Say — or should I say hey — you know who was a really good baseball player? Willie Mays.

You probably knew that already, but you’ll really know it if you read Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend by James Hirsch. You’ll know a ton by the time you float through its 560 pages of text. You will, I’m certain, feel what Brad Hamilton meant in the “no shirt, no shoes, no dice” scene from Fast Times At Ridgemont High when he instructed Spicoli and his stoner buds, “Learn it. Know it. Live it.” Even if you’re fairly familiar with the Willie Mays story (as I was going into this book), you’ll likely be astonished by at least three iotas of information per chapter, stuff that transcends his 660 home runs, his 1,903 runs batted in, his 3,283 hits, his 2,062 runs, his two MVP awards, his 12 Gold Gloves and his 24 All-Star selections.

Willie Mays was the last of the big-time barnstormers.

Willie Mays positioned his teammates from center field.

Willie Mays tended to a bloodied John Roseboro after his own pitcher, Juan Marichal, took a bat to his head, thereby defusing one of modern baseball’s ugliest confrontations.

Willie Mays received multiple standing ovations from the Ebbets Field crowd in his last game before reporting to the army despite being the enemy.

Willie Mays cleared the basepaths for trail runners like he was a fullback, deking relay men and bowling over catchers in the process while the guy behind him inevitably moved up 90 feet.

Willie Mays’s respective last at-bats in the 1962 regulation season, pennant playoff and World Series produced crucial hits each time he swung.

Willie Mays played in 150 or more games in more consecutive seasons than anyone, including Cal Ripken.

Willie Mays gave a kid in San Francisco a ride to the ballpark simply because the kid rang his doorbell.

Willie Mays said “hey” a lot but never said “say hey,” except on a record.

America could hardly get enough of Willie Mays for 22 seasons. I couldn’t get enough of Willie Mays for 560 pages, though Hirsch gave me a lot. If Willie Mays is not the most incisive of personality studies, it is an absolute first-rate biography of a baseball career set against the backdrop of a couple of baseball and generational eras. It is highly recommended to any baseball fan who thinks being absorbed deep within one of the game’s golden legends constitutes the most delightful road trip possible.

Still, I’d like to get more Willie Mays, and I know where I’d like to get it. I’d like a generous helping at Citi Field, home of the last team for which Willie Mays played, situated in the city Willie Mays made his own when he first rounded first and took off for immortality. If Hirsch’s book makes anything implicitly clear, it’s that New York’s National League ballpark must commemorate the career of New York’s greatest National League ballplayer.

That’s not Hirsch’s stated agenda, but it is mine.

Citi Field is much improved in the history department in 2010. To that I say wonderful. The banners, the bricks, the museum…it’s as if they’ve opened Mets Stadium after a year spent killing time at a neutral site. Sincere applause from this heretofore critical corner for those efforts.

But more can always be done, and I’d like to start with something for Willie Mays at Citi Field. It’s not so much that Willie Mays deserves it. It’s that we deserve it.

“New York was home,” Hirsch writes of Mays’ attitude when word broke that Horace Stoneham was planning on moving the Giants to San Francisco. “Everything was familiar; the fans loved him. He didn’t particularly want to say good-bye to New York, and New York certainly didn’t ant to say good-bye to him.”

Willie Mays is our legacy. San Francisco — which was reluctant to accept an East Coast import as its own — celebrates him in retirement, but it was New York that embraced him from the moment he appeared on the horizon in 1951 and it was New York that welcomed him back when a historic wrong was righted in 1972. The feeling was mutual. Mays, upon his trade to the Mets:

“This is like coming back to paradise.”

It wasn’t overstatement given the depth of feeling Willie generated as a Giant between ’51 and ’57 and maintained as a visitor from ’62 onward. It wasn’t out of the norm when the St. Francis Monastery of Manhattan’s recorded telephone message — “Your Good Word for Today” was “New York has reason to rejoice these days. Willie Mays has returned. There is some heart in professional sports.”

