Standard numerical milestone acknowledgements aside, the proper anniversary to fondly recall Gary Carter would have been the 8th. Gary Carter wore 8 and, presumably because he wore 8, cherished 8. Marty Noble told a story about visiting Gary Carter’s house during Spring Training and encountering a keypad in order to enter the property. Noble either forgot or didn’t have the five-digit code, so he guessed. He used 8-8-8-8-8. It didn’t work. Then he used four 8s and one other digit. That unlocked the gate.

In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need an anniversary to do this, certainly not the anniversary of a death, which seems antithetical to the enduring image we maintain of a vibrant and upbeat Gary Carter. We would just find ourselves thinking about Gary Carter because he was Gary Carter and take it from there. Yet here we are, in February of 2022, suddenly 10 years beyond the passing of the last Met to catch the final out of a World Series and, as has been the case since February 16, 2012, we find ourselves missing him.

Gary Carter’s Greatest Hits you can replay in your mind for yourself. This isn’t intended as an exhaustive cataloguing of the biggest blows our Hall of Fame catcher struck, rather a stream of consciousness that just happened to yield 8 things that have stayed with us about Gary Carter, 8 things — ups and downs notwithstanding — we still love about Gary Carter.

1. THE KVELLING BEGINS

As offseason gets go, I don’t know if any get the Mets ever got captivated us the way getting Gary Carter did, particularly when you consider the context. It’s the December after the Mets had upped their season win total from 68 in 1983 to 90 in 1984. We’re still high from having competed vigorously in our first full-fledged pennant race in a baseball generation. We’re convinced we’re momentum-fueled, ready to catch and pass the Cubs in 1985. All we need is…

All we need is Gary Carter! If we didn’t think quite so specifically, we were willing to identify the missing piece once it was delivered to us. We didn’t give up nothing, mind you. We gave up our longtime starting third baseman (turned recent shortstop) Hubie Brooks; our promising rookie backstop Mike Fitzgerald; an outfielder who’d hit .407 in a September callup, Herm Winningham; and one of our many talented pitching prospects, Floyd Youmans. Every one of those fellows would contribute to the Expos, yet the trade was a win for the Mets. Ninety wins plus Gary Carter and assorted other additions equaled CAN’T WAIT! for the next four months.

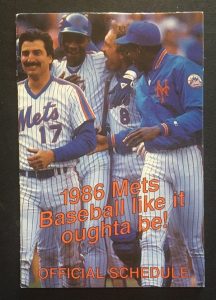

The first season of Gary Carter in New York came exceedingly close to meeting our expectations. The Cardinals replaced the Cubs as our archrivals, and they proved implacable foes, but what a race from Game 1 — which Carter secured with his tenth-inning walkoff home run — to Game 161. Mets fans had never been treated to quite this kind of marathon before, especially those every-fifth-days when it was Gooden pitching to Carter, Hernandez at first and Strawberry in right field. We’d never grouped four players of this nature together at the same time. Now we had them on a regular basis. Them and so many others, but especially them. The Mets grabbed first place early and took it back later, and even if they couldn’t hold on to it all the way to the end, what a ride on this quartet’s collective back it was. No wonder that when we got to Game 162, the only game we entered without a shot at first place, we stood and applauded their season and eagerly craned our necks for a glimpse of 1986.

In 1985, Gary taped his knees, swatted 32 homers, knocked in a hundred runs — right in line with his Canadian exchange rate — and constituted the difference between a team on the come and a team that was just about at its destination. A few smaller pieces would have to be added to make the championship puzzle a perfect fit, but it’s not wrong to consider Carter’s campaign as the pièce de résistance of building blocks once we knew we had something here. You needed a bat like Carter’s to keep climbing in the East. You needed a mitt like Carter’s to catch everything in sight. You needed a storehouse of knowledge like Carter’s to benefit a young pitching staff. Even the slightly older hurlers could benefit. One night in May, he guided Ed Lynch, 29, to his first complete game shutout. Gary being Gary, his instinct was to wrap his arms around his pitcher; Eddie opted for a handshake, as if throwing the best start of his middling career was something he did once a week. “I guess he doesn’t like to give hugs,” Carter said after the game with enough ebullience for the entire battery. “He turned me down. Said, ‘Just shake my hand.’ Eddie’s going low-key on us.”

