As a seven-year-old Mets fan in my first full season of rooting, I gravitated to Ray Sadecki, who passed away Monday at the age of 73, as my favorite Met pitcher who wasn’t Tom Seaver. Seaver ascended to a permanent pedestal on a level all his own in 1969, so in the vast space between him and pitchers who weren’t otherworldly, there was plenty of room for a solid southpaw to garner some secondary allegiance among the impressionable set in 1970. On those defending World Champions who outpitched the National League (best staff ERA, most staff strikeouts) but couldn’t hit their way out of a paper bag (ninth in batting average, tenth in slugging percentage), you couldn’t go wrong with whatever righty or lefty you chose to soak up whatever residual fealty you hadn’t already devoted to Tom Terrific.

For non-Seaver starters, Jerry Koosman’s face burst through the front page of The Sporting News in approximately every third pack of cards I opened that summer. Gary Gentry flirted hard with a no-hitter in Chicago. Jim McAndrew honorably repped Lost Nation, Ia., winning (and losing) in double-digits. Nolan Ryan occasionally harnessed his unbelievable stuff (8.5 K/9 IP, including 15 in his first start of the year), though too often he didn’t (6.6 BB/9 IP, including 8 in his last start of the year). Out of the pen rode Tug McGraw, and what kid back then wouldn’t be quickly drawn to a McGraw? Tug was the lefthanded complement to Ron Taylor, who Topps informed me held a degree in engineering and was about to engineer 13 saves for a third year in a row. Plus there was Danny Frisella and his indefatigable forkball.

Yet amid that sub-Seaver bounty, I went with Sadecki, a man asked to help defend a championship he had nothing to do with achieving, having been a Giant rather than a Met in 1969. Initially, it was based on his name. “Ray Sadecki.” Never mind how it looks. Listen to how it sounds. Hear it not in your voice but in Bob Murphy’s. “And pitching for the Mets, the lefthander, Ray Sadecki.”

Doesn’t that sound great? I didn’t know the spelling before I heard it. I wasn’t necessarily sure where the first name ended and the last name began or if there was necessarily any daylight in between. “Raceadecky.” Maybe he went by just one name, celebrity-style. Maybe the Mets had an icon on their hands. Like Twiggy. Or Lulu.

Once I deduced that “Raceadecky” was Ray Sadecki, I followed his stats in the Sunday papers and warmed to him even more. Sadecki and Seaver, by my interpretation of the weekly numbers, were carrying this team. Whereas everybody else was muddling along around or under .500, Tom and Ray won all the time. Tom was 14-5 at the All-Star break, Ray 7-2. If everybody was performing up to their standards, the Mets would have been well ahead of Pittsburgh instead of a game-and-a-half behind them.

Seaver slumped to 18-12 in the second half. Sadecki surged to 8-4, which is to say that while I was disappointed Tom didn’t win 20, I was thrilled that Ray finished with twice as many wins as losses. The next year, Ray was 7-7, which I fully understood was a comedown from 8-4, but I liked what I considered the “consistency” of how Sadecki achieved .500: After falling to 5-5 in late August of 1971, his next four decisions were a win, a loss, a win and a loss. I have since learned that would indicate “inconsistency,” but he didn’t lose more than he won and thus Sadecki seemed the epitome of comity.

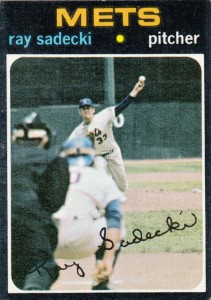

In recalling my childhood fondness for the pitcher whose name and numbers captivated me when I was seven and eight, I sought out an image of one of his baseball cards from that period. The 1971 model uncovered a lost memory of sorts, and I don’t misplace too many memories. It may not even been a memory as much a feeling. On the front, we see Sadecki in action. He has wound up, he is in the process of delivering, he is just, at the moment of photography, releasing the ball from his fingertips. From our vantage point behind home plate, we can’t see the batter, though we know he is righthanded. We see an umpire, but can’t identify him. The catcher, though, is easy to make out, for there’s a visible zero beneath his backwards batting helmet.

