We’re into the mid-’90s, and the makeover of The Holy Books … well, it’s dragging a bit.

I’ll sum up the problem with a string of numbers: 45, 22, 19, 20, 17, 35, 8, 9, 10, 8, 13, 13, 9, 17, 9, 14, 16, 14, 13, 15, 13, 12, 15, 12, 10, 13, 4, 14, 20, 13, 24, 20, 19, 25, 19, 24, 26, 20, 22, 17, 29, 21, 29, 24, 28, 22, 27, 26, 21, 22, 23.

That’s the number of Mets to make their debuts each season in club history. To me, the ebb and flow makes for an interesting portrait of how baseball’s changed over time. The Mets of the ’60s used a lot of players — the 45 shouldn’t count, as every ’62 Met was making his debut, but 1967’s 35 new Mets remains the franchise high. But in the ’70s and ’80s the numbers were relatively small. Joshua’s initial interest in the project (and greed for his promised $50) carried him through the ’60s well enough, and in the ’70s and ’80s he was able to reorder each year’s handful of Mets in no time — 1988’s four new Mets (the franchise low) took about six seconds. But starting in the ’90s the annual total rises into the twenties and mostly stays there, and by now the kid’s sick of sorting cards and inserting cards and checking the order of cards, and he’s wondering if $50 was really such a deal.

Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom.

Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom.

Dad: Darrin Jackson had Graves’ disease. I don’t know what that is. No, it probably didn’t make sense to trade for him. Except it let us get rid of Tony Fernandez, who wasn’t any good because he suffered from kidney stones and a lack of interest in being a Met, which should be called Alomar’s disease.

Son: This is really inspiring, Dad! Never mind R.A. Dickey — let’s go get Opening Day tickets!

Sometimes you’re better off saying nothing.

And the cards? We’ve gone from the beautiful Pop-Art cards of the ’60s with their painterly portraits to the goofy explosion of clashing colors that was the late ’70s, through the industrial-looking ’80s, and now we’re in the mid-’90s, when baseball-card design turned crass and high-tech and weird. Cards are gold, and silver, and embossed, and have lenticular layering to produce lame 3-D effects, and are tarted up with little distorted mirror images, and festooned a multitude of other bad ideas. (Kevin Lomon’s ’95 Fleer Update card is the single worst-looking piece of cardboard in The Holy Books.)

We’ll fight through it — the kid perked up a bit at the sight of Edgardo Alfonzo, and soon enough we’ll reach Mike Piazza, and players he actually remembers, and then we’ll be in sight of the finish line.

But as the above indicates, for me the memories have mostly been about baseball cards — and those memories have taken me back to a place that’s not entirely good.

I started buying baseball cards again by accident in the late ’80s, as you can read about here. (Short answer: It was Rickey Henderson’s fault.) At the time my folks lived in St. Petersburg, Fla. It’s a decently lively town now, but this was the late ’80s, when the city still had the rather cruel nickname of “God’s waiting room.”

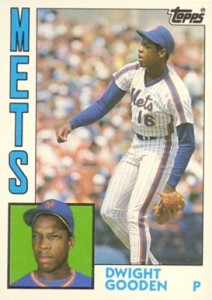

Like every other place then, it was going through the baseball-card boom, and it was my chief hunting grounds. I was working on a long, long list of cards I wanted, and my top two targets were the most expensive Mets rookie cards of relatively recent vintage: the ’83 Darryl Strawberry and the ’84 Dwight Gooden. They were pricey to the point of being unobtainable — I wasn’t even thinking about a ’68 Ryan yet, or a ’67 Seaver, or high numbers, or any of the other things I’d spend too much money and time obtaining later.

I found a Straw with a bit of a wrinkle at a card show in a half-deserted mall that mostly sold prosthetic limbs — a happy defect that took it down to half-price or so. But the Gooden? Oh boy. The Mets had just left for Port St. Lucie, and despite his recent cocaine woes Dwight Gooden was a sure-fire Hall of Famer, a Met and a hometown kid. The Internet was still for physicists, and auctions were conducted by members of the horsey set holding up paddles — if you were in St. Pete and wanted a Gooden rookie, you were going to pay for it.

The central St. Petersburg of a quarter-century ago contained many forlorn, sun-blasted stretches of asphalt occupied by dumpy cinder-block buildings in which indifferent commerce sometimes occurred, and one of those sad buildings was a baseball-card shop run by a guy named Ray and his mostly invisible wife.

Ray was an asshole. He was given to scheming and complaining and was truculent unless he thought he was about to con you out of something, in which case he would feign being friendly for a minute or two before getting distracted and going back to being Ray. In other words, he was like 90% of the people who became baseball-card dealers during the years when price guides were bibles and cards were investments and buyers and sellers alike were mostly unbearable.

Ray hated customers and kids and baseball cards and baseball, and the only thing that changed was the order in which he ranked those hatreds. Meanwhile, I thought I liked Ray. I actually hated him, for all the obvious reasons, but I hadn’t figured this out yet. I thought I liked him because I knew he was teaching me how to tolerate unpleasant people who had something you needed, which I sensed was a valuable skill. That much I was right about.

Anyway, I needed Ray for three reasons:

1. His shop was the closest baseball-card store to my parents’ house at the far southern end of St. Petersburg.

2. His shop was also the best baseball-card store in the area. Ray hated baseball cards, but he had a ton of them — I suspect he’d bought out some other dealer, who’d stuck him with boxes and boxes of unsorted commons from all sorts of years, including hopelessly obscure sets nobody else had and nobody particularly wanted but me.