That wasn’t a key Carter struck too often. Mets baseball itself was a pretty convincing advertisement for Shea’s cast of Rising Stars, yet having a face like Carter’s fronting the franchise couldn’t help but raise everybody’s Q rating. Gary’s smile was made for Madison Avenue as much as his game was ideal for Roosevelt Avenue. We loved Keith, but Hernandez could come off as a little dark. We embraced Darryl, but Strawberry was still getting comfortable as a public figure. Dr. K was ready to pitch in the spotlight more than Dwight Gooden was to have it shine on him. Gary Carter was experienced enough and enthusiastic enough to fill the role of Metropolitan Idol. Call that certain something he brought to New York value-added.

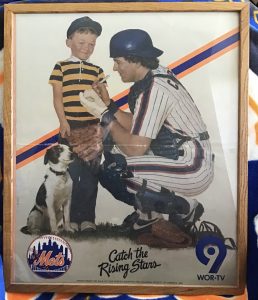

We weren’t yet inside the 1985 season when NBC, on its Sportsworld anthology program, attempted to do its part for famine relief by producing its own version of “We Are The World,” except with athletes standing in for singers. One snippet of one chorus was handled by new teammates Gary Carter and Darryl Strawberry, struggling for literal harmony but singing like they meant it on a practice field in St. Petersburg. We weren’t too far into the 1985 season when Channel 9 began offering a poster featuring catcher Gary Carter as a Norman Rockwell-type character, signing a baseball for a little kid and his dog (probably more for the kid than the dog). It was, I think, five bucks, proceeds going to the Leukemia Society of America; Gary had lost his mom to leukemia. In the moment it took me to wonder whether it was odd that somebody who hadn’t been on team for very long was now its literal poster boy, I sent in my check. Like Mets fans everywhere, I couldn’t live without Gary Carter, in whatever form he was available.

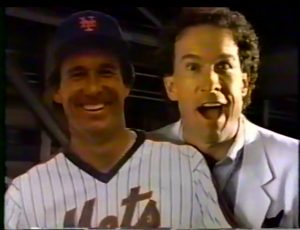

When that almost-made-it of a season was over, I came across the briefest of promos for WOR-TV’s premier property. In the middle of November, when we were all missing the Mets, Channel 9 ran a spot of a man leaning against a pillar in the Times Square station looking like he’s got a case of the Mondays. “Need a lift?” the voiceover asks. “Well, just remember.” The next voice belongs to Ralph Kiner: “Going, going, it is gone, goodbye! A three-run homer…” The image that raises the spirits down in the subway is Gary Carter rounding the bases after going deep off none other than Mike Scott (who, at that moment, was just a random Astro who used to be a Met). Our commuter in the commercial is summarily lifted and so are we. “Thanks for the memories, Mets,” the announcer ends it. We are all in on the gratitude en route to winter 1985-1986 when we close our eyes and think about Gary Carter.

2. HE WANTED TO PUMP US UP

Gary Carter was in favor of cleanliness, as evidenced by his ubiquitous commercials for Ivory Soap. Gary Carter wanted you to be conversant in current events and therefore endorsed the selling of Newsday. And when you had to fill up your tank, for the sake of all that was good and holy, please patronize your local Northville Gasoline retailer, just like Gary Carter does.

Perhaps it’s because Northville was a new name in the market in the latter half of the 1980s that Gary Carter for Northville Gasoline is the Gary Carter endorsement I see in the billboard of my mind. You’d see an off brand of fuel here and there, but you just assumed they were fly-by-night. If you really needed gas, you had Amoco, Mobil, Exxon (previously Esso), Sunoco, Texaco, Gulf…you figured you knew the major players. They were the same players who’d been around more or less forever. Then, out of nowhere, there are Northville stations dotting the Long Island landscape, and if we’re not sure they’re viable, we have Gary Carter confirming that they must be OK or he wouldn’t roll his automobile up to one of their islands.

The only other thing I remember about Northville is that Howard Stern custom-read ads for them every morning for a while, which made for strange implicit bedfellows. Howard knew nothing about sports, nothing about baseball, nothing about the Mets, but somehow Gary Carter grabbed his attention. He’d caught enough of Carter’s celebratory clubhouse testimony as the champagne flew in the fall of 1986 to produce a convincing Gary Carter impression.

The only other thing I remember about Northville is that Howard Stern custom-read ads for them every morning for a while, which made for strange implicit bedfellows. Howard knew nothing about sports, nothing about baseball, nothing about the Mets, but somehow Gary Carter grabbed his attention. He’d caught enough of Carter’s celebratory clubhouse testimony as the champagne flew in the fall of 1986 to produce a convincing Gary Carter impression.