The heart wanted what the heart wanted, particularly Joan Payson’s heart. Mrs. Payson made Mays II happen. She was the minority Giants stakeholder who voted (through her bag man, M. Donald Grant) to keep the team, like its centerfielder, where it belonged, in New York. She was the Met owner who was happy to fund a new franchise in part because it meant Willie Mays would come around nine times a year. She tried to buy the Giants from Horace Stoneham. She tried to buy Willie Mays from Horace Stoneham. On May 11, 1972, she succeeded.

And on May 14, 1972, it paid dividends when Willie Mays adjusted headgear adorned with an NY for the first time since September 29, 1957 and hit what turned out to be a game-winning home run. He did it, strictly speaking, for New York, as in for the New York Mets. But he also did it, not so metaphorically, for New York as well.

We, as in New York, loved Willie Mays all along. The Giants fans of the early ’50s recognized immediately they’d been granted a gift from the gods when he came up from Minneapolis. The Dodger fans throughout the ’50s cheered his genius for the game they loved even if he played of the team they hated. In July 1961, nine months before the Mets existed, Yankee Stadium hosted an exhibition between the Yankees and the San Francisco Giants. The game didn’t count except in the hearts of “Giant-starved New Yorkers,” as Charles Einstein put it. More than 47,000 parishioners showed up, and “they rocked and tottered and shouted and stamped and sang. It was joy and love and welcome, and you never heard a cascade of sound quite like it.”

“New York,” Mays said later, “hadn’t forgotten me.”

New York would take every opportunity to remember Willie Mays when he began returning regularly in 1962 — “The center field turf at the Polo Grounds looks normal this weekend for the first time in almost five years,” wrote Arthur Daley in the Times upon San Francisco’s first trip in. Old Giants fans, old Dodgers fans and new Mets fans all embraced him. The Mets held a night for him in the Polo Grounds on May 3, 1963, when Bill Shea publicly asked, before an appreciative crowd, “We want to know, Mr. Stoneham, Horace Stoneham, president of the Giants — when are you going to give us back our Willie Mays?”

The answer was nine years later. Willie Mays’ homecoming was as storybook as it could get, No. 24 for the Mets homering against the Giants at Shea to win on Mother’s Day 1972. No mother was any happier than the big mama of the Mets, Joan Payson. It had been a decadelong quest of her to put Mays into A-Mays-in’. When the Mets were forming, Payson still owned 9 percent of the Giants, valued at $680,000, and she had to sell it. According to Hirsch, she offered it to Stoneham free and clear of financial compensation. All he had to give her, for her new ballclub, was his center fielder.

Willie Mays for 9 percent of the Giants…it would have been a steal for Payson, but Stoneham didn’t go for it. It took until ’72 to make the dream a reality. Of course Willie wasn’t the Willie he was in ’62 by then (which is why all it took was pitcher Charlie Williams and a reported sum in excess of $100,000, though Stoneham claimed he never took any of Payson’s money; he just wanted Willie to be “taken care of”). His superstar emeritus status, however, hadn’t diminished one bit, which is why Willie Mays becoming a New York Met was and remains one of the most mindblowing midseason trades in Mets history.

He played well, too. He was 41 years old yet helped the Mets reel off eleven consecutive wins that May, putting New York six games ahead of the field in the N.L. East. Murray Kempton described a sequence of events from May 18 in which Mays, having walked, confused Expo fielders into a flurry of bad throws that resulted in two runs, each “the unique possession of Willie Mays, who had hit nothing except one tipped foul.”

Eventually injuries took their toll on the roster and age slowed down an overworked Willie, yet Mays was no charity case in ’72. No Met put up a better on-base percentage and he was second on the club in batting average and slugging percentage. Plus he was Willie Mays. Wrote Jeff Greenfield at year’s end, “Willie Mays is reminding New York of our own best moments, and our own best hopes.”

The trade of Williams for Mays was no mere agate type transaction and this was no mere spare first baseman/outfielder. Willie Mays as a New York Met was, in every sense of the word, a big deal.

