Anyone who knows Dan Quayle knows that, given a choice between golf and sex, he’ll choose golf every time.

—Marilyn Quayle

The Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue arrives in my mailbox every February to no particular anticipation or fanfare. Certainly its contents are well put together, and I wouldn’t argue they don’t merit an objective hubba-hubba! and a few wolf whistles from those given over to such expressions of approval. Yet I find the Swimsuit Issue disappointing these days because it’s a copy of Sports Illustrated that ain’t got no sports in it.

I’m not kidding. I like sports. I like other things, too, but I don’t like my sports magazines to be scantily clad when it comes to what they usually cover.

Newsstand and ad sales indicate, however, that the Swimsuit Issue is greeted with what might be called broad-based enthusiasm by its reading public, no matter how little there is to read beyond the captions of where the swimsuit models are being languid and who manufactured what little they’re wearing. Indeed, SI hit upon a goldmine when it figured out swimsuit modeling, particularly in the dead of winter and after the Super Bowl, makes for excellent Illustrated, lack of Sports notwithstanding.

Whichever way you wish to classify it, they do a nice job of displaying the merchandise (the swimsuits, I mean). Even if it’s a Brooklyn Decker on the front instead of a Brooklyn Dodger — which had to disappoint Fred Wilpon when he took a second glance at the cover lines — one has to appreciate the photography, the fashion, the artistry…the whatever you like to appreciate.

Even if it ain’t got no sports. Which is what I like in my sports magazines.

Still, I’ve maintained one particularly pleasant memory of a Swimsuit Issue from years gone by. OK, I have a few — I’m not completely made of cork, rubber, wool and stitched white cowhide, y’know — but one edition above the rest stands out: February 9, 1987. Elle MacPherson was on the cover, taking “a dip in the Dominican Republic,” which was as fine as it was dandy, but that’s not the memorable part. It was a two-page spread, shot in the same Caribbean country, described as such:

Kathy and Monika, who waits to bat, are a hit with the Cedeño team, in uniforms by H20 ($72).

I don’t mind telling you that this was a pretty hot picture. Kathy is Kathy Ireland, who was to supermodeling back then what Doc Gooden was to pitching, and you know what she’s wearing besides that “uniform”?

Same thing Doc wore when he was on the cover of SI: a Mets cap.

Now who’s saying Hubba-Hubba?

What made this tableau particularly attractive was the reason Kathy was topped off so stylishly. In the winter of 1987, if you’re posing a model in a baseball motif, you know the ensemble is not complete without royal blue millinery accented by a splash of orange. Baseball, in the winter of 1987, following the fall of 1986, equals Mets.

World Champion New York Mets, if you want to be a model of accuracy.

You’ve got a supermodel? You can’t have her modeling the colors of anything less than a super team. No team loomed as more super or superb at that moment in time than the Mets. It would have been a fashion faux pas to have her in anything less (not that Miss Ireland could have been wearing much less).

Monika, incidentally, is Monika Schnarre; she’s waiting her turn in a Red Sox cap — a perfect pecking order in the wake of ’86.

Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap? With defending champion Pitchers & Catchers barely two weeks away? Suddenly the dead of winter was indisputably springing to life in early February of 1987.

Yes, this is clearly the best illustration in the history of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issues, which, back then, weren’t standalones. They had some actual sports in the pages that came after the modeling, which is significant for our purposes as Mets fans because of the sentence that followed the plug for Kathy’s and Monika’s swimsuit designer.

Turn the page for more on the Dominican Republic’s favorite sport.

At si.com/vault, you can actually virtually turn the page of any Sports Illustrated issue, so I took the advice from the spread of pages 150-151 and did what the magazine suggested 23 years ago. And I came upon a story I vaguely recalled but, for some reason, not as vividly as I recalled Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap.

The article is headlined “Standing Tall at Short,” and is written by Steve Wulf. As long as SI was headed to the Dominican to take advantage of its “lush setting” for shooting models, they decided to explore its other great natural resource: shortstops.

There was a point back in the mid- to late ’80s when it seemed every shortstop under the sun hailed from the Dominican Republic. On April 27, 1986, Wulf wrote, nine different Dominicanos played short in the big leagues. One, Rafael Santana, was doing so for the Mets. Two others, Tony Fernandez of the Blue Jays and Julio Franco of the Indians, would eventually become Mets

“Nosotros somos la Tierra de Mediocampistas,” says Felix Acosta Nunez, the sports editor of Santo Domingo’s Listin Diario. “We are the Land of Shortstops.”