From K-Rock the morning after the World Series had been won, to the best of my recollection:

ROBIN QUIVERS: Is there anybody you want to thank?

STERN AS CARTER: I want to thank Jesus.

ROBIN: Anybody else?

STERN: I want to thank the Easter Bunny.

Howard was always gonna be Howard and Gary was always gonna be Gary, and even if the two never met as far as I know, well, they both swore by Northville Gasoline. They just swore in different manners. It wouldn’t have been New York in 1986 without either of them.

3. WHAT’S THE ‘BIG’ IDEA?

A press invite fell into my hands in August of 1987 for the release of a hot new videocassette: Think Big, a VHS production that would have its coming-out party at Shea Stadium prior to a Mets-Phillies game. Somewhere down the left field line of the Mezzanine concourse, an area was roped off, refreshments were offered and, without fanfare, Gary Carter magically appeared in full uniform. No shin guards, but the pants and the jersey, maybe the cap, if memory serves (it doesn’t always). The PR people didn’t much choreograph his drop-by. He just showed up, dutifully, and a crowd formed around him. I don’t remember if the questions were Think Big-related or standings-related. I was too in awe of the idea that Gary Carter could be bothered to ascend several flights from where he’d soon have business behind the plate and in the six-slot of Davey Johnson’s batting order. Other than filming his street-clothes cameo on a Shea ramp for the Let’s Go Mets music video the previous summer — “go ahead, Doc” — I found it hard to fathom Gary Carter would materialize where regular people gathered. His Think Big co-stars Mookie Wilson and Roger McDowell also made the trip in their game togs, but I spotted Carter before I noticed them, and once you realize you’re standing next to Gary Carter decked out in his Mets uniform, nobody else seems quite so impressive.

Think Big is best described as a motivational tape for kids. In the plot, Gary, Mookie and Roger urged the youngsters to, well, think big. Gary strummed a baseball bat like it was a guitar, approvingly watched from the warning track as a fly ball flew over the outfield fence (it was supposedly hit by one of the kids a few feet away, so it’s not like it added points to one of his pitchers’ ERAs) and dispensed world championship encouragement. “Think about what you’re not doing that you could be doing. ‘Think big’ is like trying to do better than your best,” Kid explains to actual children who are flummoxed by a computer that appears dead-set on ruining baseball…which perhaps indicates how prescient Think Big was.

Think Big is best described as a motivational tape for kids. In the plot, Gary, Mookie and Roger urged the youngsters to, well, think big. Gary strummed a baseball bat like it was a guitar, approvingly watched from the warning track as a fly ball flew over the outfield fence (it was supposedly hit by one of the kids a few feet away, so it’s not like it added points to one of his pitchers’ ERAs) and dispensed world championship encouragement. “Think about what you’re not doing that you could be doing. ‘Think big’ is like trying to do better than your best,” Kid explains to actual children who are flummoxed by a computer that appears dead-set on ruining baseball…which perhaps indicates how prescient Think Big was.

There’s also an unfortunate attempt to mimic Pee-wee Herman. By voice, I mean.

Gary carries his burden of being a good example obligingly here, as he did in most of his off-field appearances. I continually got the sense he took his role-modeling seriously, that if he was going to be a superstar ballplayer, a superstar ballplayer owed it to his fans to be what he thought a superstar ballplayer should be. Superstar ballplayer Gary Carter, therefore, is gonna get those kids thinking big. I can’t help but believe that if Gary Carter had been in Revenge of the Nerds, he would have persuaded his fellow jocks to cool it with the taunting and instead put on a clinic down at the local elementary school.

As an accredited journalist, I received a copy of Think Big upon checking in for the event. I brought it home and watched it with my mother. Or tried to. I gave up about five minutes in. My mother got a huge kick out of it. Also, the Mets won that night, 5-3, with Carter going 1-for-3 with a sac fly and guiding Doc Gooden and McDowell through a combined 10-hitter. So, yeah — think big.

4. YOU DO NOT MESS WITH THIS KID

The Gary Carter we got turned 31 just prior to his Met debut. It probably didn’t occur to us how old that was in catcher years. Gary played like it didn’t occur to him either. With all due respect to Think Big, the greatest video production the Mets ever put together was No Surrender, the 1985 highlight film that ran regularly on SportsChannel during rain delays in 1986. It was so enchanting that I rooted for the tarp to remain on the field for at least half-an-hour just to view it again. No Surrender, which was bowdlerized for music rights reasons once SNY’s Mets Yearbook series got ahold of it, was state-of-the-art for MTV-era sports storytelling. Not only did Tim McCarver narrate and not only did it follow the ’85 Mets chronologically (something grand old team highlight films basically never did), but it packed music-video treatment upon music video treatment, clearance fees be damned.

