The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

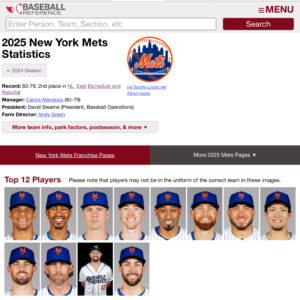

by Greg Prince on 2 December 2025 1:29 pm At any given moment during the baseball season between Opening Day and August 31, there are 780 active players on major league rosters — 30 clubs, each with 26 players. Maybe a few more are scattered about if the 27th Man clause is invoked for a day-night doubleheader or neutral-site contest. On September 1, when rosters expand to 28, the total rises to 840+. Given the steady stream of personnel promotions and corresponding demotions over the course of a campaign, it seems certain that MLB never encompasses the same 780 or 840 players from one day to the next. For example, the team we root for used 63 different players across 162 games in its most recent season, and activated two others who never saw action.

Across the entire 2025 calendar, according to my best reading of Baseball-Reference, well over 1,400 different individuals played in at least one Major League Baseball game. It’s not a snap to suss out an exact figure that doesn’t double-count position players who pitched, or pitchers who might have drifted into the offense portion of box scores through late-inning batting order machinations (let alone whatever handful of pitchers actually did something other than pitch), or players who played for multiple teams. This is not to mention Shohei Ohtani, who is his own category. Without picking apart thirty sets of statistics, I’m confident in asserting there were somewhere between 1,400 and 1,500 ballplayers in the majors last year, probably closer to 1,500.

The exact number isn’t essential, but the point that every player who entered a game at the highest professional stratum of the sport has to be pretty damn good to have done so is. I hark back to Gary Cohen’s response at the press conference preceding his Mets Hall of Fame induction a couple of years ago when I asked what was different about the major league life than he might have imagined when he was aspiring to it.

“Going from being a fan to a broadcaster at the highest level in Major League Baseball, I think the thing that you learn very quickly is what extraordinary athletes these guys are. You know, it’s very easy for people to sit in the stands and watch major league baseball players fail, and it’s a game of failure, but even the last guy on a major league roster is an extraordinarily talented athlete, and just standing behind a batting cage and watching the hand-eye coordination involved, again with the lowliest of major leaguers, is so far beyond the ken of those of us who can’t do those things, I think it makes you appreciate just what this game is, and how difficult it is to play, and how monumentally talented all of these players are. To me, that was the most eye-opening piece.”

Gary said that in 2023, but it’s returned to my consciousness in the wake of 2025, particularly the part about “how monumentally talented all of these players are”. More than 1,400 players, and if they’re not all great, they each can be on this pitch or that swing. If it’s not a wholly level playing field from one team to the next, the difference between competing rosters from day to day is likely smaller than we imagine when we’re making our semi-informed preseason picks.

All of this, rather than what a splendid postseason the Mets had this past year, is in my head because one word kept coming up as the Mets’ chance to keep playing into October slipped away: talent. The Mets, the Mets themselves kept telling us, had too much talent to not make the playoffs. They were too talented to not suddenly rekindle their mysteriously disappeared winning ways. They were too talented to keep reeling off lethal losing streaks. The talent in their clubhouse was too substantial to not coalesce into desired results.

Except it wasn’t. Because everybody’s got talent. Some more than others. Some less than others. Some who it apparently doesn’t matter how much they have, because the talent can’t necessarily be converted to consistent success.

That last cohort includes us. It informs why Faith and Fear in Flushing’s Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2025 — presented to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates, or transcends the year in Metsdom — is Talent’s Limitations. If the Mets didn’t have all the talent in the world, they claimed a copious share of it. And it got them nowhere, or at least not where they and we assumed they’d be once the regular season was over.

Why? Because, again, everybody’s got talent. Maybe not what we would have estimated as Met-level talent when the Mets’ talent was registering win after win as a rule, but enough to stay in a game and pull it out late, or take a lead early and maintain it to the end. The 79-83 Marlins could do that, and did it five out of seven times to the Mets in August and September. The 66-96 Nationals could do that, and did it four out of six times to the Mets in August and September. Seventy-nine times in 2025, somebody beat the Mets, leaving them a defeat too far from an opportunity to continue playing. It was counterintuitive to bet against this ballclub, but maybe that’s why some people yearn to build gambling facilities adjacent to ballparks.

Before the losses added up to one too many, the Mets kept reminding everybody, including themselves, that they were too awesome to fail.

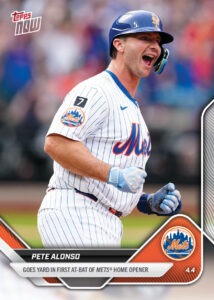

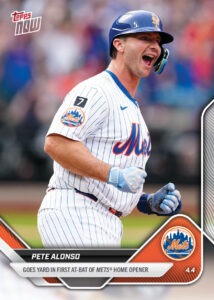

“There’s a lot of belief in this group. There’s a lot of talent in this room.”

—Pete Alonso, June 26, 2025

“We’re not playing well. But [we have] too much talent. We’re going through a very tough time right now, but there’s a lot of good players there. We haven’t played well, but we’re still pretty much right in the thick of things. We gotta find a way.”

—Carlos Mendoza, August 14

“This is the most talented team I’ve ever played on. So I know exactly what we’re capable of. It’s just going out there and executing it every night.”

—Brandon Nimmo (remember him?), August 26

Funny, but nobody ever mentioned how much skill and aptitude had infiltrated the clubhouse.

If only the 2025 Mets could have thrown their reputations or self-regard out onto the field. Instead, it was the 2025 Mets themselves who had to take care of business, which they missed doing. Continual witnessing of their attempts to maintain a division lead, then a Wild Card edge, then a last gasp advised the attentive observer that this team would not reach any of the thresholds required to keep playing beyond Closing Day.

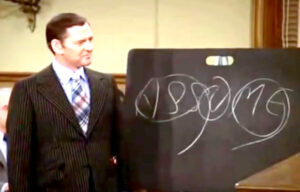

The 2025 Mets, talented as they were, lost seven games in a row in June; seven games in a row spanning late July and early August; and eight games in a row in the heart of September. They had pretty much inverted Val’s big number from A Chorus Line. For looks — on paper — they might have been a 10, yet when it came to performance between the white lines, particularly the dance down the stretch destined to determine their fate, they were more like a 3. I don’t think the second seven-game losing streak was complete before it occurred to me that an admirable aggregation of talent was swell, but not immune to fomenting disappointment in the long run. The talented team must think. The talented team must execute. It’s preferable that the talented team’s players vibe, but as long as they jibe in terms of winning games, cordial working relationships seem sufficient. When the Mets won, they’d all gather into a festive oval and offer a triumphant group kick. I’m not sure if anybody was delivering figurative kicks in the rear after losses. If they were, they weren’t effective.

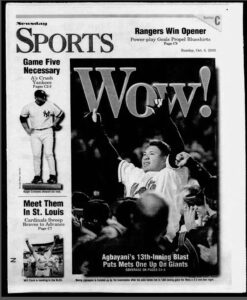

In the 93 games the 2025 Mets played after they peaked at 45-24 on June 12, they went 38-55, a disqualifying enough mark. More damning? In the 71 games when the Mets weren’t going 0-22 amid their three signature skids, their cumulative post-June 12 record ran to a mere 38-33, indicating they weren’t doing so terrific during the bulk of the days when everything wasn’t skidding downhill. As a point of comparison, the 1999 Mets endured losing streaks of eight games at midseason and seven games in the second half of September, enough to smother an ordinary team’s postseason dreams. But Bobby V’s extraordinary troupe negated that 0-15 by posting a 96-51 record the rest of the time, enough to qualify them for the one-game play-in versus the Reds that ultimately earned them a playoff berth (back when each league offered one Wild Card rather than three). That Mets team’s Mojo was irrepressibly Risin’. This one’s sagged and stayed sagged.

Still, I bought into the talent notion as much as any fan.

• I heard myself tell a friend of mine during one of the games that followed the first seven-game losing streak, as we bandied about trade deadline possibilities, “I’m taking postseason as a given.”

• As chronically keeping an eye on the Phillies gave way to tracking the Reds’ trajectory, I couldn’t quite accept the need to redirect my scoreboard-watching, as if monitoring Cincinnati was, honestly, a little beneath us.

• In July, I reluctantly accepted a doctor’s appointment for late October, despite my concern I would be too consumed by what the Mets were likely to be doing to keep it.

• When Reed Garrett returned from the injured list and delivered a shaky September outing, I thought to myself, “I don’t know if he should be on the postseason roster,” as if a postseason roster was sure to be constructed.

• In the euphoria enveloping me in the final minutes of my alma mater’s college football conquest for the ages — USF 18 UF 16 via walkoff field goal on September 6 — I not only clicked away from the Mets-Reds game still in progress (something I rarely do during any Mets game, let alone one with playoff implications), but alerted the gods that if the Bulls can pull off this upset of the Gators in Gainesville, “I don’t even care if the Mets lose tonight”…which the Mets were en route to doing, anyway, at the instant I spoke my sacrilege aloud.

I was fully conscious in the moment that I was willing to give away a Mets game against a team they very much needed to defeat. I also caught onto my other multiple karmic faux pas as I said or thought them. The hardened fan in me knows you don’t assume in advance, in deference to what Felix Unger spelling out what it inevitably makes of you and me. Yet, like Alonso and Mendoza and Nimmo and the rest of those who spoke for the Mets, I deep down believed, nah, we can’t possibly blow this.