Sadly, the setting for those Dominican youths who grew up to play in the majors wasn’t anything close to lush. From Wulf:

In the Dominican Republic, where the average family income is $1,200 a year, poverty is not an isolated problem; it’s the way of life. Also, the quality of education is very low, lower than in the Caribbean’s other pools of baseball talent, Puerto Rico and Venezuela. So the kids don’t stay in school, not when they can be out on the streets or in the fields playing baseball. “It’s very much like the United States in the ’30s, during the Depression,” says Art Stewart, director of scouting for the Kansas City Royals. “Those were sad times, but they produced great ballplayers because baseball was one of the only avenues of escape.”

Talent plus motivation equaled a plethora of shortstops, particularly the San Pedro de Macoris region, from whence seven 1986 major league shortstops hailed. It was a curiosity, all right, but there was more to the story than the trivia of so many players playing the same position from the same relatively obscure area. The men who made the majors — several of whom Wulf gathered for a shortstop summit — provided baseball equipment and hope for the kids who would come up behind them. Alas, there wasn’t always enough of either. “The players who have made it in the big leagues generously buy gear for the kids, but there is never enough to go around,” Wulf writes. “Too often the youngsters must make do with a glove fashioned from a milk carton, a ball that is a sewed-up sock and a bat made from a guava tree limb.”

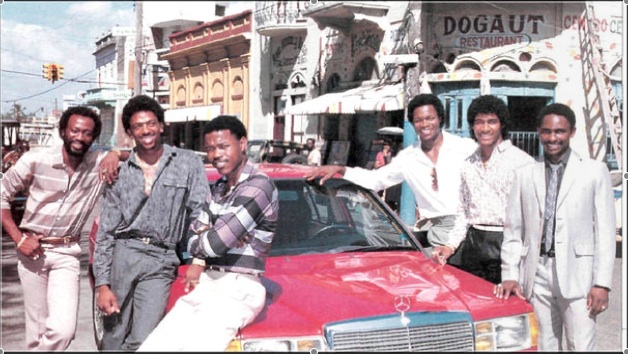

From left to right in the above photo, we meet the cream of the ’86-’87 Dominican shorstop crop: Alfredo Griffin, Julio Franco, Rafael Santana, Tony Fernandez, Mariano Duncan and Jose Uribe. Santana was hardly the star of this Dominican shortstop class; that distinction belonged to Fernandez (whose game mysteriously flickered during his abbreviated 1993 Met tenure). But Ralphie, as his teammates used to call him, shines in the story, nonetheless, quite befitting his status as a World Champion New York Met.

Though he was never considered on the same lofty level with his fellow Dominican shortstops (or ’86 teammates), Wulf describes La Romana native Santana — “the only one with a World Series ring” — glowingly in his piece. He’s the man who “paid [his dues] the longest,” stuck first in the Yankee farm system, then the Cardinals’, where Ozzie Smith left everybody waiting. “Playing in the minors for so long taught me patience,” Santana told Wulf.

You can see the patience in the way he plays shortstop, the way he makes every play close. The Mets finally turned to him in the middle of the ’84 season, and he has been their starter ever since.

Rafael lasted only one more season as a Met. The organization was high on Kevin Elster and traded the incumbent shortstop after 1987. Santana was steady defensively if indifferent offensively. Demographically, though, he was a sign of shortstops to come. According to Ultimate Mets Database, fifteen of the 107 Mets to play shortstop through 2009 were from the Dominican Republic — nearly 14%. Eleven of them were Santana’s successors.

Rafael lasted only one more season as a Met. The organization was high on Kevin Elster and traded the incumbent shortstop after 1987. Santana was steady defensively if indifferent offensively. Demographically, though, he was a sign of shortstops to come. According to Ultimate Mets Database, fifteen of the 107 Mets to play shortstop through 2009 were from the Dominican Republic — nearly 14%. Eleven of them were Santana’s successors.

The most famous and accomplished of them as a Met, at least individually considering he doesn’t yet have a World Series ring, is Villa Gonzalez’s Jose Reyes, hopefully back in the saddle on Opening Day 2010. San Cristobal’s Jose Vizcaino held down the position effectively for a couple of years in the mid-’90s. The rest didn’t necessarily distinguish themselves as Met shortstops.

