It’s nice to know who you are, even if you don’t always buy into it, even if who you are keeps on changing. For example, per a request made here [2] several weeks ago, Andre Dawson will be going into the Hall of Fame as a Montreal Expo [3], making thousands of dispossessed ‘Spos fans (if not Dawson [4]) very happy. For history’s sake — or Cooperstown’s sanctioned version of it — we know Andre Dawson as an Expo.

Then there’s a certain edifice in South Florida, close to the Dade-Broward border. It is now known as Sun Life Stadium [5]. What’s Sun Life? My first guess was a tanning oil concern. My second guess was a marketer of vitamins that were once subject to government recall. Two strikes, so I looked it up: Sun Life is a Canadian insurance concern. Why is a Canadian insurance concern’s name on a stadium in South Florida just in time for the football game that will be played there February 7 when Andre Dawson is reluctantly wearing the cap of a Canadian team for whom he actually starred? I assume money is involved. Sun Life Stadium was, for about twenty minutes, Land Shark Stadium. Before (and after) that it was Dolphin Stadium. Prior to that? Working backwards, it was Pro Player Stadium, Pro Player Park (quite the distinction from Pro Player Stadium) and, when the Florida Marlins moved in there in 1993, Joe Robbie Stadium.

The Marlins are scheduled to move out in 2012, but I get the idea that the building is trying to tell them to get lost already. I’m sure their mail already has, several times over.

Honest to Gosger, who besides those who are paid to do so is going to call it Sun Life Stadium? We like to call it Soilmaster Stadium [6] since there are sacks of the stuff [7] visible in the Mets’ dugout every time the Mets play there. Funny how they found the time to change the name of the stadium every few weeks but they never could build a proper storage shed. But when we’re not mocking the home of the Fish, I still instinctively refer to it as Joe Robbie. Joe Robbie [8] was a guy, not a company. Joe Robbie Stadium is a better identity [9], no matter what whoever makes these decisions nowadays thinks.

This brings us to the Mets, who will be playing in Mets caps (several variations, per usual) at Citi Field (name holding surprisingly [10] steady after one fiscal year) in 2010. While the Mets can boast of bits of stability where those sorts of ancillary issues are concerned, it seems their identity is up for grabs. Let’s hope it is, because the one being built on their behalf at the moment is not one you’d seek.

As if you hadn’t noticed.

At the slightest provocation, a well-known baseball columnist [11] or two [12] will remind us that the Mets look bad in winter and are likely to get worse come spring. Response from there, whether it be online, on the air or deep within the souls of most every Mets fan paying attention, tends to echo or expand upon the broader points of these scathing critiques — albeit with a modest dose of “everybody stop being so negative!” backlash to the backlash put forth in the name of loyalty or, perhaps, self-preservation. With every wave of anxiety washing over Metsopotamia, we form an ever less impressive identity for our Mets. If they were in a police lineup, surely we’d finger the most hopeless, hapless, clueless group of suspects and declare, “THAT’S THEM! WE’D RECOGNIZE THAT DIM-WITTED EXPRESSION ANYWHERE!”

We wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. But we wouldn’t necessarily be right.

The penultimate episode of my favorite dramatic series ever (television series, I should clarify; my favorite dramatic series ever was the ’99 NLCS [13]), Six Feet Under, was entitled “Static”. Why static? Take this exchange between Claire, the grieving youngest daughter of the Fisher family and Nate, her recently deceased brother over whom she is grieving and thus talking to only in her imagination:

Nate: Stop listening to the static.

Claire: What the fuck does that mean?

Nate: Nothing. It just means that everything in the world is like this transmission, making its way across the dark. But everything — death, life, everything — it’s all completely suffused with static. You know? But if you listen to the static too much, it fucks you up.

This is, for Mets fans, the season of static. There’s no baseball and there’s no movement toward perfecting a baseball team once there is. There’s only, you know, re-signing Fernando Tatis [14] and generating buzz about Josh Fogg [15]. It’s not substantive to us. Substance is a pool of Mets making us anticipate Opening Day. It’s a 25-man roster coalescing into a contender. It’s superstar center fielders healing rather than being subject to lawsuits and such.