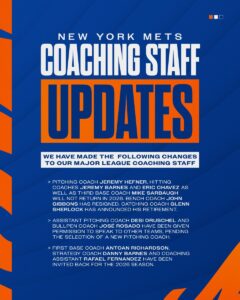

Lesson learned yet again. Then it got blown, and it was somehow not a shock. Nor that much of a surprise. A year earlier, it took me a while to come around to the idea that the 2024 Mets were really good. It took me a little longer a year later to come around to the idea that the 2025 Mets might not be that great, but it did sink in. It didn’t quite make surface-sense that the Mets couldn’t flash their credentials and gain admission to the postseason, but their rotation did keep falling apart; and all those relievers who were supposed to provide relief in relief of their relievers who chronically fell short did fall even harder (here’s hoping the next one won’t); and third base did reinstall its ancient revolving door; and center field did prove an utter sinkhole; and slumps weren’t snapped in a timely fashion; and vapor locks occurred nightly; and other teams got on the field and didn’t care that the Mets had so much talent, unless it motivated those other teams to play a little harder.

I’m not sure if piss & vinegar sentiments akin to “so what if they’ve got Soto and Lindor and Alonso and Diaz and all those hyped guys, they ain’t no better than we are!” are actually expressed among the ranks of professional athletes, but watching the Nationals take four of six from the Mets, and the Marlins take five of seven from the Mets, when we were certain there was NO WAY that should have happened over the final six weeks of the season, maybe the alleged dregs of our division did dig a little deeper, while the Mets dug fairly shallow. As was, the Mets dug their own competitive graves while losing seven in a row, seven in a row again, and eight in a row (independent of those Marlins and Nationals debacles), and they jumped right in. The sub-.500 clubs from Washington and Miami, the ones that didn’t have many or maybe any hyped guys, were absolutely capable of kicking a little more dirt on what was left of the Mets’ hopes, and that they did.

The Mets had all that talent. What did it mean in the end? I don’t know. I doubt any of us does.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS NIKON CAMERA PLAYERS OF THE YEAR

1980: The Magic*

2005: The WFAN broadcast team of Gary Cohen and Howie Rose

2006: Shea Stadium

2007: Uncertainty

2008: The 162-Game Schedule

2009: Two Hands

2010: Realization

2011: Commitment

2012: No-Hitter Nomenclature

2013: Harvey Days

2014: The Dudafly Effect

2015: Precedent — Or The Lack Thereof

2016: The Home Run

2017: The Disabled List

2018: The Last Days of David Wright

2019: Our Kids

2020: Distance (Nikon Mini)

2021: Trajectories

2022: Something Short of Satisfaction

2023: The White Flag

2024: Suspension of Disbelief

*Manufacturers Hanover Trust Player of the Year

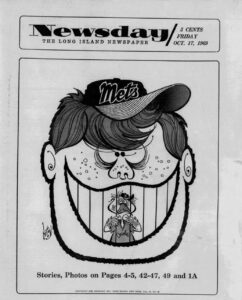

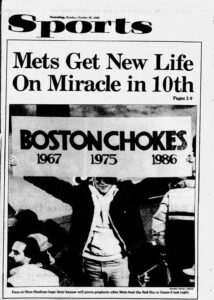

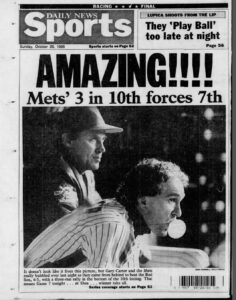

by Greg Prince on 27 November 2025 12:17 pm You may have noticed the New York Mets played no postseason games in 2025. To compensate for our favorite team’s autumnal shortfall, we are happy to have harvested a bushel of postseason Mets games as a coda to the completion of the most recent World Series…even if none of them is from 2025.

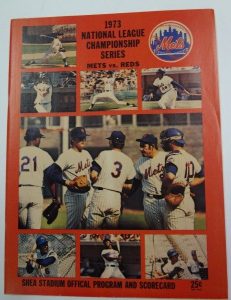

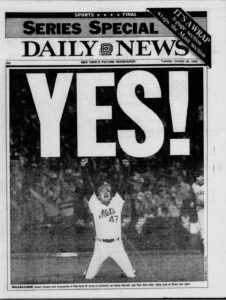

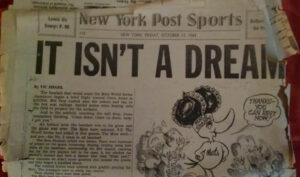

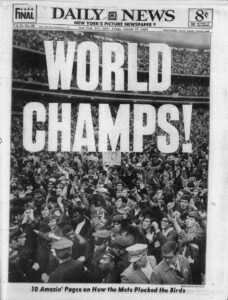

Faith and Fear in Flushing proudly presents an update to its 2020 feature that endeavored to rank EVERY Mets postseason game ever played. At the time of its initial publication, the Mets had participated in nine postseasons and 89 games therein. Five years later, those totals have risen to eleven and 105, respectively. Below we examine every fall festival in which the Mets have partaken and seek to contextualize every Wild Card (1), Wild Card Series (6), League Division Series (20), League Championship Series (49), and World Series (29) game the Mets have played, daring to put them in order, No. 105 to No. 1.

The motivation for such an exercise, as spelled out in 2020 — with numbers revised to reflect current totals:

The Mets have played 105 postseason games, winning 59 and losing 46. When each was played, each was the biggest game of all time to us. That’s how the postseason is when our team is involved. But when we pull back, years and decades following 105 final pitches, not all throb with the same meaning we attached to them as they alighted and unfolded in 1969, 1973, 1986, 1988, 1999, 2000, 2006, 2015, 2016, 2022, and 2024. Some we talk about constantly when we talk about the Mets. Some we think about probably every day since they happened. Some we attribute all kinds of enduring mishegas to even if they were only one game. Some thrust us forward. Some stopped us cold. Some dictated much of what came next. Some are memorialized and revered. Some, somehow, were plowed under by the games and seasons that came next. Each, in one way or another, informs who we are as Mets fans and how we consider the Mets when we consider the Mets…which is what people like us do with as little pause possible.

There’s no statistical formula to this, just loads of paying attention and 105 episodes of revisitation. These rankings are rendered in good faith, sans fear. It’s not a My Favorites list, regardless of the subjectivity inherent. It’s not a Best Games list, exactly, though aesthetics certainly influenced the contemplation. It’s not a wholly YAY METS list, either. Each of the 105 postseason games the Mets have played tells a story to us as Mets fans and to all as baseball fans: the impressions they left, the legends they created, the myths they made, the resonance that resounds, the history that lives on. These are 105 games that explain us and define us, for better and for worse.

The 46 Met losses, unfortunate as it is that they exist, are intermingled here with the 59 Met wins. No harm to any Mets fan’s psyche is intended by being brutally inclusive. Our self-perception, as well as that the world at large has developed of our ballclub, is based largely on these October/November successes and the not-quite-successes. To play in postseason implies success to begin with. Failure may not be an option, but it’s also not the right word to describe any team that gets as far as these eleven Met teams did. Still, sometimes history turned on the games that got away. Or at least seemed as if it did.

The sixteen games that have transpired since the list’s original incarnation have been plugged in where deemed appropriate, naturally affecting the earlier rankings, but none of the games that predate this updating have otherwise exchanged places. A modicum of tweaking to the text has been done for exposition’s and clarity’s sake, but the commentary for the games spanning 1969 to 2016 is mostly the same as it appeared when published in 2020. For the record, the bulk of each of the 2022 and 2024 entries was written in the immediate aftermath of when those games happened, as I figured I’d be revising all this eventually. The sixteen games that have transpired since the list’s original incarnation have been plugged in where deemed appropriate, naturally affecting the earlier rankings, but none of the games that predate this updating have otherwise exchanged places. A modicum of tweaking to the text has been done for exposition’s and clarity’s sake, but the commentary for the games spanning 1969 to 2016 is mostly the same as it appeared when published in 2020. For the record, the bulk of each of the 2022 and 2024 entries was written in the immediate aftermath of when those games happened, as I figured I’d be revising all this eventually.

Eventually has arrived. Here’s hoping more Mets postseason action will follow — and give us something to be thankful for — in the years ahead.

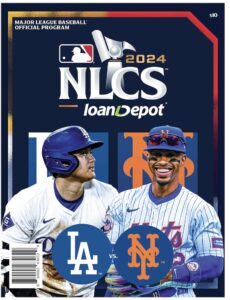

105. OCTOBER 13, 2024 — NLCS Game One: DODGERS 9 Mets 0 105. OCTOBER 13, 2024 — NLCS Game One: DODGERS 9 Mets 0

The concept of “just one game” never loomed larger after the Mets lost by their largest postseason margin to date. Kodai Senga, attempting to build his endurance to three innings, never made it out of the second. The bullpen wasn’t better, the offense was tepid versus Jack Flaherty (Jesse Winker, one of the few Met baserunners, pulled a boner between second and third to kill the closest thing to a rally the Mets mounted all night), and the defense committed a pair of errors. After the game, it was reported Brandon Nimmo was dealing with plantar fascitis, explaining the limp he displayed in the series opener. The whole team limped toward the next day, when the sun rose and the Mets were granted a chance to pull even in their next version of just one game.

