Aesthetics aside, the Mets’ extended residency in Philadelphia is going pretty well: three of four games have been captured, with one still waiting to be bagged. We’ve seen what Jonathon Niese can do for eight innings when his bullpen needs as much of a blow as he can provide it, we’ve seen how far Lucas Duda can belt a ball in order to prevent a contest from winding its way to a seemingly inevitable fourteenth inning (this baby took only eleven) and we’ve seen an area where the fourth-place Mets definitively outclass the fifth-place Phillies.

We have the better mascot.

Mr. Met hasn’t joined his team at Citizens Bank Park for these five dates, yet he wins by default. He kicks the ass of the overexposed Philly Phanatic, if in fact the Phillie Phanatic has an ass. Who knows what that thing’s packing down below?

The Phillie Phanatic is a certifiable superstar among mascots, though like Derek Jeter, you sometimes wonder what all the fuss has been about. TPP is expert at drawing attention to himself, but Howie Rose may have nailed it on Saturday when, in describing the large green fella’s pregame prop-driven antics, he termed the Phanatic the Kenny Bania of his trade. Seinfeld viewers will recognize the reference as something less than flattering.

Mr. Met, however, is the thinking fan’s mascot and certainly no hack comic. He’s the mascot for fans who use their head. With a head that size, Mr. Met is an aspirational figure for would-be baseball intellectuals everywhere.

The Mr. Met who meets and greets us at Citi Field can trace his roots back practically to the dawn of the franchise. He was a face on rainchecks, a model for merchandise and personified in paper mâché by industrious Shea Stadium ticket-seller Dan Reilly, but his modern iteration is celebrating his twentieth-anniversary season this very year.

By 1994, Mr. Met had been in mothballs, figuratively and literally, for quite a long time. The Mets as a franchise weren’t much more in evidence. The 1994 Mets were actually a feisty, youthful unit that played respectable baseball most of its strike-shortened season, finishing 55-58 and giving habitual diehards like myself a hint that life could go on even in the wake of the Mets’ spiritual demise of 1993. Yet most of New York didn’t notice they existed, not after the 59-103 debacle of the year before, not in the shadows of so much else of a sporting nature going on. The Rangers were skating toward a Stanley Cup, the Knicks were dribbling into the NBA Finals and the Mets hopped up and down shouting ineffectually to anyone who bothered to listen, “HEY! OVER HERE! WHAT ARE WE — INVISIBLE?”

For all practical purposes they were, so they needed something that was going to make somebody stop and do a double-take. They needed AJ Mass.

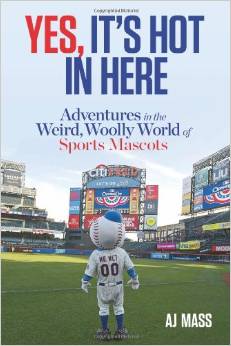

AJ Mass picked up the Mr. Met gauntlet and ran with it…or walked as best he could given the constraints of the costume he was issued. He explains how the sacred responsibility of being Mr. Met fell to him in the engaging memoir/instructional, Yes, It’s Hot In Here: Adventures in the Weird, Woolly World of Sports Mascots.

You might think, in light of how depressingly out of fashion the Mets had fallen after 1993, that the best minds Mets management could gather would come together, research the resources at their disposal, consider the depth and breadth of New York National League heritage and revive Mr. Met because there was no greater touchstone of true Metsiana. But, no, that’s not exactly how it happened. The Mets had gotten themselves aligned with the Nickelodeon cable channel to build an amusement park behind the outfield fence at Shea Stadium. Nickelodeon Extreme Baseball, it was dubbed, a proposition alluring enough for a young, unemployed Mass to audition to take part, for $7.50 an hour, in its ambitious distraction of a sideshow.

The whole thing was such an overwhelming success that it was gone by 1995, but the one enduring element of its slime-slathered legacy delights fans young and old to this day. There would have been no Mr. Met redux without Nickelodeon prodding the mascot out of the attic and it’s fair to argue Mr. Met wouldn’t have kept delighting fans had not Mass so committed himself to inhabiting the role.

Mass was Mr. Met from 1994 to 1997, though at first he wasn’t quite the Mr. Met we know today. The costume (which matched his body type, allowing him to get the gig over others who tried out) was a more complex bundle of “wires, springs and levers” that one would imagine. And Mr. Met’s awkwardly constructed self wasn’t permitted to show his oversized face at Shea on a given day or night until the seventh-inning stretch, when he and a troupe of dancing baseball gloves — a feature even I don’t remember — strutted their stuff to steadily increasing audience approval.

