Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The golden age of baseball coincides neatly with when one happened to be twelve years old.

—John Thorn, Official Historian, MLB

If first base is childhood and second base is adolescence, the summer you’re twelve years old is your indecisive third base coach putting on and taking off the steal sign so often that you might want to call time. The summer I was twelve years old, 1975, I stayed close to first, but I had my eye on second. No wonder, then, that as summer grew late, I took off for second — and, as summer was turning to fall, ran straight toward the newest of Met stars, Mike Vail.

As Met metaphors go, you had to be there, and I was. I was with the Mets practically every minute of every day in 1975, treasuring the successes of the lingering icons of my childhood while savoring the accomplishments of the unusually large quantity of newcomers who had joined them. Seventeen Mets made their team debuts in ’75, the most in any season since notoriously transient ’67. They were breaths of fresh air, though I don’t mean to imply the extant atmosphere was wholly stale, for I also took comfort that the foundation of 1975 was formed by figures so familiar to me.

It could still be 1969 if you wanted it to be. Tom Seaver pitched as Terrific as ever (22-9; 2.38 ERA; a league-leading 235 strikeouts). Jerry Grote regularly caught the two- going on three-time Cy Young winner. Bud Harrelson was still around, at least when the disabled list didn’t beckon. Wayne Garrett, too, no matter how often they tried to replace him. It could be any year in Mets history when you saw Eddie Kranepool grab a bat and emerge in the on-deck circle. Jerry Koosman notched a couple of saves, once stole second base and pulled down 14 wins. Cleon Jones, who’d been piling up hits for the Mets since 1963, missed time early, but eventually returned. By July of ’75, Jones’s collection of singles, doubles, triples and homers was up to 1,188, the most in Met history.

It could still be 1973, too. Felix Millan played in every game. Rusty Staub drove in runs at a franchise-record pace en route to becoming the first Met burst past a hundred ribbies. Jon Matlack was so good, he wasn’t only an All-Star, he was the Midsummer Classic’s co-MVP, with Bill Madlock, because who could resist the homophonic possibilities? John Milner was on hand, if in a slump. Ron Hodges was in the minors, but not permanently. Harry Parker had put down stakes in the bullpen. The callups from a couple of years earlier were making strides — Bob Apodaca (13 saves) more so than Craig Swan (6.39 ERA), but strides were strides. George Stone, who might have been asked by Yogi Berra to start at least one more game in a recent October, was thought more or less recovered from arm problems. Yogi managed as he had in 1973, though apparently not enough, because he didn’t last the duration of 1975. Then again, neither did Jones, who had a falling out with Berra, which led to an unconditional release that reads as unthinkable in retrospect, but real time didn’t sit still to take stock of how good a player used to be. Jones was, in the middle of 1975, a .240 hitter judged insubordinate by his manager. Berra was a manager whose alleged contenders trailed Pittsburgh by 9½ at the two-thirds mark. Berra was next an ex-manager, replaced by coach Roy McMillan.

Cleon and Yogi had had it already by the summer of ’75, but they weren’t the only ones for whom it had been called a day in Flushing. The all-time Met hit king, who had batted .340 in ’69 and sizzled through September of ’73, was shown the door not only weeks before Yogi was told it was over for him, but also not so many months after Tug McGraw, Ken Boswell, Duffy Dyer, Don Hahn and Ray Sadecki were dispatched to distant precincts following the massive Met disappointment of ’74. They’d all been heroes of or at least contributors to pennant drives past. But past was past. Thank you for your service. The present is presently all that is accounted for.

So maybe most days it couldn’t be 1969 or 1973, but as a 12-year-old, maybe I didn’t want 1975 to be moored solely to what had been. I loved all we’d pulled off when I was 6 and again when I was 10 — it helped explain why I’d been a Mets fan literally half my life — but I sort of wanted to move forward, to race toward second, as it were. I didn’t want to be merely satisfied by the presence of old faces. I wanted to be excited by new faces. Old faces that looked different once they were under a Mets cap would suffice just as well.