That’s Duffy Dyer, ol’ No. 10, crouching to catch Ray Sadecki, ol’ No. 33. It is afternoon at Shea Stadium (we see another “0” in the picture from the “410” marker in center…back when outfield distances stayed stable almost every year). As I was examining the picture, it gently occurred to me that this battery made all the sense in the world because if Sadecki was throwing to Dyer, it was probably during the back end of a Sunday doubleheader from 1970.

I had no proof, other than the sense that on a staff featuring so much young talent, Seaver in particular but also Koosman and Gentry were going to get priority to stay in rotation. When you had a doubleheader, you’d be inclined to use somebody you felt comfortable being flexible with…somebody who felt comfortable being flexible. Ray Sadecki, the veteran starter who came up with the Cardinals a decade earlier, was the one who’d get slotted where he was needed depending on the situation.

Thanks to Baseball Reference, I was able to discern that of Ray Sadecki’s 62 starts for the Mets between 1970 and 1974, 10 of them came in doubleheaders and 9 of them came in second halves of doubleheaders. Seven of those doubleheader starts were at Shea; three, in 1970 and ’71, came on a Sunday (perhaps explaining why I was driven to track down his statistics in the Sunday Times).

“I’d love to be in the rotation,” Sadecki said after five-hitting the Braves in 1971, when he was the elder statesman of the staff at 30. “But who are you gonna sit down for me? I’ll wait for the next doubleheader, or the next time somebody turns up lame.”

I could go through the box scores and determine who actually played behind Ray Sadecki and in front of Duffy Dyer on such Sundays, but I’ll go with the mind’s eye and assume Dave Marshall — who was traded to the Mets with Sadecki for Jim Gosger and Bob Heise two months after the 1969 World Series — was in right and Teddy Martinez was filling in at short or second. This was life when you kept close tabs on the early 1970s Mets: second games of twinbills, your backup catcher, your fourth outfielder, your utility infielder and, of course, your swingman. Most of the time you looked to Seaver and Shamsky and Harrelson and Grote and so on. But you needed an entire team to compete and contend. Even when you had as much pitching as the Mets usually had, you needed a guy who had been around and who would do what it would take.

You needed Raceadecky.

The more I thought about the legacy of Ray Sadecki, the shall we say “swingy-er” he became. He was a starter among all those more celebrated starters, yes, but he was a reliever, too. When you get to 1973, when the Mets competed just enough to contend and contended just enough to prevail, Ray was a part of it, but a different part of it. He was definitely more a reliever than a starter under Yogi Berra than he was under Gil Hodges. He could still go both ways, but came mostly from the bullpen. Down the stretch in ’73, McGraw wasn’t the only lefty reliever converting nonbelievers.

Ray Sadecki saved perhaps the most remarkable game of that September, taking over in the fifteenth inning in Montreal on September 7 and nailing down a 3-2 victory in which Tug had pitched 5⅓ for the win (and Mike Marshall went 8⅓ only to lose). And Ray was the winning pitcher on the night of September 20, pitching four innings and striking out six Bucs at Shea before Ron Hodges drove in the deciding run in the thirteenth. Sadecki had a little help in the top of that inning; after giving up a long fly ball to Dave Augustine, he recorded the final out on a 7-6-2 double play, Jones to Garrett to Hodges, when Richie Zisk attempted to score from first.

That was the ball that hit the top of the wall but didn’t go out, arguably the single most miraculous play in regular-season Met history. It was thrown by Ray Sadecki — same as the final out of the fourth game of the 1973 World Series, a more routine resolution. By striking out Bert Campaneris to preserve Jon Matlack’s 6-1 lead, Sadecki was credited with a save (under the more generous scoring rules of the day), a nice companion to the World Series W he inked onto his dossier nine years earlier when he beat the Yankees for the Cardinals in 1964’s Game One.