Chronologically, they were:

• Junior Noboa (1992)

• Tony Fernandez (1993)

• Manny Alexander (1997)

• Wilson Delgado (2004)

• Anderson Hernandez (2005-07, ’09)

• Argenis Reyes (2008-09)

• Fernando Tatis (2009…a pair of emergency cameos)

• Wilson Valdez (2009)

• Angel Berroa (2009)

Before Santana? It had been three years since a Dominican played short for the Mets when Rafael joined the club in ’84. His most direct predecessor was Frank Taveras of Las Matas de Santa Cru. Taveras manned short, not always brilliantly, from ’79 to ’81. Frankie’s stock-in-trade was base-stealing. He set the pre-Mookie single-season record with 42 bags in 1979, despite playing the first two weeks of that year with the Pirates (who — perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not — went on to win the World Series without him). Before Taveras, the most recent Dominican shortstop on the Mets was Barahona-born utilityman deluxe Teddy Martinez, who played six positions in five Met seasons. As the Super Joe McEwing of his day, Ted filled in often at short during Buddy Harrelson’s various injuries in 1973’s pennant campaign.

Prior to Martinez’s 1970-74 stint, there was only one Dominican who played shortstop for the Mets. In fact, he was the first Dominican Met — and the first Dominican shortstop in the majors. I would not have known about him had I not been staring (in disappointment that it ain’t got no sports, I swear) at Brooklyn Decker’s Sports Illustrated cover earlier this week. If I hadn’t seen Brooklyn, I wouldn’t have thought to look for Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap. If I hadn’t tracked Kathy’s picture down, I wouldn’t have revisited Steve Wulf’s profile of Rafael Santana and his contemporaries. And if Wulf hadn’t drawn me in to his tale of San Pedro de Macoris, I wouldn’t have suddenly become aware of the contribution of Amado “Sammy” Samuel to baseball history.

Amazingly, even in the baseball-mad precincts of San Pedro de Macoris in 1987, Samuel was a bit of a prophet without honor. The locals, Wulf reported, thought outfielder Rico Carty was the first Macorista to make the major. Not so — Sammy got to the Braves ahead of him in 1962. Even Wulf concedes his discovery of “the very first Dominican shortstop to reach the big leagues” could be considered underwhelming.

It’s not hard to overlook Amado Samuel. He played in only 144 major league games over three seasons for the Braves and New York Mets, batting .215 with three home runs and not one stolen base. About the only time his name comes up is when some publication lists the 78 men who have played third base for the Mets. Even the Dominican aficionados have lost track of him; some say he is living in New York City, others say he is in Santo Domingo, still others think he has passed away.

Turns out those folks were wrong. Sammy made Louisville his home from the time he played there in the minors in 1961. He married a Louisville lady, picked up a southern accent and went to work after he was done playing ball at the General Electric plant. “I didn’t play too long after the Mets ’cause I tore up my knee in Buffalo,” Samuel, then 48, told Wulf. “Missed out on the big bucks, I guess, but I’m healthy, doing fine, no complaints.” Not only no complaints, but some justifiable pride:

“Now that you ask, I am proud of being the majors’ first Dominican shortstop. I guess there are a lot of them now. You know, one reason there might be so many is the ground they play on. You’ve got to have very good hands to play on those fields.”

About the only thing I knew about Sammy Samuel before Steve Wulf (and Brooklyn Decker, indirectly) got me up to speed was his nickname. I only knew that because my friend Joe Dubin sent me a recording of the first radio broadcast in Shea Stadium history, and Bob Murphy referred to the Mets’ starting shortstop that momentous day as Sammy, not Amado. Murph, Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson were preoccupied by the wonders of freshly opened Shea to spend a lot of time relating Sammy’s story to their audience on April 17, 1964. Ralph, however, had the privilege of calling the first multiple-run, extra-base hit in Shea Stadium history in the fourth inning this way:

“And SAMUEL has put the Mets out in front! Sammy Samuel with a sharp line drive right over the bag that hit in fair territory, right down the left field line.”

Sammy, who wound up on second, drove in Jesse Gonder and Frank Thomas (despite Thomas falling down en route to home). It put the Mets up 3-1 on Bob Friend and the Bucs. It wouldn’t get any better for the Mets that day. They’d lose 4-3 to Pittsburgh.