104. OCTOBER 16, 2024 — NLCS Game Three: Dodgers 8 METS 0

Temperatures dropped in Flushing as did the probability that the Mets would grab a series lead. If you listened closely, you could almost hear winter clearing its throat. Luis Severino, named a Gold Glove finalist the day before, had trouble with a couple of comebackers, which helped lead to the first two Dodger runs in the second; the Met starter lasted into the fifth and didn’t give up anything else. Meanwhile, Walker Buehler, on the long, hard road back from Tommy John surgery, returned to ace form for four scoreless innings, assisted a bit by the Flushing winds that knocked down what could have been a couple of game-turning longballs. The Dodger pen lived up to its notices, stymieing the Mets offense the rest of the way, as a trio of Dodger sluggers — Kiké Hernandez, Shohei Ohtani (unstoppable with runners in scoring position all postseason) and Max Muncy — went deep off of Met relievers and salted away a whitewashing that looked and felt a lot like the Game One blanking the Mets endured at Chavez Ravine, except it was warmer then and more time remained to shake off such a miserable loss.

103. OCTOBER 17, 2024 — NLCS Game Four: Dodgers 10 METS 2

The Mets matched the Dodgers’ run total, not in the runs category, but rather the number of at-bats they took with runners in scoring position. They came up ten times with a chance to drive in a runner from second and/or third, yet took a collective ohfer. The Dodgers, meanwhile, went 6-for-15 in the same category, and that was pretty much all she wrote as L.A. moved to within one game of a World Series berth and New York trudged closer to putting a great deal of postseason merchandise on remainder.

102. OCTOBER 14, 2000 — NLCS Game Three: Cardinals 8 METS 2

The weather was great, with temperatures peaking in the high seventies. The Mets came in with all the momentum inherent in a two-nil series lead. Then they were clobbered. Rick Reed threw his only bad postseason start. The Mets’ only two runs scored on double play groundouts. Yet when it was over, the Mets still maintained their momentum, with two more home games directly in front of them. It made for a sunny forecast.

101. OCTOBER 6, 1999 — NLDS Game Two: DIAMONDBACKS 7 Mets 1

Adrenaline carried the Mets through four absolute must-win games over Pittsburgh and Cincinnati to get them into the playoffs and propelled them high above Randy Johnson & Co. to grab a series lead once they landed in Arizona. They likely needed a breather. Versus Todd Stottlemyre and the Snakes, they took a nap.

100. OCTOBER 4, 2000 — NLDS Game One: GIANTS 5 Mets 1 100. OCTOBER 4, 2000 — NLDS Game One: GIANTS 5 Mets 1

This one played to the form expected in some circles. The top-seeded Giants jumped on the Wild Card Mets to stake themselves to an early advantage. Past World Series MVP Livàn Hernandez handled the Mets with ease. Derek Bell sustained an ankle injury that ended his postseason. By the time this NLDS was done, Hernandez’s mastery and Bell’s absence would barely be footnotes.

99. OCTOBER 15, 2006 — NLCS Game Four: Mets 12 CARDINALS 5

Oliver Perez made his first postseason start. David Wright hit his first postseason home run. Carlos Beltran went deep twice. The Mets set a franchise record (since bettered) for most runs in a postseason game. Most importantly, they evened a series that threatened to get away from them. And nobody ever brings any of it up.

98. OCTOBER 20, 2015 — NLCS Game Three: Mets 5 CUBS 2

How about that time Jorge Soler fell down in right and allowed Wilmer Flores’s ball to roll all the way to the wall, letting Wilmer scoot to third and scoring Michael Conforto all the way from first, extending the Mets’ sixth-inning lead to 4-2? If you remember that, it’s your mind playing tricks on you, or perhaps you stepped away while the ball was deemed to be stuck under the ivy. The potentially highly memorable moment was downgraded to a ground rule double, sending Conforto back to third. Neither baserunner scored and Jacob deGrom got back to silencing the Cubs regardless.

97. OCTOBER 5, 2006 — NLDS Game Two: METS 4 Dodgers 1

96. OCTOBER 12, 2006 — NLCS Game One: METS 2 Cardinals 0

Tom Glavine’s finest moments as a Met, so fine we have opted for the spelling by which he was identified prior to 9/30/2007. Six innings to chill the Dodgers one Thursday. Seven innings to ice the Cardinals one Thursday later. Shea Stadium roared in support of its lefty ace twice. This really happened, less than a year before Tom Glavine became T#m Gl@v!ne.

95. OCTOBER 2, 2024 — NLWCS Game Two: BREWERS 5 Mets 3 95. OCTOBER 2, 2024 — NLWCS Game Two: BREWERS 5 Mets 3

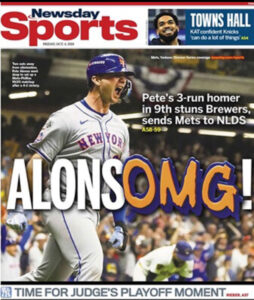

“Six outs away” loomed as the stuff of regretful legend when Phil Maton allowed three eighth-inning runs on two home runs to turn a tenuous 3-2 Mets lead into a crushing 5-3 deficit and grant the Brewers all the momentum in the world or at least Wisconsin. So close to clinching a trip to the next round, so far from actually sealing the deal. Would a night when the Mets stopped scoring after the second and left nine runners on base come back to haunt them? Only the Polar Bear knew for sure, and he wouldn’t reveal the answer until late in Game Three.

94. OCTOBER 8, 1999 — NLDS Game Three: METS 9 Diamondbacks 2

Shea’s first postseason action in eleven years was destined to be overshadowed by Shea’s next postseason action the following afternoon. This Friday night featured Todd Pratt’s first postseason start, which itself was overshadowed by the reason Tank was starting, namely the unavailability of the usual starting catcher, Mike Piazza. For the record, Pratt walked twice and scored a run. It wasn’t Pratt’s finest hour (that would come in less than 24 hours).

93. OCTOBER 14, 2006 — NLCS Game Three: CARDINALS 5 Mets 0

It deserves to be remembered parochially as the Darren Oliver Game, so named for the six innings of scoreless relief the ageless lefty gave Willie Randolph from the second through the seventh. If it’s remembered at all, it’s for the five runs Steve Trachsel gave up in the first. Really, it’s not remembered much.

92. OCTOBER 28, 2015 — WS Game Two: ROYALS 7 Mets 1

Jacob deGrom was on his way to emerging as one of the premier starter of his generation, yet his first (and thus far only) World Series start is the most obscure game among five his team played in their most recent and perhaps most star-crossed Fall Classic.

91. OCTOBER 17, 2006 — NLCS Game Five: CARDINALS 4 Mets 2

Game Five in a seven-game series is either decisive or pivotal. In hindsight, this one was both, backing the Mets to a wall from which they would never effectively detach. Yet this particular T#m Gl@v!ne disappointment (4 IP, 7 H, 3 BB, 3 ER) escapes collective memory, while Jeff Weaver (6 IP, 6 H, 2 BB, 2 ER) is rarely berated in the realm of opposition villainy.

90. OCTOBER 18, 2015 — NLCS Game Two: METS 4 Cubs 1 90. OCTOBER 18, 2015 — NLCS Game Two: METS 4 Cubs 1

The set of contests that determined where the 2015 National League pennant would fly has settled in memory into a blur of Daniel Murphy home runs. This game definitely featured one of those.

89. OCTOBER 1, 2024 — NLWCS Game One: Mets 8 BREWERS 4

The designated hitter rule represented blasphemy to hardcore National League types from the moment the American League adopted it in 1973. In real baseball, pitchers hit for themselves, never more gloriously than on May 7, 2016, when Bartolo Colon, nearing the age of 43, socked the first home run of his career. If Bart was no longer an automatic out, no pitcher should ever be considered one again. Alas, alleged progress’s encroachment on authenticity proved unstoppable. When the DH infiltrated the NL to stay in 2022, rock-ribbed traditionalist Mets fans couldn’t help but grimace that their beloved senior circuit had given in to this passing fad. They probably also noticed the Mets were having a hard time making use of the innovation intended to generate offense. In the wake of an era when the Mets had pitchers who were capable hitters (not just Colon, but the likes of Syndergaard, Matz, Harvey, Wheeler and the still extant deGrom), the 2022 Mets went to the playoffs with two designated hitters — Daniel Vogelbach and Darin Ruf — and received exactly no hits from them.

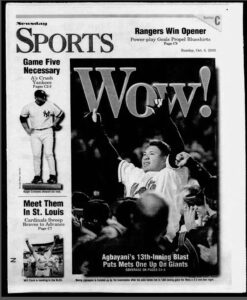

In 2024, with a club that had just stormed into the postseason under the banner of actual Grimace, the existence of the DH within their own domain wound up giving Mets fans a reason to briefly smile without scorn for what commissioner Rob Manfred had done to further destroy the integrity of their beautiful game. In the second inning of the Wild Card Series opener, DH Jesse Winker slashed a two-run triple off Brewer ace Freddy Peralta to pull the Mets into a 2-2 tie (cameras captured fierce jawing between Winker and former teammate Willy Adames on Winker’s route from second base to third, likely another outgrowth of Jesse being Jesse and not everybody loving him the way Mets fans had come to). In the fifth, responding to a Milwaukee pitching change, Carlos Mendoza opted to pinch-hit J.D. Martinez for Winker with the bases loaded, the usual fulltime DH subbing for a DH who sometimes played the outfield. Neither Met had been as much as lukewarm most of September — Martinez challenged the Mets’ franchise ohfer record by going hitless in 36 consecutive at-bats — but October was here, and so was J.D.’s long-proven ability to drive runners home. He smacked a two-run single to right to provide an 8-4 lead for Luis Severino, a starter who had struggled early in the game, but was still on in part because National League managers no longer had to think about pinch-hitting for their pitchers. The Mets wouldn’t do any more hitting on the night, but Severino, Jose Butto and Ryne Stanek combined to put down the final 15 Brewer batters in order, allowing the Mets to be designated winners.

