One of the great frustrations of being a fan is how different a team can look on successive days. In one game absolutely nothing works; less than 24 hours later everything does. Or vice versa, of course. Players know this far better than we do and respond to it with a studied stoicism that we sometimes misread as bland acceptance; 90% of dumb calls to sports-radio shows (which is to say about 81% of all such calls) start with the fact that fans externalize what players have learned to internalize.

A tolerably good response to this essential unfairness is to turn things around and look at them from the other guy’s perspective. (Actually this is a tolerably good response to everything, particularly in our to-the-barricades age of hot takes.) On Tuesday absolutely nothing went right for the Cubs, culminating in an excruciatingly hapless ninth-inning crash landing; on Wednesday the Cubs stuck their bats out and waited for good things to happen. Meanwhile, for the Mets … well, you get it by now. If Tuesday’s was a game that stubbornly refused to send the Mets away [1],Wednesday’s was a game that never came into view [2].

I was on my couch, happy to be back from nine days overseas and even happier that there was a matinee awaiting me. Being five hours in the future had limited me to a handful of early innings: witnessing the All-Star introductions but luckily missing Terry Collins [3] failing to even secure his own team a participation medal; seeing Neil Walker [4] blast a key home run; and catching a batter or two when the Wi-Fi was friendly. Now I was back, and ready for … well, for not much.

Bartolo Colon [5]‘s location was not what it needed to be, which happens to him sometimes and makes him into the easy target he otherwise just appears to be. Colon looked odd in second-term Reagan gray polyester and grumpily resigned on the mound, knowing it was unlikely that the baseball was going to go where he needed it to. Twice that baseball lingered in the couple of inches of airspace where Anthony Rizzo [6] most wanted to find it, resulting in fly balls so instantly and obviously gone that the normally polite Curtis Granderson [7] barely moved his feet.

The Mets mounted a couple of fitful rallies against a very Colonesque Kyle Hendricks [8], most notably in the fourth when James Loney [9], Travis d’Arnaud [10] and Kelly Johnson [11] awakened with two outs to rap consecutive sharp singles. Unfortunately, Johnson’s hit had to deliver Loney from second base, a task for which express delivery is not an option. As Loney drifted continentally in the direction of home plate, Jason Heyward [12] scooped the ball up in center and hurled it home. The play was neatly symmetrical: one hop between the grass and Heyward’s glove, one hop between the grass and Miguel Montero [13]‘s mitt, and pretty much a textbook illustration of how to throw a runner out at home.

That’s another way to keep baseball from being maddening: appreciate whatever it gives you on the day, even if it’s a highlight for the other guy.

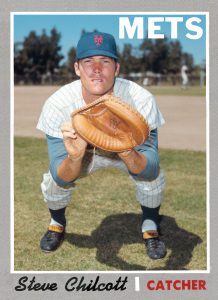

One other thing keeps bugging me, too much to leave for the full post it deserves to receive one day. During a discussion of draft picks, Steve Chilcott’s name came up and I winced, as I always do.

The Mets, you may recall, drafted Chilcott as the first pick in 1966, one place ahead of Reggie Jackson [14]. Reggie became Reggie; Chilcott became a punch line.

What kind of punch line depends on the context. Sometimes it’s that the Mets are and have always been the Mets, ready to screw up their next two-car funeral. Other times it’s that the mid-60s Mets were run by racists who disliked rabble-rousers and other free-thinkers.

Either narrative ignores the fact that Chilcott was a pretty good player: he hit .500 his senior year at Antelope Valley High, with 11 home runs in a 25-game season. Whitey Herzog [16], a key architect of the Mets and the man who should have succeeded Gil Hodges [17] as manager, recalled that he polled the other teams after the ’66 draft and the vote for Jackson over Chilcott was a skinny 11-9.

Chilcott didn’t do much in two stops in ’66, but was having a fine year at Winter Haven in 1967 when his career took a disastrous turn: he dove awkwardly back into second on a pickoff attempt, dislocating his shoulder. The injury never healed properly, leaving Chilcott saddled with constant pain and unable to throw effectively. He tried surgery in 1969 but was out of baseball by his 24th birthday.

That’s half of the story; the other half concerns what the Mets might or might not have thought of Reggie Jackson.

Rumors that race had something to do with the Mets picking Chilcott over Jackson go back to 1969: Reggie told one interviewer that “there are other reasons they didn’t pick me, and it isn’t what they put in the papers. Other people in baseball have told me why I wasn’t drafted by them.”

Mets GM Johnny Murphy [18] rejected that: “We needed a catcher more than we did an outfielder when that draft came up and our reports indicated that Chilcott was a better player, certainly a better prospect. Every time I read about Jackson hitting another home run I appreciate how wrong you can be in your judgment.”

Checking racial boxes is a dubious strategy regardless of one’s intentions, but perhaps it’s worth noting that the Mets at the time were trying to develop an outfield featuring Cleon Jones [19], Tommie Agee [20] and Amos Otis [21] (three Mets from Mobile), saw Ed Charles [22] as their spiritual on-field leader and had just traded for Donn Clendenon [23].

Still, Murphy hadn’t run the Mets when they selected Chilcott — that was still George Weiss’s department. Weiss’s Yankee tenure wasn’t one of the more glorious periods of baseball integration, to say the least, and a number of black players of that era heard rumblings that they’d been traded or passed over because they dared to date across interracial lines. This piece about Jackson and the Mets [24] discusses their experiences, including those of Vic Power [25], who was buried in the Yankees’ farm system under Weiss.

In later interviews and autobiographies, Jackson said the Mets’ issue was that he’d dated white women and had a Hispanic girlfriend at the time of the draft. Jackson said Bobby Winkles [26], his Arizona State manager, warned him that he wouldn’t get picked first because of that. (Winkles has denied that.)

Reggie Jackson, of course, says a lot. My suspicion is that it still eats at him that he wasn’t the top overall pick. Combine that with having had to deal with a lot of toxic shit as a young black star (and as a not so young one) and you get a narrative that’s convenient for a lot of people, starting with Jackson himself.

As for the Mets, who knows? They did have a number of promising outfielders in ’66, and a glaring hole at catcher. Yet it’s also not a stretch to think that Weiss may have looked at two amateur players rated relatively evenly and opted against the one who would attract attention — for his temper and his mouth, certainly, and perhaps also for his dating habits.

We’ll never know — it’s far too late to ask Weiss. But what bugs me is once again we’ve lost sight of the man who’s been reduced to the punch line.

Steve Chilcott didn’t turn out to be Reggie Jackson, but he was a good enough player to hit .290 as an 18-year-old in the Florida State League. He got hurt, as innumerable baseball players have before him and will after him. That’s not his fault, or the Mets’ fault. If there’s any lesson in it, it ought to be the one baseball drums into players and fans alike — that this is an unfair game, one that will drive you crazy if you let it.