It wouldn’t get much better for Samuel as Met, either. Despite the two ribbies and a batting average of .364 after three games, Casey Stengel sent Ed Kranepool up to pinch-hit for him in the eighth. Sammy was never quite the same after that. The first shortstop Shea ever saw watched his offense plummet. Within a few weeks of Shea’s opener, Samuel’s average was down below .200. On a team that wasn’t going anyplace but tenth, Sammy’s spot was soon enough on the bench. Eventually, right after Shea hosted its only All-Star Game, it was Buffalo, then (as now) the Mets’ Triple-A affiliate. He never made it back to Flushing.

Amado Samuel was in on some Met history besides his Opening Day onslaught. He came on for defense, replacing Roy McMillan, after the Mets opened a 13-1 lead on the Cubs at Wrigley on May 26, a game that we would hold on to win 19-1. From it was born the legend of the phone call to the newspaper sports desk:

“How’d the Mets do today?”

“They scored 19 runs.”

“Did they win?”

It was 1964. It wasn’t out of line to ask the followup.

Sammy went 0-for-1 in Chicago that day. His next appearance, May 31 at Shea, would net him two hits and a hit-by-pitch, which sounds like a splendid day’s work…except he had seven at-bats…and the game went 23 innings…and the Mets lost 8-6 in the second game of a doubleheader to the Giants…with Sammy flying to right to end it…after losing the first game 5-3. Sammy played second base from the third (Casey had pinch-hit for starter Rod Kanehl in an effort to score early) through the 23rd.

Starting at third base in the opener of another Sunday Shea doubleheader three weeks later, against Philadelphia, Samuel lined out (the New York Times reported Phillie shortstop and future Met coach Cookie Rojas had to jump “about two or three feet” to make the catch) and popped up in two at-bats. He was pinch-hit for by George Altman in the bottom of the ninth. Altman didn’t do any better, striking out. Then John Stephenson struck out. Every Met who batted made out. That was June 21, Jim Bunning’s perfect game. It kind of took the edge off Samuel’s June 20. As Centerfield Maz noted recently, Sammy collected three hits the day before Bunning cooled him off.

For a guy who played in only 53 Mets games total, Amado Samuel was a part of more weirdness than most men experience in a lifetime. Upon coming across his name in Wulf’s 23-year-old Sports Illustrated article, I wondered if there was more Sammy’s Met tenure than Gumplike accidental tourism. So I asked Joe Dubin what he remembered about Samuel. Joe’s been watching the Mets since there were Mets and he seems to have seen everything that I missed.

“I remember having high expectations for him as a Met,” Joe kindly told me. “But for me, that feeling applied to every new player we got. I immediately envisioned Sammy as a potential superstar as I did every other player we obtained. When I was a kid growing up as a New Breeder, everything was seen through rose-colored glasses.”

That’s funny, I thought. I viewed Teddy Martinez the same way. And Frank Taveras. And Rafael Santana. And Jose Vizcaino. And Jose Reyes. Wilson Valdez…not so much. But there’s still time.

I appreciated Joe’s recollection, but still I wondered. I flipped through Bill Ryczek’s essential early-Mets history and learned only that Amado Samuel was, come 1965, part of “probably the sorriest Triple A club in baseball”. For the record, the ’65 Bisons, chock full of discarded ’62-’64 Mets, went 51-96, placed eighth of eight and finished a distant 34½ games out of first. They were even worse than the notoriously bad Bisons of 2009 (a league-worst 56-87 despite being stocked with so many past and future Mets).

The only 1964 Mets yearbook I have is a revised edition, an edition out of which Sammy Samuel was revised right out of once he was demoted to Buffalo. The only 1964 program I have offers no biographical information either, but the scorecard portion offers a happy recap. Thanks to whoever filled it on May 13, I can tell the Mets beat the Milwaukee Braves 5-2, that Jack Fisher beat Tony Cloninger and that Samuel, wore 7, batted eighth, flied out to right, grounded to short, grounded to the pitcher and grounded to third (5, unassisted). I also learned from an advertisement accompanying the scorecard portion of the program that for a Grouchy Stomach or a Nervous Tension Headache, I should take Bromo Seltzer. I suppose with the Mets in the midst of a 53-109 season, the Bromo Seltzer people figured Mets fans were a prime target audience for their product.

