I’ve spent a good chunk of the winter sulking about Jeurys Familia quick-pitching or Yoenis Cespedes playing base-soccer or Daniel Murphy bringing the glove up or Cespedes charging off first on a soft liner or Terry Collins being too sentimental or Lucas Duda being unable to make a simple throw home or getting to the big stage only to be cast as the Washington Generals.

And perhaps one day I’ll write about that beyond a single run-on sentence followed by a big sigh.

But I’ve done something else this winter, probably by way of therapy: I’ve charged through the rest of my work to make The Holy Books even more holy.

Years ago I dived into Photoshop to make cards for the nine Lost Mets who’d been denied so much as an odds-n-sods bit of cardboard from some fringe set. I should have known that was only the beginning. I should have guessed that the presence of non-Met cards in The Holy Books would start to bug me and keep bugging me. I should have intuited that it would bother me to have less than a full set of Mets managers with their own cards. I should have divined that once I started putting aside cards of Met ghosts I’d want those almost-Amazin’s to have cards in orange and blue as well.

It took me a while — denial is a powerful thing — but eventually I decided this was something I had to do. I would correct the historical record by making sure every Met before the dawn of respectable minor-league cards — that’s 1980 by my reckoning — got a Topps-style Mets card showing that player in Mets garb.

That meant not just the Lost Mets, but also any Mets around too briefly to get Met cards — the Frank Larys (Laries?) and Ron Herbels and Doc Mediches of the world. Cup-of-coffee guys who had to share space with one or three other young hopefuls on Topps rookie cards — Bob Moorhead and Billy Murphy and Benny Ayala and friends. Guys whose moment in the cardboard sun came years later in specialty sets — Willard Hunter, Joe Moock, Billy Baldwin and their fraternity. Players stuck with black-and-white Tides cards — Jay Kleven and Randy Sterling and others like them.

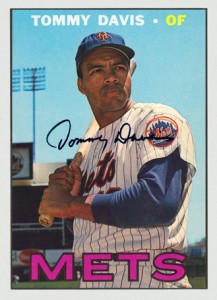

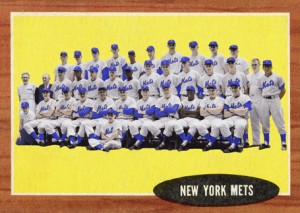

I decided it also included guys whose lone Mets cards featured doctored images of them with other teams — your Larry Burrights and Tommy Davises and Bob Gallaghers. That principle led me, reluctantly at first, to conclude that the ’62 Mets not named Ed Bouchee or Al Jackson deserved cards in which they were really Mets instead of hastily concealed Braves and Reds and Cubs. Oh, and those inaugural Mets needed a team card of their own.

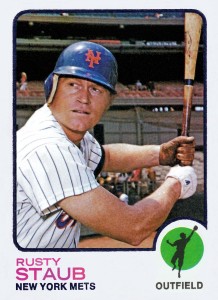

The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards?

The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards?

That left me a first volume of The Holy Books that would be all Mets and Tides, with four exceptions: Dave Roberts, Dick Tidrow, Larry Bowa and Tim Corcoran. By now I don’t need to tell you what I decided about them.

It added up to 158 cards — and an amount of time and money that would have made me scrap the whole project if I’d understood what I was getting into. I bought unused Topps photos and autographed images (which, ironically, I then de-autographed using Photoshop) and scoured yearbooks and baseball-photography sites. Sometimes I transformed photos of guys in other uniforms into Mets, which taught me that an Atlanta away uniform is easily converted into a Mets road jersey, while a Yankees or Phillies home jersey is your best starting point for creating New York (N.L.) pinstripes.

So much for the fronts. But what about the backs? This was the part I feared would be drudgery … but actually turned out to be fun. A player’s statistics told a tale — usually one that took a sad or frustrating turn, since by definition we’re talking about the last guys on rosters. And each player had an actual story, one I had to delve into to create my cardbacks’ diplomatically phrased bios and career-highlight cartoons. (I’m proud to say I never had to resort to something safely generic, such as opining that Jim Bethke enjoys music.)

Learning those stories transformed random guys from long-ago rosters into people whose recollections could have filled a barroom for hours. Every Met turned out to be interesting, having been party to a tragic turn of events, a missed opportunity or — sometimes — a decision that other things were more important. And those stories gave me a window into an era of baseball that now seems impossibly distant.

There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League.

There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League.

’62 Mets hurler Ray Daviault spoke nothing but French before he left his native Montreal for an odyssey that took him to Cocoa, Fla. (Florida State League); Hornell, N.Y. (Pony League); Asheville, N.C. (Tri-State League); Pueblo, Colo. (Western League); Macon, Ga. (South Atlantic League); Montreal (International League — and home!); Des Moines, Iowa (Western League again); back to Montreal; back to Macon; Harlingen, Texas (Texas League); Tacoma, Wash. (Pacific Coast League); Syracuse, N.Y. (International League again); and finally the Polo Grounds.

