Soon enough, we will concern ourselves with Spring Training hellos, including those from the Mets’ most recent flurry of somewhat tentative acquisitions. There’ll be first-pitch greetings from Shawn Marcum, Scott Atchison and LaTroy Hawkins; first-catch greetings from Landon Powell; greetings for the first time in a little while from previously dispatched Omar Quintanilla; greetings for the first time in a couple of years from Pedro Feliciano (if he has a spare moment when he’s not warming up in anticipation of facing Bryce Harper 19 times this season); and at least one fellow with the initials M.B. waving “HI!” from the outfield — Marlon Byrd definitely, Michael Bourn maybe. The Mets might lack for glamorous, in-their-prime signings, but they won’t be shy of guys introducing themselves to us.

We’ll want all our newcomers to show us something in St. Lucie. Those who do we’ll want to see in Flushing. From there, we’ll want them on the field for seven months, including a generous portion of October.

And if they have to say goodbye after playing a role in turning our milieu into the Promised Land, we’ll understand.

Actually, we’ll qualify that should it become an issue, for we might want to keep our hypothetical world championship team together so it can form a dynasty. But, really, if someone wants to win us a World Series and be on his way to the next phase of his life, it would be rude to throw up any substantial roadblocks.

When the Super Bowl gets underway Sunday night after the completion of its 140-hour pregame show, one of the major storylines will center on Ray Lewis and his attempt to end his career by earning a Super Bowl ring. You may have heard, among other things, that the Ravens’ linebacker will retire when the game is over. If he rides into the sunset in a swirl of confetti (and isn’t caught doing anything illegal en route), he will go out in the best competitive light possible…in the reflected glow of the Vince Lombardi Trophy.

Lewis attempts to do what a handful of all-time greats have done. This was the way for John Elway, Michael Strahan and a few other football notables who won a Super Bowl and then immediately said goodbye. It’s also how David Robinson and Mitch Richmond went out in basketball, a fact I remember only because they won their last games in NBA Finals clinchers against my occasionally beloved Nets (whereas the Nets ended the ABA’s collective career as league champions, though that’s not precisely the same thing).

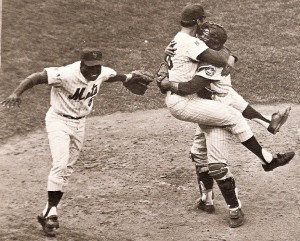

And then there was the sole New York Met whose final game as a professional baseball player wound up with him in the middle of a world championship celebration. That Met was the third man to arrive at the Shea mound as the cameras clicked after the last out was recorded…and he was the first within their ranks to leave the playing field altogether.

Ed Charles certainly waited long enough to become a World Champion. He endured a decade of minor league ball, not because he wasn’t good enough to make it in the majors, but because he chose the wrong time to be young, African-American and in a sport that clung to shameful unofficial quotas regarding how many like him could be on a roster at a given juncture. That’s just surface stuff, of course, for there was nobody “like” Ed Charles: poet laureate of a youthful band of miracle workers and veteran leader among mostly callow kids. Ed was as much the toast of New York on October 16, 1969 as picturemates Jerry Koosman and Jerry Grote, not to mention Tom Seaver, Cleon Jones and everybody else in a Mets uniform. The Glider rushed the Jerrys and embraced the team’s fate as hard and lovingly as anyone could have.

Charles’s final appearance as a big leaguer came under the best possible circumstance. His exit, however, wasn’t planned in the fashion of Lewis’s at this Super Bowl. There was no goodbye tour for the platoon third baseman, no string of press conferences. There was just a perfunctory release a dozen days after he hugged Grote and Koosman. There were some hard feelings between unceremoniously deleted player and bottom-lining front office at the time, yet Charles has been as constant a presence among Mets alumni as any of his brethren in recent decades. He went out on top and he’s remained steadfast among us, proving the best farewells are sometimes the ones that are mere partial finals.

