pitching staff was in tatters and they signed Gentry a month after Atlanta sent him home. He reported to Double-A Jackson with a promise that he’d be called up as soon as he showed the club all was well. Unfortunately, Gentry hadn’t picked up a ball in a month. He was in a hurry when he should have taken it slow. He warmed up for his first game, threw two pitches and heard something rip. Another pitch, another rip. He never so much as recorded an out for Jackson and went home to Phoenix to learn the real-estate business.

Remember when Jason Isringhausen and Bill Pulsipher were about to lead the Mets back to the top of the mountain, with Paul Wilson waiting in the wings? The debate was who was Seaver and who was Koosman and should we maybe be talking about Jon Matlack. But there was another possibility, a disquieting one that nobody wanted to mention. What if they all turn out to be Gary Gentry?

That wasn’t a knock on Gentry, but a knock on wood against the cruelties of baseball — a knock on wood that didn’t work. Only Isringhausen survived to have a notable career, and his top similarity score over on Baseball Reference isn’t Tom Seaver but Bob Wickman. As for Pulsipher and Wilson, they did indeed turn out to be Gary Gentry. Which might also be the fate of Noah Syndergaard. Or David Peterson. Or the next Met phenom you haven’t heard of yet.

What went wrong? You could blame Mets coaches, or Mets doctors, or their counterparts with the Braves, or any of a host of targets. But when it comes to injured pitchers, decades of advances in baseball science and sports surgery have brought us all the way from groping in the dark to groping in the dim. You wait for the pop, the shake of the arm, the visit from the trainer, the uncertainty and rehab and further uncertainty that follows, and it all still boils down to a simple, cosmically unfair truth about the game. Learning that truth was the solution to the mystery of Gary Gentry’s disappearance, a cruel lesson that generation after generation of Met pitchers has reinforced and will reinforce.

He hurt his arm. Pitchers break.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1994: Rico Brogna

Great piece on the fragility of pitchers. We can add Harvey to that list.

A fat load of good it does to say so now, but Gentry had a really violent motion and I guess in retrospect it isn’t surprising he threw his arm out. But boy, he had some performances in awfully big games for a 22 year old.

I remember a game he pitched in I want to say May 1970 against the Cubs at Wrigley, a one-hitter. The one hit was a sinking liner that bounced out of Cleon’s glove in left, ruled a hit. The 11 year old me was so outraged that I decided that I had the authority to overrule the official scorer and go around saying that Gary Gentry pitched a no-hitter. It was just so obvious, and of course the official scorer in Chicago couldn’t be trusted the year after the Mets humiliated the Cubs. The boxscore in the next day’s paper did not agree, nor did baseball historians.

I noticed that watching him on SNY this week. He threw across his body, lots of arm. I’m no Dr. Mike Marshall but it looked hard on the shoulder.

Jason, man, I have the book ‘The Incredible Mets,’ by Maury Allen, First Printing, November 1969, and I used to read it every Summer.

It is a Paperback and the cover price is 75 cents.

It is my favorite book.

And when I turn to the back cover, it says that it is due back to the Canarsie Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library on AUG 7, 1974.

Memories can fade a bit when one is almost 55 years old, but as I remember it, somehow the book became ‘misplaced’ in some box when we moved from East New York to Canarsie on JUL 27, 1974.

At any rate, let’s please keep this just between us, as, if and when the libraries do re-open, I would have a lot of explaining to do.

I have always loved that photo of Seaver and Gentry :)

Ugh, it’s hard to see it in print but it’s just so true about Noah. I don’t want too see him flame about before he figures it out and becomes what he’s supposed to be. I’ve been waiting since 2015 for the explosion. His game against Bumgarner in the one game playoff was magic even though we lost, and I thought we had a fireball ace for years to come after that for sure. Freaking sports

Oh well, at least Noah has plenty of time to recuperate this summer (…sigh…) And was it my imagination, or did the Mets actually sign Matt Harvey to a minor league deal just before the world got canceled? Another potentially fascinating story KO’d by Mr. Corona.

So, for which year is Gary Gentry the Met for all seasons after all? ’72? It’s not entirely obvious to me :-P

There’s nothing wrong with a Bob Wickman. Every team needs a Bob Wickman or two. They just won’t sell many shirts with his name and number on. The trouble starts when you have an entire roster full of Bob Wickmans. (looks at his team in OOTP Baseball and shivers)

And regarding David Peterson, I guess the Peterson in the link is not the same Peterson the Mets took in the first round? But even if so, what cruel beast of a manager had him pitch three innings for 23 earned runs, Backwoods League or not…?

[…] Pitchers Break » […]

[…] METS FOR ALL SEASONS 1969: Donn Clendenon 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1982: Rusty Staub 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1994: Rico […]