Joe Torre, whose 1967 baseball card was my first, now wore a Mets cap as he attempted to dislodge Garrett from third. So did Jesus Alou, who had played in the same outfield with his brothers in 1963, against the Mets, just after Cleon Jones was initially promoted. Alou was a .350 pinch-hitter from the right side, complementing Kranepool’s .400 clip from the left. Del Unser had been around. Now he was a Met, and a superb one at that; should’ve made the All-Star team, I’ll never tire of mentioning. Gene Clines was always a Pirate. Now he, too, was a Met. Likewise former Astro Bob Gallagher, former Giant Mike Phillips, former Red Tom Hall and a couple of American League relievers who existed for me mostly in the pages of Baseball Digest: Ken Sanders and Skip Lockwood. Big Dave Kingman, who in 1971 simultaneously socked a home run off both Jerry Koosman and a bus minding its own business in the Shea Stadium parking lot when visiting from San Francisco, was suddenly a Met, purchased in Spring Training. Soon Sky King (don’t call him Kong) owned our all-time single-season franchise home run record, a mark I assumed by law would always belong to Original Frank Thomas.

We had imports representing varying degrees of exotica and we had kids of our own breaking through the grass ceiling and introducing themselves as Mets in full. Rick Baldwin, 21, put on Tug McGraw’s 45 and got warm in the pen. Randy Tate was almost as young and just as new; he wore 48 and almost threw a no-hitter (which is to say he didn’t, but still). Another rookie, John Stearns, accompanied old Del Unser and fairly familiar if frighteningly fleeting one-game wonder Mac Scarce from Philadelphia, so technically Stearns wasn’t homegrown, but he was as fresh-faced as it got behind the plate on the days Grote wasn’t catching. If you read the Sporting News, as I began to the summer I was twelve, you salivated at the realization that we had a third baseman coming along who was leading the International League in runs batted in. His name was Roy Staiger and he, too, would be elevated to the majors by the Mets in 1975.

Move over, Garrett. Move over, Torre. Staiger’s here! Oh, the things I thought when I was twelve.

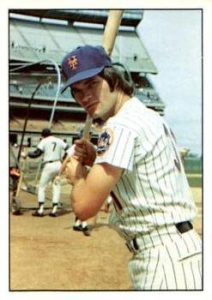

This blended roster-family of old, new and newish gave me many a moment and milestone across my seventh season as a fan. But the player who punctuated all this dizzying activity most tantalizingly — not with a period, but with an ellipsis, as if to indicate there was more to come — was Mike Vail, a heretofore underpublicized August callup who electrified September. There was no deafening buzz that I can recall soundtracking the promotion of Mike Vail. Vail hadn’t habitually haunted the back pages of the Official Yearbook. He wasn’t hailed as a Future Star and had never gotten our hopes up.

Unless you were tracking the St. Louis Cardinals’ farm system (where he’d been fellow Northern Californian Keith Hernandez’s roommate), you probably hadn’t heard of him a year earlier. I’d heard of him only the previous fall when I’d read that he was the throw-in to the deal that sent utilityman and 1973 alumnus Teddy Martinez to the Cards for utilityman and former Indian Jack Heidemann. If you’re considered the extra guy in a trade that swaps who’s slated to sit, you’re just asking to be overlooked. For whatever reason, Vail’s name, however small the type it might have been printed in when the papers first reported his acquisition, stuck with me immediately and stayed with me indefinitely. Yeah, I thought, we got a lot of new guys for next year, but nobody’s talking about Mike Vail. I was feeling a little pride of propriety in his forthcoming fortunes. Maybe I figured we who sported punchy two-syllable names had to stick together.