The falling Cubs are shown “No Mercy” in June by both the surging Mets and Nils Lofgren. Keith Hernandez is “The Warrior,” as in Scandal featuring Patty Smyth. Doc gets Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth”: “What a field day for the heat.” Damn. Gary’s winning sequence was scored by “Messin’ With the Kid,” a Blues Brothers track. Not too on the nose, eh? But what made it sing, beyond the title, was the montage. There’s Gary hitting, there’s Gary smiling, there’s Gary politely but firmly giving an earful to an umpire, but mostly there’s Gary catching the hell out of his position.

Two clips stand out:

1) Carter not only blocking the plate and putting a locomotive of a tag on the Pirates’ Doug Frobel, but then pushing him aside with as forceful a go away, kid, you bother me move as W.C. Fields ever managed. Gary doesn’t have time for Frobel. He’s got to look the runner back to first. The play is from the 18-inning game in late April when Gary’s already dealt with one onrushing runner (George Hendrick) and has innings to go before he sleeps. He may have excited because of what he did as a hitter, but we were reminded that day that we had ourselves a catcher.

2) In early June, the Cardinals are running wild, which is a problem for the National League East in general and the Mets most of all. In the third inning of the opener of a Sunday doubleheader at Shea, Vince Coleman steals third and Willie McGee steals second in one fell swoop. This was when it was often said the only gap in young Dwight Gooden’s arsenal was an ability to keep base thieves honest (because he had so few runners to practice holding). Next thing we knew, a ball was getting away from Carter and Coleman decided to bolt for home. Carter, in “Messin With the Kid,” turns into a deli man who comes out from behind the counter to determine who’s causing all this ruckus. With his chest protector as his apron, Mr. Carter grabs that loose ball and chases Coleman all the way back to third. Almost all the way, because veteran Gary in his equipment runs down swift rookie Vince and tags him out.

Warning to baserunners everywhere: you do not mess with this catcher.

5. THEY LIKE EACH OTHER, THEY REALLY LIKE EACH OTHER

Those Mets of Carter and Hernandez if you were going alphabetically, or those Mets of Hernandez and Carter if you were going chronologically, made you care about them beyond their batting or earned run averages. They dripped with personality and they were covered as competitively as they played. The “media” wasn’t a monolith, but all outlets in those days kept extreme tabs on those Mets. Even the junior media.

One Sunday in the summer of 1985, Kidsday, the Newsday section that you’d think was named for Carter but was specifically geared to and more or less produced by children, featured a Q&A with Keith Hernandez. The celebrity Q&As, as interpreted by my friend Fred, usually went something like this:

Q: How are you?

A: I’m really depressed.

Q: What’s your favorite color?

A: Green.

The only specific I remember from the Hernandez interview was the Kidsday staff asking him who were his best friends on the team. Keith named probably at least half-a-dozen Mets, and then, as if he’d realized he’d committed a faux pas, added something to the effect of “I should probably also mention Gary Carter.”

Despite being well out of the Kidsday demographic, I was relieved to have it confirmed that Keith liked Gary, or at least that Keith thought it important to strongly imply he liked Gary. I already assumed Gary liked Keith, because, given all the commercials he did, I figured Gary liked everything. It was important to me that our Veteran Leaders were in sync. I wasn’t naïve enough to believe everybody always liked everybody on my team, but I wanted to believe it. We’d heard that the Expos had had their fill of Carter, but to me that only revealed a deficiency of character on Montreal’s part.

“Camera Carter,” as far as I was concerned, was left north of the border. When, per Noble, George Foster dug up the derogatory nickname while Gary was “doubled over in pain,” his teammates’ reaction was, in essence, “not cool, George.” Noble, writing for Newsday down the stretch in ’85, conceded some of his New York teammates processed Gary’s style as “a little much,” but they “admire his motivation, effort and ability to play despite injury and pain, to say nothing of his talent.”

The vibe remained valid three years later. After he was traded to Minnesota, Wally Backman submitted to an exit interview with Mike Lupica in the Daily News. This was December 1988, the beginning of the end of an era in Flushing. “Gary’s always gonna be a leader in the sense that guys on the team can look up to him,” Backman said, “the way he carries himself on and off the field. Doesn’t matter if you’re a kid or a veteran. I’ve never heard him say a bad word about anybody. He’s just getting older.”

