The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 6 March 2026 1:16 pm It’s the time of the year meant for looking ahead. To Carson Benge not being Don Bosch. To Vidal Bruján and Mike Tauchman potentially making themselves more useful than Bill Pecota. To Nolan McLean overcoming vertigo-like symptoms so he can pitch in the WBC, then not getting hurt in the WBC (which goes for all Mets in the WBC). To the holdover veteran pitchers turning around their second-half miseries from last summer. To the winter imports tasked with manning corner infield positions learning where to stand and when to bend. Some of the advice Bo Bichette told SNY’s Michelle Margaux that he received from accomplished third basemen like Matt Chapman and Nolan Arenado included, “Make it your own. Get low. Don’t make it too complicated. Just be an athlete.”

For us, the perennial advice isn’t too complicated, either. Just be a fan, especially come March. It’s the time of the year when we prefer to get high. On baseball. On hope. On history, despite the need to look forward, because why would we be here, looking ahead, if we weren’t so informed by what’s piled up behind us?

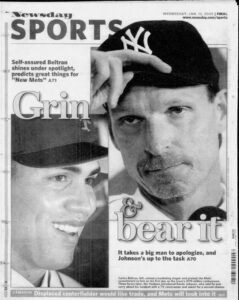

Piling up in Flushing last year, according to Newsday’s perusal of a “recent final disclosure filed by the club,” was more than $300 million in ballpark revenue. I didn’t think I’d bought that many pretzels, but they were on discount most every Tuesday. I wasn’t alone in getting my five bucks’ worth. Record Citi Field attendance filled the ballpark to be let down by the baseball in 2025, if happily distracted by the chance to get away from life. More than $150 million in ticket sales. More than $50 million in ad revenue. Close to $40 million worth of concessions. Plus a whole lot in suites and such, along with plenty for parking. I wouldn’t know about the last one since I take the train. I also wouldn’t know if the reported total of $311.4 million is a lot relative to what it normally is, but Newsday says it really is — 19.4% greater than what the Mets took in during 2024. The 2025 bottom line reaped the rewards of the excitement generated in 2024. Any circumspection that infiltrates our aspirations to be high on baseball hope in 2026 may be a byproduct of not being thrilled by how 2025 came apart. One way or another, history is always driving us.

The Mets issued a statement to Newsday that “the organization remains focused first and foremost on delivering he best fan experience in baseball, continually looking for ways, from food and beverage to retail, in-game entertainment and beyond to ensure a top-tier experience at Citi Field.” It doesn’t mention better play on the field, but we’ll take that as a baked-in goal of every year. We’ll also acknowledge that the entire package, whether it’s improving on an 83-win campaign or continuing the largesse of $5 Tuesdays, ensuring that once a week pretzels and a few other staples will remain only marginally rather than comically overpriced, represents a better state of affairs to what Jack Lang reported in the Daily News 47 years ago this month:

“The prospects of the Mets having a financially successful season in 1979 are remote. Because they do not have a team to sell, Mets’ ticket sales are down. Even radio-TV sponsors are tough to come by. Already the number of TV games has been cut by about 20 games this year and there is a chance some games will not heard over the radio. All of this adds up to another financially disastrous season…one which could result in the Payson family selling the club by October, the end of the corporation’s fiscal year.”

Which, besides Lee Mazzilli’s quest to keep his average above .300, became our primary rooting interest as that year unfolded.

One of the losses that touched a historical nerve during this past Mets’ offseason was the passing in October of Lorinda de Roulet, who ran the organization for one season, perhaps its roughest season ever, 1979. As anybody who constituted any fraction of the 788,905 fans who passed through Shea Stadium’s turnstiles as a paying customer in 1979 will attest, the happiest day of the de Roulet stewardship — itself the end result of the lack of an effective succession plan following the death of her mother Joan Payson in 1975 — was when it ended. Linda, as those who knew he called her during her 95 years on the planet, may have truly wanted the best for the Mets when she succeeded the reviled M. Donald Grant as board chairman, but the resources simply weren’t there. Linda’s father Charles was not a baseball fan the way Joan was (and was said to pull for the Red Sox when he rooted at all), but he did control a vast majority of Mets stock. Lang informed us in the News during the Spring his daughter took charge that Charles had “already tightened the purse strings by refusing to pour any more of family money into a losing operation. […] At the age of 80, he sees no future in it.”

Thus, when the club was sold to the group headed by Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon in January 1980 (much as was the case when the club was sold by the Wilpons to Steve Cohen in November 2020), a world of conceivable possibilities opened up. After three straight seasons of last-place finishes witnessed in person by ever fewer Metsochists, there was finally a future to all this, soon, if not immediately. Whereas the de Roulet ownership couldn’t spend, the new regime loomed as a legitimate contender to sign free agents in the years ahead. The years ahead represented a reasonable timeline, as new chief operating officer Wilpon promised to spend “whatever is necessary to see a World Series flag flying over Shea Stadium in the ’80s.” The year ahead singular would be a tougher task to make better, as most of the plum free agent names were already off the market by the time the sale of the team went through. Then again, two-time National League MVP Joe Morgan, one of the all-time great second basemen, coming off his eighth consecutive All-Star selection, remained available.

While the Mets were now able to go after a player of Morgan’s stature, it didn’t mean they would take a late-career flyer on the surefire Hall of Famer. Manager Joe Torre told Bill Madden in the Daily News, “The future of this ballclub is Taveras and Flynn. I know Joe Morgan can hit, but unless he could play third base or somewhere else for us, I don’t know if he could help us.”

A statement of such a definitive nature regarding the Metsian future indicates it might not have been de Roulet’s leadership that was the problem with those Mets, but in the context of the moment, Torre’s take wasn’t as ludicrous as the intervening decades make it sound. Second baseman Doug Flynn was a terrific fielder who somehow drove in 61 runs while batting eighth every day for a cellar-dweller in 1979, while shortstop Frank Taveras came over from the Pirates in April and proceeded to shatter the Mets’ single-season stolen base mark, swiping 42 bags. From the perspective of building a ballclub during that era, you could view your middle infield as a foundational block, add the ability to spend to shore up other positions, and, presto chango, the future of the Mets fan imagination, à la Taveras runs wild!

The actual future? It saw Frank Cashen hired as general manager in February of 1980, and, once the 1981 season ended, Cashen ridding himself of Torre, Flynn, and Taveras before the throngs in Times Square could count down to 1982. “You’ve heard about incentive clauses for ballplayers, but here’s a new twist,” Jack Lang wrote in The Sporting News during Christmas week. “Cashen offered a pair of Gucci loafers to whichever one of his aides managed to complete a deal for Frank Taveras. The winner has not been announced, but Taveras is gone.”

Perspectives in baseball change, just like calendars change, and it can happen quicker than you’d suspect. For example, it’s suddenly March, not just for baseball, but for everything. How did it get to be March? In baseball terms, how is every player who needs to be somewhere not yet somewhere? With not quite three weeks to go before Opening Day, it’s getting late early within the leagues of grapefruits and cacti, though one supposes it’s not too late until it is. A mere two years ago, J.D. Martinez waited until there was about a week to go to come to terms with the New York Mets. He wasn’t available to play until late April, but there was time enough to do a deal and make an impact.

Still, better to get on a team before teams make other plans. Many are, even if took them well into February to get somewhere. Like free agent Starling Marte, who has signed on with the Royals. Maybe we won’t miss Starling in the sense that he’s going to be as productive for Kansas City as he was for us circa 2022, but he was an endearing Met for four seasons, and you always miss that. Like Old Friend™ Michael Conforto, who has signed on with the Cubs. We’ve had a bunch of years to stop missing Michael, and I’ve rarely thought how much better off the post-2021 Mets lineup would be with his bat within it, but I see his name and I think of a hot Met prospect who came up to herald a pennant drive in 2015 and caught fire to spark a playoff push (albeit one that fell short) in 2019. I watch him occasionally go deep on a Mets Classic and wonder how he never quite became what we projected he would. Good for Michael catching on somewhere, even, as with Starling in K.C., if it’s with a team we’re historically predisposed to not like. Since we need old enemies to balance out our Old Friends, it’s perversely reassuring to know Rhys Hoskins found a deal in Cleveland. He’s not Chase Utley in the bottom of the barrel of our esteem, but he’s the closest thing I can think of in terms of active major leaguers I could fall out of bed in the dead of winter and instinctively start booing, mostly from that episode of him feigning boo-hooing at Citi Field two years ago.