That was all Mr. Met did in 1994. Maybe it was for the best that the strike came and washed away the Nickelodeon slime from Shea. The “Extreme” business disappeared, but Mr. Met stayed. His costume became less onerous, he was given more flexibility and the Mets…well, the Mets kind of didn’t know what an asset they had on their hands, according to Mass. Reading the author’s recollections of how he was left to essentially fend for himself — his wallet was stolen from his unprotected locker; he was directed to stick his head in a Hefty Bag and ride a bus to the All-Star Game at the Vet; he was regularly spoken down to by his so-called superiors as if there wasn’t a fully cognizant human being inside his uniform — you can’t help but think of how the Mets still don’t know what to do with their most valuable properties. Look at how they stubbornly sat Juan Lagares a few weeks ago.

Mass’s Mr. Met grew the brand, as they say in Corporate America, but he didn’t always get to take the character where he thought it could flourish. One vignette he tells is about the time he thought to wave a broom when the Mets swept a series. His supervisors told him, no, don’t do that, it’s not the Met way. What wasn’t, he wondered — being happy about a Met winning streak? Conditioned by Mr. Met’s scrupulously classy behavior these past two decades, I find it hard to imagine Mr. Met brandishing a broom in those rare sweeping circumstances (whereas such a gesture and then some would surely come instinctively to the Phanatic), but, really, what would be the harm? Firing up the defeated opposition as it filed into its clubhouse? Getting some 0-3 Rockies mad that somebody in an enormous baseball-shaped head was basking in his club’s success which also happened to be their fleeting failure? Planting the seeds of horrible revenge the next time that team came to town?

As you can tell from my philosophical mulling, Mass has produced a thought-provoker for any Mets fan given over to thinking through what everything that makes the New York Mets tick. But if you’re just sort of curious about how the mascot world operates or you’d just like to lap up a little furry gossip, Yes, It’s Hot In Here has you covered, too. There’s much beyond Mr. Met to this book. We learn, among myriad other things, that the Phanatic is actually a most solid citizen; the San Diego Chicken would be more accurately classified a Southern California jackass; soccer matches don’t represent a natural habitat for mascots; and (as has already been publicized quite thoroughly) when the Secret Service is protecting the head of state, it displays no sense of humor whatsoever…whatever the size of the head you’re wearing.

Mr. Met keeps his thoughts to himself. Mr. Mass lets them fly on every page. They embody two different personas and two different approaches, yet both show they know plenty about pleasing a crowd.

I got to bump fists with Mr. Met during my trip to New York last weekend, and it was a nice little thrill. Mr. Met is a great mascot among many forgettable ones- I’m sure working inside that giant baseball head makes for interesting tales, so I’ve added Mass’ book to my reading list.

Phillie Phanatic isn’t bad despite dumping popcorn on a ‘Mets fan’ Saturday, or the despicable nature of his Phanbase. At least he is original. The mascot that grinds my gears is Mr. Met’s third rate ripoff, Homer the Brave. Mr. Met should lawyer up.

My son and I watched Saturday’s Met win from the Terrace (Upper) Deck in Citizen’s Bank Park. We could clearly see that the “Mets Fan” recipient of the popcorn-over-the-head was an actor on the Phillies’ payroll. Any other interloper on the dugout roof without permission would’ve been hauled off by the cops. This guy had multiple TV cameras following him and the Phanatic.

The Phanatic is kind of like the attention-starved clown in the last row of the classroom: he’s entertaining if you don’t get close enough to be drafted as a straight man or worse, a prop.

Great showing by Mets fans in Philly, by the way. Hometown fans were clearly irritated by the orange-clad 7-Line group, which occupied a whole section above short Left Field.

Mr. Met rules, but the Phanatic gets points in my book by pissing off Tommy Lasorda to no end during the Dodgers visits to the Vet.

I have a sneaking fondness for the Phanatic, because its costume was created by the parents of a friend. But yes, it’s Mr. Met, hands down.

I like Mr. Met for his ever-present, infectious smile. I’m pleased he has recently been reunited with his long-lost paramour, Mrs. Met. (Who says the Mets aren’t investing in personnel?)

When recently buying a Mr. Met baseball cap — which has since elicited some admiring comments — I learned about a similar baseball-headed mascot, Mr. Red, who apparently predates Mr. Met and sometimes sports an old-fashioned mustache.