Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Richie Ashburn has two Topps cards as a New York Met.

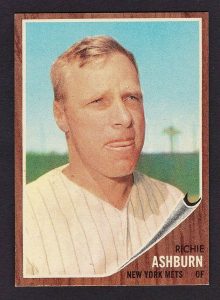

The first, his ’62 card, is what’s known in baseball-card circles as a BHNH. That’s “big head no hat,” a shot taken capless and from chest up, without the team logo showing. Such shots were insurance in case a player was traded — or, in this case, if baseball expanded and Topps had to include players with their new clubs before spring-training photographers got to work. Ashburn, hatless, is wearing Cubs or Phillies pinstripes. He’s working his tongue over his lower lip, as if he’s about to stick it out, and his brows are lowered. He looks perplexed, like he’s sizing up something strange and possibly dangerous.

Ashburn’s second Mets card is from ’63, and shows him in a proper Mets cap, looking heavenward, as if spying some greater reward. It’s what’s known as a “career capper,” one that includes a player’s full lifetime stats. Because Ashburn never suited up for ’63 with the Mets, or with anybody else after ’62.

Between those two cards lies a story.

Ashburn is one of the towering figures in the lore surrounding the 1962 Mets, they of the historically hapless 40-120 record and our year of consideration. But his role in that oft-told story is an interesting one. He’s not the jester (Marv Throneberry), the ringleader (Casey Stengel), the perpetual victim (Roger Craig), the shocked bystander (Gil Hodges), the sad clown (Don Zimmer), the guy in on the joke (Rod Kanehl), or one of the revealing cameos (Harry Chiti, Joe Pignatano, Choo Choo Coleman, the two Bob Millers as roommates). Ashburn was the straight man, the consummate professional at the center of the carnage and mayhem, perplexed by where he’d found himself and what he’d done to deserve it.

Which isn’t to say he didn’t have a sense of humor about it. Ashburn was Cyrano to Throneberry’s Christian, feeding Marvelous Marv lines from the locker next to his and turning a sad-sack failed minor-leaguer into a shambolic legend. He dined out on ’62 Met tales for years, or at least endured them, patiently answering fan mail and sprinkling the stories into his reminiscences in the Phillies’ broadcast booth and the Philadelphia sports pages.

You’ve probably heard those tales before, but they’re too good not to revisit.

The most famous yarn bestowed a name on a noted indie-rock band: Ashburn manned center for the Mets, but on pop flies he kept getting run over by Elio Chacon, the team’s enthusiastic but erratic Venezuelan shortstop. Eventually Ashburn figured out the problem was the language barrier, and enlisted the bilingual Joe Christopher to help. Christoper taught Ashburn that “I got it!” was “Yo la tengo” in Spanish. Ashburn tried out his new language skills on Chacon, who beamed. “Si, si, yo la tango.”

The next time there was a pop-up behind the infield, Ashburn hustled in to catch it and saw Chacon steaming in his direction. “Yo la tengo! Yo la tengo!” he hollered. Chacon obligingly pulled up and Ashburn camped under the ball — only to be knocked sprawling by Frank Thomas, the left fielder.

(By the way, when I was in college Yo La Tengo played a show in town and got a ride back to wherever they were staying, only to have the driver somehow mistake a pedestrian path for a city street, drive across our cross-campus lawn, and crash into a building. Which struck me as the ’62 Mets of indie-rock touring.)

But my favorite Ashburn story is a subtler one.

Ashburn and Throneberry each received a Chris-Craft cabin cruiser for their contributions to the ’62 Mets. Ashburn got his because he was voted team MVP, but Throneberry won his boat by hitting a Chris-Craft sign more than any other player. (This was the same sign that Thomas kept aiming for while at bat, eventually prompting an exasperated Stengel to holler from the dugout, “if you wanna be a sailor, join the navy!”) The team accountant informed Throneberry that he had to pay income taxes on his boat because it had been earned, while Ashburn’s boat was a gift and therefore tax-free.

That’s the shot, but here’s the chaser: Ashburn lived in Tilden, Neb., and had no conceivable use for a fancy boat. So he arranged for it to be moored in a marina in Ocean City, N.J., while he found a buyer. Whoever put the cabin cruiser in the water forgot to put back the drainage plug, so the boat sank. Then the check written for it bounced.

Yeah, 1962 was that kind of year. But on-field, Ashburn was the Mets’ brightest spot. He hit .306, a single-season mark that would stand until Cleon Jones hit .340 in 1969, and was the team’s All-Star representative. And that season followed a superb career, one that would lead to Ashburn getting the call to Cooperstown. Well, eventually. Which is part of our story too.

Ashburn’s father played semi-pro ball and would shape his son’s career, teaching him to hit left-handed to take advantage of his speed and grooming him as a catcher because he saw that as the quickest route to the big leagues. Noticing his son’s weak arm, he taught him to compensate through positioning, charging balls hit to him and making throws on the run — a technique that would become an Ashburn signature (and saved the 1950 pennant for the so-called Whiz Kids, as Ashburn nailed Brooklyn’s Cal Abrams at the plate in the season’s last game.)