Coming into 1975, Vail was 23 and a four-year minor league veteran. It’s not as if the numbers implied he couldn’t hit. In ’74, the righty batted a combined .334 at Single-A Modesto and Double-A Arkansas, but promising outfielders in the Cardinal system had to wait in line behind Lou Brock, Bake McBride and Reggie Smith. St. Louis was set. Vail grew antsy and requested a trade. To show just how sophisticated the scouting of prospects could be in bygone decades, GM Joe McDonald detailed for the Sporting News the intricate strategizing he undertook with his Cardinal counterpart, Bing Devine, in order to land Mike on the Mets.

“When Bing and I decided to swap Martinez and Heidemann,” Joe said, “I felt we needed another player in the deal. I asked for Vail, and Bing said OK.”

The 1975 yearbook’s YOUNG MEN WITH A FUTURE page featured eight players; none was Mike Vail. Instead, Vail rolled in with the Tides. He proved high Tide. Highest International Leaguer, in fact. Mike hit .342 at Triple-A, better than every player in his circuit (Pirate infield hopeful Willie Randolph was IL runner-up, with a .339 average; Ellis Valentine in the Expo chain finished fifth, at .306). A big chunk of that .342 was built on a 19-game hitting streak that pretty much compelled his callup. His AAA season was enough to earn him International League MVP honors, a prize never before won by a Tide and something snagged the year before by Jim Rice, who was only propelling the Red Sox to first place in the AL East this year. Thus, despite no springtime hype, and no play on page 58 among the rising Brock Pemberton, Rich Puig and Luis Rosado types, Vail hit his way to New York, debuting on August 18 and validating my determination to let his name rattle around in my consciousness all summer.

At the time, the Mets’ outfield seemed to invite little in the way of flux. They may not have been Brock/McBride/Smith, but in right, incumbent Staub was on his way to pounding out those team-record 105 RBIs; in center, former Phillie Unser had settled in nicely en route to posting a .294 average; and in left, Kingman was taking dead aim at Thomas’s franchise mark of 34 home runs, a total that had sat undisturbed since 1962. Then again, Kingman (who had usurped Jones’s position before Cleon’s tenure met an ignominious end) was said to be versatile, having played first and third for the Giants…and, quite frankly, he wasn’t putting down defensive roots in left. The Mets were scuffling to remain viable in the division race, hovering a little above .500 and clinging unconvincingly to wishing distance of the first-place Pirates. A team in the Mets’ position could hardly turn down a .342 batting average, regardless of its league of origin.

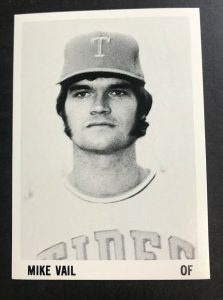

Mike, whose publicity photo revealed a Prince Valiant haircut, had to take his first NL swing inside the Astrodome against fireballer J.R. Richard, as intimidating an hombre as any rookie could encounter. Talk about being welcomed to the big time. Yet Vail announced his presence with authority, producing a pinch-hit single. Logging a 1-for-1 and holding a 1.000 batting average was not an inauspicious way to get Vail’s party started.

Soon Mike’s soirée became a full-time affair. He got his first start in left on August 20. The position became his for keeps on August 25. With corner outfielders Vail and Staub flanking a platoon of Unser and Clines, the Mets commenced contending in earnest. The club that had faded behind Berra discovered depth behind McMillan. Late August wound down with a five-game winning streak in Southern California and the Mets creeping to within four lengths of the Pirates. Seaver, Koosman and Matlack threw complete games in succession. Kingman was up to 28 homers. Staub had 90 RBIs.

And Mike Vail was the hottest Met of all. In San Diego, he went 9-for-14. In L.A., he notched a hit a day. When the Mets returned to Shea to open September, Vail belted his first home run, off John Candelaria, to give Tom Seaver a 1-0 first-inning lead. It was all Tom would need en route to completing a four-hit shutout. It was not only Seaver’s 20th win of the year, it included his 200th strikeout of the season, the eighth consecutive season he’d fanned at least that many. It was an all-time baseball record and it rightly received the lion’s share of attention that Labor Day afternoon.

