In the spring of 1987, Gary Carter’s book A Dream Season hit stores. My mom heard Carter would be at Haslam’s Book Store in central St. Petersburg and drove down there to get me a signed copy, leaving plenty of time to wait in line. Only there was no line — St. Petersburg was still affectionately disparaged as God’s waiting room then, and not even the presence of the All-Star catcher of the World Champions of baseball was enough to draw a crowd to a bookstore in the middle of nowhere on a hot afternoon. There was just Gary Carter, looking somewhat wan and bored.

My mom felt sorry for him, and so she stayed and chatted for a while — about the Mets and their season (she has always been a huge fan), but also about her sometimes wayward son [1] and his writing ambitions and where he might go to college the next fall. As this story unfolded over the phone, I had two reactions:

1. MOMMMM! QUIT IT!

2. Please don’t let this story end with another rich athlete being curt or dismissive to a fan. Not when the athlete is Gary Carter and the fan is my mom. Because that really might break my heart.

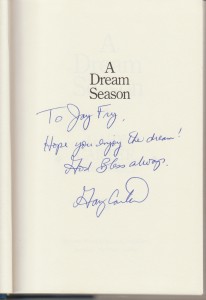

[2]I had, of course, nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met one of her heroes and come away thinking better of him.

[2]I had, of course, nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met one of her heroes and come away thinking better of him.

After I learned that Carter had died — a blow no less painful for the fact that we had all braced for it — I picked up Joshua at school and walked him home in the clammy dark. He vaguely remembers Carter from highlight films, and had him somewhat jumbled up with Mike Piazza, Mookie Wilson and Dwight Gooden. (Which isn’t bad as jumbles go.) I set the record straight and we wound up talking about how it was all too easy to inflate athletes’ successes or failures on the field into judgments of them as people. This is something that started while watching Ken Burns’s Baseball [3], with discussions of how most people were neither heroes nor villains: Ty Cobb said and did unforgivably horrible things to people but was also a pitiable man damaged by a cruel and horrifying childhood, while Barry Bonds was a cheater and a superstar and a jerk and a sad figure all at the same time.

Given such complexities, it was a relief to talk about Gary Carter. It was a relief to tell Joshua that I’d never heard anyone speak ill of him as a teammate, husband, father or friend. It was a relief to say that he was by all accounts something simple to describe and unfortunately easy to mock, probably because it’s so hard to achieve: a good man. Not because of what he’d done behind the plate or at bat, but because of how he’d lived his life and how he’d treated others.

Carter was more complex than that, of course, and he wasn’t perfect: There was a whiff of self-aggrandizement to his relentless enthusiasm, and he was embarrassingly tone-deaf to politics, repeatedly trying to put himself in managerial chairs that were still occupied. But those things didn’t make him a bad person, just human — all of our obituaries, if fairly told, will have buts and to be sures and clauses we’d prefer struck from the record.

It’s been heart-breaking and fascinating to hear Carter’s teammates remember him. For a good chunk of his career, Carter played the toughest position on the diamond while enduring derision from his own teammates, who resented his rapport with the media, ever-present smile and gift of gab — and, one suspects, his unshakeable faith in who he was. They sneeringly called him Teeth, and Camera — even Kid was originally a put-down, one Carter embraced and turned into his own Charlie Hustle.

Those stories from Montreal followed him to New York, where all of his nightcrawling teammates admired him but few seemed to like him. But hearing from them tonight, you could tell the remorse was genuine, and sense that in finding themselves older and grayer and thicker they’d come to think differently of square, uncool Gary Carter from Sunny Hills, California. Keith Hernandez’s grief [4] was so raw that listening to it made you feel like an intruder, but what really got me were the words [5] of a sadder, wiser Darryl Strawberry: “I wish I could have lived my life like Gary Carter.”

Once upon a time, comparing Keith’s Goofus to Gary’s Gallant, I declared myself a Keith person [6]. And I am. But you can declare for the one without diminishing the other. I was always drawn to Keith’s ferocity and brains and his success despite all-too-evident foibles. But that’s not to say I didn’t beam in response to Gary’s buoyant curtain calls, or admire his unflappable stoicism crouching behind the plate in pain and dust, or see his victories over Charlie Kerfeld and Calvin Schiraldi as little parables, lessons that hard work and self-confidence would be rewarded. And as I’ve gotten older and grayer and thicker myself, I’ve come to grasp that the truest measure of who we were will be how others remember us. Living your life like Gary Carter? We should all have such courage of our convictions.

Twenty-five years ago, Gary Carter was kind to my mother. It’s a little thing, but most of our lives are little things, and we determine whether they’re done well or poorly, graciously or indifferently. He wrote God bless always in a book for me. Now I realize he was the blessing.

Greg’s thoughts on Gary are here [7].