Still, nothing much on Samuel. I checked next with Jason. I asked him to pluck Sammy’s 1964 card from The Holy Books and let me know what it said on the back. After declaring it “Strangest. Request. Ever.” he dutifully reported that Topps dutifully reported, “The Mets acquired Amado from the Braves in late ’63. The youngster jumped from Class D to Triple A before coming to the majors in ’62.”

There was also a trivia question regarding the holder of the Giants’ record for hits in one year. Then as now, the answer is Bill Terry.

Before getting completely off track, I discovered the SABR Biography Project had not long ago profiled one Amado Samuel, a.k.a. our Sammy. According to Malcolm Allen’s comprehensive research, major league shortstops have continued to come out of the Dominican Republican at a rapid rate in the two-plus decades since Steve Wulf visited San Pedro de Macoris. By 2007, more than a hundred had taken a turn at the position. And during the games of September 24, 2005, Allen writes, fourteen different Dominicans trotted out to short (including Reyes and his opposite number that night, Cristian Guzman of the Nationals). The author confirmed what Wulf asserted in 1987, that Samuel was indeed the “first Dominican major leaguer to primarily play shortstop, as well as the first big leaguer from San Pedro”.

Allen does a magnificent job of following Samuel’s entire life — which, at age 71 is still going strong in Louisville — including his sale by the Mets back to the Braves after the ’65 season. Samuel needed to be moved out of the organization to make room for a younger shortstop…a fellow by the name of Bud Harrelson.

Thus, in a way, Sammy Samuel is connected to both World Champion New York Met shortstops. His departure created space for Buddy and, regarding his countryman Ralphie, he told Wulf in 1987, “I’ll go to a game in Cincinnati once in a while…but the Mets are still my team. I like the shortstop with the Mets, Santana. He’s pretty good.”

Twenty-three years ago, a retired baseball player who most everybody had forgotten about — and who hadn’t been a Met for twenty-three years to that point — pledged allegiance to the team that let him go and offered an elegant benediction to the unassuming player who followed twice in his footsteps: as a Dominican major league shortstop and as a New York Met shortstop. So it turns out Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap wasn’t the most beautiful thing Sports Illustrated featured in that Swimsuit Issue after all.

Thanks to the blog Condition Poor for unwittingly lending us the image of the 1964 Topps Amado Samuel card.

Please join Frank Messina and me on Tuesday, February 16, 6:00 PM, at the Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village for a night of Mets Poetry & Prose. Details here, directions here.

Hi Greg,

Regarding his baseball card, Amado was assigned number 129 and was part of the first series released for the year (my collection pales compared to Jason’s but I do have his card). You’ll also note he is in a Braves uniform but without a hat or logo on the jersey to identify him as anything other than a Met.

The same does not hold true for Charlie Smith, who kicked him off third after being obtained from the White Sox two weeks into the season. The eventual Met home run leader with 20,Topps touted Smitty as a Met but didn’t bother to alter the White Sox cap and jersey he wore (the Mets did brush-strok his cap and replaced the Sox logo with an obviously too large NY for his yearbook photo).

So Topps exhibited more respect for the major’s first Dominican born shortstop than they did for one who was partially responsible for his eventual demotion. A small tribute, but a tribute nonetheless.

How I long for the days when pop-culture figures wore Met gear not with irony, but to identify with the best, most badass team in baseball. The Met logo was synonymous with excellence, and with a fair amount of cachet that was exclusive to these precincts.

What is wrong with Dan Quayle? He’s crazy. Marilyn was hot for a lawyer.

Kathy Ireland will always be a hottie. Think she could play 2B for us?

Personally, I used to like it when the swimsuit issue day was the week after the Super Bowl (Tuesday) and it was a regular issue with sports in it. I have every swimsuit issue since 1977. I remember that Kathy Ireland picture…now I just have to sneak to the basement and find the issue….

I like to read the sports inside too, but you can’t argue with what sells Greg.

I would have to rate Cheryl Tiegs’ (sp?) infamous 1978 (’77?) fishnet-suit shot as a cut above Our Kathy. But Ms. Ireland is a solid #2.

[…] amid an eclectic roster that included Choo Choo Coleman, first black Boston Red Sock Pumpsie Green, first Dominican major league shortstop Amado Samuel and champion Mets to be Cleon Jones and Bud Harrelson. In retirement, Sammy Drake […]