One short rung down on the goodbye ladder, at least in terms of the achievement/aftermath dynamic, are a pair of Mets who played on October 27, 1986, and went out the biggest of winners. Ray Knight hit the difference-making home run that Monday night at Shea and captured the World Series MVP award. Less instrumental in Game Seven was starting left fielder Kevin Mitchell…though he — like Knight, Gary Carter and Mookie Wilson — basically ensured there’d be a Game Seven by executing flawlessly in the tenth inning of Game Six.

Knight and Mitchell finished their Met careers by winning a World Series but then continued to play on elsewhere, allowing them to linger palpably as avatars of what might have been in the Metsopotamian imagination. Neither’s departure was voluntary let alone overly popular. Ray wasn’t offered the money he wanted and signed a lesser deal with Baltimore; World (as in all-world for the plethora of positions he manned) was sent away to San Diego, lest he unduly influence a couple of impressionable young New York Mets. Howard Johnson effectively succeeded Ray Knight at third. Kevin McReynolds, for a while, was an upgrade over Kevin Mitchell. Sentimentally, one can make the argument that each tilted fairly close to irreplaceable.

Only one other Met played his last game as a Met as the Mets were nailing down a postseason series. Remember Chris Woodward? Handy utility type from the middle of the last decade? Woodward saw limited action in the 2006 National League Division Series. His only appearance came when Willie Randolph led him off in the top of the eighth of Game Three as a pinch-hitter for Guillermo Mota, the Mets up on the Dodgers, 7-5. Chris doubled against Brett Tomko, advanced to third on a Jose Reyes flyout and scored when Paul Lo Duca singled. Two innings later, the Mets were NLDS winners in a three-game sweep.

The action was even more limited for Woodward in the NLCS: seven games, nothing doing. Thus, Chris’s last Met appearance came on October 7, 2006, in the cause of a series win…a division series, but still a decent way to make a final impression. The Mets replaced Woodward with David Newhan in 2007 and, probably coincidentally, haven’t been in the postseason since. Woodward bounced about the majors in a utility role until 2011, never again seeing the business end of October. Yet Chris, at 1-for-1, possesses one of only two 1.000 career Met postseason batting averages. The other belongs to Jesse Orosco, who swung away in the eighth inning of Game Seven of the 1986 World Series to drive in the Mets’ eighth run. Orosco would pitch another seventeen seasons but never again record an RBI.

Four other Mets unknowingly said goodbye to us, if not baseball, in postseason wins:

• J.C. Martin’s final contribution to our well-being came at the expense of his wrist, struck by Pete Richert’s toss after J.C.’s bunt in the tenth inning of Game Four of the 1969 World Series. The ball hit Martin as Martin hustled down the line (literally). It bounded away, permitting Rod Gaspar to score the winning run from second. J.C. didn’t play in the fifth game and was traded to the enemy Cubs the following spring.

• Danny Heep pinch-hit for Rafael Santana in the fifth inning of Game Six of the 1986 World Series (before that contest became historic and was merely agonizing). Heep’s double play grounder brought home Knight with the tying run, no small feat given the Mets’ desperation to generate offense versus Roger Clemens in the truly must-win affair. Clemens had been no-hitting the Mets for the first four innings of the sixth game. A productive out was, if not as good as a hit when Heep made it, then critical. That swing completed Heep’s active Met tenure. By 1987, he was a Dodger. By 1988, he was a world champion again.

• Masato Yoshii threw the first three Met innings on October 17, 1999. Octavio Dotel threw the last three that same Sunday. In between, the Mets and Braves played 14½ innings, leaving the Mets down a run, yet saving the best for last in the bottom of the fifteenth: a dozen pitches to Shawon Dunston before he singled; a stolen base; a walk, a sacrifice, a couple more walks; and something with a home run that wasn’t really a home run (even if it kind of really was). While Mets fans soaked in Robin Ventura’s Grand Slam Single in Game Five of the NLCS, keeping the Mets improbably alive for the pennant, they couldn’t have realized they had witnessed the final Met appearances of Yoshii and Dotel, neither of whom were tabbed to pitch in equally epic Game Six (just about everybody else was). Masato was traded to Colorado for Bobby M. Jones three months later and would eventually return to Japan, pitching there through 2007, when he was 42. Octavio went to Houston as partial payment for Mike Hampton in December of 1999 and was, at last check, ageless.

