Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

“People like to see human error when it’s honest. When people see you swing and miss, they start to root for you.”

— Paul Westerberg

I became a Mets fan in 1976, when the team had perfected an imperfect formula: combine superb pitching and defense with no offense and finish third. Miracle Met stalwarts Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman were still around, as were Jerry Grote, Wayne Garrett, Buddy Harrelson and Ed Kranepool, who’d always been around and one assumed always would be. Joining them were representatives of the Little Miracle — guys like Jon Matlack and John Milner and Rusty Staub.

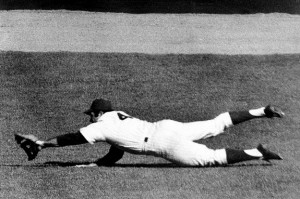

Staub was my favorite player, though of course I loved Seaver, rooted for Harrelson and appreciated Kranepool. But as a newly minted Mets fan with a dorky, proto-blogger’s bent, I hungered for history. Desperate to know what I’d missed, I inhaled books about my team — if the Emma S. Clark Memorial Library had a quickie book about the ’69 or ’73 team (or any other year), I read it and then immediately wanted to read it again. With DVDs and online video yet to arrive, I got most of my postseason lore from the written word and static pictures, from descriptions and reminiscences and snapshots and sportswriters’ flights of fancy. Tommie Agee in awkward mid-stride, a plume of white at the end of his arm. The unhurried way Gil Hodges strolled from the dugout to visit Lou DiMuro with a baseball in one big hand. Tug McGraw dodging and diving and weaving and bulling his way to the dugout. Willie Mays on his knees in vain supplication. Koosman jackknifed in Grote’s arms, with Ed Charles in the early stages of liftoff nearby. And, of course, Ron Swoboda — fully outstretched and parallel to the right-field grass, approaching an uncertain intersection with the ground and a baseball.

Swoboda was gone by 1976, but in every account of the ’69 Mets he loomed large. Not just because of The Catch, but because he was smart and funny and reflective and complicated. Which, though I didn’t know it yet, made him my prototype for what I wanted every baseball player to be.

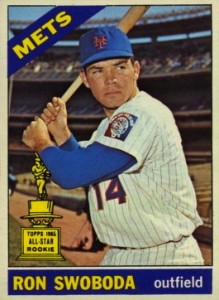

The lore was pretty thick around Swoboda even before 1969. He signed with the Mets for $35,000 in 1963 as a 19-year-old from the University of Maryland. (Ironically, given what came later, Swoboda was born and raised in Baltimore and had played high-school exhibitions in Memorial Stadium.) His last name is Ukrainian for “freedom.” In 1964, he caught Casey Stengel’s eye — the young slugger reminded Casey of Mickey Mantle — and was hyped as part of the Mets’ about-to-arrive Youth of America.

Casey pronounced his name Suh-boda, which stuck with fans. Teammates called him Rocky, a reference to his mental lapses in the field and his ability to say the wrong thing at the wrong time off of it. He came to the Mets to stay in 1965 — a callup he would come to regret — and became a fan favorite. Writers loved the fact that he had a Chinese grandfather, which wasn’t really true — his grandmother had married the owner of a Baltimore Chinese restaurant. Fans loved his ability to hit long home runs and sympathized with his outfield misadventures — you were never quite sure what Swoboda might do out there, but you were pretty sure it would be memorable. In his first big-league at-bat, a terrified Swoboda fell into an 0-2 hole against Don Drysdale, and considered it a triumph that he lined out to second. (“I felt like a fish that had been dragged into the boat and somehow managed to flop back out,” he’d remember.) Two days later, his second big-league at-bat produced a home run. RON SWOBODA IS STRONGER THAN DIRT, fans proclaimed at Banner Day.

In one game, Swoboda forgot his sunglasses, misplayed a Dal Maxvill fly ball into a triple, returned to the dugout in a fury, and stomped on a batting helmet. The helmet got stuck on his cleats and left Swoboda hopping around trying to dislodge it while Stengel turned the color of a ripe tomato. Casey pulled Swoboda from the game, asking, “Do I go around breaking up his property?” Another time, Casey groused that Swoboda “thinks he’s being unlucky, but he’ll be unlucky his whole life if he don’t change,” a bit of baseball wisdom I recycled later in life for Come to Jesus conversations with wayward journalists. Yet for all his misadventures, Swoboda hit 19 home runs in 1965 — a Met rookie record that stood until Darryl Strawberry eclipsed it 18 years later.

