Duke Snider was hugely talented, agreeably and disagreeably human by turns, and essential to the myth of the Brooklyn Dodgers — for the move west from Ebbets Field to the other side of the continent threw his career into permanent decline, almost as if the Duke of Flatbush had lost his royal powers when he was exiled.

It was a cruel bit of irony that Snider should have been the one undone by replacing a B with an LA on his cap. He was from Los Angeles — straight outta Compton, as it would be put later in a rather different setting — and at first he welcomed the chance to come home. But where Ebbets Field had invited lefty sluggers to bash the ball onto Bedford Avenue, the converted Olympic track-and-field stadium known as Los Angeles Coliseum promised them doom: To Snider’s consternation, it was 440 to right center. Snider had hit 40 or more home runs for five years running in Brooklyn, and was just 31. His first year in L.A., he hit 15. In shockingly short order (helped along by a bad knee), he became a part-time player, then a Met, then a Giant in a bit of unhappy farce, and then retired at 37. (Tip of the cap to our pal Alex Belth for passing along an excellent Dick Young retrospective from Inside Sports about Snider. You can read it at the bottom of this Bronx Banter post [1].)

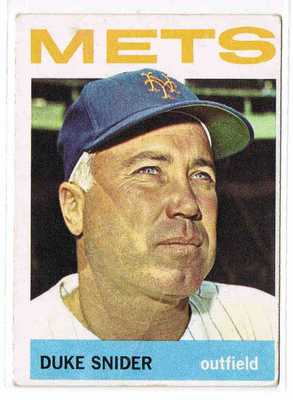

[2]We remember Snider for the memory of him as a Dodger, and for that lone campaign as a Met. His 1964 Mets card captures him perfectly, in oversaturated Topps colors: silver hair, ice-blue eyes, the penetrating gaze and granite chin of a captain of infantry or industry. Yet I’m torn when I think of those old New York players and their victory laps around the Polo Grounds. They bind the Mets more closely to the Dodgers and Giants and Yankees than blue and orange and pinstripes already did, it’s true — and I’ll always be a sucker for mystic chords of memory. But the likes of Hodges and Woodling and Zimmer and Snider and Berra and even Casey himself were brought to New York not because they could help their new club — with the exception of the luckless Roger Craig, they did very little of that — but, as Greg noted earlier [3], to be sideshows meant to distract the paying customers from how shabby the on-field product was. (This self-defeating nostalgia had an encore with Willie Mays’s farewell tour in 1972 and 1973, but I can forgive Mrs. Payson that one: What’s owning a baseball team for, if not trying to stop time for your favorite player?) The Mets got better when they outgrew serving as a rehearsal for Old Timers Day for the Boys of Summer and their ancient adversaries; in paying homage to the 1950s Dodgers and Giants and Yankees who wound up in orange and blue, we should remember that the franchise’s early days would have been less pathetic with fewer such cameos.

[2]We remember Snider for the memory of him as a Dodger, and for that lone campaign as a Met. His 1964 Mets card captures him perfectly, in oversaturated Topps colors: silver hair, ice-blue eyes, the penetrating gaze and granite chin of a captain of infantry or industry. Yet I’m torn when I think of those old New York players and their victory laps around the Polo Grounds. They bind the Mets more closely to the Dodgers and Giants and Yankees than blue and orange and pinstripes already did, it’s true — and I’ll always be a sucker for mystic chords of memory. But the likes of Hodges and Woodling and Zimmer and Snider and Berra and even Casey himself were brought to New York not because they could help their new club — with the exception of the luckless Roger Craig, they did very little of that — but, as Greg noted earlier [3], to be sideshows meant to distract the paying customers from how shabby the on-field product was. (This self-defeating nostalgia had an encore with Willie Mays’s farewell tour in 1972 and 1973, but I can forgive Mrs. Payson that one: What’s owning a baseball team for, if not trying to stop time for your favorite player?) The Mets got better when they outgrew serving as a rehearsal for Old Timers Day for the Boys of Summer and their ancient adversaries; in paying homage to the 1950s Dodgers and Giants and Yankees who wound up in orange and blue, we should remember that the franchise’s early days would have been less pathetic with fewer such cameos.

Young’s retrospective about Snider is itself thick with nostalgia — in it, the Duke and Pee Wee and Oisk ride again, celebrating at Borough Hall and carpooling from Bay Ridge and jawing with sportswriters and fans and opponents and each other. But Young doesn’t shy away from Snider’s gaffes, like telling Roger Kahn he played for money or shouting that Brooklyn’s goddamn fans didn’t deserve a pennant.

Snider caught hell for that last one, at least until he hit his way back into their good graces. Thinking about that, I was drawn to today’s bit of Mets news: Carlos Beltran’s preemptive declaration that he would play right field, sliding over for Angel Pagan. “In my heart, I still feel that I can play center field,” Beltran told reporters, “but at the same time, this is not about Carlos — this is about the team.” You could almost feel the disappointment as the assembled beat writers watched a juicy spring-training storyline disappear with a minimum of fuss and strife; by contrast, Terry Collins’ relief was practically palpable.

Beltran, being Beltran, will get little praise from a certain segment of the fan base for putting the team above his own pride. (Let me guess: His agent put him up to it so he can extract more value from somebody.) I’ve given up trying to convert those who can’t help but see Beltran as embodying all that’s supposedly wrong with baseball today. They dislike one of the franchise’s greatest players for making the game look easy, for not throwing tantrums when he fails, for not trusting his knee to the Mets’ idiot doctors and dithering front-office cheapskates, for having Scott Boras as his agent, for not managing to hit an impossible 12-to-6 curve when geared up for a fastball, for attending a charity meeting about building schools in Puerto Rico instead of going to Walter Reed, for being injured, for being rich, for being Carlos Beltran.

Here’s what I wonder: How would Duke Snider be treated today, in a world in which salaries have grown astronomically, our demand for information is voracious and spastic, and a reflexive cynicism threatens to pervade everything? Snider’s per-year earnings as a ballplayer maxed out at $46,000. That’s about what Carlos Beltran will make in his first 3 2/3 innings of 2011. If they could trade places, would Snider’s sad decline from a knee injury have been blamed on his lack of toughness instead of a Yankee Stadium drain? Would his home-run outage in L.A. have been attributed to a lack of passion rather than a reconfigured park? Would Duke Snider have been a hero if he’d made $46 million instead of $46,000?

Two great preseason publications are out, each with contributions from Faith and Fear and other Mets writers you know and love. Get your hands on Amazin’ Avenue Annual here [4] and Maple Street Press Mets Annual here [5].