By then, Hernandez and Carter had served a season as co-captains, a year after only Keith wore the C (a letter neither of them wore once they both shared it). It was pretty clear even to a fan reading the papers and listening to pre- and postgame comments that Carter wasn’t crazy about being initially overlooked in 1987. And in his 1993 autobiography The Gamer, he was still a little sore about it. In the moment, to me, Keith was Keith, and Gary came later, so how could Carter argue with Davey’s decision?

“I think Gary may have been a little taken aback by the fact that it was so blatantly obvious who most of the players looked to for leadership,” Mookie Wilson wrote with Erik Sherman in 2014. “Gary may have been the final piece in making us a championship-caliber team, but Mex was our general.”

Yet even in a situation like that, much as when Gary let it be known between the lines he was a little miffed he wasn’t getting more MVP support in 1986; or when he was dropped out of the high-profile cleanup spot; or when he wasn’t a first-, second- or any-ballot Hall of Famer until the sixth time the BBWAA considered his candidacy, I sort of appreciated No. 8 looking out for No. 1. There was an insecurity to Carter that felt palpable from a distance. Maybe it registered as unseemly for such an acknowledged superstar to worry aloud about these ancillary matters, but it was human. Maybe Gary somehow sensed he wouldn’t be around long enough to appreciate the honors that he was sure should have been coming his way. Maybe he had a touch of Billy Joel’s “Big Man on Mulberry Street” in his soul.

“What if nobody finds out who I am?”

6. LONG-TIME IDOL, FIRST-TIME TARGET

Did Gary Carter found WFAN? Not exactly, but he did position himself squarely within the station’s first batch of content. What is sports talk radio if not a forum for debating whether a hometown player is to be venerated or vilified?

Sports talk radio, which had been around in chunks for years, became institutionalized on July 1, 1987, when 1050 AM switched from country music to a format that sounded too good (or bizarre, depending on your perspective) to be true. WHN became WFAN, and WFAN became the home of saying to others what you might have only been saying to yourself all this time. Previously if sports fans wished to be heard by more than a few people at once, they had to buy a ticket to a stadium and express themselves loudly. That’s what had been going on at Shea in 1987. With the Mets having fallen off the pace of 1986, relatively few were in the mood to venerate the defending world champs.

As Jim Lampley, WFAN’s first-ever host, put it shortly after 3 o’clock that afternoon of July 1, “to read the sports sections of this morning’s New York newspapers, you might’ve thought it was October 1,” given the urgency attached to the pennant race the Mets were huffing and puffing to get themselves back into. Patience was less a virtue than missing in action. Gary Carter, he who hit 24 home runs and drove in a team-record 105 runs for the Mets in the regular season the year before — and he who delivered one enormous swing after another in the postseason that certified all of us as champions in our hearts — was getting booed. Not by everybody, but by a vocal percentage of the Shea Stadium throng. On June 29, two nights before the dawn of WFAN, Gary stepped up to the plate in the bottom of the eleventh. The Mets trailed the first-place Cardinals, 8-7, in a Monday Night Baseball showdown that despite transpiring with more than a half-season to go sure as shootin’ felt must-win.

The bases were loaded. There were two out. The Gary Carter of 1985 and 1986 would have conjured a way to at least tie the game and win the crowd. The Gary Carter of 1987 struck out and lost both. Technically, the Mets lost the game as a team, all of them falling 7½ back of the division lead. But the last guy not making contact tends to grab a ballpark’s attention.

In other words, boooooooo.

Two nights later, on the rainy Wednesday night the FAN took flight, the home crowd tried to work out its feelings toward its catcher. In the third inning, after Carter grounded out and left Tim Teufel standing on third, he was booed some more. In the sixth, Carter homered. That rated cheers — and elicited a half-hearted curtain call response from the feistiest fist-pumper who ever took a bow. In the seventh, Carter homered again. Giving the people what they wanted proved popular. More cheers. A heartier curtain call. In the eighth, up for a third consecutive inning, Carter did not homer. He struck out with runners on the corners, but the Mets by then were ahead by four runs. Chastened, perhaps, the fans who remained late through the rain, stood and applauded him.

Carter’s teammates weren’t happy at how he’d been getting treated prior to the home runs. Hernandez: “I could tell he was obviously hurt by it.” Howard Johnson: “You could it tell it bothered him.” The manager believed the fans were spoiled by success, Kid’s and the club’s. “We all know that now that we’ve demonstrated a certain amount of excellence,” Davey Johnson said, “when we don’t give it to them, they’re going to be unhappy.”