Juan Lagares announced his retirement in February. I saw Juan Lagares play in last season’s Mets Alumni Classic, a pretty good indicator that he was not otherwise occupied by the rigors of a baseball playing schedule from late March to late September. Relatively few players seem to come right out and say “I’m done playing” the moment they’ve registered their final statistic on Baseball-Reference’s overview page. Only the elite inspire retirement tours. Only the supremely self-assured know immediately when one part of their life is ready to give way to another. Everybody else presumably needs time to weigh opportunities or the lack thereof. For example, the aforementioned J.D. Martinez hasn’t swung a bat for the record since Game Four of the 2024 NLCS, a postseason when he shared designated hitter duties with the currently unsigned Jesse Winker. Said he planned to play in 2025 last Spring, but apparently had no takers. Competed in something called a Celebrity Pickleball Showdown in the fall (implying he can still hit some). He’s played no baseball that we know of, but J.D., 38, isn’t retired from the game until he says he is, whether or not the game has decided it has moved on from him.

J.D. the DH never did anything with a glove when he was a Met. Conversely, Juan did wonders with one from 2013 into 2020. He then took his equipment to the L.A. Angels for a couple of years, the last of them in 2022. Every winter since then, the keeper of the glove where extra-base hits went to die plied his craft for the Aguilas Cibaeñas in the Dominican. Our most recent Gold Glove winner (2014, back when run prevention was simply called defense) decided to wait until his 37th birthday approached to make it official that he was done for all seasons.

Winter ball, we on the mainland might want to remind ourselves, is some kind of ball. I’ve been reading How Life Imitates the World Series by Tom Boswell, the Washington Post’s legendary baseball columnist (back when the Post covered sports), and one of the stops Boz makes along his long-ago journey is Puerto Rico’s winter league, where the author finds Ruben Gomez winding down his pitching career. If you’re like me, you might recognize Gomez from the New York Giants of the 1950s, a key component of the rotation that shut down the Indians in the 1954 World Series. What I didn’t know anything about was the length of Ruben’s career between major league calendars. Per his SABR bio, Gomez pitched in the Puerto Rican Winter League for 29 seasons. By the late 1970s, when he wasn’t engaged in his passion of building cars “from the frame up, selling some, renting others, but always keeping the fastest for himself,” he was, in the neighborhood of 50 years old, pitching for Vaqueros de Bayamon, or the Bayamon Cowboys. The experienced righty didn’t concern himself too much with numbers, evidenced by his predilection for disregarding speed limits.

“Toward sundown,” Boswell wrote in his 1982 collection, “he heads for the ballpark, negotiating the deserted beachside highway at 120 miles per hour. […] If the police stop him, Gomez simply blurts, ‘I am hurrying to my wife.’ Only once did a policia dare to tell the island’s venerable celebrity, ‘Señor Gomez, all of Puerto Rico knows that your wife died seven years ago.’

“‘In that case,’ said Gomez, switching to his changeup, ‘I’m going to the cemetery.’”

Still revealing a pulse of sorts seventeen years since it was torn down is the very same facility few were paying to enter amid the reign of Linda de Roulet. Once the American League champion Toronto Blue Jays and 41-year-old Max Scherzer agreed to continue their professional relationship, it guaranteed (good health willing) that the 2026 Major League Baseball season will include a player who played at Shea Stadium. Without dismissing any of his 42 regular-season starts as a Met, including the one that clinched us a playoff spot in 2022, this may turn out to be Scherzer’s defining Met legacy. Three others who earned Shea stripes pitched during 2025, but each of them — Clayton Kershaw, David Robertson, and Rich Hill — has confirmed some version of retirement from baseball. Kershaw is with Team USA in the World Baseball Classic, but is otherwise inactive. Scherzer, like Kershaw, first came up in Shea’s last year, 2008. He got into a game there that June when he was a Diamondback (a helluva game it was). Max went a long way from there. Shea didn’t, but now it gets to maintain a glimmer of existence, as Scherzer nails down his status as this generation’s Pete Rose. In 1986, Rose became the last active player who could say he played at the Polo Grounds, outlasting Rusty Staub, whose last game was in 1985, and Joe Morgan, whose baseball-playing future reached its limit in 1984 (two years beyond Taveras’s, if a year shy of Flynn’s).

Even as the WBC supplants MLB on Spring’s center stage for a spell, a couple of other acronyms deserve a moment in the March sun. One is HBP, which should never happen to anybody, unless it’s the gentlest of sleeve-brushing hit-by-pitches taken for the team with the bases loaded. HBPs can be sore subjects in more ways than one. Yes, Ruben Gomez was an icon of winter ball longevity, and he surely went seven-and-a-third in defeating Cleveland in Game Three of the ’54 Fall Classic, but if his name rings a resonant bell at all, it’s likely from his encounter with Joe Adcock of the Milwaukee Braves in 1956. An Associated Press account detailed the incident:

“A howling crowd of 33,239 saw one of baseball’s wildest scenes last night as the Giants’ Ruben Gomez hit Joe Adcock twice with a ball — once as Adcock charged the mound — and then bolted like a gunshy rabbit for his dugout, the fiery angry Braves’ slugger in hot pursuit.”

An inside pitch had nicked Adcock’s right wrist. Words were exchanged as the batter headed to first before Adcock redirected his route toward the mound. “Gomez, who by this time had a new ball,” the AP reported, “flung it at the onrushing Adcock about 25 feet way, and hit Joe on the left thigh. The 175-pound pitcher then turned tail and raced for all he was worth — his back hunched over as if he expected the worst — for the Giant dugout. The 210-pound Adcock was right behind.” Umpires and police officers got involved. Both players were “escorted from the game”. Joe had endured his share of injuries from being hit, which might explain some of the action and reaction. It may not have been a good look for Ruben to evade the batter, but survival skills clearly served the righty well. Remember, this is a man who was still pitching somewhere more than twenty years later.

“What would you have done with that big coming at you?” reasoned Giants manager Bill Rigney. “Probably run, too.”

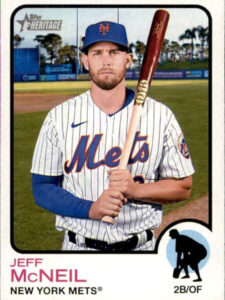

A Mets fan who has witnessed one too many HBPs in recent years might have emotionally sided with Adcock. We’ve been on the wrong end of a lot of hit-by-pitches going back a while. We lost Marte for the balance of September on a hit-by-pitch as we fought to hold on to the 2022 division title that slipped away. Starling wasn’t the only one to collect bruises in recent Met lineups. From 2018 through 2025, there’s been at least one Met to finish in the Top Ten of the National League’s hit-by-pitch leaders. For that matter, the three longest-tenured position players the Mets traded or let leave as the Hot Stove burned — Pete Alonso, Brandon Nimmo, and Jeff McNeil — are Nos. 1, 2, and 3 on the franchise’s all-time HBP leaderboard. Francisco Lindor suddenly takes over as the active team leader, with 55, many bruises from Pete’s 100, Brandon’s 87, and Jeff’s 85.

I’d say that’s not a record meant to be broken, but if that was true, Ron Hunt, whose 41 HBPs were the Met standard from the 1960s until the 2010s (and remains lodged within the Top Ten), would still have it.

One acronymic distinction that appears bound to change hands in 2026, particularly as March marches on, is that of LAMSA. Unlike HBP, you won’t find LAMSA listed on BB-Ref. LAMSA is a FAFIF exclusive, denoting Longest Ago Met Still Active. We’ve been tracking LAMSA matters so long that when Faith and Fear in Flushing began thinking about it, we were just realizing the LAMSA crown sat on the head of a very much active Jeff Kent, the same Jeff Kent who will be going into the Hall of Fame this summer alongside Carlos Beltran, who will be going into the Hall of Fame this summer with a Mets cap if no trace of a LAMSA crown on his head.