88. OCTOBER 13, 1999 — NLCS Game Two: BRAVES 4 Mets 3

87. OCTOBER 12, 1999 — NLCS Game One: BRAVES 4 Mets 2

Setbacks at Turner Field, even in October, all looked alike for a dismal spell there in the late ’90s. The second showdown in Atlanta sticks out a little more than the first thanks to it including Melvin Mora’s first major league home run (and, if one wishes to be Metsochistic, the loss going to Kenny Rogers).

86. OCTOBER 8, 2022 — NLWCS Game Two: METS 7 Padres 3

The status of deGOAT was at least a little in question. Jacob deGrom was the consensus pick as premier pitcher on the planet from 2018 to the middle of 2021, ascending from the flowing-locks comer he’d been when he helped the Mets to the 2015 pennant to a superhuman league of his own. Unfortunately, while deGrom cut his hair and gained cachet, the Mets mostly lost, whether he pitched or not. Then Jake missed the second half of ’21 and the first four months of ’22 with injuries. When he returned to action, the team was doing wonderfully and Jacob picked up where he left off…for a while. By late September, the Mets’ stumble from undisputed occupancy of first place coincided with deGrom’s disturbing bouts of fallibility. Now the ball was in his right hand to keep the Mets alive versus the Padre — and, if business turned out to be business, perhaps it would be the final time he’d pitch before Citi Field fans as the home starter. Jake had made clear he’d exercise the opt-out in his contract, and after that, who knew what his free agent future foretold?

The present was priority, though, and for six innings, deGrom was as deGOAT as he needed to be, snuffing San Diego threats across six innings, limiting the opposition to two runs, striking out eight and leaving with a 3-2 lead. The Met offense, rarely Jacob’s biggest supporter, not only put him ahead on Francisco Lindor and Pete Alonso home runs, but provided the relievers who followed him with a plush cushion manufactured via a best-case 2022 Mets kind of rally in the seventh, grinding two ten-pitch walks to set up four additional runs. The Mets stayed alive and deGrom stayed a Met, each preserving those precious statuses for another day.

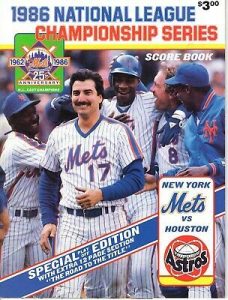

85. OCTOBER 9, 1986 — NLCS Game Two: Mets 5 ASTROS 1 85. OCTOBER 9, 1986 — NLCS Game Two: Mets 5 ASTROS 1

In the fifth inning, Nolan Ryan knocked down Lenny Dykstra. Lenny Dykstra got up and singled off Nolan Ryan. Lenny Dykstra would score after Wally Backman singled and Keith Hernandez tripled off Nolan Ryan. Immortals. Legends. Characters. Drama! And together the whole thing usually rates, at most, a paragraph in retellings of this sizzling series.

84. OCTOBER 12, 1986 — NLCS Game Four: ASTROS 3 Mets 1

The yellow highlighter of the 1986 NLCS. It made sure you would remember “Scott” was crucial in knowing what to study for in preparing for the big test.

83. OCTOBER 23, 1986 — WS Game Five: RED SOX 4 Mets 2

Roger Angell was impressed by this one because it was Fenway Park’s last chance to exude enthusiasm for the year; “less than a classic, perhaps, but there was spirit and pleasure to it.” Surely there were also visiting-team charms to be derived from it, as Tim Teufel homered and doubled in the Mets’ only runs, and Sid Fernandez turned in four foreshadowy innings from the pen, but any footprints Game Five left behind were about to be stomped out but good.

82. OCTOBER 15, 1999 — NLCS Game Three: Braves 1 METS 0

Gl@v!ne outpitches Leiter. Rocker taunts the howling masses. The Mets face elimination. A series that appears to be out of breath gasps ahead of its second wind.

81. OCTOBER 12, 2000 — NLCS Game Two: Mets 6 CARDINALS 5

Close, back-and-forth, see-saw affair, with the Mets eking out a lead in the top of the ninth and Armando Benitez holding tight to it for a commanding series lead. The Mets couldn’t do any better in terms of results, but for an outfit that does postseason drama as a matter of course, it doesn’t particularly pop.

80. OCTOBER 13, 2015 — NLDS Game Four: Dodgers 3 METS 1 80. OCTOBER 13, 2015 — NLDS Game Four: Dodgers 3 METS 1

Clayton Kershaw picks this opportunity to shed his postseason reputation for not-so-hotness, keeping the Mets from clinching a series at home, but in defeat, Daniel Murphy makes it a night to begin a historic streak to remember.

79. OCTOBER 6, 2024 — NLDS Game Two: PHILLIES 7 Mets 6

The good news: four Met home runs, including two from Mark Vientos, one of which tied the game in the ninth. The bad news: Bryce Harper and Nick Castellanos combined for two homers in the sixth, erasing a 3-0 Mets lead, with Castellanos coming through again in the bottom of the ninth with the game-winning hit off Tylor Megill (a tired Edwin Diaz had already contributed his part in the seventh for better and the eighth for worse). The consolation: the Mets could finally return to Citi Field and look forward to playing a home game after two weeks, regular season and postseason, on the road.

78. OCTOBER 8, 2024 — NLDS Game Three: METS 7 Phillies 2

The MTA sent a Grimace train out to the Mets-Willets Point stop, and don’t think fans didn’t light up when their lucky charm stepped out of one of the cars. The co-branding exercise between the ballclub and the fast food franchise for whom the big purple blob usually pitches was part of the Met kismet all summer long. Fall had at last arrived at Citi Field in the form of postseason baseball, so all the talismans were out in force. You could wave your OMG signs, you could clutch your playoff pumpkins, you could be one of the 44,000-plus screaming your head off, but mostly you could watch Pete Alonso and Jesse Winker go deep; Starling Marte and Jose Iglesias be clutch; Tyrone Taylor and Mark Vientos nab baserunners; and Sean Manaea shut down the imposing Phillie lineup for 7+ innings. When it was over, the Mets — who’d been on the road for two weeks — were one game from an opportunity to clinch at home, a home that in October there was no place like.

77. OCTOBER 11, 1988 — NLCS Game Six: Mets 5 DODGERS 1

76. OCTOBER 18, 2006 — NLCS Game Six: METS 4 Cardinals 2

October’s Mets are known to their fans for the splendor of their Game Six efforts. These were indeed splendid, yet they’re not nearly so well known, their residue vacuumed up as they were by the Game Seven results to follow. Still, let us appreciate David Cone (CG five-hitter) and Jose Reyes (leadoff HR; 3 H; 2 R) carrying the Mets to necessary ties eighteen years apart.

75. OCTOBER 7, 2022 — NLWCS Game One: Padres 7 METS 1 75. OCTOBER 7, 2022 — NLWCS Game One: Padres 7 METS 1

The great Max Scherzer was hired at significant expense ($130 million over three seasons) for this moment. The great Max Scherzer didn’t show up. Somebody wearing his uniform took the mound for the New York Mets’ first postseason game in six years, yet it’s almost unfathomable to connect the SCHERZER 21 credited with culturally transforming the Mets into a powerhouse to the SCHERZER 21 who surrendered four home runs — seven earned runs in all — before being removed to home crowd boos in the fifth inning. Were there lingering effects from the oblique injury that twice sidelined Scherzer during an otherwise triumphant 2022? Were there simple mechanical issues that Max might have adjusted had another start awaited him a few days later? Was age catching up to the 38-year-old lock Hall of Famer? Did it matter once the Mets found themselves down, 7-0, to perennial tormentor Yu Darvish? The Mets were playing in this new Wild Card round because the NL East title that would have ensured them a bye to the League Division Series slipped away in a showdown at Atlanta late in the regular season, and Scherzer hadn’t been particularly great in that battle, either. “It’s baseball,” the club’s co-ace said later. “You get punched in the face. It doesn’t matter who you are.” Mets fans nursing an ice pack against their collective jaw after falling behind in the best-of-three set were in no position to argue.

74. OCTOBER 20, 2024 — NLCS Game Six: DODGERS 10 Mets 5

Starter Sean Manaea (2+ IP, 6 H, 2 BB, 5 ER) didn’t have it. Half among the six relievers who Carlos Mendoza called upon after dismissing Manaea in the third didn’t have it, either. Seven of nine Met batters who batted with runners on base didn’t have what it took on their end. Thirteen Met baserunners looked longingly at home plate but did not cross it. The Dodgers, MLB’s “it” team had it all, or at least the National League pennant by night’s end. L.A.’s blend of superstars, simply stars and requisite October surprise personnel — heretofore unsung shortstop Tommy Edman won NLCS MVP honors — combined with a solid enough bullpen to run out the clock on New York’s Cinderella story. Pete Alonso’s good-luck playoff pumpkin was last seen “settled at the bottom of a blue trash can in the visitors clubhouse at Dodger Stadium,” per Tim Britton of The Athletic, right where you might have found any of Mendoza’s preliminary plans to piece together another desperate pitching strategy for Game Seven. In the Mets’ four losses, their well-worn arms gave up 39 runs…and their first baseman one talisman gourd. But OMG, the team of memes itself never gave up. They just didn’t have quite enough to battle all the way to the World Series. Mets fans could hold their heads high in the aftermath of the year’s final loss, though could certainly be forgiven if all they could manage the morning after was one dour grimace.