In 1943 Ashburn signed with the Indians, only to have the contract nullified by Kenesaw Mountain Landis because he was just 16 and still in high school. The next year, Ashburn played in the Polo Grounds as an American Legion All-Star, where Connie Mack noted his speed and size and advised him to move off catcher. Ashburn signed with the Cubs, but Landis nullified that deal too because of a clause in the contract that would have paid Ashburn if the Cubs sold their Nashville farm team. Tired of false starts, Ashburn went to college despite being coveted by all of baseball, and had to be convinced to sign with the Phillies. His manager with the 1945 Utica Blue Sox, future Phils skipper Eddie Sawyer, was the one who finally forced Ashburn to quit catching — according to legend, that happened after Ashburn beat a batter to first, gear and all, on a grounder to the infield.

(By the way, Ashburn’s SABR biography is wonderful, and was invaluable to me. Read it here.)

Ashburn missed 1946 because he was in the Army — in a Metsian move, they sent him to Alaska — and made his debut in 1948 at 21. He was an immediate star, hailed as the best center fielder in the game and its fastest runner. Ashburn collected more hits than any big-leaguer in the 1950s, won two batting titles, led the league in hits three times, led or tied for the league lead in walks four times, topped 500 putouts four times, and played 730 games in a row.

After a subpar 1959, the Phillies traded Ashburn to the Cubs, where he always looked out of uniform. The Mets bought his contract in the winter of 1961, inheriting a player who’d lost some of his legendary speed but was still valuable.

The problem was that Ashburn hated losing. Which is the dark side of the ’62 Mets, the theme that usually stays submerged beneath the funny stories. Stengelese dominated headlines (and distracted the press from the wretchedness of the team), but there was no shortage of ’62 Mets who didn’t find their manager’s act particularly funny, or enjoy being National League doormats. Ashburn’s season came down to Sept. 30, 1962, a sparsely attended Wrigley Field matinee featuring two horrible teams. In the eighth, with the Mets trailing 5-1, Sammy Drake singled and Ashburn whacked a 2-2 pitch between first and second, singling and moving Drake up a base. Joe Pignatano came up … and hit into a triple play.

The next spring, Mets GM George Weiss — not known for being free with dollars — offered him a contract with a $10,000 raise. Ashburn said no. When an incredulous Zimmer asked why he’d retire after hitting .300, Ashburn said he couldn’t stand the idea of losing 100 games again. His ’63 Topps card became a retrospective of a career voluntarily cut short.

Ashburn finished up with 2,574 hits, which leads to a question that’s nagged at me for years.

He wasn’t inducted into the Hall of Fame until 1995, when the Veterans Committee voted him in. (His first call was to his 91-year-old mother, who wept with joy.) But calling that a grave injustice is too sentimental. Ashburn was a marginal candidate: He only hit 29 homers in his big-league career, and 82% of his career hits were singles.

But then there’s this. Ashburn would have been 36 on Opening Day in 1963. Granted, 36 was older for a ballplayer then than it is now, and Ashburn had lost some of the speed that was so important to his game. But he was still an effective player, racking up 119 hits in 1962. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to imagine Ashburn playing another couple of years with the Mets and winding up closer to 2,800 hits. (And let’s not forget he lost a year because of military service.) I don’t know if 3,000 hits was the magical number then that it became, but I do know that voters and veterans would have seen his candidacy differently a lot sooner if he’d come closer.

Instead, Ashburn walked away. He became a beloved broadcaster and columnist, a second act that cemented his legend in Philadelphia — next time you get to go to Citizens Bank Park, check out his statue in Ashburn Alley and offer a salute to his 1, retired since 1979. He died on Sept. 9, 1997 in New York, just hours after he’d enlivened a Mets-Phillies game with his usual dry commentary. (The Phils won, 13-4; the next night, Harry Kalas offered a heartfelt tribute to his longtime partner and the Phils won, 1-0, thanks to a Rico Brogna homer off Dave Mlicki.)

That’s a pretty good baseball life. But the part of it that can be statistically appraised was diminished because Ashburn couldn’t stand being part of a baseball joke. He got to be the straight man instead of the heel, sure. But he was still part of a comedy act, and the laughter didn’t sit well with him. And walking away didn’t free him from the farce, as that single miserable year in New York sometimes threatened to overshadow a dozen remarkable ones in Philadelphia. He was good-humored about the whole thing, but I sometimes wondered what he thought more privately, when the microphones were off and the writers had put down their pens.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

I never got the feeling that Ashburn was proud of his brief time with the Mets..He had a good year considering the team , but he always joked about it..Why not? I remember all those years he was interviewed about it. He treated it like a joke , really an embarrassment..Why not. Great hitter he was. he most certainty proved that in 62’…

…and $10,000 was probably some real money in 1963! Heck, I’d sign up for it right now. The Mets can put me in leftfield in a rotation with McNeil, Davis, and Dom Smith. You’ll hardly know the difference, I swear!

The tax accountant in me also can’t resist to point out that under German law, both those boats are subject to income tax, but the gifter can pay a flat token tax on the boat rather than letting the giftee tax it with his own personal tax rate.

Yeah, alright, I’ll be silent now. :D

[…] The Man Who Walked Away » […]

[…] METS FOR ALL SEASONS 1962: Richie Ashburn 1964: Rod Kanehl 1969: Donn Clendenon 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1982: […]