Beltran, a Met for the first time in 2005, played for ages, until 2017. But that never won him LAMSA status, nor its companion honor, Last Met Standing. Whereas LAMSA tells us what onetime New York Met has lasted the longest in the majors from his Metropolitan start date forward at any given moment, Last Met Standing speaks to a player being the last of his chronological breed to still be playing. The last 1962 Met? Ed Kranepool. The last 1963 Met? Ed Kranepool. The last 1964 Met? Ed Kranepool. It’s easy enough to monitor, even when the answer stops being Ed Kranepool. (Ed’s 1965 Mets teammate Tug McGraw outlasted him in the majors by five years.)

We haven’t had to open the LAMSA or Last Met Standing books since Spring Training in 2023, which was when one title was shifted and another was confirmed. Joe Smith, the last of the Shea Mets, from 2008, pitched his last. So did Darren O’Day. O’Day came to the Mets in 2009 and went almost as quickly, but no Met from the first Citi season outlasted him on the MLB scene, and boy did he stick around elsewhere. Once Smith’s and O’Days respective careers lacked any trace of adhesion, that left Justin Turner, a Met from 2010 to 2013, as the Longest Ago Met Still Active overall, and the Last Met Standing from 2010, 2011, and 2012.

Justin Turner, through 2025, had been around forever. From a utilityman for us to his star years with the Dodgers, spanning 2014 through 2022, to his veteran pickup incarnation. The Red Sox signed him. The Blue Jays traded for him. The Mariners signed him. The Cubs signed him. That kept him going in 2023, 2024, and 2025. It’s 2026. It’s March. He’s 41. Justin Turner is unsigned.

Meaning? Well, from a LAMSA standpoint, the Longest Ago Met Still Active when the 2026 season begins projects to be Phillie ace Zack Wheeler, though with something of an asterisk, as Wheeler — Met debut June 18, 2013 — is sitting on the injured list until at least a couple of weeks past Opening Day. That counts as active if not totally active, but it’s enough to satisfy LAMSA’s parameters…though, if we’re being picky, the next longest-ago Met who is slated to being the season on a major league roster is Angels catcher Travis d’Arnaud, the quintessential Old Friend™ whose Met debut came on August 17, 2013, two months after Zack’s and eleven days after that of Wilmer Flores, who is in the same boat as Justin Turner, Jesse Winker and anybody else stranded aboard the S.S. Currently Unsigned. The upside of free agency is you can sign anywhere you like. The downside is you have to like the deal you’re being offered, assuming you’re being offered one. Flores has received feelers of the minor league variety. He’s been a major leaguer since his 22nd birthday, August 6, 2013, and would prefer a guarantee of something at that level. The erstwhile Giant recently declared to the San Francisco Chronicle, “I’m not done playing. I’m just waiting.”

And we’re just waiting to find out who the Last Met Standing from 2013 will be. Could be Wheeler. Could be d’Arnaud. Could still be Flores, because who are we to not believe Wilmer? They were all Mets in 2014 as well, as were active major leaguers Rafael Montero and Jacob deGrom. Wheeler was on what then known as the DL in 2015, but all among Flores, d’Arnaud, Montero, deGrom, Steven Matz, and hot prospect Michael Conforto played as Mets then, that NL championship season which now sits more than a decade in the past. Weren’t they all pretty young together not so long ago?

Like Carly Simon right around the same time the Mets last won a world championship, we know nothing stays the same. But we’re willing to play the game. Baseball is coming around again. Comfort from the familiar. Anticipation for what’s unknown. Carly mentioned anticipation, too, along the way, and she used to get rides to Ebbets Field from her Stamford neighbor Jackie Robinson. That must have been something to look forward to, huh?

LONGEST AGO MET STILL ACTIVE: Chronology

• Felix Mantilla, debuted as a Met, 4/11/1962; last game in the major leagues, 10/2/1966

• Al Jackson, 4/14/1962; 9/26/1969

• Chris Cannizzaro, 4/14/1962*; 9/28/1974

• Ed Kranepool, 9/22/1962; 9/30/1979

• Tug McGraw, 4/18/1965; 9/25/1984

• Nolan Ryan, 9/11/1966; 9/22/1993

• Jesse Orosco, 4/5/1979; 9/27/2003

• John Franco, 4/11/1990; 7/1/2005

• Jeff Kent, 8/28/1992; 9/27/2008

• Jason Isringhausen**, 7/17/1995; 9/19/2012

• Octavio Dotel, 6/26/1999; 4/19/2013

• Bruce Chen, 8/1/2001; 5/15/2015

• Jose Reyes, 6/10/2003; 9/30/2018

• Oliver Perez***, 8/26/2006; 4/24/2022

• Joe Smith*** 4/1/2007; 8/2/2022

• Justin Turner 7/16/2010; 10/6/2025 (41 and currently unsigned)

• Zack Wheeler 6/18/2013; still active (will start 2026 on IL)

*Cannizzaro was Jackson’s catcher on April 14, 1962, at the Polo Grounds, so for LAMSA purposes, he debuted as a Met after his pitcher.

**During Isringhausen’s extensive injury rehabilitation period between 6/13/2009 and 4/11/2011, Paul Byrd (debuted as a Met on 7/28/1995); Jay Payton (9/1/1998); and Melvin Mora (5/30/1999) could each temporarily lay claim to LAMSA status, but Izzy ultimately outlasted them all.

*** Perez appeared to have finished his MLB career on 4/22/2021, leaving Joe Smith — whose Met debut was 4/1/2007 — as the LAMSA for the rest of the 2021 season. Perez returned to the majors on 4/7/2022, resuming his LAMSA reign, ultimately rendering Smith’s initial LAMSA status as interim.

LAST MET STANDING: 1962-2012

1962-1964: Ed Kranepool (final MLB game: 9/30/1979)

1965: Tug McGraw (9/25/1984)

1966: Nolan Ryan (9/22/1993)

1967: Tom Seaver (9/19/1986)

1968-1971: Nolan Ryan (9/22/1993)

1972-1974: Tom Seaver (9/19/1986)

1975: Dave Kingman (10/5/1986)

1976-1977: Lee Mazzilli (10/7/1989)

1978: Alex Treviño (9/30/1990)

1979: Jesse Orosco (9/27/2003)

1980: Hubie Brooks (7/2/1994)

1981-1987: Jesse Orosco (9/27/2003)

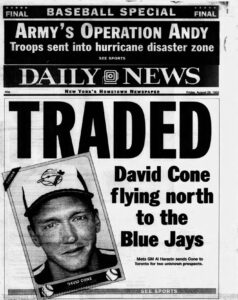

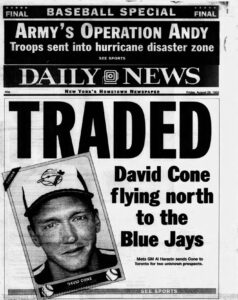

1988-1989: David Cone (5/28/2003)

1990-1991: John Franco (7/1/2005)

1992-1994: Jeff Kent (9/27/2008)

1995-1997: Jason Isringhausen (9/19/2012)

1998: Jay Payton (10/3/2010)

1999: Octavio Dotel (4/19/2013)

2000: Melvin Mora (6/29/2011)

2001-2002: Bruce Chen (5/15/2015)

2003-2005: Jose Reyes (9/30/2018)

2006: Oliver Perez (4/24/2022)

2007-2008: Joe Smith (8/2/2022)

2009: Darren O’Day (7/11/2022)

2010-2012: Justin Turner (10/6/2025; 41 and currently unsigned)

As of Spring Training 2026, two 2013 Mets — Zack Wheeler and Travis d’Arnaud — remain active, while a third, Wilmer Flores, seeks his next contract)

by Greg Prince on 24 February 2026 12:43 pm “Say, the new baseball season is coming.”

“Yeah, I guess it is. I’m not quite the diehard I used to be, but I’d like to catch up with what’s going with my favorite baseball team, the New York Mets.”

“In that case, I think it’s important that we establish some fundamentals about the Mets.”

“Fundamentals? Like what?”

“For example, every ballplayer on a ballclub has a very specific job, something the ballclub understands the ballplayer is best suited for.”

“Every ballplayer?”

“Every ballplayer. Even on the Mets.”

“Even on the Mets?”

“That’s right, even on the Mets.”

“So if I ask you about a ballplayer on the Mets, you can tell me who he is and what he does?”

A modest explainer, already in progress. “That’s correct. Go ahead and try me.”

“Who’s on first?”

“Polanco.”

“So Polanco’s a first baseman?”

“Not yet.”

“Who’s on third?”

“Bichette.”

“So Bichette’s a third baseman?”