Little wonder the Mets’ identity is frayed. No wonder the Metsosphere is continuously and maybe justifiably staticky [16], jittery [17] and expressing discontent [18]. We are, by nature, a gaggle of nervous crosstalkers when we don’t have an actual season to dissect. Right now it’s all nervous crosstalk for Mets fans. We, collectively, remind me of the middle-aged ladies who’d set up card tables in front of somebody’s cabana at the beach club to which my parents belonged when I was little. (That’s the Sun Life I remember.) Those ladies indulged in nervous crosstalk, too, just like us. All we’re missing is four floppy hats, a carton of Tareytons and a few hands of canasta.

Just walking by them made me jittery, and I was only six.

We don’t have any Mets games right now, so naturally we’ll look at anything Mets-related on the card table and tear into it like it’s the Slenderella platter the cabana boy might bring these ladies who lunched. We look at the Mets not signing a passel of seemingly suitable pitchers and we’re pretty sure that all we’re gonna be left with to start the season is a scoop of cottage cheese, a cling peach slice and a naked hamburger patty. We have pitchers who have regressed, pitchers who are rehabbing, pitchers who loom as ridiculous…and, as if to save time in rounding up all three, Oliver Perez. Even if we expect Johan Santana to be fully recovered and routinely wonderful, that makes the projected rotation no better than Exclamation Mark and the Mysterians…with the lot of us poised to cry 2010 tears.

No, as Matt Artus implies at Always Amazin’, the state of our union [19] is far from robust. And yeah, I get why confidence in anyone responsible for organizing or comprising these Mets is not in abundance. I don’t care for the piling on by the Rosenthals and Klapisches (and idiots with undeserved platforms [20]), but I’m also not ready to sell backlash to the backlash. I didn’t buy into the 2009 Mets going into last season when all components seemed to be functioning, and I didn’t take comfort in their briefly splendid record before everything went to health — not when fundamentals-free baseball [21] was running rampant. I don’t have a lot of faith in the 2010 Mets at this juncture either, whatever their best-case potential [22]may be; it’s been a while since I’ve seen a Met case acquit itself as a best case. There’s nothing wrong if your discernment leads you to a “negative” assessment of this team’s short- and long-term prospects if, in fact, you honestly assess the Metscape and detect that things are irredeemably awry.

However, they may not be.

This is where I’d love to provide insight and comfort as to why this will be a fine, fine season after all. Alas, I’m afraid I don’t have a silver bullet emblazoned with some secret statistical formula that will prove we are not doomed to mediocrity in 2010. What I have — besides no proof that we are inevitably doomed to mediocrity — are a couple of bits of encouraging precedent, neither of which amounts to Pollyannish positivity, each of which is likely irrelevant, but both of which are better than nothing.

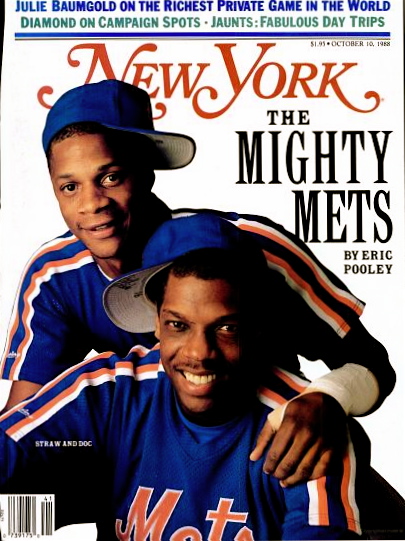

We were supposed to suck in 1984. It was habit, even if I personally didn’t see it that way that winter, despite the spirit-dampening loss of Tom Seaver [23] to the White Sox. The year before we had managed to accumulate at least half a lineup that didn’t suck: Hernandez at first, Brooks at third, Wilson in center, Strawberry in right. George Foster had recovered from his mighty plunge in 1982 to knock 90 runs home in ’83. Junior Ortiz, Brian Giles and Jose Oquendo all showed flashes. No, I thought, we won’t suck. But I didn’t see us jumping all the way from last to second with a pleasant summer’s stayover in first. I didn’t see Dwight Gooden’s medical degree. I didn’t know what a difference Davey Johnson [24] was going to make or how Mike Fitzgerald, Wally Backman and Ron Gardenhire would be upgrades over Ortiz, Giles and Oquendo at catcher, second and short.