73. OCTOBER 18, 1973 — WS Game Five: METS 2 A’s 0

Little is more Metsian than Jerry Koosman coming through in the postseason. Nothing is more Metsian than Tug McGraw slamming his glove to his thigh upon closing out a win. Together, the legendary lefties crafted a most Metsian shutout and pushed their club to the brink of a world championship.

72. OCTOBER 17, 2015 — NLCS Game One: METS 4 Cubs 2

Harvey outpitches Lester. Murphy goes deep. D’Arnaud dents the Apple. Mets never trail. After seven losses to the Cubs in seven regular-season contests, the tone between the two teams is reset.

71. OCTOBER 7, 2006 — NLDS Game Three: Mets 9 DODGERS 5

The previous instance in which Greg Maddux started a postseason game against the Mets, Game Five of the ’99 NLCS, day turned to night, the innings totaled fifteen, a fair ball that left the park was ruled something less than a home run and, when it was all over, Atlanta’s lock future Hall of Famer was demoted to an afterthought no more obvious to the outcome than his New York counterpart, Masato Yoshii. The forty-year-old Maddux of 2006 who threw only four innings in what loomed as the Division Series finale might have no longer been the Cy Young-in-residence of the 1990s, but it was still gratifying to watch the Mets outlast an old nemesis. Between withstanding Maddux and sweeping the Dodgers, this game should probably stand out more in Mets lore. It didn’t necessarily stand out in that night’s scores, because the Mets advanced on the same day that the Yankees were eliminated in their ALDS, their dismissal a bigger New York story in the moment. To be fair, watching the Yankees exit, no matter that they stole some Metsian spotlight (and weren’t what they used to be, either), was also pretty gratifying. Or as Manny Acta and Jose Reyes said in call & response fashion in the postgame celebration out west, “Party in Queens, entierro in the Bronx.” Entierro, not incidentally, is Español for burial.

70. OCTOBER 8, 1988 — NLCS Game Three: METS 8 Dodgers 4 70. OCTOBER 8, 1988 — NLCS Game Three: METS 8 Dodgers 4

69. OCTOBER 17, 1973 — WS Game Four: METS 6 A’s 1

It was the heat of the moment that defined a couple of frigid dates at Shea. In the moment, the heat got intensely hot. The controversy of 1988 involved Dodgers closer Jay Howell going to his glove for pine tar, which earned him a suspension from National League president Bart Giamatti. While L.A. argued the punishment did not fit the crime, the Mets emerged in the frozen muck of Flushing with the go-ahead game that seemed to swing momentum New York’s way. Fifteen years before, the man in the spotlight within a Series of legitimate stars was backup A’s infielder Mike Andrews, a pawn amid Charlie Finley’s ever-shifting manipulations. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn wouldn’t let Finley officially scapegoat Andrews, whose fielding had contributed to the A’s loss in Game Two, off Oakland’s active roster, so when Mike came up to pinch-hit in a game the Mets had well in hand (sore-shouldered Rusty Staub homered and drove in five), he was accorded a standing ovation by righteous Mets fans. Good sportsmanship, however it arrived, was by no means dead in Queens.

68. OCTOBER 5, 2024 — NLDS Game One: Mets 6 PHILLIES 2

If it was a day that ended in a “y” this particular week, there was an excellent chance that day included a five-run inning for the Mets. The same offense that crossed the plate five times in the eighth in Atlanta in service to clinching a playoff spot the previous Monday and put up a five-spot on the Brewers in the fifth on Tuesday revved up late at Philadelphia during this Saturday series opener. Their engines were silent for seven innings against Old Friend™ Zack Wheeler, but it was nothing but noise from the Mets bats when the Philly bullpen got involved. From down, 1-0, they rose to lead, 5-1, and looked every part the team of destiNY.

67. OCTOBER 18, 1986 — WS Game One: Red Sox 1 METS 0

66. OCTOBER 13, 1973 — WS Game One: A’S 2 Mets 1

Was this any way to start a World Series? In either case, no way. In both cases, the images that lingered were that of Met second basemen who couldn’t pick up simple ground balls: Felix Millan in ’73, Tim Teufel in ’86. Each E-4 led to an opposition run that made all the difference in getting off on the right foot versus shooting themselves in it. It was just one game twice…but a one-game deficit ASAP.

65. OCTOBER 18, 2024 — NLCS Game Five: METS 12 Dodgers 6 65. OCTOBER 18, 2024 — NLCS Game Five: METS 12 Dodgers 6

Down three games to one, the Mets weren’t too proud to beg for anything to change their luck — in this case, enlisting the Temptations to come to the ballpark before first pitch and lead the fans in singing “My Girl” all together, as had become custom ahead of every Francisco Lindor at-bat, anyway. Yes, the Mets had their backs to the wall, but on this night, backs to the wall meant the wall was in trouble once the Mets got going on this latest postseason do-or-die mission. The way this team did the things it did, that meant that with two runners on in the first inning, Pete Alonso put a ball well over Citi Field’s fence, and several of his teammates went on to assault said barrier with extra-base hits that sent the Dodgers scurrying in the direction of the deepest reaches of Flushing’s outfield. Four doubles, including three from Starling Marte. Two triples. Tons of what Carlos Mendoza reflexively labeled “traffic” on the bases (despite the Mets’ admonition to fans that they should use mass transit), with not a single Met batter striking out. All of it gave Mets pitching — starting with David Peterson for three-and-two-thirds and continuing through the yeoman efforts of Reed Garrett and Ryne Stanek and concluding with two shutdown frames from Edwin Diaz — plenty of cushion against an L.A. attack that had filleted Met starters and relievers alike the previous two nights. One borough over from where John Travolta strutted to keep pace with the Bee Gees, the Mets were stayin’ alive.

64. OCTOBER 9, 2022 — NLWCS Game Three: Padres 6 METS 0

Two ears. One hit. No chance. Joe Musgrove’s spin rate was so beguiling that by the sixth inning, Buck Showalter felt compelled to ask the umpires to check the Padres’ starter for suspect substances. Not in his glove, but behind his ears. Social media was alive with closeups of something shiny beneath the righty’s cap. The umps had a look and a feel. They were satisfied that nothing shady was hidden back there. Musgrove resumed his utter domination of the punchless Mets through seven. Pete Alonso’s single to lead off the fifth and Starling Marte’s base on balls in the seventh constituted the entirety of the Mets’ offense, an entity completely stymied by a pair of Padre relievers in the eighth and ninth in front of a not exactly packed house at Citi Field. Meanwhile, Chris Bassitt and several Met penmen succumbed to the Padres’ unrelenting attack, led by unlikely postseason hero Trent Grisham, who batted .500 from the eight-hole in his club’s three-game series victory. But “unlikely” and “postseason” always seem to know how to find one another.

The dozen wins that separated the 101-61 Mets from the 89-73 Pads in the regular season evaporated, much as the 10½-game lead the Mets held on the Braves at the beginning of June had. San Diego would be in the League Division Series round, thanks to beating the Mets, and they’d go on to upset the even more statistically imposing Los Angeles Dodgers (111-51). Atlanta would be there, too, thanks to a bye earned in large part from their beating the Mets, yet the Braves would go on to be upset by the least statistically impressive team in these NL playoffs, sixth-seeded 87-75 Philadelphia, a club that, oh by the way, was beaten fourteen of nineteen by the suddenly eliminated Mets between April and August. Alas, this was October, and the 2022 Mets, despite totaling the second-most wins in their history during the year — and despite claiming the exact same 162-game record as the division champion Braves (losing the East on a head-to-head tiebreaker) — would be idle until Spring Training, thanks to an early fall you couldn’t have foreseen amid the heights of summer.

63. OCTOBER 24, 2000 — WS Game Three: METS 4 Yankees 2

Lost amid the epic frustration of four losses that each stick in the craw for its own specific reason is the one Met win of the 2000 Fall Classic. It oughta be the other way around given all the compelling elements: Rick Reed strikes out eight in six; Robin Ventura homers; Todd Zeile doubles in the tying run; Benny Agbayani chases the heretofore indomitable El Duque; Brooklyn’s own John Franco gets the win; Armando Benitez, whose allergies clearly included October, garners the first Met World Series save since Jesse Orosco. And the Mets beat the Yankees! What more could a Mets fans want from a Subway Series? Three games more like it.

62. OCTOBER 10, 1988 — NLCS Game Five: Dodgers 7 METS 4

It was supposed to be a travel day. In a sense it was, as the Mets seemed to stand in the terminal waving goodbye to their chances to make their second World Series in three years. Rain the previous Friday forced the series into a Monday makeup barely enough hours removed from Sunday night’s twelfth-inning conclusion to have sleep rubbed from the home team’s eyes. The Dodgers, on the other hand, were all adrenaline, taking a 6-0 lead by the fifth. The Mets’ last best hope was snuffed in the bottom of the eighth when wunderkind Gregg Jefferies got himself called out by running into a batted ball. Shea mostly cheering an injury to Kirk Gibson turned karma in the same direction as momentum — against the Mets.