“Not yet.”

“Who’s in left?”

“Soto.”

“So Soto’s a left fielder?”

“He has been. More recently he was in right.”

“I see, I think. Well, who’s in right?”

“I dunno.”

“I dunno is a peculiar name for a ballplayer, even on the Mets.”

“No, I’m telling you I dunno yet who’s gonna be the Mets’ right fielder.”

“Then how can you be so sure about the other positions I asked about?”

“Because they told me.”

“Who told you?”

“The Mets.”

“The Mets told you Polanco’s gonna be on first even though he’s not a first baseman, Bichette’s gonna be on third even though he’s not a third baseman, and Soto’s gonna be in left even though he’s not a left fielder.”

“But he has been.”

“Not lately, though?”

“No, Soto was a right fielder.”

“Soto was a right fielder?”

“Practically every day last year.”

“Soto was in right?”

“Right.”

“Wasn’t he on third?”

“That was a while back. Wright’s not around anymore.”

“So who was on third when Soto was in right?”

“Baty was on third, mostly. And sometime Vientos.”

“But Baty and Vientos aren’t on third now?”

“Nope.”

“So is it right to say they’re not around anymore?”

“No, they’re around.”

“Baty and Vientos are around?”

“Correct.”

“So what do they do if they’re not on third?”

“I dunno.”

“I thought you said I dunno is in right.”

“What I said is I dunno who’s in right.”

“Which means it’s not Soto.”

“Right.”

“Right as in correct?”

“Right.”

“So, just to make sure, you say Soto is now in left?”

“Right.”

“Please just say correct.”

“Correct.”

“And when I asked you who’s in right for the Mets, you said I dunno?”

“That’s what I said.”

“So they still have Soto?”

“For a long time. Unless he opts out.”

“Doesn’t Soto have a contract?”

“Every ballplayer has a contract.”

“Doesn’t the contract say Soto will be a Met for the length of the contract?”

“Correct. It’s a very lengthy contract. Fifteen years.”

“That is a long time.”

“Correct. But he can opt out after the fifth year if certain adjustments aren’t made to his satisfaction.”

“Then it’s not a fifteen-year contract.”

“It is. It just might last not last longer than five years.”

“But he’s a Met right now?”

“Correct.”

“And he was the Mets’ right fielder last year.”

“Correct.”

“So why isn’t Soto still in right?”

“So they can put somebody else out there.”

“And who would that be?”

“I dunno.”

“Which you say is not a peculiar name for a ballplayer, even on the Mets.”

“It’s still a peculiar name, but it’s not the name of the Mets’ right fielder.”

“So who is the Mets’ right fielder?”

“I dunno.”

“When will the identity of the Mets’ right fielder become clear?”

“Later.”

“How much later?”

“Later this Spring.”

“That’s a long way away.”

“Not really. Spring has already started.”

“No it hasn’t. There’s like two feet of snow on the ground.”

“Not where the Mets play.”

“But the Mets play in New York.”

“The Mets don’t play in New York in the Spring.”

“Which this isn’t.”

“But it is. The Mets have already played several ballgames this Spring.”

“Did they win them?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It doesn’t matter? How could it not matter whether the Mets win or lose if we’re fans of the New York Mets?”

“Because it’s Spring.”

“It’s not spring — it’s February!”

“Spring starts in February in baseball.”

“You’re telling me that in the dead of winter, when there’s snow covering everything in New York, including the Mets’ home ballpark, that it’s actually spring, and that the Mets are playing baseball, which is something that as Mets fans we really care about, yet it doesn’t matter if they win or lose?”

“Correct.”

“What happens when it’s actually spring?”

“It’s Spring right now in baseball.”

“I mean when it’s spring everywhere.”

“When it’s spring everywhere, the Mets will be in New York.”

“When will that be?”

“Soon.”

“How soon?”

“Late March.”

“It’s still cold in late March.”

“It’s baseball season in late March.”

“But I thought baseball was the summer game.”

“It says here that baseball starts in New York in late March.”

“Where does it say that?”

“Here. On the official schedule.”

“Can you hand me the official schedule the Mets print?”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“They don’t print it anymore.”

“So what are you looking at?”

“My phone.”

“They don’t have a schedule that fits in your pocket?”

“They put it on phones. They figure there’s one in everybody’s pocket.”

“I see. So I have to look on my phone if I want to see when the Mets play?”

“Correct.”

“OK, I’m looking on my phone, and I see that like you said the Mets play in New York in late March.”

“Correct.”

“And that on the first day they play in their home ballpark, they’ll be giving out schedules.”

“Correct.”

“But you said they don’t print them anymore.”

“They don’t. Except on magnets.”

“So I can just pick up a magnet that has the schedule on it?”

“Only if you go to the game on the first day. Everybody gets one.”

“What if I can’t go to the game on the first day? What if I go on the second day?”

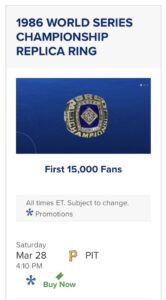

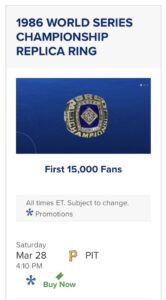

“On the second day they’re giving out replica 1986 world championship rings.”

“That sounds great! Maybe I’ll go to that game.”

“If you want a ring, you have to be one of the first 15,000 fans.”

“One of the first 15,000 fans to what?”

“One of the first 15,000 fans to go to that game.”

“How many people might go to that game?”

“Maybe 40,000.”

“Aren’t all 40,000 going at the same time?”

“They’re all going to the same game, but they each enter the ballpark at different times.”

“And only 15,000 get replica 1986 world championship rings?”

“Only the first 15,000.”

“So if I’m holding a ticket, how would I know if I’m gonna be one of the first 15,000?”

“You won’t be holding a ticket.”

“What if buy a ticket?”

“You can buy a ticket, but you can’t hold a ticket.”

“Don’t the Mets sell tickets to their ballgames?”

“They do. Look on your phone.”

“I see. Whoa, get a load of those prices.”

“Oh, they’ll take your money in exchange for a ticket. But the ticket goes on your phone.”

“So my phone has to be one of the first 15,000 phones inside the Mets’ ballpark?”

“Only if it has a ticket on it.”

“Yet there are no guarantees I’ll get a ring?”

Start bundling and lining up now. “Your best bet to get one is to line up early outside the Mets’ ballpark.”

“That will assure me a replica 1986 world championship ring?”

“Only if 15,000 people didn’t line up before you.”

“So I have to line up really early?”

“Correct.”

“Outside?”

“Correct.”

“In late March in New York?”

“Correct.”

“Where there’ll likely still be some of this snow on the ground?”

“Correct.”

“To go to a thing that I already paid for?”

“Correct.”

“To get a thing I might not get if 15,000 other people decided they wanted to line up even earlier?”

“Correct.”

“And if I don’t get the ring, I get what?”

“You get to see the game.”

“Because I have a ticket.”

“Not technically. But it’s on your phone.”

“OK, let’s say I’ve bought a ticket after looking at the schedule on my phone, and the ticket is on my phone, and I’ve decided to stand outside in late March in New York really early to get my replica 1986 world championship ring, which will be given to only the first 15,000 people…by the way, why don’t they hand one to everybody?”

“Because it says on the schedule they don’t.”

“Can you hand me the schedule where it says that?”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s on your phone.”

“Right….”

“He won’t be playing. He’s not around anymore.”

“Don’t confuse me about that again. I just want to know that if I go on the second day the Mets are home, I might not get a ring, but I will see a ballgame.”

“If it doesn’t snow. It’s going to be in late March.”

“But if it doesn’t snow, the Mets will play a ballgame.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be on first?”

“Polanco.”

“Who’s not a first baseman.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be on third?”

“Bichette.”

“Who’s not a third baseman.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be in left?”

“Soto.”

“Who wasn’t a left fielder last year, but he has been.”

“And will be for a long time probably.”

“Probably?”

“If he doesn’t opt out. And even if he doesn’t opt out, after a while, he might become the designated hitter.”

“Where on the field will I see the designated hitter?”

“Nowhere.”

“So it’s not a real position?”

“Not really, but it is in the ballgame.”

“Who’s the Mets’ designated hitter?”

“I dunno.”

“I thought you said I dunno is in right.”

“By late March we’ll know who’s in right.”