The Mets won eight World Series games at Shea Stadium. Two of them were captured in what has come to be known as “walkoff” fashion. The one that concluded 1969’s festivities was completed by the man who started it, Koosman. The other five resulted in home team saves, each registered by a different Met. Three of them were the product of their team’s primary fireman: McGraw in Game Four of 1973, Jesse Orosco in Game Seven of 1986 and Armando Benitez in Game Three of 2000; one came from a future Hall of Famer, Ryan, in Game Three of 1969; and one was the handiwork of Ray Sadecki, who won 20 games for the ’64 Cardinals but didn’t put on airs about taking on whatever task was at hand for the ’73 Mets. As Gil Hodges put it a couple of years earlier, “He has the right approach. He’s able to accept whatever job comes his way.”

There is something singular about Ray Sadecki that goes beyond his aesthetically pleasing name and triple-word score in trivia value. We go back to that job description: swingman. It means someone who can swing from relieving to starting to relieving and be effective enough at it so you don’t hesitate to ask him do both. Nobody in the 53-year history of the New York Mets was a more relied-upon swingman than Ray Sadecki. No pitcher swung more (which reminds me: Ray swung for a .213 average as a Met hitter, the best batting average by any Met pitcher with at least 100 plate appearances).

In the six seasons in which he was a Met — all of 1970-1974, until he was traded with perennial prospect Tommy Joe Moore for elusive-turned-erstwhile Never Met Joe Torre, and then his brief pre-retirement Recidivist Met encore in 1977 — Sadecki pitched in 165 games, starting 62, relieving in 103. According to Baseball Reference’s Play Index tool, no Met who started that many games ever relieved in so many and no Met who relieved in so many games ever started as many.

It’s not even close. And if you infer by his situational usage that Sadecki must’ve been little more than sacrificial spot starter when called upon, infer otherwise. Ray threw 13 complete games, including three shutouts, as a Met. Not bad for someone who never fully cracked the Met rotation or started more than 20 games in any of his Met seasons.

Today we’re used to every pitcher being assigned a role and being stuck narrowly inside it until further notice. It takes a veritable sea change to use a pitcher to do something he wasn’t doing last week. In 2014, we witnessed a rarity: a starter, Jenrry Mejia, not only moving to the bullpen, but becoming the closer, roughly following the trajectory established in the 1960s by McGraw. Thing is, Mejia (who came up as a reliever in 2010, got hurt and was reborn as a starter in 2013) isn’t going to start for the Mets again unless something goes amazingly awry.

We saw Aaron Heilman struggle as a starter when he came up in 2003, eventually excel — he threw a one-hitter early in 2005 — but then be consigned to the bullpen, never moving back to starting, even when the Mets were groping for a trustworthy arm in the years to follow. We also saw the Mets attempt to do something Heilmanesque with Dave Mlicki, who started almost exclusively in 1995 and relieved almost exclusively in 1996. But then Dave was shifted back to the rotation in 1997 and stayed there without another bullpen appearance before he was traded to the Dodgers in 1998.

Conversely, you’ve occasionally had Mets who were asked to get used to the majors as relievers or refine their form as relievers but whose predominant role on the Mets was starter. Or you’ve had starters who faded from the rotation and wound up relegated to the pen. You pretty much have to go back to Terry Leach to find a pitcher you could think of as a true swingman. Leach saved the 1987 season when starters were dropping left and right from injury, but once a wave of health took hold, Leach was back in the bullpen for the entirety of his remaining time as a Met. And prior to Leach — excepting for McGraw’s handful of starts to rouse him from funks in 1973 and 1974 — smooth shifting between roles wasn’t done all that much, not even in the pre-save era, at least by the same pitcher on a recurring basis. Galen Cisco came closest to pulling it off, starting 61 times and relieving 65 times between 1962 and 1965, the four worst seasons in Mets history.

But Sadecki did it continually and did it effectively for mostly good teams, including a league champion. In four of his five full Met seasons, he started at least 10 games and relieved in at least 9 games. In his best WAR year as a Met, 1971 (when his won-lost record was a “consistent” 7-7), he started 20 times and relieved 15 times. By modern metrics, he was worth 3.4 wins above replacement in ’71. Only Seaver and McGraw delivered more pitching value…and you generally knew whether they were going to start or relieve.

You never knew with Raceadecky. But once I figured out he was Ray Sadecki, I sure knew that I liked him.