Hirsch explores 1973 as well as 1972, which was the proverbial double-edged sword of Mays’ Met tenure. On one hand, Mays could be prickly (to put it mildly) at this advanced stage of his career and a handful for Yogi Berra, who didn’t particularly crave having him around at the owner’s behest. Willie hit .211, which reads like blasphemy. On the other hand, he was Willie Mays, he knew more about baseball than anybody around, and he shared with grateful teammates. Tom Seaver told Hirsch Mays conferred with him on where he wanted him playing depending on who was batting and how he’d be pitching to him — and that no other position player ever did that.

Willie Mays’ final Met season might have gone down as a footnote to his 1972 return, except the 1973 Mets were destined to live on in memory. The Mets gave him a night at Shea, September 25 in honor of his impending retirement. A sellout crowd developed something in its eye for a very long time, no more so than when Willie gave his valedictory:

I see these kids over here, and I see how these kids are fighting for themselves, and to me it says one thing: Willie, say good-bye to America.

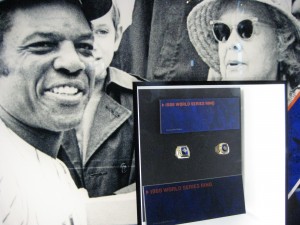

With that, Shea erupted and the Mets fought for their pennant. They got the divisional half of it within the week. With Willie taking a very mighty swing in Game Five of the NLCS against the Reds, delivering a key run and scoring another, they secured the rest. Proper editing would make that the last scene of Willie Mays’ career, but the World Series he played a role in securing would result in some pretty gory bonus footage. He played center, the sun field, in Oakland and he was no kid, Say Hey or otherwise, out there. Mays fell down, balls fell in and a simpleminded summation was born. Whenever a great athlete started showing his age, it became easy enough to write him off with, “What a shame it is when a star hangs on too long. Look at Willie Mays in the 1973 World Series.”

Yes, look at Willie Mays in the 1973 World Series. Look at who drove in the eventual go-ahead run in Game Two: Willie Mays. Look at who capped off a 22-year career the way he began it, as the center fielder for a miraculous New York National League pennant winner. Look at an all-time great who gave millions the thrill of being on their team even if he was at the end of the line.

Mays and the Mets were supposed to ride off into the sunset together after 1973. Willie maintained a coaching position in retirement, but his responsibilities were ill-defined and once Mrs. Payson was out of the picture, good old M. Donald Grant began spitefully insisting tabs be kept on Willie’s comings and goings. Mays outlasted Grant, however, and when Willie was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1979, he was supported by a Met contingent in Cooperstown.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, as was his habit throughout the ’70s, stepped in to ruin things. Willie had taken a rather ceremonial job with Bally’s of Atlantic City, mainly playing golf with high rollers. Kuhn ordered Mays to quit at once or lose his coaching job. Willie needed the Bally’s gig, so he stepped away from baseball. Nevertheless, the new Doubleday-led ownership group continued to have Willie back for Old Timers Days in the early ’80s, and Mays was always introduced last at Shea, always garnering the biggest hand.

Then, as was the case in 1957, he disappeared to the West Coast. The San Francisco Giants got around to retiring his number in 1983 and brought him back into their fold once Bowie Kuhn’s successor, Peter Ueberroth, lifted the nonsensical ban on Mays (and Mickey Mantle). Peter Magowan, who saved the Giants for San Francisco when they were nearly moved to St. Petersburg, gave Willie Mays a lifetime contract to serve as Willie Mays…as if there could be a higher calling.

The Mets-Mays connection has been understated over the past 25 years. He has returned to where he finished up twice that I can recall, in July 2000 when the Mets commemorated their 10 Greatest Moments (Willie was given a discrete introduction as part of the ’73 Mets) and when they Shea’d Goodbye in 2008. Willie, in a Mets batting practice cap, came out third-from-last, just after Darryl and Doc, just before Mike and Tom. He was received enthusiastically both times. In St. Lucie, there are three thoroughfares named for Met legends: Tom Seaver Curve, Gil Hodges Road and Willie Mays Drive. In Mets Plaza, if you come down the back stairs from the 7 train, the first two player banners on the first lamp post you encounter portray Bobby Ojeda and Willie Mays. In the montage of images that fill the Mets Hall of Fame, there’s one very nice one of Willie Mays chatting with Joan Payson. His 1973 Topps card has been spotted on the Field Level alongside Jerry Koosman’s, Bud Harrelson’s and those of other beloved Mets.