“Who will it be?”

“Maybe Benge.”

“Maybe Benge?”

“Maybe Benge.”

“You’re suggesting I watching a whole bunch of ballgames at once like I would watch a whole bunch of episodes of a TV show I really like to find out who’s in right for the New York Mets?”

“You asked me who’s in right, so I’m telling you, maybe Benge.”

“Do they have doubleheaders for that so I can get multiple games watched at once?”

“Probably not.”

“Well, can you hand me the Mets schedule so I can check?”

“They don’t print schedules.”

“Except on a magnet.”

“Except on a magnet.”

“Which they give to everybody at the first ballgame in New York in late March.”

“Correct.”

“But they don’t print anywhere else.”

“Correct.”

“And they give out other things at other games.”

“Correct.”

“But only to the first 15,000.”

“Sometimes to the first 18,000.”

“To games that might draw more than 40,000.”

“Correct.”

“All to watch a team with somebody who’s not a first baseman on first, somebody who’s not a third baseman on third, last year’s right fielder in left, and in right…”

“Maybe Benge.”

“Benge? At the prices they charge, maybe I can go every now and then, but I’ll probably wait until the weather warms up.”

by Greg Prince on 16 February 2026 4:24 pm Faith and Fear in Flushing celebrates its 21st birthday today, making this the blog that’s legally old enough to drink. And what better way to toast such a milestone than with a lyrical tribute that would seem at home in any saloon situated within the 11368 ZIP Code?

Based strongly on the genius Stephen Sondheim committed to the 1971 musical Follies, and inspired by the voice of survival herself, Elaine Stritch — you mean every Mets blog isn’t? — we’re here to tell you on this February 16 that, as has been the case since 2005…

WE’RE STILL HERE

Faith times and Fear times

We’ve seen ’em all

And, readers dear

We’re still here

Postseason sometimes

Sometimes a drop toward the rear

But we’re here

We’ve whittled magic numbers

Short of zero

Stranded men on third

When short a hero

Seen our stadium disappear

But we’re here

Felt the sting of

Spinal stenosis

But we’re here

L’s put in the books of

Howie Rose’s

But we’re here

We’ve told each other ‘LFGM’

Put too much trust into each GM

Reach contention or just pretend?

Regardless, we would cheer

Team sold to a big financier

And we’re here

We’ve been through Pedro’s, Johan’s, and R.A.’s flair

And we’re here

Harvey Day, Grandpa Bert, and Noah’s hair

And we’re here

We got through departure of deGOAT

Verlander and Scherzer both boarding a boat

Blew taps on our trumpets

As Diaz flew a jet made by Lear

We lived through Luis Castillo

And we’re here

We’ve gotten through Fred and Jeff Wilpon

Gee, that was fun and a half

When you’ve been through Fred and Jeff Wilpon

Anything else is a laugh

We’ve been through Reyes

We’ve been through Cespedes

And we’re here

Flores and Nimmo

Asdrubal Cabrera

And we’re here

Built our hopes up for Dom Smith and Duda

Applauded along when Conforto was Scooter

Held our breath tightly

When they checked Musgrove’s ear

Still, someone said, “Buck’s sincere”

So we’re here

Murph slugged us to a pennant

His ‘D’ then showed ill effect

But we’re here

Black jerseys Friday

Next day City Connect

But we’re here

First we’d lead the league through all those laps

Then came September

And we’d collapse

We blog night after night, season by season

We can’t say for why or for what is the reason

But we’re here

We’ve gotten through

‘Hey, those Mets had quite a run

Thanks a lot for adding some fun’

Or better yet,

‘Sorry the Mets weren’t much fun,

We’ll look you up when they go on a run’

Faith times and Fear times

We’ve seen ’em all

And, readers dear

We’re still here

An Endy catch sometimes

Sometimes au revoir to a Bear

But we’re here

We’ve run the gamut, Aardsma to Zuber

Grab us a 7, cancel the Uber

We got through all of last year

And we’re here

Lord knows, at least we’ve been there

And we’re here!

Twenty-one years!!

We’re still here!!!

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2026 2:47 pm In the 1978 film Heaven Can Wait, veteran L.A. Rams quarterback Joe Pendleton, played by Warren Beatty, is in the prime of his life — “at my age, in any other business, I’d be young” — when he rides his way into an apparently fatal bicycle accident. An escort from above assigned to monitor such activity (Buck Henry) dutifully swoops up Joe to move him along on his celestial journey. Except the QB knew in his bones the accident wasn’t as fatal as it appeared, and therefore heaven really could wait. His assuredness led to this exchange between Joe and the escort’s supervisor Mr. Jordan (James Mason), the elegant gentleman charged with overseeing cloudbound operations.

JOE PENDLETON: I’m not supposed to be here.

MR. JORDAN: But you are here.

JOE PENDLETON: Well, you guys made a mistake.

Even as our collective attention shifts to hamate bones and positional switches reporting to Port St. Lucie in the company of pitchers, catchers, and everybody else, I’ve found myself thinking about that cinematic exchange from 48 years ago, overcome by the idea that someone winds up where he is not supposed to have been sent. I was directed in my mind to those lines and that thought in the aftermath of learning two one-time Mets had died just ahead of the beginning of Spring Training. “One-time” sounds right here. The first man was a Met for precisely a single season. The second of them was one of us for barely more than a month.

The passing that really brought it home was the second, that of Terrance Gore. Terrance Gore was a Met in 2022. He was 34 years old. Four Mets reporting to this very Spring Training are older. No, he’s not supposed to be here. In my heart, no baseball players are supposed to enter this sort of discussion. Because baseball players wind up as human beings regardless of the profession we grew up exalting, they inevitably wind up here, as any person will eventually.

But, if there’s justice, not a person who was 34. Not a Met from 2022 in 2026. Not someone I stood up to applaud on the final night of what is now a mere four seasons ago when he connected for his only base hit as a Met. Terrance Gore wasn’t a Met so he could bat. Buck Showalter brought him in to be his primary pinch-runner ahead of the playoffs. I trusted Showalter to know personnel the way Rocky Balboa trusted Mickey to train him for his longshot bout versus Apollo Creed. Late in Rocky, Mick tells Rock, “I want you to meet our cutman here, Al Silvani.” No further discussion needed, Al Silvani is the cutman. Early in September of 2022, Buck told us Terrance was in for Travis Jankowski, which is to say he would be in for the likes of Daniel Vogelbach and Tomás Nido should such lumbering Mets reach base.

Jankowski had done a fine job as Showalter’s pinch-runner of record before the Mets squeezed him off the 40-man, but Gore was a bona fide baseball celebrity to baseball fans who paid attention to baseball minutiae. Gore, listed as an outfielder, was the entire industry’s pinch-runner of record. He was famous for running for somebody else and getting rewarded for it handsomely, collecting three World Series rings despite rarely batting or fielding. He understood his mission on those championship rosters — the Braves’ in 2021, the Dodgers’ in 2020, the Royals’ in 2015 (when he had the decency to not enter a single World Series game) — was to be speedy in spots that could alter outcomes.

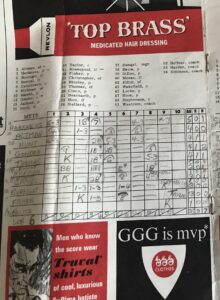

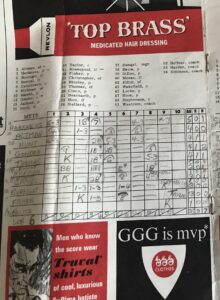

That was Terrance Gore’s role as a Met. He made it into five late-season games as a Met pinch-runner, plus a few others as a defensive replacement. In the bottom of the eight on a Sunday afternoon, as the Mets attempted to sweep away the pesky Pirates, Terrance put on what could be rightly called a pinch-running clinic.

He comes in to run for Nido.

He steals second.

He takes third as the catcher’s throw sails into center.

He comes home on Brandon Nimmo’s short single to left-center.

The Mets retake the lead.

The Mets win the game.

The essence of successful pinch-running in one quick 270-foot trip.

For Game 162 of 2022, Showalter granted Gore an entire nine innings to demonstrate his utility for the impending playoffs. As the starting center fielder, he lined a single into left off Erick Fedde of the Nationals. As baseball fans, we relish jumping to our feet and clapping when a player successfully completes what isn’t his standard assignment. Terrence hadn’t registered a base hit since 2019. It wasn’t his job, but now he had done it in front of us, and we did not hesitate to express our appreciation. We’d only been acquainted with Gore for a month, but we wanted to let him know we liked what he was doing.