Swoboda managed the difficult and dubious feat of hurting his development as a ballplayer by alternately thinking too much and not at all. (Years after he retired, he admitted he still had nightmares about facing one of the great hurlers of the ’60s and not being able to get set in the batter’s box.) He wasn’t always popular with teammates, who were annoyed by his on-field mistakes and his off-field gift of gab. When reporters entered the clubhouse after a Met win, it wasn’t uncommon to hear someone yell out “Tell them about it, Rocky!” It should come as no surprise that one of his best friends on the team was the irrepressible, quotable McGraw. (The other was Kranepool.) But Swoboda was pretty quotable himself: In ’69, he was booed after striking out five times in one game, and opined that “if we lost, I’d be eating my heart out. But since we won, I’ll only eat one ventricle.”

1965, the year Swoboda represents in A Met For All Seasons, was a template for everything that followed — heroic moments mixed with ignoble ones. Four years later, it was still true: On Sept. 15, Steve Carlton struck out 19 Mets, with Swoboda accounting for two of the Ks … as well as the two home runs that beat Carlton. And, of course, there was The Catch. It wasn’t a particularly smart play — obviously he should have played it on a hop — except for the fact that hey, he actually caught it. “I had no time for conscious thought or judgment,” he’d recall. “The ball was out there too fast. I took off with the crack of the bat and dove. My body was stretched full out, and I felt as if I was disappearing into another world. … Somehow it happened. Somehow I got it. A miracle? Wasn’t the entire season a miracle?” In that one play the ignoble and the heroic did battle, the heroic came out on top, and because of that Ron Swoboda was a baseball immortal. As Tigers manager Mayo Smith put it, “Swoboda is what happens when a team wins a pennant.”

Two years after the Mets’ champagne celebration (“they’ve sprayed all the imported and now we have to drink the domestic,” he griped cheerfully, which became one of my go-to lines as a child even though I had no idea what it meant), Swoboda was traded to Montreal after one complaint too many about playing time. He hung around for a bit with the Yankees, failed to catch on with the Braves and was out of baseball by 29. He then began a long career as a broadcaster, one that would take him to New York and Milwaukee and Phoenix and New Orleans.

He was a sportscaster in New Orleans when I arrived there in 1989 as a pathetically green Times-Picayune intern, and a lot of people I came to know at the newspaper knew him. This finally registered with me when the woman I was dating mentioned in passing some bantering exchange she’d had with him. She had no idea that I was a Mets fan, and must have wondered why I stared at her in amazement. She knows Ron Swoboda. Which means I could meet Ron Swoboda.

The idea terrified me — I was a kid, and incapable of thinking of him as a fellow journalist. I’d read about him and looked at pictures of him since I was seven years old. He was a Met, a World Series hero, the man who made the Catch. He was Ron Swoboda. Meet him? And then what? It would have been like chatting with Zeus. (I did meet him a couple of years ago, after a ’69 Mets panel in midtown, and while he was perfectly nice, it was brief and dopey. In an uncharacteristically wise move, I didn’t mention having avoided him in New Orleans.)

When we grouse that ballplayers don’t seem smart, most of the time what we’re really lamenting is that they aren’t much for self-reflection. There’s an entertaining W.P. Kinsella story called “How I Got My Nickname” in which the ’51 Giants are all hyperliterate gents given to pondering the cosmos, a story that works because it’s immediately and obviously a fantasy. Back in ’92, Kelly Candaele (Casey’s sister) penned a great piece in the Times in which, among other things, she wondered about the fact that her brother and his teammates didn’t lie awake thinking about their purpose in life. When she asked Astros shortstop Rafael Ramirez about that, his answer was, “When I wake up in the middle of the night, it’s because I want a sandwich.”

I don’t assume baseball players are dumb — I’m amazed at how many of them can analyze pitch sequences and find little tells during the game, and how they remember at-bats in vivid detail years later. Beyond their superhuman physical talents, many of them have an extraordinary ability to focus that most of us don’t know enough to understand we lack. But self-reflection? I suspect most of them are like Ramirez, and probably better for it. When you make a living playing a supremely difficult, maddeningly unfair game, self-reflection isn’t necessarily an asset — better to let the moment go and start fresh.

