Year Books (as opposed to the Official Yearbooks available at concession stands or by sending $1.50 to Shea Stadium, Flushing, NY, 11368) are designed to easily entice historically minded readers. The formula makes sense on its surface. Something happened; something else happened; another thing was going on at the same time, too. You measure your thread, you tie your events/trends together, and — presto! — you have something potentially profound. That’s the idea, anyway, whether your focus is a year in baseball or a year examined within a wider sociological or cultural scope.

Someday I want to write a book titled or maybe just subtitled The Year Nothing Changed, though I don’t know what year it will refer to. My goal is to declare for the record that not “Everything Changed” in a given twelve-month span simply because a cynical editor or publisher thought pretending it did would goose non-fiction sales in the here and now. But to be fair, some things inevitably change if you give all things 365 days to strut their stuff. The world almost never succeeds at playing freeze tag.

Hmmm…maybe I should revise my concept to The Year Nothing Much Changed.

However much actually evolves or is of resounding consequence or just happens to be fun to relive when you limit a book’s field of vision to January 1 to December 31 (or, if it’s baseball, the end of the previous year’s World Series to the end of “your” year’s Fall Classic), then you need to make your raw material live up to its billing. I’ve read authors contort themselves in their attempts to convince their readers that this year in this here book encompassed everything you could possibly want from a year. If it snowed, it was a storm that blanketed everything in sight. If it rained, the ground never grew wetter. If it did neither, then the days were uncomfortably parched as [POLITICIAN] ran for office, [SONG] played on jukeboxes, [SLUGGER] swung for the fences and gas cost [COMPARATIVELY LITTLE] a gallon. The gymnastics to make it all work coherently can be positively frightening.

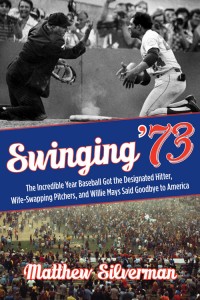

I’m pleased to report Matthew Silverman [1] generally sticks his landings in Swinging ’73 [2], which carries the ambitious subtitle Baseball’s Wildest Season and then makes sure to add another subtitle so we’re persuaded in advance that it was “The incredible year that baseball got the designated hitter, wife-swapping pitchers, world champion A’s, and Willie Mays said goodbye to America.”

Matt — my friend of several years and companion at many Mets games, so there’s your full disclosure — had me at “’73,” but I understand why a surfeit of information was loaded onto the cover. Not everybody lived through the 1973 major league season or the months immediately surrounding it. Not everybody was 10 years old as I was, forming impressions that have lasted a lifetime. Not everybody had a significant chunk of their worldview formed in 1973.

I did. But if you didn’t, you have Matt, and he’s an able and affable tour guide to what you might have missed. It probably helped his cause that he’s just a wee bit younger than I am and freely confesses to not having paid attention to 1973 while it was in progress (whaddayawant from the guy — he was eight). Matt learned the basics in the years that followed but grew mighty curious to dig at what lay beneath them. That sense of personal discovery does the tone of Swinging ’73 good, allowing the author to implicitly share his delight at all that he’s found.

Was 1973 wild? I would have said so coming out of it on my eleventh birthday (12/31/73) and Matt’s book didn’t change my mind. The non-baseball portion attests to the vibe in the air — a vice president was resigning, a president wasn’t far behind him and then came Maude — while our grand old game definitely included some unprecedented twists. Like the first DH, Ron Blomberg. Like the innovative Fritz Peterson-Mike Kekich exchange of families. Like the ominous arrival onto the scene of George Steinbrenner. Like the tearing down of the House That Ruth Built and the imminent toppling of the home run record the Bambino set.

Geez, and that’s just the Yankee angle — and the Yankees fell out of their race in August (to at least one chum’s dismay [4]). They’re not even the focal point of Swinging ’73 but Matt was sharp enough to make them one of his prisms. They always did know how to make news. The real baseball heroes of his story, however, are the eventual world champion Oakland A’s and, to our parochial interests, the National League Champion New York Mets.

Matt treats both entities with enthusiastic reverence, stressing the A’s credentials as all-timers and soliciting the thoughts of a cache of Met players for whom 1973 was their career pinnacle. The A’s deserve their praise, even if they earned it at the expense of our second world championship in five seasons. When you read Matt’s World Series account, you will come to truly admire this opponent from Olympus.

The Mets we hear from here form a somewhat different crew from those whose recollections you usually read in books like these. Matt gives us Matlack [5] and Theodore and Capra and Staub and Hodges (Ron) plus a bit more Garrett than commonly comes up in a Metsian consideration of the Age of Miracles. It was a keen call on Matt’s part. Though only four years separated 1973 from 1969, a genuine interpretation gap exists between the two sensational surges. The Mets most strongly identified with 1969 who endured to make it to 1973 never seem all that excited to talk about the year when they almost won it all. When Tom Seaver announced Mets games, he gave me the impression that he basically went on hiatus after striking out 19 Padres in 1970. That’s how little he brought up 1973 (and how much he talked about 1969). Similarly, if you’re fortunate enough to spend a few minutes chatting with a Koosman or a Jones or a Kranepool, which I have, their calling card is the time they won the World Series, not the time they dazzled a city just to get there.

It’s an understandable impulse on their part, but that leaves roughly half a roster for whom 1973 was it in terms of World Series, not to mention playoffs. Those Mets have compelling stories and Swinging ’73 provides a wonderful forum for telling them. Reading the book and hearing Matt discuss it on multiple occasions was like being granted a seat at the 40th anniversary commemoration the Mets couldn’t be bothered to arrange for this team that worked undeniable wonders.