Twenty-one other Mets made their final Met appearances in postseason losses. No sense reliving those incidents, but their ranks include Willie Mays and Jim Beauchamp (1973 World Series); Wally Backman (1988 NLCS); John Olerud, Bobby Bonilla, Orel Hershiser, Dunston and Kenny Rogers (1999 NLCS); Derek Bell (2000 NLDS); Hampton, Bobby J. Jones, Mike Bordick, Matt Franco, Kurt Abbott and Bubba Trammel (2000 World Series); and Steve Trachsel, Darren Oliver, Roberto Hernandez, Chad Bradford, Michael Tucker and Cliff Floyd (2006 NLCS).

Is there a long-term lesson inherent in all this for our array of Spring Training invitees as they attempt to play their way into our good graces? Perhaps it’s if you can’t say goodbye as a champion, then at least stay as late into the fall as you can.

Immerse yourself in thirteen Amazin’ playoff and World Series wins — plus 114 meaningful, memorable, milestone victories from the Mets’ first thirteen regular seasons — in The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), the perfect way to say goodbye to winter and hello again to baseball.

But of all those Met finale stories, the best one belongs to The Glider. That photo is perhaps my favorite Mets image of all time, and I got the chance to tell Ed that this past summer…saw him at the Feast of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in Williamsburg (and that’s old school, pre-hipster Williamsburg). And just the mention of that look on his face brings that look right back to his face, 43 years later.

Hi Greg,

The Glider always held a special place in our hearts during that 1969 season. As fans, we all knew that at 36, his days were over but also knew there was something sweet and special about this one particular gentleman. His son suffered with cerebral palsey, he had to endure the indignties suffered all by African American ballplayers but even more so those on the fringe who had to literally way outperform their caucasion teamates for a spot on the roster. Yet he always had a smile on his face. And the poetry man had a long career in baseball which never gave him even a glimpse of what it felt to be in a pennant race, no less be in a world series. He if anyone, knew it was his only shot and appreciated it even more than his young teamates whose careers were ahead of them. He took upon himself the role of the veteran player leading the kids in the clubhouse. No easy chore when he could no longer do it by leadership on the field like Clendennon, Cardwell, Taylor and other vets. Just shows how vital he was and how the young kids literally loved him.

Remember the greeting he got after rounding the bases against St. Louis, clapping his hands to savor the special moment of his career? That love the players had for him was quite evident as they greeted him in the dugout. Some were waiting for him outside the dugout. Many were crowded on top of the dugout steps. They all hugged him and slapped him on the back with such a demonstration of emotion it was obvious It more than just the usual congratulations (made even more celebratic in lieu of the added excitement of that special evening) in which they greeted Don Clendennon a few minutes earlier.

Ed was released by the Mets and he was bitter about it, however, that did not mean the organization did not care about him and gave him a job in the P.R. Department. Even more respectful was inviting him back for opening day. We in the stands had no idea he was there and thus as the Mets were getting their world championship rings we suddenly heard the name Ed Charles announced over the P.A. system and saw him running out of the dugout, wearing an open trench coat, waving both arms high to the fans as he to get his ring. All the players along the first base line applauded him and I think he got the longest ovation of all the players. You know how much that meant to us if nearly 43 years later the specific memory of that moment is still vivid in my mind to this day among the mostly clouded memories of the rest of the day’s events.

In an exchange of comments a year ago about Charles, I was taunted by some about a .207 hitter being a valuable member of the team. That shows how little they understood – or could appreciate.