And of course No. 24 almost never makes it out of mothballs. Kelvin Torve famously wore it for a few minutes in 1990 until an outcry ensued and Rickey Henderson, not too shabby a player himself, donned it as a player and coach.

I’m not going to advocate here for the retirement of Willie Mays’s number by the Mets. Oh, I think it should have happened years ago, and that if Lindsey Nelson had announced on Willie Mays Night in 1973 that no Met would ever wear it again, New York would have nodded and roared. But given how emotional the issue of number retirement is, particularly among this notoriously insecure fanbase (What about Mike? What about Keith? We can’t multitask!), I don’t see it happening. The vague non-retirement retirement of Willie Mays’ number carries its own cachet at this point anyway.

I am, however, here to advocate for something to be done to honor Willie Mays at Citi Field. A real honor, not just an incidental “he played here, too” type of thing. There’s no shame in sharing a lamp post with Bobby Ojeda, but the Willie Mays who electrified New York in the 1950s, glowed on every occasion here in the 1960s and absolutely lit up the Metropolis’s face in the 1970s deserves something more.

Bobby gets to spend lots of time with Willie. Give us a day when we can hang out with the Say Hey Kid.

We who love and appreciate the breadth and depth of New York National League baseball deserve something more.

I have a few ideas.

The Say Hey Concourse. Center field was Willie’s address at the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium. Let’s rename the area behind center at Citi for the man who defined it. All you need is a sign, a few pictures from ’51 to ’57 and ’72 to ’73 and you’d have a marvelous bracket to complement the Jackie Robinson Rotunda. The great Dodger at one entrance, the great Giant/Met at another. The tradition of New York National League baseball spoken loud clear from front to back. Talk about strength up the middle. And if you’ve ever stood out there and tried to have a conversation while music is blasting and burgers are cooking, you know you pretty much have to say “HEY!” to have any kind of conversation.

The Catch Installation. As you can read in detail here, artist Thom Ross created an incredible five-piece monument to one of the greatest catches in New York postseason history (right up there with Endy in left and Rocky in right) and it needs a permanent home. What better place than where National League baseball continues to be played in New York? Given the dimensions of the Citi Field outfield, what better statement to make than honoring on our premises The Catch Willie Mays made in a park — the one where the Mets were born — a mere Triborough Bridge away? The San Francisco Giants are having a Catch bobblehead day this year. Let’s do them four better and show that The Catch was no kitsch.

(And while we’re at it, let’s restore the Tommie Agee home run marker high above left field. Like Mays’ 1954 run, catch and throw off Vic Wertz, the only fair shot to the Upper Deck at Shea deserves to live on even if its environs were torn down.)

Willie Mays Day. The Mets gave him a night in the Polo Grounds. The Mets gave him a night at Shea Stadium. Let’s complete the trifecta. Let’s have a day for him next month, the afternoon of May 9, three days after Willie Mays turns 79. Why then? It’s the Giants at Mets, and it’s Mother’s Day. What an opportunity to recall both Mays and Mrs. Payson. There’s no other promotion scheduled, so let’s do it. Let’s reach out ASAP to the Mays camp. Make a contribution to the Say Hey Foundation, Willie’s cause for kids. Promote the book (an authorized biography) on the scoreboard that weekend. Make this happen. The Mets have really elevated their historical game in Citi Field’s second season. Take it higher. Bring in the greatest ballplayer most people who saw Willie Mays will swear they ever saw.

In 1999, the Mets held a night for Hank Aaron, who played against the Mets. They held a night for Ted Williams, who retired before the Mets ever played. There was no good reason for either but they were both lovely gestures in the spirit of love for baseball. Ralph Kiner got a night three years ago for no other specific occasion than it was an excellent idea to pay tribute to Ralph Kiner. The timing of Willie Mays Day to coincide with Mother’s Day and the Giants coming is helpful, as is the release of the book, but there’s no reason needed to do this beyond he’s Willie Mays, he defined New York baseball and he was and is one of ours.