I chuckled a bit the other day as I read a post on the prolific and addictive Mets Police site wherein our busy blolleague Shannon Shark bemoaned the Mets’ lack of a brand [25], which is a cousin, I suppose, of identity. “In the mid ’80s,” the Police chief wrote, “there was a swagger. I think Keith Hernandez personifies it. If you throw another fastball I will punch you. There was a swagger. It was very New York.” I chuckled because, while I don’t think that’s an inaccurate portrayal of those times, winning is what gave the Mets their swagger, their punch, their brand, their whatever. It’s amazing what winning will do for you. When you win, you don’t need an identity. You’re a winner. Everything else is subtext. The mid-’80s Mets started out in 1984 as perennial doormats. They rose from there. Next thing you know: swagger.

The Mets were going to suck in 1984, according to conventional wisdom. Or, according to mine, they couldn’t help but be somewhat better but probably not all that great. We were all wrong. They were an unforeseen contender, the best kind.

We were supposed to suck in 1997. It was also habit. I saw it that way, too. We were the Mets who fell below .500 in 1991 and stayed there for six seasons. There were no big free agent signings after 1996. There was also no sense of competence percolating à la 1984. None of the pitchers on whom the Mets had counted in ’96, the instantly mythic Generation K trio of Izzy, Pulse and Paul, would be available by Opening Day (or, as it turned out, September). Three position players compiled awesome 1996es, yet even with Todd Hundley, Lance Johnson and Bernard Gilkey producing at their highest levels fathomable, we still lost 91 games. What new dismay awaited us next?

Little to none, it turned out. Bobby Valentine, who took over for Dallas Green at the tail end of the previous season, found guys he and he alone counted on. Or maybe GM Joe McIlvaine hadn’t found him anybody better and Bobby learned to cope. However it came to be, journeyman Rick Reed emerged as a superb second starter; overlooked ex-Rockie Armando Reynoso contributed win after win in the early going; the preternaturally obscure Brian Bohanon picked up significant slack after Reynoso succumbed to injury; guys who projected as Tides if anything at all — Matt Franco, Jason Hardtke, Luis Lopez — appeared from almost nowhere to fill in ably. If you were told that this collection of nowhere men would fashion a key to success, you would have scoffed as you’d been conditioned to since 1991.

But Valentine’s sweethearts were difference-makers. As were Edgardo Alfonzo, who was promoted from utility player and emerged as one of the best third basemen in the league once Bobby entrusted him with the job; and Butch Huskey, woefully miscast at third, but utterly useful in right; and a salvaged John Olerud, deteriorating in Toronto, resurgent in Queens; and heretofore unspectacular Bobby Jones, suddenly among the best pitchers in baseball for three months; and Carl Everett, who, for a time, harnessed his talent and plugged whatever hole developed in the outfield.

Funny how Valentine’s hunches, calculations and strategies worked out in light of what didn’t click. Hundley put up good if lesser power numbers compared to 1996. Gilkey slumped almost endlessly. Johnson was injured and eventually traded. The previous year’s great outfield hope, Alex Ochoa, took a nosedive. A herd of relievers — Toby Borland, Ricardo Jordan, Barry Manuel, Yorkis Perez — imported to improve upon the smoldering wreckage wrought by Jerry DiPoto, Doug Henry and other best-forgotten 1996 perpetrators actually proved worse in the clutch than their predecessors. Plenty of the things you would have figured had to go right for the ’97 Mets to be any better than the ’96 Mets didn’t occur…yet the ’97 Mets were way better than the ’96 Mets. They broke the franchise’s six-year losing streak, won 88 games and competed tenaciously for the Wild Card into September [26]. As in ’84, a new and happier era of Mets baseball commenced.

Nobody saw it coming.

Neither of these heartwarming examples guarantees anything for the 2010 Mets. We don’t have a new or almost-new manager implementing a new and improved vision. There doesn’t appear to be a Doc Gooden, Ron Darling, Walt Terrell or Sid Fernandez warming up in the wings. There could be the kind of unnoticed or underappreciated gem glistening out of common view right now, the way the talents of Reed and Alfonzo revealed themselves to Valentine before the rest of us could get a good look, but that may require too much blind faith for even those who Gotta Believe to count on. Ultimately, searching for solace in 26- and 13-year-old aberrational examples isn’t the most encouraging way to usher in February, but those seasons did happen. Could they happen again real soon?

Probably not, but we don’t know, do we? I imagine we’ll be able to identify some semblance of success if we happen to stumble upon it.