On February 17 we lost not one but two Mets.

There was no shortage of farewells for Tony Phillips [1], who died in Scottsdale, Ariz., at 56. And that was to be expected — Phillips racked up 2,023 hits over an 18-year career.

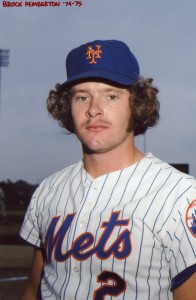

Brock Pemberton [2] was the other Met who died on Feb. 17. His death [3] at 62 in Ardmore, Okla., went largely unremarked in baseball circles, which also wasn’t unexpected. After all, Pemberton collected 2,019 fewer big-league hits than Phillips. His pro career spanned eight seasons, with a ’74 cup of coffee in New York and the merest sniff at one — two games, two at-bats — the next year.

(photo from OOTP [4])

But as I learned making baseball cards for obscure Mets, even agate-type careers contain interesting stories. Pemberton’s dad Cliff was a Dodger farmhand in the late 1940s and early 1950s, hitting for a high average without much power. His son was born in Oklahoma but blossomed at Marina High in Huntington Beach, Calif., where the Pembertons had moved in ’68. (Marina High later produced Kevin Elster [5].) The Mets drafted Pemberton in ’72 and he turned out to be a lot like his dad — a spray hitter who made solid contact without clearing too many fences. Cliff played second base, but Brock was a first baseman — a slightly speedier Dave Magadan [6].

Pemberton’s breakout season was ’74, when he hit .322 with 89 RBI for Joe Frazier [7]‘s Victoria Toros. After the Toros wrapped up the Texas League title, Pemberton learned he’d been granted a September call-up to the Mets. He struck out as a pinch-hitter against the Expos on Sept. 10, but more, well, amazin’ events were in store.

A day later, a 3-1 Met lead evaporated against the Cardinals in the ninth, setting up one of baseball’s all-time marathon games [8]. In the 25th inning St. Louis grabbed a 4-3 lead when Hank Webb [9] picked Bake McBride [10] off first (balking in the process) but hurled the ball down the line; McBride ran through the third-base coach’s stop sign and was out from me to you. Well, at least he was until Ron Hodges [11] dropped the ball.

In the bottom of the 25th, fly balls by Ken Boswell [12] and Felix Millan [13] left the Mets down to their last out. It was after 3 a.m. Yogi Berra [14] sent Pemberton up to the plate, and the rookie nearly decapitated Sonny Siebert [15] for his first big-league hit — almost certainly the first big-league hit seen by the fewest people in Mets history. (John Milner [16] then struck out.)

Pemberton collected three more hits in September, had a brief call-up in ’75, and then was traded to St. Louis with Leon Brown [17] for Ed Kurpiel after the 1976 season. 1980 was Pemberton’s final year in pro ball, and saw him serve as the 26-year-old player-manager of the Macon Peaches. After leaving baseball, he lived in New Mexico, working as a landscaping supervisor for state parks, Indian reservations and colleges.

His obituary is filled with family recollections and in-jokes — his time in California is recalled as “the wildest of times and the best of times (with burning leaves)” and continues with the note that “Brock was a free spirit. He loved the outdoors, fishing, hunting and gardening. He was also a fabulous baker and cook.”

I don’t know what the reference to burning leaves means (though I have a guess), but Pemberton’s family and friends did, and that’s the important thing. If you’re a fan of the A’s, Tigers or even the Mets, you have plenty of memories of Tony Phillips and knew a little something about his life; only the most committed Mets fan remembers Brock Pemberton or knew anything about what he did away from baseball stadiums.

But they were both Mets, both ballplayers, both sons and brothers and husbands. And both gone before what those they left behind had hoped would be their time.

When I first became a fan, the vast majority of the men who’d been Mets were still alive — it was only 14 years since there’d been New York Mets, and the exceptions, such as Danny Frisella [18] and Gil Hodges [19], were tragedies. Now, four decades later, it’s different. Nineteen of the 45 ’62 Mets are no longer with us. There will come a day when only a few are, and then one, and then none, and the other rosters will follow suit, from the ’60s into the ’70s and then the ’80s and one day the teens of a no longer so new millennium.

It’s the way of baseball because it’s the way of all things. And it will be up to us to remember these men who were Mets, from stars and can’t-miss prospects and Hall of Famers to scrubs and did-miss prospects and trivia answers. Like Tony Phillips. And like Brock Pemberton.