61. OCTOBER 14, 2024 — NLCS Game Two: METS 7 Dodgers 3

Who’d want to face Francisco Lindor when a home run could do you real harm? The Dodgers probably weren’t thinking this way when this game began, but maybe they should have. Opener Ryan Brasier pitched to Francisco and the resulting leadoff blast instantly reversed the momentum from the Dodgers’ whitewashing of the Mets the night before. An inning later, with the Mets now up by two, the Los Angelenos had to make a decision: try their luck with Lindor again with runners on second and third, or intentionally walk the East Coast MVP and load the bases for Mark Vientos. The shortstop had already burned them, so it was decided the best chance to avert further charring was pitching to the third baseman. As Vientos put it after the game, “I took it personal.” He also took the pitch he got from Landon Knack and deposited it into the right field stands to extend the Mets’ lead to 6-0. Sean Manaea and three relievers bent a little later, but it was the Mets who broke away from L.A. with what they wanted — a split of two games with the National League’s one-seed and a happy flight home to New York.

60. OCTOBER 5, 1969 — NLCS Game Two: Mets 11 BRAVES 6 60. OCTOBER 5, 1969 — NLCS Game Two: Mets 11 BRAVES 6

59. OCTOBER 4, 1969 — NLCS Game One: Mets 9 BRAVES 5

Silly Mets thought they could get by on their sparkling young pitching and anemic offense. Sagacious Braves would teach Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman about the pressure of October. Sure enough, neither of the aces who combined to record 42 wins in ’69 could escape the hammer of Hank Aaron and his Atlanta accomplices. Maybe taking down the champions of the Western Division was going to take more than a couple of talented arms. So the Mets brought more. Lots more. Twenty runs, divided almost evenly, carried the weekend and launched the Mets from the Launching Pad and toward a pennant (Art Shamsky alone had six hits). Seems it was the Braves who were taught a lesson, namely that when you get to October and face the Mets, expect the unexpected.

58. OCTOBER 13, 2006 — NLCS Game Two: Cardinals 9 METS 6

The Mets led the series, 1-0. They led the Cardinals at various junctures of Game Two by scores of 3-0, 4-2 and 6-4. They were using home field advantage to its fullest force. Then the Mets’ bullpen got a little too involved. Guillermo Mota, until Game Two a savvy pickup, imploded. Billy Wagner, most of 2006 a brilliant closer, did much the same. Throw in some shoddy outfield defense from Shawn Green and a little too much pluck and spunk from the likes of Scott Spiezio and So Taguchi, and, well, leads proved to be precarious things.

57. OCTOBER 5, 1988 — NLCS Game Two: DODGERS 6 Mets 3

Come and listen to a story by a man named Cone

Twenty-game winner couldn’t leave an edge alone

Before Game Two in his column with his ghost

Wrote himself some words that perturbed his playoff host

Tattooed he was

Vengeful style

Next thing you know David Cone is oh-and-one

Having a byline wasn’t any fun

Said, ‘Hey, Bob Klapisch — this column ain’t for me’

The Mets hopped on their flight, all tied for Game Three

56. OCTOBER 11, 2000 — NLCS Game One: Mets 6 CARDINALS 2

Mike Piazza had been a regular-season beast his entire career, but postseason opponents had yet to fully feel his wrath. Then, in the course of opening the series that would determine the pennant, Mike whacked a first-inning RBI double off Darryl Kile that inspired third base coach John Stearns to shout into his Fox clip-on mic, “The Monster is out of the cage!” By invoking for national consumption his fellow hard-nosed catcher’s clubhouse nickname, Bad Dude had enhanced Piazza’s legend. More importantly, Piazza, en route to batting .412 and slugging .941, had enhanced the Mets’ chances to take command of the NLCS. (Mike Hampton’s seven shutout innings didn’t hurt, either.)

55. OCTOBER 4, 1988 — NLCS Game One: Mets 3 DODGERS 2 55. OCTOBER 4, 1988 — NLCS Game One: Mets 3 DODGERS 2

The invincible Orel Hershiser, he of the 59-inning scoreless streak that he rode to the end of the season, loomed large. But the Mets were on a roll of sorts, too. Not only had they come into the 1988 playoffs after tearing off 29 wins in 37 games, they hadn’t lost a postseason contest since a certain ball rolled through a certain Red Sox first baseman’s legs. This was a different October, but that old Met magic was brought to bear at Dodger Stadium. In the top of the ninth, with Hershiser ahead, 2-0, the Mets went to work like it was 1986. Darryl Strawberry cracked Orel’s latest string of goose eggs with a run-scoring double, and Gary Carter — the same Kid who started that tenth-inning rally versus Boston in Game Six two years before — stroked a double into center field to bring home Straw and Kevin McReynolds for a 3-2 New York edge. When Randy Myers set down L.A. in order in the bottom of the ninth, the Mets were up where they belonged: one-nothing over the Dodgers and three games from a presumed return to the World Series.

54. OCTOBER 19, 1986 — WS Game Two: Red Sox 9 METS 3

Fans of elite starting pitching couldn’t have asked for a better matchup to salivate over: the best of 1985, Dwight Gooden, versus the best of 1986, Roger Clemens. When the epitome of “highly anticipated” was over, connoisseurs of hurling were spitting the bad taste out of their mouths. Clemens, the 24-4 dynamo of the regular season, was a few shades shy or ordinary, not lasting long enough to earn a win. But there was a win for Boston, given that Red Sox batters more than made up for Clemens’s 4⅓ innings of five-hit, four-walk, three-run ball. The likes of Boggs, Barrett and Buckner jumped ugly all over Gooden, whose 24-4 slate from ’85 might as well have occurred in the prior decade. Doc’s six earned runs allowed all but buried the Mets by the fifth inning, and the throwback effectiveness of erstwhile Bosox closer Bob Stanley (3 IP, 0 R) prevented any chance of resurrection. The Mets were down oh-two in the World Series and could have been easily mistaken for dead.

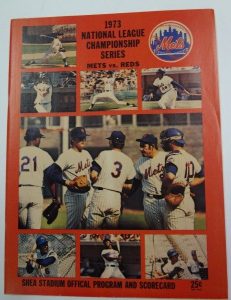

53. OCTOBER 9, 1973 — NLCS Game Four: Reds 2 METS 1(12)

The villain gets his vengeance in what turns into the penultimate chapter of a playoff potboiler, as Pete Rose’s twelfth-inning homer off Harry Parker proves the difference. Rose’s sprint around the bases, as he raised a fist in the air to Shea’s vocal displeasure, cemented his role as Flushing’s quintessential heel. Of course the game was still in progress, with the home team in line to clinch a pennant, thanks to Rusty Staub’s dramatic robbery of Dan Driessen at the right field wall in the eleventh. Ironically, the Met crowd got more Rose and less Staub from the bargain, for Rusty wrecked his right shoulder and was doomed to sit out deciding Game Five, which was going to provide its own page-turning chapter to the proceedings. Obscured in the passions of Game Four: four-and-a-third scoreless innings of relief from Tug McGraw on top of six-and-two-thirds frames from George Stone that were marred by only a Tony Perez solo blast. Alas, the Mets could do next to nothing (1 R, 3 H) versus Red hurlers Fred Norman, Don Gullett, Clay Carroll and Pedro Borbon.

52. OCTOBER 9, 2015 — NLDS Game One: Mets 3 DODGERS 1

When the Mets were scuffling at midseason, they rated only one National League All-Star, Jacob deGrom. When the Mets roared to a division title, there were many who performed in stellar fashion, but there was no overlooking the guy who’d been great for them all along. Starting the Mets’ first postseason game in nine years, the NL’s most recent Rookie of the Year lived up to all his burgeoning billing, going seven strong innings, striking out thirteen Dodgers, and outdueling defending Cy Young/MVP Clayton Kershaw. Jake’s supporting cast, featuring Daniel Murphy (a leadoff homer in the fourth) and David Wright (a two-RBI single in the seventh), made sure the Mets ace’s best efforts weren’t for naught.

51. OCTOBER 25, 2000 — WS Game Four: Yankees 3 METS 2

With the Mets back in the Subway Series following their Game Three victory, two battles within the battle within the intracity war defined the fourth game. First — meaning upon the very first pitch in the top of the very first inning — Derek Jeter took Bobby Jones deep to give the Yankees an immediate lead. A one-run deficit shouldn’t have seemed impossible to overcome, but it would be, even when the Mets encountered their most glittering opportunity of the night. Come the bottom of the fifth inning, with the Mets trailing, 3-2, and Mike Piazza coming to the plate having already homered in the third off Denny Neagle, Joe Torre lifted his starter in favor of David Cone. This wasn’t the 20-3 Cone from 1988 who rescued the Mets from the brink in Game Six of that year’s NLCS, nor was it the Cone who was so indispensable to three Bronx world championships over the previous four Octobers. This was David Cone with a regular-season ERA pushing seven, removed from the rotation, and all but shunted to the shadows for the balance of this postseason. Yet Torre called on his 37-year-old veteran for one mano-a-mano at-bat. As Jeter was versus Jones, Cone proved to be, shall we say, the mano against Piazza, gaining the upper hand as he induced an inning-ending popout. Four innings remained, but, per on-field pregame entertainers the Baha Men, the Mets’ chances to do anything constructive had, like the dogs, been let out.