Wonders deserve our awe. So do the men who forge them and, yes, the years in which they are forged. The Mets apparently require reminding of that basic fact of fandom.

The Cardinals, whatever your opinion of ’em as they’ve played on this autumn, didn’t become the Cardinals by dint of an online survey or a sophisticated algorithm. They simply never stopped being the Cardinals. The winning is no small thing but they were the Cardinals even when they weren’t regularly going to playoffs and they always saw fit to underscore what being the Cardinals meant. There’s probably some connection between how the Cardinals present their heritage to their fans [6] and how their fans see themselves as that heritage’s co-guardians [7]. Nobody loves dressing in red enough to do so without a proprietary feeling for what the act epitomizes.

And nobody out Cardinal way [8] stopped revering their tradition because some Octobers ended sooner than others.

Perhaps it’s because the Mets have come to process the majority of their October experiences as a matter of how far they didn’t go, but this organization’s decision to tacitly dismiss 1973 in particular as something markedly less sacred than 1969 or 1986 represents a lack of appreciation for and understanding of what actually happened four decades ago. Never mind that the Mets didn’t beat the A’s. The 1951 Giants didn’t win their World Series, but neither then nor now have those entrusted with tending that team’s legacy doctored Russ Hodges’s call so it blares, “THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT! BUT THEY FAILED TO SECURE THE OVERALL CHAMPIONSHIP! SO LET’S EVENTUALLY BARELY ACKNOWLEDGE THEIR INCREDIBLE ACHIEVEMENT!” The Giants, thousands of miles removed from the spot where Bobby Thomson’s ball landed, eternally toast [9] the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.

The Mets determined handing out a sponsored deck of playing cards covered their obligations to remember the tidal wave of Belief that washed over Flushing on its 40th anniversary.

The final two games of the 1973 World Series were played over a three-day weekend that no longer exists. Veterans Day, long observed on November 11, had been transformed, Armistice date [11] be damned, into a Monday holiday in 1971 and would stay as such through 1977. Because we had off from school on the fourth Monday in October, my parents took my sister and me to the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskills the preceding Friday. It was there that I watched as much of Games Six and Seven as I could. Technically I was heartlessly forbidden from tuning in — punishment I was receiving for not packing my fancy sports jacket as explicitly instructed —but the ban ultimately proved unenforceable (not that I haven’t found myself haunted by the threat [12]). I was definitely watching when the ninth inning of the seventh game of our second World Series reached its armistice.

I don’t recall if it was because not repeating the feat of 1969 disturbed me to the point of sleeplessness, but I awoke the morning after uncharacteristically early. My older sister, with whom I was sharing a room, was up and at ’em, too, so with little left to do at the Raleigh until my parents were awake and ready to check out, Susan and I did what guests in the Catskills did when there were no meals being served. We went to sit in the lobby.

It was empty downstairs for quite a while, save for us and the desk clerk. Eventually, however, we were joined by a stack of that morning’s Daily News, the extremely thin edition shipped north to towns like South Fallsburg. I bought a copy and flipped through the sports pages, stopped cold by Bill Gallo’s cartoon. It showed Yogi Berra changing a few letters in a sign bearing a very familiar topical phrase while Basement Bertha looked on in sympathy.

“What’s ‘bereave’ mean?” I had to ask Susan, who had already taken the SATs.

“It has to do with being sad,” she explained.

Ah, YA GOTTA BEREAVE…yeah, I get it. Gallo’s humor seemed all too appropriate that mournfully quiet morning. But I didn’t bereave for long. Everything that preceded Games Six and Seven — the timely recovery from multiple injuries; the divisional deficit wiped away [13] in a veritable blink; the legendary center fielder bidding his countrymen adieu [14]; the muttery manager phrasing our odds awkwardly but accurately; the slight shortstop standing up for his smallish self [15]; the indomitable pitchers who could barely be touched [16]; the rallying cry heard ’round the Metropolitan Area; the astounding bounces [17] that coalesced into an Amazin’ ball of virtual unstoppability — felt too life-affirming to allow a Mets fan to get bogged down in the grieving process over a pair of contests that didn’t go the Mets’ way. They were the only things that hadn’t since August 31.

The 1973 Mets won a division [18], won a pennant [15] and, for how they attained those victories, won our faith forever after. Their loss of the World Series — legitimate George Stone flashbacks notwithstanding — veers to the incidental when considered in this context.

Or to put it in modern conference room parlance, 1973 built the Mets brand and imbued it with its key core equity. For those who don’t require a PowerPoint presentation, 1973 is why we Believe with a capital B. If Tug McGraw (whose spirit inhabits Matt’s book) had spouted a less relatable credo than “You Gotta Believe,” it wouldn’t resonate to this day every time a whisper of a hint of a chance pokes its head just barely above the surface of likelihood. Others might attempt to co-opt it [19], but it’s ours. The experience it stands for informs our soul like nothing else across the five-plus decades there have been Mets.

And it came from 1973. Due respect to Archibald Cox, Billie Jean King, Secretariat and Dark Side Of The Moon, that’s what definitely changed during that year, and for the likes of us, its ramifications were indeed wild. Tug and his teammates filed the copyright forms on behalf of all of us, whether we were around to Believe then or not. It was truly negligent of the Mets to not celebrate what it all still means to us in 2013. I’ve heard tell the folks in the counting house did a short-term cost/benefit analysis [20] and decided a 1973 Day that went beyond the distribution of playing cards wasn’t a surefire draw, so they skipped it. I’d respond — in the kind of language they might grasp — that brand equity doesn’t activate itself.

I don’t know what will change in 2014, but I hope the Mets’ reluctance to fully embrace the Mets does.