Unhappiness wasn’t Gary Carter’s brand, so he put on the best face possible after the 9-6 must-win win (every win was a must in 1987) he personally powered over the Mets’ gleaming new flagship station. “I’d have to say that’s the first time in my career that’s happened,” Carter said. “It’s a case of, ‘What have you done for me lately?’ They have every right to cheer and boo. What it means more than anything else is that they care.” And that memories in New York could be as long as the average length of a phone call to 1 (800) 635-1050.

7. WHEN THE TENT COMES DOWN

The story coming out of the Mets-Braves game in Atlanta on Monday night, May 1, 1989, was Doc Gooden’s left ankle. The mound was muddy, the footing was treacherous and the worry was about a pitcher who slipped. On July 4, 1985, which famously became July 5, 1985, at Fulton County Stadium, Davey Johnson pulled Gooden under dangerous conditions, lest his ace pitcher in the midst of a historic season go into his windup and wind up with an injury.

Not quite four years later, the Mets were cautious but maybe not abundantly so. The ankle (as well as the rest of the pitcher) was brought to the dugout after its muddy mishap in the seventh inning for taping. Satisfied he was good to go, Johnson sent Gooden back to his office to complete a little more business. Doc finished the seventh, started the eighth, gave way to Roger McDowell and picked up his fifth victory versus no defeats in a 3-1 Mets win.

Doc’s ankle would be of tangible concern in the aftermath of Monday night, but Gooden wouldn’t miss his next turn and his pitching looked more than good enough. To the naked eye, the big story of May 1, 1989, would come and go.

The naked eye had no idea what the big story of May 1, 1989, was. The naked eye had to sift through Baseball-Reference after becoming curious decades later regarding a question that crossed the eye’s mind when mulling the magnificence of a Mets team that featured four tentpoles like it never featured before and would never feature again:

When was the last time the Mets started a lineup that was comprised 4/9ths of The Big Four, a.k.a. Gary Carter, Keith Hernandez, Darryl Strawberry and Doc Gooden?

You just read the answer.

I don’t know if anybody else refers to that specific quartet as The Big Four. I’ve never seen it. I never thought it until a couple of years ago. It fits, though. Kid. Mex. Straw. Doc. If the mid-1980s Mets were the marquee, those were the names above it. They were stars. They were superstars. They were megastars. Keep upping the descriptive ante. By reputation, performance and aura, they’d match it.

The Big Four came to be in a box score sense on April 9, 1985, that most magical of Mets Opening Days, Carter’s first game for New York. Gary had been big in Montreal. A big star with a big following (Rue Gary-Carter graces that city’s thoroughfares today). Maybe he wouldn’t be as big in New York in terms of putting up in-his-prime numbers — and maybe New York was too big for a single individual to dominate — but because he was undeniably big in New York, Gary Carter was about to be bigger than ever. Same for Keith Hernandez, a multitime everything in St. Louis, but a celebrity driving in the clutchest of runs in Queens. As for Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, their limit was the sky when 1985 commenced, and the sky just kept inching higher.

Gary signed with the Mets for five seasons, a time span during which the other components of The Big Four were under contract, so you could say their reign together lasted five seasons. But more granularly, it spanned 79 regular-season games. That’s how many times Davey Johnson submitted a lineup card that was 44.44% covered by…

Hernandez 1B

Strawberry RF (CF a few times)

Carter C

Gooden P

…and, no, wise guy, the rest wasn’t covered by Garry Maddox.

The last time, No. 79, was an occasion that had zero fanfare to it. There was no reason it would. It was barely May. It was a Monday night in Atlanta when a Mets-Braves contest was bereft of inherent hostility. They were in the West. We were in the East. The two clubs hadn’t played a mutually meaningful game since the 1969 playoffs. The schedule called for the Mets to visit Fulton County. The rotation called for Doc to take the ball. The manager didn’t do anything special in writing down Keith’s last name to bat third, Darryl’s to bat fourth and Gary’s to bat seventh. Carter had hit .117 in April, so the seven-spot isn’t as shocking as it might appear if you’re picturing vintage Kid.