50. OCTOBER 16, 1973 — WS Game Three: A’s 3 METS 2 (11) 50. OCTOBER 16, 1973 — WS Game Three: A’s 3 METS 2 (11)

49. OCTOBER 6, 1973 — NLCS Game One: REDS 2 Mets 1

Twenty-seven times between his 1967 debut and the end of the 1973 regular season, Tom Seaver had gone at least eight innings, given up no more than two runs, and won nothing. The postseason isn’t the ideal setting for manufacturing microcosms, but in October of ’73, a larger baseball audience got a taste of what Mets fans had seen beset Seaver repeatedly during the first stages of his Hall of Fame tenure. Tom at his most Terrific; the Mets not scoring; the Franchise not winning; and the franchise losing. As part of the coda to his stressful second Cy Young season, Seaver unfurled two superhuman efforts versus two of the signature squads of the Seventies: 8⅓ IP, 2 ER, 6 H, 0 BB, 13 SO at Cincinnati; 8 IP, 2 ER, 7 H, 1 BB, 12 SO against Oakland. For his troubles, Tom came away with a loss and a no-decision, with the Mets losing the latter in extra innings at frigid Shea.

In the NLCS at Riverfront, Tom threw a wrench into the Big Red Machine for seven shutout innings (and doubled in the Mets’ lone run in the second) before Pete Rose nailed him for the tying homer in the eighth and Johnny Bench beat him the same way in the ninth. In the World Series, meanwhile, after Seaver had won the pennant-clincher over the Reds, the Mets’ ace held the Swingin’ A’s at bay as long as he could, carrying a precarious 2-0 lead to the sixth and a 2-1 lead to the eighth. This time, there were no opposition longballs, though the opponents’ most famous power hitter would offer words of praise after first-hand exposure. “Blind people,” Reggie Jackson marveled, “come to the park just to listen to him pitch.” What people watching and listening saw and heard after Seaver left Game Three was the A’s weave a go-ahead run in the eleventh inning on a walk, a missed strike three and a single. According to Baseball-Reference, only five postseason pitchers approximated Seaver’s lines from these two games versus the Reds and A’s in 1973 during the rest of Seaver’s lifetime, and none of them did it more than once.

48. OCTOBER 22, 1986 — WS Game Four: Mets 6 RED SOX 2

47. OCTOBER 21, 1986 — WS Game Three: Mets 7 RED SOX 1

Tourists who visit Boston are often drawn to the Freedom Trail, a walkable exploration of sixteen historic sites designed to tell a story of America’s founding. That wasn’t the trail the Mets were seeking out on their trip north in the middle of the 1986 World Series. Trailing two games to none, they were concerned only with the comeback trail. They found it immediately, starting with Lenny Dykstra leading off Game Three with a homer around Fenway Park’s right field foul pole, continuing through the Red Sox’ blown rundown play later in the first inning, and culminating in a pair of victories that re-established the 1986 Mets as the threat they had been dating back to Opening Day. Two starting pitchers who came embroidered with a Red Sox storyline — Bobby Ojeda who used to pitch for them and Ron Darling who grew up rooting for them — shut down Boston’s bats, while Gary Carter belted two home runs and totaled six RBIs. New England entered the middle portion of the Series blanketing itself in sweep dreams. New York’s invasion surely changed the course of Red Sox events.

46. OCTOBER 16, 2000 — NLCS Game Five: METS 7 Cardinals 0

Mike Hampton unwittingly threaded a needle of accomplishment and perception, giving Mets fans something they’d very badly wanted for a long time yet garnering very little in the way of lasting gratitude. Hampton had been imported from Houston to push the Mets past the heartbreak of having their postseason end in the NLCS as it did in 1999. The lefty had won 22 games for the Astros. He seemed a good bet to make the difference another lefty, Kenny Rogers, couldn’t. In the fifth game of the 2000 NLCS, Hampton delivered, authoring a shutout that clinched the Mets’ fourth pennant. His three-hitter stamped the Mets’ ticket to their first World Series in fourteen years and, when paired with a similar splendid outing in Game One, earned him MVP honors for the League Championship round.

When Hampton had finished being his best self, the idea of participating in the 2000 Fall Classic loomed as an unalloyed positive — the ALCS was still in progress, so its outcome might have meant a trip to Seattle — and Mike was, naturally, still under contract to the Mets. Nobody knew how the World Series would unfold and nobody knew where Hampton, with free agency pending, would decide to pitch in 2001…or how inartfully he’d articulate his choice. You won’t learn any of that in any school (in Denver or anywhere else), but it doesn’t hurt to review how much Mike meant to the Mets at one very important franchise peak just in case there’s an exam.

45. OCTOBER 12, 1969 — WS Game Two: Mets 2 ORIOLES 1 45. OCTOBER 12, 1969 — WS Game Two: Mets 2 ORIOLES 1

Wasn’t it enough that the Miracle Mets had reached the World Series? No man among their ranks would have said yes, and after losing their first game in Baltimore, they set out to guarantee they’d snare more than a runners-up trophy for 1969. Jerry Koosman was so determined to put the Mets on the board that he kept the Orioles completely off it, no-hitting the home team until the seventh. Donn Clendenon had given Kooz a one-run lead in the fourth with a leadoff homer and it stood tall until three innings later when Brooks Robinson singled home Paul Blair from second. The less-celebrated of starting third basemen, Ed Charles, instigated a two-out, ninth-inning rally. The Glider registered a base hit, raced to third on a Jerry Grote single, and crossed the plate when Al Weis singled to left. In the bottom of the ninth, with two out and Ron Taylor on, it was Ed topping Brooks one more time, as Charles grabbed Robinson’s grounder and threw it to Clendenon to close out the Mets’ first-ever World Series win.

44. OCTOBER 5, 1999 — NLDS Game One: Mets 8 DIAMONDBACKS 4

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Unit? Anybody with any sense while Randy Johnson was in his lengthy prime, but the ’99 Mets didn’t have time to fully consider their mound opponent’s perennial Cy Young credentials as they arrived in the postseason essentially after the last minute. Having completed their 162-game season knotted with the Reds for the NL’s final playoff spot, they had to contest and capture a tiebreaker in Cincinnati to qualify for the Wild Card. Well, they did that, as Al Leiter blanked the Reds, 5-0. A quick champagne shower and long westward flight later, they were in Phoenix to take on the Western Division champions. The most venomous Snake in Arizona, who had struck out 364 batters in 1999, awaited them. The Mets didn’t wait to get to whacking. Two-hole batter Edgardo Alfonzo homered to give the Mets a quick lead in the first. John Olerud, in an episode of lefty-on-lefty crime to which the Unit was rarely victimized, bopped a two-run dinger in the third to increase the Mets’ edge to 3-0. The Mets led until the sixth, when their starter, Masato Yoshii, ran out of gas. Having survived the initial New York onslaught and granted a cleanish slate via a 4-4 tie, Johnson got characteristically tough. Through eight, the Big Unit had racked up eleven strikeouts. Randy’s late-game magic finally evaporated as the Mets loaded the bases in the top of the ninth. The Unit exited. Bobby Chouinard entered. With two outs, Fonzie returned, detonating a grand slam that ensured the Mets would attain the advantage in their first postseason series since 1988.

43. OCTOBER 16, 1999 — NLCS Game Four: METS 3 Braves 2

They were off the mat. They had life in them. They were naturalized citizens of Cliché Stadium. However you termed it, the Mets absolutely needed to win what could have been their last game of the twentieth century, and they did. As was the case regarding basically everything in 1999, it wasn’t easy. Rick Reed dueled John Smoltz effectively for most of seven innings, but a couple of solo home runs left Reed and the Mets behind, 2-1, in the top of the eighth. The backs/wall ratio was overwhelming, but it wasn’t over until it was over, and it most definitely wasn’t over. In the bottom of the eighth, Roger Cedeño, Melvin Mora and John Olerud (who had earlier homered) engineered a breath-holding rally that not only created the necessary two runs to constitute a comeback, but they scored the tying and go-ahead runs with John Rocker on the mound, which made the resuscitation even sweeter. Armando Benitez held Fort Ninth Inning for the save and, yup, the Mets lived another day.

42. OCTOBER 4, 2006 — NLDS Game One: METS 6 Dodgers 5

In an echo of the NBA’s old “three to make two rule,” the Mets improvised a scenario that indicated the ball was destined to bounce their way in their first postseason appearance in six years. John Maine, a surprise starter with Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez sidelined by a calf injury, allowed the first two runners of the second inning on base via singles. With Jeff Kent on second and J.D. Drew on first, the Dodger threat was palpable this late afternoon in Flushing. When Russell Martin lashed a ball to the right field corner, Kent seemed a sure bet to score. But Shawn Green handled it cleanly off the wall and made a quick relay to second baseman Jose Valentin, who in turn unleashed a dart to Paul Lo Duca. Lo Duca turned and tagged ex-Met Kent, who did not get a very good jump off second. If one out wasn’t enough to electrify the Shea crowd, what happened a beat later did the trick. Drew kept charging and ran into the Met catcher’s second tag of the play, touching off an jolt of joy as loud as anything takeoffs out of or landings into LaGuardia could produce. Martin took second amid the breathtaking pair of home plate outs and scored on Marlon Anderson’s ensuing double, but the Dodgers taking a 1-0 lead felt like a Los Angeles letdown. Though there’d be some back-and-forth on offense — Carlos Delgado doing the most to carry the Mets forth by going 4-for-5 with a homer — the 9-4-2 chain of DP events instigated by three former Dodgers defined the day in the Mets’ favor and set the series’ trajectory on its way.