But if you were paying attention, you couldn’t help but notice that Mike Vail had hit in nine games in a row. And once the Mets leveled off and unfortunately fell away from their chase of the Pirates, you mostly noticed that Vail had kept hitting, at least one hit in every game as September got going. On September 3, the day I started junior high, Vail’s streak reached ten. On September 7, as the Mets finished a dishearteningly dreadful homestand (they’d won both of Seaver’s starts but dropped their four other contests), the streak stood at 14. A three-game sweep by the Expos at Jarry Park essentially buried the Mets’ divisional aspirations — they were nine out with eighteen to play — but Mike just kept getting mightier. He hit in every game in Canada and now claimed a hitting streak of 17.

Did you know what the record for a Met hitting streak was? In the course of 1975, we’d been reminded that among Mets Tommie Agee had collected the most hits in a season (185), Donn Clendenon had driven in the most runs (97) and, of course, Frank Thomas had the most homers (34). Those standards were in the course of being refashioned by Millan (191), Staub (105) and Kingman (36). But streaks don’t build over a season. They appear out of nowhere, not unlike their architects sometimes. Vail was a throw-in when Felix, Rusty and Sky, not to mention Tom, Jerry and Jon were excelling. Now Mike was front and center for us, and Jack Heidemann (.214 in limited action) could be considered the throw-in to the Vail trade.

The record for a Met hitting streak was 23, established by erstwhile Met left fielder Cleon Jones in 1970. This was getting mentioned regularly. Ditto for another nugget: the record for a hitting streak by a National League rookie was also 23, shared by Joe “Goldie” Rapp of the 1921 Phillies and equaled in 1948 by another Phillie — and Original Met — Richie Ashburn. The division title hopes were gone. Seaver’s quest for the Cy Young appeared secure. There was time for Staub and Kingman and Millan to do what they were trying to do; even Millan’s goal (or our goal for him) of playing every single game, something no Met had ever done, would have to wait to unfold, one by one, until it got to 162. What Mike Vail was doing was all about immediacy, the fierce urgency of now. He was, as a new late-night television show set to debut in about a month would announce itself, live from New York.

Mike Vail had breathed life into the cause surrounding a team otherwise running out of time. As fans, even when we’re 12-year-old fans, maybe especially when we’re 12-year-old fans, we need a cause. In September of 1975, we needed Mike Vail’s hitting streak to keep on keepin’ on.

On September 10, the Mets traveled to Pittsburgh for a two-game series that no longer much mattered in the standings. Seaver lost the first game. Koosman won the second. Vail hit in both. The streak reached 19. The succeeding weekend brought them to St. Louis. Folks at Busch Stadium got to see what Devine deemed expendable. Vail went 1-for-3 on Friday the 12th; 2-for-5 on Saturday the 13th; and 1-for-4 on Sunday the 14th. The former Cardinal farmhand was now a lifetime .347 major league hitter riding a hitting streak of 22 games.

On Monday, September 15, the Mets welcomed Montreal to Shea Stadium. Steve Rogers was the opposing pitcher. Rogers retired Vail on a grounder in the first and a hard liner in the fourth. In the sixth, however, with the Mets trailing by two and Unser on second, Mike’s golden rap came at last. It was a single to center. The Mets halved the Expos’ lead but, honestly, more important was all at once Vail tied Goldie Rapp, Richie Ashburn and Cleon Jones. It was as long a hitting streak as ever forged by an NL rookie; by a New York Met; or any player anywhere in 1975 — the longest in that last category.

I, alone in my bedroom, went suitably nuts. The sparse Shea crowd of 7,259 that had been chanting, “LET’S GO MIKE!” stood and applauded for two solid minutes. But they’d have a little more to cheer two innings later when, with the score tied, Vail came up again, this time with runners on first and second, and stroked another single off Rogers, this one to left. Gene Clines came home to give the Mets a 3-2 edge, one maintained in the ninth on Skip Lockwood’s first Met save.