Nothing lasting forever probably didn’t need Gary Carter to illustrate its eternal truth, yet the end to something that seemed as if it had just begun was more in sight than we cared to admit heading into 1989. In 1987, he was booed. In 1988, he went three months between home runs, which would have been noteworthy given it was Gary Carter, but turned absolutely painful because the home run that awaited a follow-up was the 299th of Kid’s career and, boy, did he want that 300th. Come the NLCS in ’88, though both Carter and Hernandez each delivered in a couple of key moments, you couldn’t dispute Roger Angell’s assessment, written after the Mets lost the pivotal fifth game en route to losing the series to the Dodgers in seven: “The Mets…looked middle-aged on the field that afternoon and in their clubhouse as well.” At the time, Roger Angell was 68 years old, Carter 34, Hernandez about to turn the same…half of Angell’s longevity to date. The man recognized middle-aged when he saw it. (Roger’s 101 now if that makes you feel any younger.)

When we traded for him, Gary was 30, fluffily curled and coming off one of his best seasons in a career that was stocked with best seasons. For arguably the most significant two-year stretch in franchise history, he was a legitimate differencemaker. You know all those big names the Mets tend to get when the team is at a crossroads and the names proceed to shrink rather than magnify under New York scrutiny? And the crossroads go awry? That wasn’t Carter in 1985 and 1986. He was a new paradigm: the superstar who stayed super helping to lead a good team to monumental greatness. If that’s Gary Carter’s Metropolitan story in toto, that’s fantastic.

It’s not the entire story. The entire story includes a denouement, to put it kindly. The rest of the story, however, despite precipitous statistical declines as he aged past 35, didn’t really dent his Met legacy. Gary Carter in his shrinking-perm stage is no more than ellipsis. Yet if you were there in 1987, 1988 and especially 1989, you couldn’t help but notice Carter’s prime wasn’t what it used to be. But he was still Gary Carter, and now and then there’d be a smattering of success that was straight outta ’85. I can still remember walking into a motel room in Tulsa, Okla., at the end of an August afternoon of business obligations, tossing aside my suit jacket and turning on CNN Headline News to learn that Gary Carter went 4-for-4 in Philadelphia, which tickled me half-a-continent from where I usually got giddy. Any Met going 4-for-4 was good news. Gary entered the day batting .116. That is not a misprint. He ended it batting .152. Also not a misprint. By 1989, you kept wanting to pin numbers like those on erratic typesetting.

Nope, the Mets of Carter and Hernandez and Strawberry and Gooden, even though we hadn’t realized it in May and still didn’t grasp it in August, were over. The next time Gooden pitched after the aforementioned game in Atlanta, Teufel gave Keith a blow at first (a lefty was pitching for Houston). The time after that, Gary’s right knee, unable to bend, was about to nudge him to the DL. Kid had last played May 9. Doc’s next start was May 12. Gooden, throwing to Barry Lyons or Mackey Sasser, went along having a dynamite season until late June, when his right shoulder sent him to the sidelines. Carter was still there. So was Keith, out since the third week in May with a broken right kneecap. Hernandez returned to the lineup on July 13. Carter played again on July 25. Neither was deployed as a regular. Doc’s season, save for a pair of September relief appearances, never regenerated. But he’d be back in 1990. So would Darryl, who skipped the ’89 All-Star Game with a broken toe; honestly, it hadn’t been a very stellar first half for the perennially elected Strawberry.

None of The Big Four was gone altogether from the Mets in 1989, but they no longer composed an elite unit within a juggernaut. It’s not like there hadn’t been a strong bench between 1985 and 1988 should another catcher, first baseman or right fielder have to be called upon; it’s not like the positions that didn’t belong to Carter, Hernandez and Strawberry weren’t manned skillfully; and it’s not like you weren’t getting your innings’ worth out of Darling, Ojeda, Fernandez and so on when Gooden was between starts. But the Big Four was where glamour lived, where excellence thrived, where you most fervently directed your passion.

After May 1, 1989, you never saw it again. Only hair styles can claim to be permanent, and they don’t last either.

Gary’s final turn at bat at Shea as a Met (he somehow willed three more seasons in three more stops from his perpetually barking body) was a thing of beauty, a double struck into the right field corner after he’d taken over behind the plate from Mackey Sasser. He and Keith were permitted last plate appearances in front of what was left of the diehard masses who celebrated their most every move for a few years less than a few years before. Keith’s AB produced a flyout that left his average at .233. Gary’s double raised his to .189. The statistics were hardly the point. The 18,666 in attendance reveled in a proper goodbye.