3. Ray had a 1984 Topps Traded Dwight Gooden.

I would get a little money together and go see Ray, hoping to cross off a few things from my endless want list. If Ray were there, I’d ask him about various sets, which he’d claim he didn’t have because he didn’t want to get up out of his lawn chair behind the counter. Eventually I figured out I could rouse him into vague motion by pretending I needed an obscure card he thought was expensive. If I could get him to pull down three or four boxes of cards in search of things, he’d get pissed off and bark at me to just come behind the counter and look myself, which is what I’d wanted in the first place. I’d put together whatever stack I could afford, then police Ray’s slow-motion checking through the latest price guide, correcting the errors of price and condition that somehow inevitably went in his favor.

And then I’d ask him about that Gooden rookie.

When I’d do this Ray’s eyes would gleam, he’d grin, and then he’d begin to fidget. The card was sharp but miscut, which should have knocked a fair amount off of its value. Ray knew this, or rather Ray would admit this in the face of ruthlessly presented evidence, but he would always respond vaguely that it was no big deal because he knew a guy who could get the card fixed somehow, and in the meantime he wanted to be paid as if it were a perfectly cut Dwight Gooden rookie card. I refused to do this, as did everybody else, and so for a year or two the Gooden rookie sat in one of the carousels atop Ray’s display case, awaiting its visit with Ray’s vague associate and mocking me with its unavailability.

Until one day, for my birthday, I opened up a small package and found … a Gooden rookie. I exulted, hugged my mother, then pulled back and looked at it more closely.

“Tell me,” I said, “that you didn’t buy this from Ray.”

My mom swore she hadn’t, but that miscut was like a fingerprint. She confessed and I hugged her again, a little annoyed that Ray had extracted undeserved money from my mother but mostly grateful that my search was over.

When Joshua and I came to the mid-’80s in the Holy Books makeover, I saw that a few cards I’d selected weren’t particularly attractive choices: Why did I pick Topps ’89 cards of Rick Aguilera and Randy Myers in which they’re staring at the Topps photographer like they’re at the DMV? I knew there were better cards for both, so I took a peek on eBay — and discovered I could get the entire ’88 set, plus the traded cards, for $3. Including shipping.

That was good — and yet it was disappointing to discover the ’88 Mets, those winners of 100 games, had become a collector’s afterthought.

In The Holy Books, Dwight Gooden is represented by his ’92 Topps card, on which he’s called Doc. I’d never liked the formalizing of the nickname — it smacked of rebranding, of hubris, of tempting fate. I decided I could and would do better by Dwight Gooden. But what card would be best for him?

I went back to eBay, wondering … and wondering if I wanted to know.

Ray’s baseball-card store is long gone. I don’t know what’s there now — maybe it’s an artisanal coffee shop where perky baristas are happy to see customers.

I assume Ray is dead, though I wouldn’t be astonished to learn he’s hawking Skylanders figures on eBay from his lawn chair and ripping people off with handling charges.

Dwight Gooden is 48 years old. He retired with 194 wins, and when we hear his name in the news our first instinct is to worry.

And a 1984 Topps Traded Dwight Gooden rookie? Perfectly cut, with four sharp corners, it will cost you $7.50 on eBay. Including shipping.

Wow, that image brought back a flood of memories. Of course, I ordered that set, even as I purchased pack after pack of 1985 Topps (and Donruss and Fleer). And I actually scored 3 Goodens among the dozens of Bill Steins and Joe Altobellis. But every one of those Goodens had a prominent green dot on his nose. This had to be deliberate, right? The most coveted card in the set with a consistent and obvious flaw. I was “lucky” enough to get quite a few Clemens and even one McGwire Olympic card. But those green-dot Goodens… So the miscut on the 1984 Traded Gooden, well, lets just say I’m suspicious. By the mid 1980s, the card boom had started and the company knew that flaws like green dots and miscuts would raise the value of perfect coveted cards, and everything Topps has done since that time with all the fancy processing, layering, and insertion of slivers of bats and jerseys into cards was designed to make its rare products valuable. For the record, all my Altobellis are museum-quality.

Anyone else ever get a green-dot Gooden?

The first time I bought from a dealer who advertised in a national card collector’s magazine in 1982, it turned out one he was just 3 miles from my home at the time. He had minor league sets and Mets team sets, including those from those new companies at the time: Fleer and Donruss. That, and tons of other stuff. I had to get my hands on some.

Upon getting the dealer’s address over the phone, I drove and found he conducted business out of his house on a busy intersection of county roads in northern New Jersey. His screened-in porch was stacked with boxes and cartons of mostly baseball card related goodies…some stacks teetered so high, there was a distinct chance that a tractor trailer rumbling by would have caused a stack or two to collapse on us.

The dealer wasn’t quite like Ray as you describe, Jason, but it might’ve been fitting if I was crushed by a tower or two of stacked cartons of top-loading plastic sheets and factory sets: my epitaph might’ve read, “death by baseball cards”.

This reminded me of an old friend of mine. He was, at the time (early 1980’s), an avid card collector and “investor”. He had this stash of Neil Allen rookie cards that he swore were going to be quite valuable once Neil emerged into one of baseball’s premier relief aces (he was not a Mets fan, BTW). I tried to advise him that was probably NOT going to ever happen but he scoffed at me. I haven’t spoken to him in years but I assume that today he’s really enjoying his binder full of cardboard bookmarks featuring Mr. Allen’s photo.

Jay, I used to visit Ray’s shop back in those days. One day an older lady came in with a shoebox full of cards. He hubby has passed away and she wondered if these old slices of cardboard had any value. He looked through nodding his head and offered the grieving widow $75 for the lot. She seemed delighted and left with a smile. He looked up at me with an evil glint in his eye, holding up a Willie Mays. “This ones worth three times what I paid for the whole box.”