What a maiden voyage into the big leagues for Michael Lewis Vail. In crafting his record-tying streak, he batted .364, with 36 hits in 99 at-bats — a “steady rat-atat-tat of base hits,” in Jack Lang’s beat-writer lingo. Better than the numbers was the hope he represented. The Mets hadn’t developed many hitters in their 14-year history, hardly anybody beyond Cleon Jones and Ed Kranepool when it came to Met longevity. Mike might not have been seeded on the farm, but he did hone his skills as a Tide, and we Mets fans embraced him as our shiningest future light.

The streak ended the next night in an eighteen-inning game (Mike went 0-for-8), but the brief rookie campaign had worked its magic. Vail concluded 1975 with a .302 batting average and a grip on the Metsian imagination. When Joe Frazier, his skipper with the Tides, was introduced as the Mets’ next full-time manager, one of the questions Frazier received was whether he had any more Vails down there. Joe and everybody at the press conference laughed, because, yes, that’s exactly what we needed. More Mike Vails. More record hitting streaks. More future. We’d seen so many icons of 1969 and 1973 go. The day after the ’75 season ended, our first manager, Casey Stengel, died. On the day the ’75 playoffs started, our only owner, Joan Payson, passed on, too. Yes, we could really use some future around here.

Instead, we got a slap in the face come December when McDonald’s track record for offseason heists went off the rails. At the urging of de facto showrunner M. Donald Grant, the GM got rid of Rusty Staub before Rusty Staub accrued the contractual ability to veto trades. The news was dispiriting as all get out: Staub and Tide pitcher Bill Laxton to Detroit for Mickey Lolich and minor league outfielder Billy Baldwin. Lolich, 35, had been a helluva lefty for the Tigers…several years earlier. Staub, 31, was at his peak as a Met, both as an icon and as a hitter. He’d stay at his peak in Detroit. After driving in 105 runs for the Mets in ’75, he’d average 106 runs batted in for the Tigers across 1976, 1977 and 1978. (And, by the by, Baldwin wasn’t destined to morph from throw-in to steal.)

The only aspect of the Staub trade that made the transaction remotely palatable didn’t emanate from contemplating whatever Lolich might do in a new league. It was from knowing that at least the way had been paved for Mike Vail to continue developing as an everyday player. True, he’d played left for the final month-plus of 1975, and he’d be assigned Rusty’s old perch in right in ’76, but if Dave Kingman could be versatile, so could Vail. At least we’d have that to look forward to.

Except, no, not really, because Mike played a little hoops in the offseason and dislocated his right foot on the court. The damaged Achilles tendon kept him off the baseball field until June. The Mike Vail who returned wasn’t the Mike Vail we remembered. He batted .217 as a part-timer and never strung together more than five consecutive games with at least one base hit in all of 1976.

Meanwhile, Frazier’s management style didn’t win many games after ’76, nor did it retain the confidence of those making the decisions above him. He was gone before June of ’77. Others would be gone in June of ’77. The less said about the post-Payson ownership situation in the late 1970s, the better. The future that awaited Mike Vail and the Mets was not much future at all. Mike didn’t light up anybody’s life in 1977, leaving him to be claimed off waivers by Cleveland in the Spring of ’78. We’d see him again quite a bit as a Cub, for whom he once blasted an eleventh-inning grand slam off Dale Murray that somehow didn’t beat us.

Mike wound up playing for seven different teams in a career that spanned ten seasons, compiling 447 base hits in all, or 447 more than anybody writing or reading this ever has or ever will. His last year, with the Dodgers, came in 1984, or one year before Rusty took his final bow, fortunately in a Mets uniform, with new management having reacquired him five years after the previous regime shipped him to Michigan.