41. OCTOBER 6, 1969 — NLCS Game Three: METS 7 Braves 4

Had 1969 taken place in 1968, this step would have been unnecessary, but the Mets’ place in 1968 was ninth, while in 1969, the only thing the best record in the National League won you was a spot in something called the Championship Series. The 100-62 record the Mets notched in the regular season was indeed tops in the senior circuit, but for the first time since the NL eliminated a four-team playoff format implemented to determine its 1892 champion, the best record wouldn’t necessarily add up to a league pennant. For that honor, the Mets would have to complete their business against the Atlanta Braves, the 93-69 team with the best record in the division opposite them. In this inaugural showdown between East and West, the Mets showed the Braves on whom the league’s sun rose and set. Henry Aaron may have put the visitors out front in the first (he homered in every NLCS game) and Gary Gentry may have been less than his sharpest thirteen days after throwing the shutout that clinched the division, but the Mets would not be denied. Tommie Agee, Ken Boswell and Wayne Garrett all homered. Nolan Ryan threw a mere seven innings of relief. And, in the ninth inning, with two out and the Mets up by three, when Tony Gonzalez grounded to third baseman Garrett, who threw to Ed Kranepool at first, Ralph Kiner explained the result simply and succinctly: “The Mets are National League champions!” The team that had never remotely challenged for any kind of title — other than worst ballclub ever — had now earned its second flag of 1969 and was poised to compete for its third and ultimate.

40. OCTOBER 10, 2015 — NLDS Game Two: DODGERS 5 Mets 2

For thirteen regular seasons, the name Chase Utley elicited little worse than grumbles among Mets fans who had grown used to the Phillies’ All-Star second baseman occasionally contributing to defeats of their beloveds (it wasn’t for nothing that the area by the right field foul pole at brand new Citi Field had been grudgingly dubbed Utley’s Corner). But by the second week of October 2015, the Mets were beyond the regular season and Utley was no longer a Phillie. The Dodgers had traded for the six-time All-Star second baseman, and fate would pit the former division rival against the NL East champions…and then fate would really bring it on where these two entities were concerned. Utley was on first base in the home seventh at Dodger Stadium, with Kiké Hernandez on third, as Bartolo Colon came on to relieve Noah Syndergaard and protect a 2-1 Met lead. Howie Kendrick’s chopper to second scored Hernandez and unleashed havoc. Daniel Murphy’s attempt to start a 4-6-3 double play went for naught as Utley slid into shortstop Ruben Tejada rather than the bag Tejada was straddling. Tejada suffered a broken leg. Utley incurred the wrath of Mets fans a continent away. Worse, from a New York perspective, Utley was awarded second despite never touching the base he nominally sought. The mess spiraled into a four-run rally for L.A. and hard feelings that would not dissipate soon or, really, ever.

39. OCTOBER 5, 2000 — NLDS Game Two: Mets 5 GIANTS 4 (10)

Several Mets played the roles those who intensely observed them expected to see. Al Leiter threw eight strong innings, allowing only two runs. Edgardo Alfonzo ripped a clutch ninth-inning home run to extend the Mets’ lead to three runs. And Armando Benitez…well, Armando was Armando, the closer who shut down most every ninth inning except for the ones that seemed a little more important than the rest. J.T. Snow drove a three-run homer out of Pac Bell Park to tie the contest and send it to extras. But then a couple of additional characters got their hands on the script. With two outs in the top of the tenth, Darryl Hamilton doubled and Jay Payton followed immediately with a run-scoring single to regain the lead for New York. Finally, it came down to two new names deeply known by anybody who’d been watching the Mets vie for victory over the past decade-plus. In the batter’s box, with a runner on first and two out, was Barry Bonds, about as dangerous a lefty hitter as baseball history had to offer. On the mound, John Franco, the veteran southpaw whose career was dedicated to putting the clamps on the most lethal of lefthanded batters. Franco vs. Bonds worked its way to a full count. Finally, on a fairly borderline pitch, Bonds was called out looking. Strikeout and win to Franco, split in San Francisco for the Mets before both teams would split for the airport and a trip to Shea.

38. OCTOBER 27, 2015 — WS Game One: ROYALS 5 Mets 4 (14)

37. OCTOBER 21, 2000 — WS Game One: YANKEES 4 Mets 3 (12)

For a franchise that made a habit of waiting forever to get back to the Fall Classic, the Mets sure had a knack for sticking around on the nights they arrived. The opener of the 2000 World Series, an event for which they hadn’t qualified since 1986, was an antsy affair in the Bronx. Despite several opportunities unredeemed (most notably one wasted on Timo Perez not hustling his head off from first to home on a Todd Zeile double that just missed going out), the Mets nursed a 3-2 lead to the bottom of the ninth. Alas, Armando Benitez lost a ten-pitch battle to Paul O’Neill and, after walking the Yankee right fielder, eventually let him score. The Mets hung around Game One until the twelfth, when, with two outs and the bases loaded, their former shortstop, Jose Vizcaino, singled in Tino Martinez to put the Mets in a one-game hole. If it wasn’t exactly déjà vu all over again fifteen years later, the next time the Mets started a World Series generated an eerily similar storyline. This time it was a 4-3 lead at Kansas City gone awry when Alex Gordon lined a Jeurys Familia quick pitch over the Kaufman Stadium wall to tie things up. Tied they stayed into the fourteenth, until Eric Hosmer put everybody to bed via a bases-loaded sac fly. Two very long nights (ten hours total), two deceptively deep one-nothing deficits.

36. OCTOBER 21, 2015 — NLCS Game Four: Mets 8 CUBS 3

The Cubs had a billy goat. They had a cinematic omen. They had ivy, romance, perhaps the heart of America on their side. But the Mets had Lucas Duda, and Duda didn’t care that in the 1989 feature film Back to the Future II, this date in Mets history was the date the Chicago Cubs finally won a Fall Classic. The Mets’ slugger wasn’t in a movie, though he certainly earned a starring role in highlight reels by bashing the first-inning grand slam that sent the North Side’s world championshipless streak at least another year into the future. The Mets took that 4-0 lead and embellished it ASAP when Travis d’Arnaud added a solo home run. The Mets never trailed in the game, just as they never trailed in the series. When Jeurys Familia struck out Dexter Fowler in the ninth — after NLCS MVP Daniel Murphy had homered for a record sixth consecutive postseason game (and the ghost of the goat of a 1945 legend named Murphy failed to haunt Wrigley with any kind of good home team luck) — it was the Mets who had accomplished the stuff of modern myth: a four-game sweep and their fifth National League pennant.

35. OCTOBER 31, 2015 — WS Game Four: Royals 5 METS 3 35. OCTOBER 31, 2015 — WS Game Four: Royals 5 METS 3

The Mets had been flipping Daniel Murphy’s coin throughout the 2015 postseason, and it had come up heads more often than not. One too many flips, however, left the ballclub on its tail. With seven home runs in the NLDS and NLCS behind him, it was easy to forget that Murph’s defense at second base had never been his strong suit. Yet in the eighth inning of the fourth game of the World Series, all of Metsopotamia was reminded that the extraordinary autumnal offensive performer had generally always lacked a position. He had made himself a suitable second baseman, but then a ground ball confounded him. The Mets were clinging to a 3-2 lead, as Tyler Clippard walked Ben Zobrist, then Lorenzo Cain with one out. Jeurys Familia took over and got the desired result from Eric Hosmer. It was a grounder to second. Except it was mishandled by the Mets’ second baseman, and Zobrist scored the tying run. Two singles to right followed and the Royals a built a two-run lead. Daniel attempted to make amends for his error with a one-out single in the bottom of the ninth, but Yoenis Cespedes (speaking of 2015 heroes running out of steam) would get caught off first on Lucas Duda’s game-ending line drive to third and the Mets landed a game away from elimination.

34. OCTOBER 21, 1973 — WS Game Seven: A’S 5 Mets 2

The name “Oakland” doesn’t translate in some ancient tongue to “land beyond belief,” but that’s where the Mets wound up. The team that rode stifling starting pitching and the You Gotta Believe mantra from last place most of the summer to the precipice of a second world championship came up one game short in the Oakland Coliseum. Jon Matlack, who had been so good in Games One and Four, not to mention Game Two of the NLCS, didn’t have his best stuff. The lefty didn’t last three innings, having been taken deep for a pair of two-run homers by Bert Campaneris and soon-to-be-named MVP Reggie Jackson. Ken Holtzman and Rollie Fingers teamed to tame the Mets into the ninth inning, but apropos of the way the 1973 Mets kept pushing from the rear, New York brought one run in and put two runners on in the ninth, provoking Dick Williams to call on Darold Knowles to extinguish their final fire. Knowles became the first pitcher to appear in all seven games of a World Series. With everything on the line, he could have faced potential pinch-hitter Willie Mays, the legend on the edge of retirement, but Yogi Berra stuck with regularly scheduled batter Wayne Garrett. Garrett popped up and the A’s finally deflated the Met balloon that stayed aloft longer than anybody would have guessed when they themselves were stuck in the basement as late as August 30.

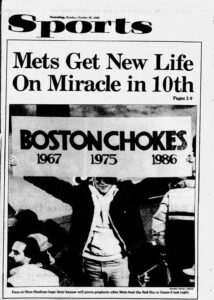

33. OCTOBER 12, 1988 — NLCS Game Seven: DODGERS 6 Mets 0