The last thing Terrance Gore did, having made the postseason roster, was pinch-run in the second game of the National League Wild Card Series against the Padres. Darin Ruf led off the home sixth by helpfully placing his body between a pitch and the catcher’s mitt. The DH was HBP, and how he’d be PR for. Gore in for Ruf. The Mets were down one in the series and up one in the ballgame. What a perfect situation for a player of Terrance’s skills to make a difference. This was a man who had pinch-run 67 times in regular-season play since coming to the big leagues in 2014, plus eleven more in the postseason with this appearance. He was a specialist and this loomed as a special moment.

Then Nido grounded to second, instigating a 4-3 DP that not even the speediest pinch-runner could upend. Sometimes that’s how the ol’ ballgame goes. Sometimes that turns out to be the last time you see a ballplayer playing ball. Gore, penciled in as designated hitter, would be pinch-hit for when his slot in the order next came around. Buck didn’t have a situation for him in deciding Game Three, the one that eliminated them, and that was the end of Terrance Gore’s Mets career and, as it turned out, baseball career. The Mets wanted to outright Gore to Triple-A. He had the right to refuse and elected free agency. Nobody signed him, and that was that as far as we knew.

Not even three-and-a-half years later, you read Gore has died at 34, reportedly from surgical complications, and you can’t quite fathom it. You never can with ballplayers who were playing for your team just the other year, which might as well be just the other day. Gore is the fifth late Met whose tenure with the club took place entirely in this century, the only one whose breadth of major league experience postdates Shea Stadium. Shea Stadium lingers in the distant enough past that we’re now down to one potentially active MLBer, the as yet unsigned Max Scherzer, who can say he played there. If we mark time by stadia, anything we hear about Terrence Gore lands as relatively current, never mind indisputably recent. The 2022 Mets? I know we just let some of those guys go, but a few are still Mets on the precipice of 2026; Francisco Lindor, Mark Vientos, and Francisco Alvarez were in the starting lineup alongside Gore on October 5, 2022. Citi Field? It’s where we’ll be focusing our attention at the end of March. This March. I was just there in September for Closing Day, just as I was just there in October of 2022 for Terrance Gore’s lone Met hit.

If we imagine our lives as following some kind of path, à la Heaven Can Wait, we could do worse for a roadmap than a baseball diamond. Home to first. First to second. Second to third. Third to home. It may not work that way in life, but it’s kept baseball humming in fine fettle. Terrence Gore didn’t even have to go home to home around the diamond most games. He’d usually start at first base. He was in as a pinch-runner to pick up for the guy who found his way there from home plate. Baseball allows this, somebody fast helping out somebody who’s not. That was what Terrance Gore did so well that teams contending for a title sought him out and showed their faith in him to do it some more.

The bulk of Terrance Gore’s baseball career was about getting from only first to home as fast as possible. By that measurement, somebody owes this man an extra ninety feet.

Before the loss of Gore and one other Met this February, there were a half-dozen far older Mets who died between the end of the 2025 season and the turn of the calendar to 2026: infielders Sandy Alomar, Sr. (81), Larry Burright (88), and Bart Shirley (85); outfielder George Altman (92); first baseman Tim Harkness (87); and starting pitcher Randy Jones (75). I’m also compelled to mention reliever Bill Hepler (79), who died in August without us taking a moment to note his passing. Those were seven Mets from what is unquestionably a long time ago. Six of them were Mets in the 1960s, a decade that hasn’t been active for more than fifty-six years. Alomar and Jones are the only ones I personally remember as major leaguers, and my instinct is to say I’ve been watching baseball almost forever.

Yet it was too soon for all of them to go, because baseball players became baseball players before the primes of their lives even began, and the people who cared most about them were kids whose lives had barely begun. We, those kids, get older and if we think of baseball players from our youth, we don’t see men who’ve aged into their so-called golden years. We see the athletes. We see the Mets. We see ourselves, from the inside out, viewing them as Topps intended. We don’t know it at that age, but those are their own kind of golden years, and a baseball player’s name is license to revisit them any time it occurs to us.

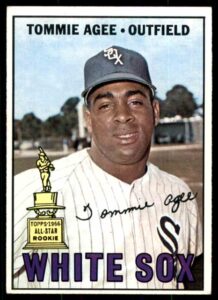

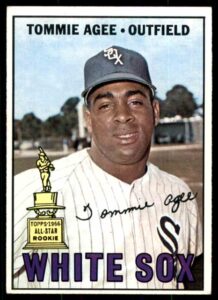

If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game! If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game!

Baseball players being human beings in their spare time precludes actual immortality. But isn’t it fun to remember the eternal excitement they evoked when we weren’t particularly judgmental, especially when they wore the uniform of our favorite team? In that respect, Pavlov’s Intro for us of a certain age was surely the highlight montage that ushered onto Channel 9’s air Mets games during the heart of the 1970s, when Shea continued to stand tall. At first sight and sound of that montage, the young Mets fan heart would race and the young Mets fan mouth would salivate. The Mets skyline logo spun into place. The instrumental version of “Meet the Mets” blared. Mets players were in action, and I mean action, with one film clip succeeding another in rapid fire procession.

A Met swinging. A Met throwing. A Met leaping. Finally, a Met sliding into home and scoring to the greatest of musical scores, all in glorious grainy color (or black & white, depending on the TV set available to you). Edits were made to delete or incorporate this Met or that as roster revisions necessitated, but every last Met shown was clearly intrinsic to Team Highlight…except, maybe, for one Met who made the montage one year without ever truly fitting within its pulsating confines.

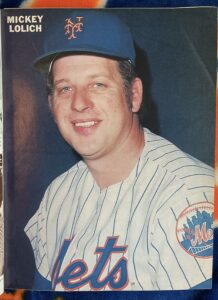

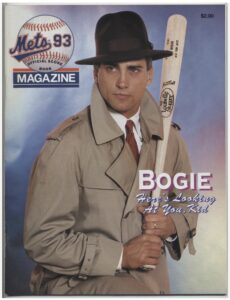

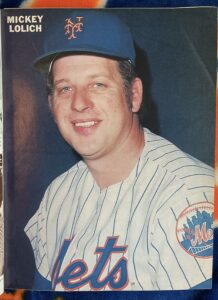

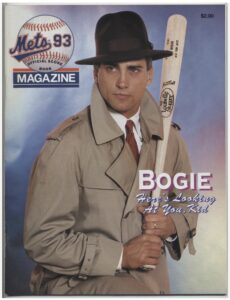

Before Warner Wolf made doing so fashionable, Mickey Lolich went to the videotape. Mickey’s snippet, spliced into the 1976 introduction, was not on film like everybody else’s. He had never been properly filmed as a Met, thus WOR was compelled to insert a frame or two from the telecast of his first start in April, lest the station stand accused of not keeping current. I wouldn’t say it portrayed the lefty import in action. Lolich, the only new Met on the Shea Stadium scene when that season commenced, stood on the mound for an instant. Maybe he went into his windup. I don’t remember if he threw a pitch. In the mind’s eye, he was just kind of there until we could return to the Mets who looked like they belonged on the Mets.

How’s that for a Met-aphor, vis-à-vis “I’m not supposed to be here”?

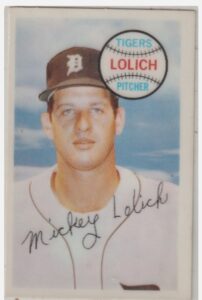

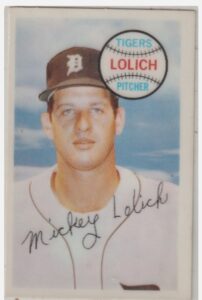

Mickey Lolich was the first Met to die this February, a couple of days before Terrance Gore. Lolich was 85, that age when you’re not bowled over by such a bulletin, even if it regards a ballplayer you remember well from when you were 13. With news of his passing, the lefty was acknowledged far and wide in baseball circles as one of the great Detroit Tigers. I heard about his death, and I’ll confess to remembering him near and narrowly as a New York Met from central miscasting — a dependable source of on-field personnel for us through the years. Listen, we’ve had loads of players who just passed through, plenty of others who didn’t live up to their established reputations upon becoming Mets, quite a few who were on the irreversible downside when they donned our duds (former Cy Young winner Randy Jones, for example). The inclination is to tick off a dozen disappointments who have spanned the decades, as if to show each other our rooting scars and congratulate ourselves on our perseverance.

Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich. Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich.

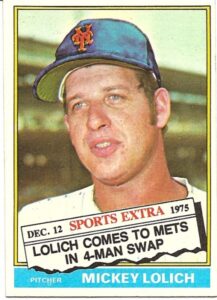

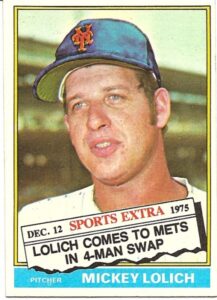

On December 12, 1975, the Mets traded Rusty Staub and minor leaguer Bill Laxton to the Tigers for Mickey Lolich and minor leaguer Billy Baldwin. There, I thought, went so much that was fun about 1975, while simultaneously inferring that 1976’s version of the Mets was diminished before it began. No 12-year-old had ever been as wrapped up in an also-ran as I was in the 1975 Mets, and about half my goodwill had just been tossed aside. Rusty Staub, besides being Rusty Staub to us ever since we traded for him in 1972, had just reached one of those heretofore unreachable statistical stars. Our fixture in right field became the first Met to crash the 100 RBI barrier in ’75. It took fourteen seasons for any Met to drive in triple digits. It took fewer than three months for Mets management to decide such a skill set was disposable. Surprise, surprise, M. Donald Grant didn’t want to keep around a beloved veteran star at the top of his game, one whose strong personality apparently clashed with his idea of how a player should act (which is to say thankful to the opportunity to call Mr. Grant his employer). Had Rusty made it through five years as a Met, he could veto a trade. Player empowerment gave Grant the worst kind of rash. It therefore became GM Joe McDonald’s job to ship Staub somewhere else ASAP and get something of value in return.

Mickey Lolich was a name. In the American League, his name had been synonymous with 2,679 strikeouts, the most recorded by any lefthanded pitcher in baseball history as of the Bicentennial; three complete-game victories in the 1968 World Series, culminating in his besting Bob Gibson on two days’ rest to take Game Seven (not to mention a home run he hit off Nelson Briles in Game Two); and a pair of 20-win seasons a few years later. Had Vida Blue not been so spellbinding over the first four months of 1971, Lolich could have claimed he was a victim of Cy Young robbery. As was, Mickey, as runner-up, won more games than anybody in the majors in ’71 (25), started more games than anybody in either league (45), struck out the most batters in baseball (308), and posted an innings total 42 frames beyond that of any counterpart (376). He followed all that with a 22-14 mark in 1972, pitching the Tigers to the AL East title and doing his damnedest to get them back to the Fall Classic. In an ALCS recalled today mainly for Bert Campaneris flinging a bat at Lerrin LaGrow in Game Two, Lolich pitched into the eleventh inning of Game One, only to take a hard-luck loss, and was no-decisioned despite going nine innings and giving up a lone run in Game Four.

Jesus, that guy was good. And you would have loved to have that guy from 1968 or 1971 or 1972 on the Mets. What a highlight player he would have been. As 1976 approached, those peaks were fading fast in time’s rearview mirror. Lolich’s last two years as a Tiger saw him lose 39 games, albeit for a team that was altogether past its late-’60s/early-’70s prime. Numbers unavailable to the baseball-consuming public in 1975, particularly his Baseball-Reference WAR of 4.0, indicate he was done no favors by pitching for the 102-loss Tigers. On the other hand, his having turned 35 was a matter of public record. All those innings on all that Lolich (bulky would be a kind description) had to have taken a toll after so many years.

At his age, in any other business, he’d be young. In 1976, in baseball, he was getting on.

Yet the Mets tried to treat him as a get. Convinced of the durability of their Kingman-Unser-Vail outfield, GM Joe McDonald figured a lack of offense, even sans Staub, wasn’t an issue that was going to bedevil the Mets. What the team fronted by Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, and Jerry Koosman needed to do, according to McDonald, was trade its most reliable stick for another arm. “One of the reasons we didn’t win last year,” McDonald rationalized upon announcing the trade, “is because we didn’t have a solid No. 4 starter. Now we go into a town for a three-game series, and the other team knows they are going to face one of the four in every game.” Too much pitching is rarely any team’s problem, but whither the offense? Whither the 105 RBIs that just went out the door? Whither the foot Mike Vail broke playing basketball during the offseason? Joe McDonald plans, the entity Mr. Jordan works for laughs.

Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal. Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal.

His introduction to the Mets nonetheless represented a shock to his Detroit-defined system, and it was made no smoother by a Spring Training that was delayed past St. Patrick’s Day thanks to an owners’ lockout. Among an informal gathering of stretching and tossing Mets, Cardinals, and Pirates in St. Petersburg, the southpaw admitted nobody in this league was familiar to him, not even on his own team. Of longtime catcher Jerry Grote, who was as much a fixture to the Mets’ staff as Bill Freehan had been to the Tigers’, Lolich told Newsday’s Bill Nack, “If he walked up to me now, I wouldn’t know who he is.”

Yet here came Mr. Lolich, wearing a boxy Mets jersey, starting the third game of the new season. Seaver won on Opening Day. Matlack threw a 1-0 shutout the second day. Lolich couldn’t maintain the momentum, lasting only two innings. He’d made two errors and had given up three Expo runs on one of those trademark windy April Shea afternoons. His spot in the batting order came up in the bottom of the second with the bases loaded and two out. Rather than let Lolich take his first swings since pre-DH 1972, new manager Joe Frazier sent up John Stearns to pinch-hit. Stearns flied out. With the Mets leaving fourteen runners on bases, Frazier and Lolich were both on their way to their first National League losses.

Things would get intermittently less horrific. It took four starts for Mickey Lolich to earn an NL win, but he did it in style on April 26, going the distance and striking out nine Braves, while working harmoniously with Ron Hodges, who, like Grote, he’d eventually met. His wins legitimately impressed. A complete game at San Francisco in mid-June. A shutout over St. Louis as June ended. Another whitewashing when Atlanta returned to town right after the All-Star break. On August 8 in Pittsburgh, as Hurricane Belle bore down on New York, Mickey withstood storm clouds of his own. He gave up eight Pirate hits, walked one Buc, struck out nobody, yet remained on the mound all nine innings in posting a 7-4 victory. It was the third and last time a Met pitcher ever won a complete game with zero strikeouts, and it was done by a pitcher who, entering that season, had struck out more batters than any pitcher in baseball history besides Walter Johnson and Bob Gibson. “Sometimes,” the lefty explained in April, “I’ll change my style of pitching two or three times a game.” Clearly, the veteran could put his versatility to optimal use.

Lolich was the personification of that little girl with the curl cliché Ralph Kiner loved invoking. When he was good, he was very good. Sometimes he’d be more than pretty good but his batters weren’t up to snuff. Lolich threw eighteen quality starts — at least six innings pitched, no more than three earned runs allowed — yet the Mets lost nine of them. Come summer, Bob Murphy was regularly using the word “snakebit” to describe Lolich’s season. Sometimes the bad-luck serpents couldn’t be blamed, as the pitcher who turned 36 on September 12 simply wasn’t able to keep pace with Seaver, Matlack, or soon-to-be Cy Young runner-up (to Randy Jones) Koosman. A fourth starter, no matter how accomplished, tends to perform like a fourth starter. Lolich’s 3.22 ERA wasn’t the sparkling stuff usually posted by Met aces of the day, but it probably deserved better than an 8-13 won-lost record on a third-place club that went 86-76. His ERA+, a metric conceived decades later to provide context for how a pitcher performs among all of his peers, was 101, or ever so slightly above average.