Another ’62 Met, Sammy Drake, split 1956 between Ponca City, Okla., in the Sooner State League and Lafayette, La., in the wonderfully named Evangeline League, also called the Tabasco Circuit. 1956 was an odd year even by Evangeline League standards: the New Iberia Indians disbanded in May, leaving seven teams on the circuit. Drake’s Lafayette Oilers beat Lake Charles in the first round of the playoffs and were set to play Thibodeaux, but the finals were cancelled because of a lack of interest. The Oilers’ default co-champion status didn’t help them in 1957; they disbanded in June, at which point Drake was in the Army.

While in the Evangeline League, Drake probably heard of the legendary Roy Dale “Tex” Sanner, who’d won the circuit’s batting triple crown for Houma in 1948, hitting .386 with 34 home runs and 126 RBIs. The amazing thing was Sanner had also gone 21-2 as a pitcher with 251 strikeouts and a 2.58 ERA that year, missing the pitching triple crown by one win, eight Ks and a fifth of an earned run — a distinction he lost out on because he jumped ship to finish the year with Dallas. Sanner sounded like some Paul Bunyan of bayou baseball, but he was real — ’62 Met Willard Hunter played with Tex at Victoria in 1957, when both were Dodger farmhands. Hunter was 5-6 in 15 games; Sanner went 12-4 for the year and hit .331. Victoria won the ’57 Big State League title, after which the loop ceased to exist.

Today semi-pro leagues are an oddity, but back then they were an essential part of many players’ rise. Sixteen eventual Mets — including Moock, Shaun Fitzmaurice, Al Schmelz, Dennis Musgraves, Gary Gentry, John Stearns and Bob Apodaca — honed their skills in South Dakota’s Basin League, an amateur summer circuit which began in 1953 and lasted until the early 80s. (Jim Palmer, Bob Gibson and Frank Howard were Basin League vets.)

For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3.

For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3.

Another independent circuit, the Mandak League, thrived in the 1950s as a haven for former Negro League players and African-American and Latin players who’d been driven out of pro ball or refused to put up with the abuse required to stay in it. Before he turned pro, Sammy Drake had a tryout with the faded yet fabled Kansas City Monarchs and got his start in the Mandak League as a Carman Cardinal, a move he made in part on advice from older brother Solly, who told him the largely Canadian league was an easier place to play than the South. After signing with the Cubs, Sammy Drake joined Ernest Johnson as the first black players for the Macon Peaches, and learned all too well what Solly had warned him about.

Race kept some players from the big leagues or delayed their arrival — ask Ed Charles or Al Jackson about that — but players also had to deal with farm systems that were ill-suited for developing young talent. Baseball didn’t dismantle its bonus-baby rules until ’65, and countless careers were short-circuited by bringing players up too early and then leaving the shell-shocked rookies to rot on the bench or in the bullpen. As if that wasn’t enough, players could be undone by internal politics, skullduggery designed to thwart other organizations, or simple incompetence.

Before I started my insane project, Jerry Hinsley was half of a Met rookie card, the less-than-proud owner of a 7.08 ERA in 11 career games. But Hinsley went 35-0 as a high-schooler in Las Cruces, N.M., helping his team to three straight state championships and throwing three no-hitters along the way. The Pirates signed him (with twin brother Larry for company) for 1963, but wanted to keep him from being taken in the first-year draft. So they sent the 18-year-old to Kingsport, Tenn., and told him to pretend he had a sore shoulder. Hinsley didn’t pitch a single inning all year.

Mets scout Red Murff knew about Hinsley and wasn’t fooled. The Mets drafted the young pitcher and found a new way to abuse him — they had him make his pro debut in the big leagues. Hinsley racked up an 8.22 ERA before he was sent down at the end of May, made it back to the majors for a ’67 cup of coffee and retired at the end of ’71 — still just 26 — as an Indians farmhand. If he’d been treated differently, who knows what might have been?

Misfortune destroyed other careers. Dennis Musgraves threw two no-hitters in college and signed a then-record $100,000 bonus with the Mets in ’64. Rushed to the big leagues in July ’65, he followed three strong relief appearances with a seven-inning start against the Cubs in which he allowed just one earned run. The next morning his elbow was swollen and his pitches couldn’t reach the catcher. He’d endure two elbow operations and remake himself as a junkballer, but never returned to the big leagues — his 0.56 ERA will forever be a what-if. Ditto for Dick Rusteck, whose big-league debut was a four-hit shutout against the Reds in June ’66 — followed by a hurt shoulder and a bad elbow. Unfortunately for the likes of Musgraves and Rusteck, Frank Jobe was nearly a decade away from trying a novel surgical procedure on the left elbow of Tommy John, and most sore arms were professional death sentences.