The Mets, ending their 28th season, had orchestrated few on-field farewells in their history. Maybe when Rusty Staub pinch-hit as 1985’s last batter. Rusty was 41. He probably wasn’t coming back but wouldn’t be definite about it on Closing Day after grounding out on what became the final pitch of his 23-season career. The club held a night for Willie Mays in 1973, and the occasion packed Shea, but (surprise, surprise) M. Donald Grant offered “no support for Willie’s retirement,” according to one of Mays’s advisers, and the planning for what became a star-studded, tear-welling pregame gala was left to Willie’s people. The fans never knew for sure if they were saying goodbye to Seaver or Koosman or Cleon or Buddy as the ’70s unraveled or, for that matter, Mookie or Lenny earlier in 1989. Hell, Joe Torre didn’t find an at-bat for lifetime Met Ed Kranepool in what loomed as Ed Kranepool’s final career home game…on Fan Appreciation Day in 1979.

Carter and Hernandez at least got to tip their caps on the way out and the gesture returned from the stands. They and their deeds had been too big to ignore. Shortly after the schedule played out in Pittsburgh, the co-captains also shared a press conference at Shea. The Mets would be re-signing neither man, but they provided them the space to have their say in the old Jets locker room.

Mex: ”It’s sad because these have been six-and-a-half great years, and I’ll always be a New Yorker and a New York Met. But then come the cold realities. You can’t retire at 65 in baseball.”

Kid: “I can still play this game, and I know there’ll be an opportunity out there. But these have been five great years. I heard the cheers and I heard the boos, and I like the cheers a lot more. Maybe I’ll hear more of them.”

“Privately,” Tom Verducci summed in Newsday, “it was Hernandez who pumped up his teammates and gave the Mets their swagger. but publicly, it was Carter who created the aura of arrogance that the club came to feed on,” an aura that had evaporated as 1989 closed. It was bracing how quickly 1986 had become the past. The Mets had been peeling off their championship players with disturbing alacrity since they let Ray Knight walk and traded Kevin Mitchell to San Diego. With Carter and Hernandez thanked for their service and directed to the exit, the World Series roster of 24 would be almost two-thirds gone by the turn of the decade.

“Somebody will have to lead the Mets into the ’90s,” Keith observed. “And it’s not going to be Gary or me.”

8. FAITH AND KID IN FLUSHING

On December 12, 1984, two days after we discovered who was going to co-lead the Mets for the balance of the ’80s, Gary Carter stood at a podium in the Diamond Club at Shea Stadium and announced, “I’ve saved the ring finger on my right hand for a World Series ring.”

On October 27, 1986, the Mets won the World Series, the last out recorded on a swinging strike three that landed into the mitt of Gary Carter.

On April 7, 1987, Gary Carter was presented with his World Series ring.

On August 12, 2001, the Mets prepared to induct Gary Carter into their Hall of Fame, their first such selection since Keith Hernandez was presented with a sculpted likeness of his own four years earlier. Evocation of 1986 represented a rare bright spot on the premises. Two-Thousand One had been a dreary season to that point. The Mets sat 10½ games out of first place and weren’t a factor in the Wild Card race. They’d recently made three trades subtracting four players — Todd Pratt, Turk Wendell, Dennis Cook and Rick Reed — who had helped them to the postseason in 1999 and 2000. It felt akin to where the Mets had been in 1989, except there was no relatively recent world championship in our rearview mirror. The Mets were still waiting to pick up where they left off when Carter, cradling the sinker Marty Barrett couldn’t touch, embraced Jesse Orosco. It was no wonder that when GM Steve Phillips inserted himself into the Hall festivities, he was vigorously booed. Guest of honor notwithstanding, we were in a bad mood that Sunday afternoon.

Against this sullen backdrop, who could light our world up with his smile? None other than the Kid who made good on a promise of ultimate success once before. I couldn’t see his right finger from where I sat in Mezzanine, but I had to believe it still sported that ring he was determined to win.

Against this sullen backdrop, who could light our world up with his smile? None other than the Kid who made good on a promise of ultimate success once before. I couldn’t see his right finger from where I sat in Mezzanine, but I had to believe it still sported that ring he was determined to win.

“Keep cheering for them,” Carter encouraged us as he pointed to the Mets’ dugout. “They’re gonna win another championship. I guarantee it.”

Since he didn’t specify a date, I’m gonna keep believing in Gary Carter.

Aww, Gary. We miss you. You know, 8 is considered a lucky number in many Asian cultures.

Gary Carter may be my favorite Met ever – both as a player and a man. Thank you for a beautiful tribute. They don’t make ’em like the Kid anymore.

Awesome. This is why I read this site. Allows me insight into history