Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The 1986 Mets laid waste to the National League, closed bars, got arrested, wrecked planes, raised a prodigious amount of hell and opponents’ ire, got into fights, won most of those fights, defeated the Houston Astros in a harrowing six-game series, then defeated the Boston Red Sox in an even more harrowing seven-game set.

It’s annoyingly hard to remember, now that New York is infested by hedge-fund bros with corporate-logo vests and Yankee hats, but in 1986 this was a Mets town. And few teams ever fit their towns better than the ’86 Mets fit New York City. Everyone from everywhere else hated the New York Mets, but the Mets didn’t give a fuck what you thought of them, because what was the point of being from anywhere else?

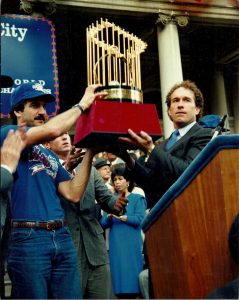

With the Red Sox done and no one left to vanquish, the Mets were given a ticker-tape parade and a ceremony on the steps of City Hall. Photos of the ceremony capture two ’86 Mets — the unquestioned leaders of the club — standing on either side of the World Series trophy they’ve hoisted into the air.

The man on the right is Gary Carter, the Mets’ tough-as-nails catcher and No. 4 hitter, a man with a sunny personality and a deep reservoir of faith. He looks like a kid at a church service — he’s wearing a jacket and tie and is shaven and scrubbed.

The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt.

The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt.

Both men, as it happened, celebrated the night before. But Carter went home at a reasonable hour (or at least one assumes he did, and it’s a safe assumption), got up, got dressed, and got himself to Shea Stadium in plenty of time for the 10 a.m. police escort to Lower Manhattan and the parade down the Canyon of Heroes. Hernandez stayed up all night boozing it with Bob Ojeda, went home at 7 a.m., woke up at noon, and only made the ceremony because Met fans recognized him and Ojeda and lifted them over a fence. Odds are he’s exuding a radioactive cloud of hangover sweat, and that Carter has looked over at least once and thought, “C’mon, really?”

It’s like Goofus and Gallant from the old Highlights feature, except for one thing: Goofus is there where he’s supposed to be. Gallant did a whole bunch of things that Goofus should have done and maybe now wishes he had done, but they both made the ceremony. They’re both holding up that trophy. And if you know the ’86 Mets, Gallant doing the right thing wouldn’t have meant a damn thing without Goofus as his bookend, doing what had to be done.

That was the Keith Hernandez I knew, the Keith Hernandez I adored, and the Keith Hernandez I wanted to be.

Look, I loved Gary Carter — he was simultaneously a truly decent human being and a ruthless competitor, which gave his successes against the likes of Charlie Kerfeld the moral clarity of a good parable. But I couldn’t imagine being him, or wanting to be him. Carter was straightforward and sunny and religious, and even at 17 I knew I wasn’t any of those things.

Meanwhile, some writer — most likely it was Chris Smith of New York, who wrote a string of wonderful Hernandez features back in the day — called Hernandez the hero of every guy who’s out until 3 a.m. but still gets the job done at work the next day. Keith’s reaction: “I thought that was well put.” That I could understand and take to heart. And I did: When I was younger there were most definitely office days after long nights when I’d bull my way to bleary-eyed success and think, Seinfeld-style, “I’m Keith Hernandez!”

That’s not to diminish Carter. But fundamentally, there are Gary people and Keith people, just like there are Mick people and Keith people and Chuck D. people and Flavor Flav people and Luke people and Han people. And I realized pretty early on that I was a Keith person.

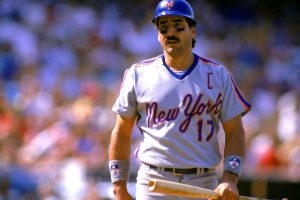

Next time they show Game 7 of the ’86 Series, stop and watch Hernandez’s crucial at-bat, the one in the sixth inning.