There are exceptions. Players like Seaver or Darling or Keith Hernandez can dissect baseball like generals or prize-winning academics and focus that same lens on themselves. The 2000 Mets had three such players in Al Leiter, Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile — all smart, complicated guys who weren’t afraid of being interesting. But those players are exceptions that prove the disappointing rule.

The first Met I knew of who was exceptional like that? It was Swoboda.

It’s clear that he spent his share of middle of the nights lying awake, and not because he wanted a sandwich. He isn’t just a good quote, but also bracingly honest about himself. (You’ll find great interviews with him — the sources of many of this post’s quotes — in Stanley Cohen’s A Magic Summer and Maury Allen’s After the Miracle.) He’s talked wistfully about he never got along with Seaver, admitting that he was the one who sabotaged any chance at friendship. “I wanted to be the best in the game at my position; I wasn’t,” he said. “He just made it look so easy, was so good — and it just frustrated me so much.” And he’s told the story of confronting Hodges in the clubhouse bathroom over his use of Kranepool — after which, feeling his manager’s glower on his back, “I was standing against the urinal and I couldn’t pee.”

Of course, Swoboda will always be bound up with 1969 and the Miracle Mets — a bit of typecasting he has accepted cheerfully. (“How long am I going to make a living off of one catch? How long have I got left?”) That’s no surprise, but Swoboda’s reflections on ’69 have almost invariably been interesting, too. “We were ingenues,” he recalled once. “We had that wonderful, clear-minded innocence of not having the responsibility of winning it, of not having to doubt ourselves if we stumbled, and that’s a marvelous state to achieve.” Another time, he said that 1969 “wasn’t destiny. I don’t believe in destiny. What I believe is you can get to a state where you are not interfering with the possibilities.” That’s a long way from taking them one game at a time, pulling together as a team and all the other rote nonsense players have been taught to say so that reporters go away as quickly as possible.

And Swoboda has always understood what that summer meant to the fans, and refused to see what he did and what we did as disconnected. He has always been willing to bridge that gap, and make us feel like it doesn’t have to exist, even though he and we know better. “I never felt above anyone who bought a ticket — I just had a different role than they did,” he’s said. “We were part of the same phenomenon.”

The ’69 team was heralded at Citi Field during its first summer, and I of course cheered for all of them. I applauded the McAndrews and Gaspars and Dyers, cheered for the departed Tug and Gil and Donn and Don and Cal and Tommie and Rube, and gave Seaver and Koosman and Ryan their due, as one must. But the player I cheered longest and loudest for from that team?

It was Ron Swoboda. It always has been.

If you’re a veteran reader with a sense of deja vu, no, you’re not going crazy — this post appeared in much the same form back in 2010. Hey, I got it right the first time.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

There was a game in 1969 in which Swoboda struck out 5 times, but the Mets won. Looking it up today on baseball reference, it happened in June against the Cardinals. The only reason I remember it is because of what he was quoted as saying after the game, which my brother and I read the next day in Newsday.

I’m paraphrasing the quote as I remember it from 51 years ago.

When you strike out 5 times in a game the fans should line up on the road and boo you all the way home. If we lost the game, I would cut my heart out. Since we won, I’ll only cut out one ventricle.

Since then my brother and I always referred to Ron as “Ventricle Man.”

GREAT post! Anyone who quotes Paul Westerberg is ok by me. I’m always “satisfied.”

Interesting quotes by Swoboda: “What I believe is you can get to a state where you are not interfering with the possibilities,” and “We were part of the same phenomenon.”

Very EST… It was a “synchronous” team achieved its potential and “generated” a future no one foresaw.

“What I believe is you can get to a state where you are not interfering with the possibilities.”

Sounds like a quote I truly love, and one that affects many and most of us, in all lines of work:

“Imagine what we could accomplish if we were not held back by our own fears.”

That 1969 team just let it flow, and never got in its own way, and look what they accomplished.

“I became a Mets fan in 1976, when the team had perfected an imperfect formula: combine superb pitching and defense with no offense and finish third.” – well, uh, at least they were good at *some*thing! =)

And I’ll gladly copy “I had no time for conscious thought or judgment” into my permanent repertoire of unhelpful excuses for having fudged up, including an attribution to Mr. Swoboda, who nobody I know has ever heard of. :-P

[…] METS FOR ALL SEASONS 1962: Richie Ashburn 1963: Ron Hunt 1964: Rod Kanehl 1965: Ron Swoboda 1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: […]