Willie Mays said “hey” to this city nearly sixty years ago and to this franchise almost forty years ago. Let’s say it back one more time.

Great ideas, particularly the “Say Hey Concourse”. I am 100% behind that. It’d be great to have a retired-style #24 displayed at the concourse entrances as well. Why not have fun with that whole thing?

Greg, you’ve already heard my suggestions, but in case anyone else is reading: fill up all that empty space in the bullpen gate with orange/blue specks and some neon men, as it’d segue nicely on your walk up to Shea Bridge. Change the Verizon Studio to “Verizon presents Kiner’s Korner” (I’ll meet the front office half way on that one). Jace’s idea of a wall listing the names of every Mets player in history is solid (call it “Meet the Mets!”). And it’s been said plenty of times elsewhere: more pictures along the walls, more player associations with food stands (Rusty to Blue Smoke, Mex to Taqueria, etc).

I’m quite happy with the upgrades from last year, and I’m happy the Mets have said it’s not stopping there. Honoring Mays is a great way to continue.

These potential enhancements (which are excellent) demand a post of their own, but I’d throw in two more: Caesars Presents the 41 Club; and Acela Presents the Stork Club. New York, right?

It’s so nice to be coming at this from a position of “here are ways to embellish the great things they’ve done” as opposed to “why is there nothing?”

Love the idea of balancing the emphasis on Jackie, with a salute to Willie – having “THE CATCH” in the rotunda would definitely do that.

I’m just old enough to remember Willie’s playing days, and by that I don’t just mean the aging hero who returned in ’73, but rather the days when he was still playing (exceedingly) well for the Giants. You always feared the two Willies (McCovey, of course) in their line up. And, watching him patrol the outfield was, simply put, poetry.

Yankees fans may argue, but, to me Willie was clearly a better centerfielder than The Mick.

So, I’d vote to “Say Hey” to all three of your proposed salutes, and if the Mets insist on keeping the silly plastic #42 in the rotunda, adding #24 to it will only make it look better.

I don’t want to call the Say Hey Concourse a counterpoint to the JRR, for there’s no need to go against a fine tribute out front, but I think it would be a great complement, historically and tonally. The SHC would be vibrant and fun whereas the JRR is solemn and hallowed.

Per Kevin’s allusion, one of the pix should definitely be of Willie playing stickball on St. Nicholas Place.

A perfect addition to the Say Hey Concourse: a stickball batting cage.

That is a brilliant touch.

[…] Say Hey, A Heart in New York « Faith and Fear in Flushing […]

All these ideas make too much sense for the Wilpons to even entertain them.

I LOVE this idea! Willie Mays is New York, despite San Francisco’s belated attempt to claim him. Perhaps the Giants visit could also Turn-back-the-clock and Mets wear ’72 home uniforms and the Giants wear ’51 road ones. NY on all caps! Retire #24 (and also somehow honor all NY Giants and Brooklyn Dodger HOF players that played in NYC prior to ’58, perhaps by having a NY or B with their name on it).

Here, here! Hey, hey!!

Say hey! I like the idea of Willie Mays day/night at Citi Field. I’ve said from the beginning that there should be equal parts Giants and Dodgers there. In the rotunda, one side of those big numerals is a blue 42, and on the other side is an orange 24. and maybe have it sideways so that it doesn’t play favorites.

You have the Jackie Robinson Rotunda in the front. The Seaver and Hodges VIP entrances. Willie Mays field behind Centerfield as an idea. And Casey Stengel Plaza behind home plate on the Promenade level is another one.

Now, if we only had a management who cared enough to put a manager and a team on the field that would at the very least play meaningful games….in APRIL, let along September.

[…] Today is New York Met and New York Giant icon Willie Mays’s 79th birthday. If the Mets are marking the occasion during the visit of the Giants this weekend, they are keeping it a well-hidden secret. […]