There he is staring out at Bruce Hurst with a combination of a surgeon’s concentration and a gangster’s impatient menace. He looks impossibly small and lithe compared with today’s players — today he’d be a fourth outfielder, maybe. When he was out of uniform his signature mustache struck me as distinguished, but that’s not the impression you got seeing it paired with an 80s mullet and unshaven face — staring out at Hurst, he looks like a pirate, or maybe a rock star.

The first pitch is called a strike; Hernandez reacts with indignant disbelief. Second pitch, bang! He pounces, that oddly long-armed swing uncoiling, and here come Lee Mazzilli and Mookie Wilson to cut Boston’s lead to 3-2. The camera jumps back to Keith on first base. He’s cool for a moment, standing there with Bill Robinson, and then the emotion overflows and he’s not so cool.

A first pump.

A yell.

That’s not enough, so one more of each.

“Yeah!” FUCK YEAH!”

That’s more like it.

We’re not done, though. The next batter is Carter, who hits a little flare that Dwight Evans rolls over in right field, leaving Hernandez caught in no-man’s land. He’s tagged out at second as Wally Backman scores the tying run. Being Keith, he starts hollering at umpire Dale Ford, as if Ford should have developed X-ray vision in anticipation of being blocked out. Ray Knight — Rusty Staub‘s successor as bodyguard/counselor to Hernandez — has to calm him down on his way into the dugout.

In a couple of minutes, you’ve been given a portrait of Keith Hernandez. Cool focus sharing space with fuming impatience, emotions boiling over, a bad idea not suppressed in time. That was Keith. But remember the context: all of that was the window dressing for a huge clutch hit. That was Keith too.

(And the rest? The blitzing through God knows how many watering holes in an all-night celebration? That was most definitely Keith. And so was getting to the parade on time, despite it all.)

All this seems preordained now that Hernandez is a fixture in the Mets booth and a New York icon. But it wasn’t — rather than arrive like a conquering hero, Keith Hernandez crept into town a stunned exile.

In 1986, William Nack penned an essential profile of Hernandez for Sports Illustrated, exploring the demons that drove him, denied him solace and also — cruelly — made him great. The story begins, as such complicated tales often do, with the father. John Hernandez was a first baseman who hit .650 his senior year in high school, good enough to be signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Playing under lousy minor-league lights in Georgia, he lost sight of a pitch, which hit him in the head.

His eyesight never recovered, dooming his career. So he taught his sons — Gary and his younger brother Keith — to play baseball. To call the elder Hernandez domineering would be to put it mildly: He’d berate his children for a single poor at-bat and give them written exams about defensive positioning.

Keith was the more promising athlete and tightly wound instead of happy-go-lucky like Gary, so he bore the worst of it. But his father was also an excellent teacher, and the best coach his son would ever have. Which he never let Keith forget — Nack chronicles boom-and-bust cycles of recrimination and rapprochement, with Keith complaining that he can’t stand the thought of his father watching his at-bats via a satellite-TV rig (which Keith bought), then needing him to diagnose a bad habit that’s crept into his swing.

(The story has a melancholy epilogue: John Hernandez died not long after his son’s playing career ended, with their issues largely unresolved.)

Hernandez battled insecurity and loneliness as a Cardinals rookie, overcame it with the help of veterans (Lou Brock and Bob Gibson were vital mentors, the first sympathetic and the second famously not), shared an MVP award, got married, got divorced, developed an infatuation with cocaine, kicked it, wound up in Whitey Herzog‘s doghouse, and was exiled to the hapless Mets in the summer of 1983.

His first reaction was to ask his agent if he had enough money to retire. Fortunately — for the Mets, for all of us, and for Hernandez himself — he didn’t.

Hernandez’s brother told him about the minor-league talent the Mets had in the pipeline. Staub took the new first baseman under his wing and told him that as a single guy he had to live in the city. And something wonderful happened to Keith Hernandez: Forced to become the on-field leader of a team that needed him, he found he relished the role and thrived in it, just as he found he loved New York and all it had to offer.