In this era of hyper-specialization and guys insisting that they have to know their “role” (which, news flash, is to get batters out), we call guys like Ray Sadecki a swing man. We used to just call them pitchers. Never a star, but got the job done. RIP.

And as Murph liked to give a shout out to hometowns, we were always reminded that Ray was from Kansas City, Kansas.

Never a star, thus what a stunner to learn he once won 20 games. 20 games!

The decline of the doubleheader as a thing certainly cut down the need for guys who could start and relieve, in addition to the mentioned shift toward specialization. So the swingman was more of a necessity in the Sadecki Era. Like you I felt the Mets must have had one of the better ones out there. Still the guy I think of when I think of Met 33s, and not Mat Harvey or John Maine or, you know, Kelly Stinnett or Eddie Murray.

Even given the passing from the scene of the regularly scheduled twinbill, he sure did start a lot of games for a guy who wasn’t one of the starters, per se. When you consider how much pitching the Mets had in the years between their pennants, it’s a little unsettling to realize how far they came from winning again in ’70, ’71 and ’72.

Harvey may make the issue moot, but Ray, Barry Lyons and Pete Falcone seem to be the 33s I think of most frequently when thinking of 33.

Nice tribute Greg. I believe Sadecki was traded from the Cards to the Giants for Orlando Cepeda. Some of your Giants fan friends are probably just now getting over that one.

Haven’t heard from any of them regarding Sadecki. I’m thinking they may view him the way we look at Fregosi or Alomar in light of what they gave up to St. Louis — and what they got from us.

Was pointed out somewhere Sadecki was traded for two HOFers in Cepeda and Torre. At least two GMs valued him appropriately.

I read a Giant fans rant after his obituary was posted, “Do not tell any Giant fan Ray Sadecki was a stand-out. We traded Orlando Cepeda for Sadecki and he was not good in San Francisco. Overall record: 135-131, but in San Francisco, allegedly in his prime, 25 to 28 years old, he had three losing seasons and one winning season, 32-39. Cepeda was MVP when he went to the Cards. Giants fans my age and older still can have blood pressure spikes hearing the name of Ray F*^%$%g Sadecki.”

The first in a series of trades that would turn out badly (the Bill White and Felipe Alou trades were actually OK. The pitchers the Giants received did what was expected).

I was almost glad to be in Vietnam for 19 months of his career with the Giants, just so I wouldn’t have to watch him pitch.

I grew up in Kansas city ks. I saw Ray Sadecki play baseball as kid in Klamm Park. He pitched over the top and his fast ball was just a blur. He had a curveball that looked as if it fell off the table as it came across the plate. He not only was a great pitcher. But he could hit to. I seen him hit balls over the dike, that ringed the entire field At Klamm park in Wyandotte county in KCK. As a kid of 11 years old. watching ray mow down the hitters and drive balls over that dike on the fly….what great memories he gave me as child..Thanks Ray for all the games I seen you play.

Sadecki, Dyer, Beauchamp, Martinez…just a few of the guys who roped me into this Mets fandom roller coaster way (way) back when. Once a Met, always a Met, RIP Ray.

Why when any Met (or any ballplayer from our baseball card days) passes I react as if my favorite uncle died. In the Bronx as a 10 year old I used to imitate Sadeckis three quarter to sidearm delivery with a rubber ball against a painted strikezone. A great veteran presence to Seaver Koosman Gentry and McAndrew. RIP – Ray, Tug, Tommie, Gil, and John Milner

Very nice tribute. I also enjoyed the way his name sounded and while not as mindful of his numbers appreciated his flexibility. I think teams today are not appreciating the value of a guy who can start, relieve and fill in different roles as needed. Always though of him as #33 in all time Mets numbers, but that will likely change to Harvey in short time. It’s sad he suffered so much from blood cancer – sounds horrible. In this day and age, 73 is way too young.

[…] much time as we tended to attribute to him) from the worst of torpid Steve Trachsel to the best of handy Ray Sadecki, converted his free agency into a deal with the Softbank Hawks in Japan. No goodbye, either, to […]