The story of Mike Vail’s Metsian journey, if you venture beyond the ellipsis, tends to curdle (as too many Met stories do), so let’s rewind it to where it was its most delightful. Let’s abide by what was written on Mike’s behalf in the 1976 yearbook, when his 1975 exploits were still fresh in everybody’s recollections…

“Collected more ink and superlatives than any rookie in Met history after reporting from Tidewater.”

I wasn’t baseball-conscious in 1967 when Tom Seaver first dropped by from Jacksonville, but putting aside that possible freshman-sensation omission, yeah, it’s true. Mike Vail came out of the box ready-made and astounding. I was older at the end of the 1975 season than I was at its beginning — a hazard of aging, it seems — but I was still 12. At 12, my analytical approach to the game allowed me to project forward with utmost confidence that if this guy is this good for us now, he’s gonna keep being great for us forever, or for however long he plays for us, which will clearly be for a very long time. I was sure of it. I was sure of Vail.

“It definitely for me has a ‘my favorite year’ quality to it,” Conan O’Brien once said of his experience writing for Saturday Night Live, a program that debuted on October 11, 1975. “I’ll never be that young and naïve again.” In the fall of 1975, I was that young and naïve, and I had years of Mike Vail to look forward to.

In my heart, sometimes, I still am and I still do.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

“Mike wound up playing for seven different teams in a career that spanned ten seasons, compiling 447 base hits in all, or 447 more than anybody writing or reading this ever has or ever will.”

Are you SO SURE not one of has ever collected a hit in the big leagues? You don’t think it’s at all possible that, say, John Olerud didn’t stop by some day? Bob Bailor didn’t google himself and get here? Keith, sent here by a production intern?

Revisions will be made as players with 448 or more career hits confirm their presence,

Hey, I didn’t amass 447 hits either, and tip of the hat to Mike and his career-shaping jump shot, but I am tied on the all-time Mets base hits with Jed Lowrie. You could look it up.

By producing as much for the Mets as Jed Lowrie for far, far less, we are all the new market efficiency.

Nice touch – but I thought the words were, “Brender and Eddie had had it already by the summer of 75”?

Brender is the way I remember Billy Joel singing that line in his best Hicksville.

I’ll go with the lyrics in print, the accent when singing along.

Meh. That Brender was always much too lazy. Eddie could never afford to finance that sort of lavish lifestyle. And the less said about that apartment, the better.

Deep pile carpet.

A couple of paintings from Sears.

A big waterbed.

To each, Brend(er)/Eddie’s own.

Ah, 1975, when I was old enough to begin understanding baseball and too young to know what I was getting myself into with these Mets. Vail, Staiger, Torre, Unser, Frazier…the names still ring out.

And let’s not forget the great Gene Clines, who we got for Duffy Dyer. I thought he was gonna be great. After all, he was a hitter from Pittsburgh. Alas, that was not to be, and I believe they got rid of him right after the season.

Clines was traded to Texas on the very same day Staub was traded to Detroit. The return for Gene was Joe Lovitto, who, after four years with the Rangers, didn’t play at all for the Mets, Tides or anybody else following 1975. He was a lifetime .216 hitter who passed away in 2001 at the age of 50.

I was 10 that season, and any loss was agonizing, but when Vail could not get a hit in that 18 inning game, I think that hurt most of all. I think the game was on the radio only, and I heard every pitch.

First I ever heard of Brock Pemberton was in the Shea parking lot in 1976 while getting Joe Frazier’s autograph before a game. Frazier said Pemberton could really hit, and that we would be seeing him soon. How could you forget a name like that.

R.I.P., Brock.

I’ve hit my toes on that sliding footrest thing that I don’t even know the proper name of that I keep standing around for no good discernible reason AT LEAST 447 times! Does that not count for anything?

[…] Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1971: Tom Seaver 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1974: Tug McGraw 1975: Mike Vail 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1983: Darryl […]