As a 13-year-old Mets fan in 1976, recently Bar Mitzvahed and everything, I’d like to think I had reached the age of reason. I could reason that though Lolich couldn’t keep his earned run average below three and couldn’t compile more wins than losses, that he was not bad. I kept telling myself that. He’s not Seaver, and he’s no longer the guy who gave Vida Blue a run for his money, but he’s OK. He can’t help it if they don’t score for him. And he can’t help it if we never should have traded Rusty Staub. Yeah, I still missed Rusty Staub. Did any Mets fan not? The group of Tigers Rusty went to weren’t dramatically better than the set Lolich left, but they sure seemed to be a lot more fun than the 1976 Mets. The main reason was Mark “The Bird” Fidrych talking to the ball before throwing it past batters en route to a literally sensational 19-9 year, but don’t overlook the joie de vivre provided by Detroit’s new right fielder and sometimes designated hitter. Staub played 161 games for the Tigers, drove in 96 runs, and was elected to the AL All-Star team by discerning fans everywhere. If Rusty missed us like we missed Rusty — both in the affection and run-production sense — it didn’t show in his stats.

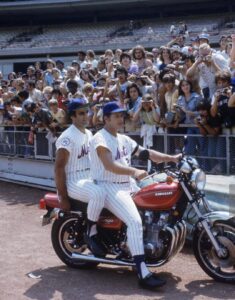

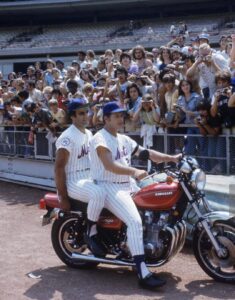

Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base side warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing. Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base side warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing.

With a year remaining on his contract, Mickey Lolich let the Mets know whatever they were planning for 1977, they could do it without him. The native Oregonian never stopped missing Michigan. It was home to him and his family. New York was a yearlong business trip. Lolich elaborated on his exit strategy for the Daily News in December of ’76:

“The season was not fun. On the days I wasn’t pitching, life wasn’t fun. I was very happy with the Mets. They were some of the finest players I’ve ever been with, and I got along well with the front office. I was disappointed in my record because I pitched better than that. So did Tom Seaver. People ask, what was wrong? Nothing was wrong. But the Mets definitely need a power hitter to help Dave Kingman.

“And the first two months were difficult with the people ridiculing me and belittling me. I got letters and heard them telling me they wanted Staub there instead of me. Sure, it reflects on me. I’ve been playing in the big leagues for 14 years. Now I want to be home.”

With that, Mickey Lolich was retired. Then, after his Mets contract officially expired, he unretired, filed for that newfangled free agency, and gave pitching one more shot, this time out of the bullpen as a reliever for the San Diego Padres, farther from Michigan than New York was. He toed the Shea mound once in his two Padre years, on August 17, 1978, throwing three shutout innings and notching his first (and only) National League save in support of Gaylord Perry’s 260th career win. Per Don Williams in the Star-Ledger, Mets fans booed Lolich when he entered he game, booed again when he batted, and cheered when he struck out. “Sure I expected it,” the ex-Met said of his reception. “That’s New York.”

At the end of 1979, Lolich decided he was done being a big leaguer for real. Back to Michigan he went for good, occasionally receiving the “where are they now?” treatment as the pitcher who went from putting up zeroes to turning out doughnuts at Lolich’s Donuts & Pastry Shop in Lake Orion, Mich. Hockey great Stan Mikita owned a place like that in Wayne’s World, but his establishment was fictional. Lolich’s new line of work was genuine. The Times visited him when the Tigers made the World Series in 1984, stressing how earning 217 major league wins had been Lolich’s then, while baking “400-dozen doughnuts a day” accounted for his now. Tensions were dissipating between him and the team he was remembered succeeding for, and, as the years went by, the idea Tigers ever traded him away must have seemed as absurd in those parts as it is in our neck of the woods that the Mets felt the need to rid themselves of Rusty Staub.

For the rest of his life, doughnuts or no doughnuts, Mickey Lolich was introduced; referred to; and thought of first, foremost, and practically exclusively as MVP of the 1968 World Series, one of the all-time great Detroit Tigers. However he spent his 1976 was just some fine-print detail. Lolich would make his final appearance at Comerica Park in 2023 as part of a pregame 55th-anniversary celebration of the championship his left arm made possible. He and a handful of his ’68 teammates stuck around to take in a promising performance from emerging Tiger ace Tarik Skubal. Skubal struck out nine, a fairly Lolichian total, but the kid on the verge of back-to-back Cy Youngs went only five innings. They were scoreless, but there weren’t that many of them. Afterward, the young lefty berated himself for not lasting seven — not nine, but seven. When Tarik tossed his first complete game in 2025, it left him 194 shy of Mickey’s career total.

Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!” Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!”

Yes, it’s how we felt about Rusty Staub, and were bound to feel the opposite of when we encountered anybody who got in the way of our devotion to and adoration of Le Grand Orange. Nothing personal, Mickey. That’s New York, too.

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2026 1:48 pm A Mets fan walks into an Applebee’s. That’s not a setup to a quip. It actually happens once a year that I know of, with me as the Mets fan. Applebee’s menu tends to shake out a bit on the salty side for my tastes, but salty is something I’ll never be if somebody is kind enough to take or, more accurately, send me there on the house every January.

My wife’s birthday, you see, was last week, and when my wife’s birthday is nigh, my sister and her husband never fail to send us a generous gift card for Applebee’s, a national chain restaurant conveniently located to where we live. Its proximity is its primary appeal to us. Barely having to drive and not having to pay equals eating good in the neighborhood. More partial to bringing in than dining out, we don’t usually take advantage of the hospitality on-premise, but this January we made an exception. We went to our town’s Applebee’s for lunch last Wednesday. It was the same afternoon the Mets introduced Bo Bichette to the press; the day after the Mets acquired Luis Robert, Jr.; a few hours before the Mets traded for Freddy Peralta. This is how a Mets fan who walks into an Applebee’s has come to mark time this January.

And who should greet Stephanie and me practically inside the door at Applebee’s but Pete Alonso? Specifically, a substantial color photo of the Polar Bear that graced the bulk of a wall adjacent to the hostess station. With each index finger raised in the direction of the crowd, Pete appeared to be celebrating one of his franchise-record 264 home runs. The image must have gone up since last January, the last time I was in there to pick up our gift card’s worth, because had it been up the year before, I would have noticed it. And had this visit been before December of 2025, I would have kvelled without qualification that a name-brand casual dining establishment — or any establishment, really — was devoting a place of prominence to the longtime signature star of the Mets.

Well, this is awkward. Now, in January of 2026, Big Pete was just another piece of flare that a joint like Applebee’s mandates to imply one of its outlets is suitably sporty and righteously regional. They also have lots of pictures of area Little League and high school athletes up as well. I didn’t check to see who among them has since graduated. I do know Alonso works in Baltimore these days.

Pete will always be a Met icon. A decade from now, that picture, if corporate hasn’t mandated its removal, will stand as a pleasant reminder of a player who did great things for the nearby team and was well-loved while doing it. A sizable portrait of Pete Alonso by then will hit like a sizable portrait of, say, Cleon Jones now. If Cleon was the de facto face of our Applebee’s, you think I’d ask to speak to the manager and request we not be shown somebody who finished his career on the South Side of Chicago, nowhere near our local Applebee’s? Yet stepping right up to greet Pete was not what I was planning on doing last week. I was having a hard enough time getting to know who’s actually on the Mets at the moment.

I wasn’t planning on this, either, but I now root for a team that features Bo Bichette, Luis Robert, Jr., Freddy Peralta, and, if his minor league deal amounts to anything, Craig Kimbrel. Fine. Great. Maybe wonderful. But I wasn’t planning on it. I’ve certainly known their names and something about their games. I didn’t know they were Mets. They weren’t until very recently. Nevertheless, here they come into my life and your life, along with some other fairly familiar ballplayers who played elsewhere in years past. To some extent, that’s every winter on the verge of Spring. Some winters it feels organic. Some winters it feels transformative in a welcome way. This winter it feels almost random. If Leonard Nimoy were still hosting his syndicated program, he’d be in search of context for these Mets.

The Mets as we knew them — the Mets with whom we lost patience on the road from 45-24 to 38-55 — ceased to exist in the segment of the offseason that bridged 2025 and 2026. Then there were a few weeks when there didn’t seem to be much to the Mets at all. A lot of deletion. Sporadic addition. Tempting as it was to lose patience with the lack of progression, that was OK. It was late December and early January. There was no baseball yet. Somebody would be playing as Mets by the end of March.

The Mets as we know them at present, at least the Mets to whom we are being introduced these days? I don’t know. I really don’t. I guess that’s OK, too. Even it isn’t, it’s going to be.