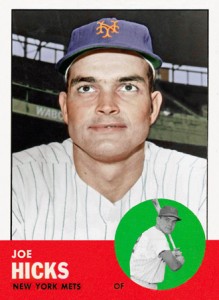

Joe Hicks, who hit .226 for the ’63 Mets, never had one big thing go wrong for him — just a succession of small and medium-sized things. Hicks was signed by the White Sox out of the University of Virginia in 1953 and hit .389 for Madisonville in the Kitty League, finishing the year with a .346 average for Colorado Springs. He hit .349 the next year, then .299 for Memphis in ’55. He was 22 years old, one step from the majors, and Chicago needed outfielders.

Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape.

Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape.

Then there were guys whose highlights came before their debuts — sometimes on bigger stages than you might guess. Ted Schreiber was born in Brooklyn, grew up a Dodgers fan and went to St. John’s. In 1958, with the Dodgers gone, Ebbets Field was home for a handful of Long Island University and St. John’s games. On April 24, Schreiber hit a game-winning two-run homer there. Five years later, he’d play at the Polo Grounds as a Met.

Or take Shaun Fitzmaurice, who’d have given Michael Conforto a run for his money in the hype department if we’d had Twitter in 1966. Fitzmaurice had power and speed that made scouts compare him with Mickey Mantle. While a Notre Dame student in 1963, Fitzmaurice slammed a 500-foot home run against Illinois Wesleyan that’s lived on in college lore. USC coach Rod Dedeaux — who’d help shape Seaver’s career — took Fitzmaurice as an Olympian for the 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo, and he hit the game’s first pitch for a homer.

Fitzmaurice never hit a Met home run, but this one almost counts: In 1961 he played for the U.S. All Stars in the Hearst Sandlot Classic at Yankee Stadium. With two out in the ninth, Fitzmaurice drove a ball 400 feet, tearing around the bases for a two-run inside-the-park home run. The teammate he drove in? U.S. All Stars’ second baseman Jerry Grote, whose double-play partner for the game was Davey Johnson.

One story left me happy about what was instead of wondering what could have been. It’s the tale of Bill Graham, briefly a Tiger and Met. All I knew about Graham was that he shared a name with the rock promoter and always looked like his hat didn’t fit. But there was a lot more to him than that.

The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.

The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.

Graham, the son of a Flemingsburg, Ky., physician, had stepped away from baseball to become a doctor. He completed his degree at Elon College in North Carolina in 1962, then went to medical school at UNC and the University of Kentucky. He came back to baseball at 28, won 12 games for Syracuse in ’65 and helped Mayaguez to a winter-ball title. He was older, wiser and far from the typical prospect.

“I’m at an age now that another year in baseball won’t make any difference, except to steer me either way,” he told a reporter during 1966 spring training. “The hardest thing is to get into medical school, and I worked too hard not to take the opportunity. I like baseball and I’ll see what happens this year.”

What happened was that Graham pitched well in a second go-round with Syracuse and made his big-league debut in Detroit’s final game of 1966. Next August, after a 12-6 season with Toledo, he was purchased by the Mets. Graham made three starts for the Mets; on September 29 he scattered six hits in a complete-game victory against the Dodgers.

It was Graham’s first big-league win. It was also his last professional appearance.

What happened? William A. Graham Sr. was ill, so his son went home to Flemingsburg to care for him. The younger Bill Graham missed the ’69 World Series and the chance to build on an intriguing story.

Or rather, he missed the chance to build on that story.

Graham did well back home in Kentucky. He farmed, developed land and became a mainstay of local government and business, serving on any number of boards and commissions. When he died in 2006, he left Elon a $1 million bequest.

“You spend your life gripping a baseball,” Jim Bouton famously said, “and it turns out that it was the other way around all along.” Not for Bill Graham, though. He approached baseball differently, coming and going on his own terms, and it worked out pretty well.

Beautifully researched, Jason. I would love to see this and more in book form!

The following conversation has happened several times:

My wife: You know more about Mets trivia than any human alive (said in a tone that implies that this was by no means high on the list of reasons she married me)

Me: Oh no, I’m not even close. Not even remotely close.

My wife: Yes you do. Nobody knows more about this stuff than you do.

Next time we have that conversation, I’m going to show her this piece. Mike drop. Jason, this is brilliant. Thank you for taking my mind off the possibility that Murphy and Cespedes could both be Nats, even if only temporarily.

These stories make all the time & effort worthwhile. Excellent stuff.

Just wonderful Hot Stove reading. Thank You!

There was a detailed writeup on the Evangeline League 1946 betting scandal in one of the SABR Publications a while back:

http://research.sabr.org/journals/archive/45-brj-1982/357-the-evangeline-league-scandal-of-1946

The 1987 Cable Movie “Long Gone” was loosely based in the scandal. Still one of the best BB movies ever, IMHO.