Instead of exile, he found a place for his best self to blossom. Three years later, he was a World Champion and a Gotham icon. In 1987, the recently departed Pete Hamill wrote that “New Yorkers don’t easily accept ballplayers. They almost always come from somewhere else, itinerants and mercenaries, and most of them are rejected. … Those who are accepted seem to have been part of New York forever. Hernandez is one of them.”

He was then and he is now. Has there ever been a more successful post-career second act in a Met life? One day, the Mets will retire No. 17 for him — and if they’re honest about it, they’ll retire it as much for his career in the booth and his simple existence as they will for the relevant lines in his Baseball Reference entry. Keith’s Mets career, while glorious, was a little too curtailed to merit a retired number in this fan’s opinion, but throw in everything he’s meant to the ballclub and its fanbase since then and he’s in a shoo-in.

In his role as a color guy on SNY, I confess that Hernandez can drive me batty. He’s often caught not paying attention, repeating something Gary Cohen or Ron Darling just said. And he can be disappointingly reactionary about anything new, whether it’s women in on-field roles (hopefully he’s grown out of that one), the shift, or a seemingly innocuous thing such as players carrying scouting reports in their pockets. Would a 15th-century Keith have hated the printing press? Do you have to even ask? It makes me crazy because it’s a tragedy for someone so ferociously smart to be habitually close-minded.

But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times?

But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times?

At some point in any broadcast, I’ll grumble at Keith being snide, dismissive or indignant. But I’m also guaranteed a moment where he’s being enormously entertaining — it might be lamenting the need to put a tent on this particular circus, exasperation at how long this is taking, or some random tale from his endlessly interesting life. And I’ll almost always turn off the TV with a greater appreciation for some fine point of the game. He was smart and impatient and complicated and sometimes his own worst enemy then. He’s the same today. I wouldn’t have him any other way.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

In December 2000, I was in what was then the Coach store on Madison @57th, doing some Christmas shopping.

I heard a familiar voice say “…yeah, but they’re the weakest 11-4 team I’ve ever seen.” I had had similar thoughts about the Giants that year, and turned and remarked “no kidding” to…Keith Hernandez, on one-o’-them portable phones.

He was approachable and gracious, pausing to discuss the team with me for about 30 seconds or so. As we split up, I told him that I was a die-hard Mets fan and that I knew that Game 7 was in the bag when he hit that single in the 6th inning (which might have been somewhat of an overstatement, but…he’s Keith Hernandez).

He thanked me and shook my hand. A class act.

Unlike Gooden, who completely missed the parade.

Having Gary Carter on your team was like having a devout cheerleader in the lineup and behind the plate, never giving less than his all until the final out was in the books. Having Keith Hernandez on your team was like having an extra manager who knew exactly what everyone should be doing at all times. You HATED them when they were on the other team but adored them when they played for yours.

One of so many Mets fans’ favorites for so many reasons; he’s funny both when you’re laughing with him or laughing at him, not just knowledgeable but able to explain the finest details and nuances of the game so that anyone can understand it, grouchy in all of the right ways, a fascinating life, and for those of us old enough to have seen his entire career, one of the best all around players I ever saw (and easily the best defensive player at any position). I loathe his politics and the venue of his most recent wedding, but I don’t tune in for that. We’re often jinxed when it comes to the team’s performance, but no baseball fans are more blessed when it comes to the tv booth.

So I guess he’s one of those Trump fanatics who refuses to wear a mask and believe the science.

In the ’90’s, Keith wrote a book called Pure Baseball, in which he attended a ball game (don’t remember which teams, but neither of them were the Mets) and broke down the entire game pitch by pitch in terms of what the players and managers were probably thinking. It was like reading a book written by a chess grandmaster breaking down a Karpov-Kasparov match move by move. And that was how Keith played the game – one of the most cerebral players ever. It’s what also makes him such a great color commentator today. He flat out knows the game of baseball like almost no one else. And no one ever fielded first base like Keith Hernandez did. Before or since.

[…] 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1983: Darryl Strawberry 1986: Keith Hernandez 1990: Gregg Jefferies 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1993: Joe Orsulak […]