And, finally, one of the pitchers on my 1964 Little League team was nuts about Jerry Hinsley, and even patterned his windup after Hinsley’s. As I recall, it was a fast violent windup, and like Hinsley it didn’t help Johnny D. much either. But whenever the name Jerry Hinsley comes up (usually here) Johnny D. is who I think of.

This is awwwwwsome! All these cards are beautifully done Fry. :)

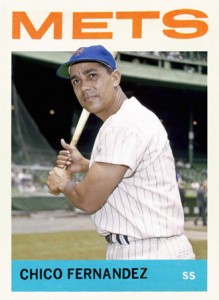

I especially love the Hicks and Fernandez.

Thanks. I deserve zero credit for the Fernandez, Davis or Staub cards — all I did with them was not get in the way of awesome photos. Hell, put the ’64 design around anything and it looks pretty good.

I’ll admit to being proud of the Hicks, though. ;-)

Actually, you do deserve some credit for the Fernandez. That photo originally appeared on the internet “flipped” or “reversed”, with Fernandez appearing to bat lefty. If you worked from that “reversed” image, you knew enough to correct it because Fernandez batted from the right.

That and credit for de-watermarking the Hicks inset photo.

I’ll always claim the 1973 Topps design as my favorite. The player name, team name, simple position logo in color circle….simple, effective, and clean. It allows for the photo to tell the story unfettered. Love it.

The thing to remember about Hinsley is the wacky rules of the day, intended to discourage the Yankees from signing every good high schooler in the country. I’ve tried, but I still can’y figure them all out–and they changed from year to year. But, basically, if you got a signing bonus, you had to spend….well, first it was two years and then it was one of your first two years….in the majors. In the alternative, you’d have to pass through waivers. I think the situation with Hinsley was that he HAD to be in the majors or the Mets would lose him. Until the amateur draft was instituted, a lot of careers were ruined by those rules. Bob Powell spent two years (more or less, his “sentence” being shortened by military service) with the White Sox and got into precisely one game each year…both as a pinch runner. Mets who were “rushed” due to these rules included Bethke and Tug McGraw. The ’65 roster was filled with players who had no business being in the major leagues yet. But it wasn’t the Mets who were to blame; it was the rules of the road at the time. So I can’t see my way to blaming the Mets for the “abuse” of Hinsley. I don’t believe they had a choice. As for trying to “hide” players through “injury”, the Mets (and everyone else) did that all the time…yet another unintended consequence of the rules at the time. BTW, speaking of which, did you do a card for Bob Nash? Bob spent all of 1965 “in the major leagues” without getting into a single game. He spent the first part of the year on the Mets DL and the rest on the Phillies DL. Bob was legitimately recovering from knee surgery, but he still had to be carried at the major league level (once again, those dang rules). We lost him when we activated Yogi and had to drop someone from the 40-man to make room. The Mets figured–Bob being out for the year and all–they could sneak him through waivers. But they couldn’t and the Phils nabbed him. As it turned out, his knees never really got better, which robbed him of the power everyone wanted him for, and he never made it to the majors (not as an active player, at least). What’s one more card, eh?

Nash is an interesting case. He was discussed a while back over on OOTP, which is a great site for baseball-photo junkies. He doesn’t seem to have ever suited up for the active roster, so he doesn’t count as a ghost despite his year as Mets/Phils property.

I didn’t make a Nash card, but I did save the very nice shot of him in Phillies away garb.

You’ve got me further intrigued about the already intriguing Hinsley. The Mets sent him down without losing him, and accounts of that era talk about Casey wanting to bring him north. So not sure what the rule dictated there. Whatever it was, it wasn’t good for him.

Posts like this is a big part of why I come here. Thanks for this, none of which I had ever heard before.

Nice piece. The connection of the Mets to the Hearst Classic is major. In all, 15 Mets participated in the Hearst games at one time or another between 1946 and 1965. Here are just a few. Not only were Davey Johnson, Jerry Grote and Shawn Fitzmaurice in the 1961 game, but Ron Swoboda played in the game in 1962. Ted Schreiber and Tommy Davis played in 1955 and Larry Bearnarth in 1969. Skip Lockwood was in the game in 1963. And how can we leave out two 1962 Mets, Hobie Landrith and Jim Marshall, who played in the 1948 and 1949 respectively. Landrith also played in something called the Esquire’s All American Boys Baseball Game in 1946. The 1944 Esquire’s Game produced original met Richie Ashburn. And lets not forget about another 1962 Met, JoePignatano, who played in Brooklyn Against the World in 1948.

[…] went a little catatonic after the World Series, retreating into creating Lost Mets baseball cards and the comforting routines of work. I never quite figured out why, but I can grasp the broad […]