Jimmy Piersall [1] and the Mets might not have been the best fit when they came together for 40 games in 1963, but no .194 hitter ever left behind a more camera-ready legacy. The story’s been told as much as any from the second season of New York Mets baseball. Piersall, who had his talents and his troubles, landed on the worst team in captivity, sent from Washington, D.C., to Washington Heights as compensation for the managerial services of beloved just-retired first baseman Gil Hodges [2]. The career American Leaguer, two-time All-Star outfielder, and subject of a major motion picture starring Anthony Perkins — following Piersall’s nervous breakdown and the book he wrote documenting it — was miscast as a member of Casey Stengel [3]’s tenth-place ensemble, but he definitely had one intensely memorable Met swing in him.

Sitting on 99 lifetime home runs for almost a month after joining the Mets on May 24, Piersall decided that when he finally moved into triple-digits, he was going to do something special to celebrate. Finally, on June 23, in the first game of a Sunday Polo Grounds doubleheader versus the Phillies, the Mets’ starting center fielder swung and connected for No. 100 off a mild-mannered (cough-cough) righty named Dallas Green [4].

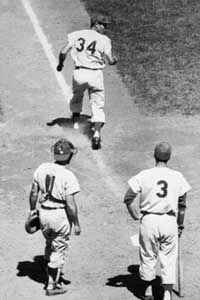

Then, once he knew it was gone, he ran the bases in a backwards motion, reversing his gait all the way from first to home. This trip was different from what anybody had ever seen in a baseball game, and it has yet to be forgotten. When it was reported on this Sunday in June, 54 years later, that Piersall had died at 87 [6], it was hard not to conjure the signature image of No. 34 approaching the plate, the runner glancing over his right shoulder to make certain he wasn’t straying from the baseline. Two other players are visible in the foreground of the photograph that survives, neither of them forming a welcoming committee. On-deck hitter Tim Harkness [7]’s body language indicates impatience (and admirable restraint in not wielding his bat ASAP). Phillies catcher Clay Dalrymple [8] is likely monitoring the actions of his batterymate, for Green did not appreciate Piersall’s brand of flair. Dallas wrote decades later in his memoir, “I was pissed off by his antics. I stalked him as he rounded the bases, swearing up a storm.”

The backpedaling bit didn’t go over huge among Metsian observers, either. In the Daily News, Dick Young labeled Piersall “a pure-beef hot dog,” and compared him to the tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Nonpareil character Stengel — who had long ago revealed a sparrow under his cap while playing big league baseball — legendarily declared there was room for only one clown on his team, and it wasn’t gonna be the guy whose NL average was trending inexorably downward. By mid-July, the former Red Sock, Indian and Senator, added Met to his ex-files. Jimmy caught on with the Los Angeles Angels (then actually of Los Angeles) and played for them until 1967, homering only four more times, rounding the bases in orthodox fashion on each occasion.

How mundane. Duke Snider [9], who had recently launched a milestone home run of his own for the very same 1963 Mets, said to the man of the counterclockwise hour, “I hit my 400th homer and all I got was the ball. You hit your 100th and go coast-to-coast.” Indeed, Piersall received national attention, a one-way ticket to Southern California and enduring…notoriety is often misused, but it seems to be the go-to word here. On a team where loads of losing was gamely tolerated, the guy who hit a home run to key an eventual 5-0 win was grimly frowned upon in real time and in most retellings.

Nevertheless, we remember it to this day and appreciate it as an element of what made the early Mets the early Mets. Nobody got killed. Nobody got hurt. Piersall’s feel for what was good fun may have gone afoul of his sport’s code of honor, yet, generally speaking, he didn’t exempt himself from his singular sense of the absurd. Or as he was known to say, “I’m crazy, and I got the papers to show it.”

At least Piersall meant to go backwards — and at least his team won the day he did so. I doubt going backwards was part of the current Mets’ plan, yet there they keep going, in the wrong direction. They’ve dropped from the periphery of contention, they’ve drifted well south of .500 and even their routine inning-ending machinations can’t properly end innings.

Posterity will tell if the signature play of Sunday, June 4, 2017, will linger in the baseball subconscious as its predecessor from Sunday, June 23, 1963, has. My guess is probably not, yet once again, the Mets did something so decidedly different from the norm that onlookers were left to wonder if anybody else had ever seen anything like it.

• First, with one out and Josh Harrison [10] on first, they turned a 5-4-3 double play to complete the top of the seventh at Citi Field.

• Then they left the field for the weekly extended-mix version of the seventh-inning stretch, the one that commences with “God Bless America,” continues with “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” and concludes with “Lazy Mary”.

• Then they prepared for the bottom of the seventh, only to be informed, no, your double play didn’t count, it’s still the top of the seventh, get your pitcher back on the mound.

Yeah, that sort of sequence doesn’t unfold very often.

Give or take a silly millimeter, this wasn’t the Mets’ fault, exactly. Well, theoretically, Neil Walker [11] could have kept a foot more convincingly planted on second base while retrieving the relay of John Jaso [12]’s grounder from third baseman Wilmer Flores [13]. As was, Walker caught the ball and threw it for an uncontested out at first. Jaso was definitely retired on the play. Harrison, meanwhile, didn’t bother running all the way from first to second; he knows what a 5-4-3 double play looks like when he’s caught in the middle of one. If replay review didn’t exist, you wouldn’t have blinked at the out call on what we used to refer to as a neighborhood play, the neighborhood in this case appearing to be comprised of attached row houses. There was virtually no space between Neil’s shoe and second base. But just as replay review exists, so did the slightest sliver of daylight when it mattered. Pirate skipper Clint Hurdle [14] thus issued a challenge to confirm that Walker’s foot was not on second base at the precise moment he took Flores’s throw, and the umpires were obliged to cooperate. Confirmation was forthcoming. Harrison was ruled safe.

In any other inning, or even on another day of the week in the same inning, such inanity would have proceeded relatively smoothly and generated no more than annoyance for transpiring at all. But Sunday being Sunday, and “God Bless America” being sacred (for if it is not sung at a ballpark, America might not get blessed), the umps felt compelled to respectfully wait to go through the motions of making it clear to everybody who might care that video officials in Chelsea were being consulted. As a result, Terry Collins, his team, the fans on hand and the folks at home were quite surprised to learn that, once the seventh-inning stretch rituals were over, the top of the seventh was to be rejoined, already in progress, with two out and pinch-runner Max Moroff [15] on second.

Naturally, it all conspired to undermine whatever was left of the Mets’ chances. Josh Edgin [16], who had thrown the nullified double play ball, immediately surrendered a run-scoring single to David Freese [17], which increased the Pirates’ lead from substantial to prohibitive. Then Edgin got the third out. Then there was another seventh-inning stretch, albeit sans “God Bless America”. Whether it’s the crew in Chelsea or the Lord in heaven, you can bother ultimate arbiters with your sincerest beseechments only so many times in one day.

Eventually, the lopsided visitor-friendly score built to an 11-1 final [18] that is rather misleading, for the contest was never that close. The defense was bad, the offense was worse and Tyler Pill [19] was no remedy for what ailed us. The only legitimate home-team highlight occurred when Collins couldn’t resist demanding his own challenge in the top of the eighth. Since the play nominally in question wasn’t remotely disputable, I assume Terry insisted the umps ask the replay officials to examine his life choices and see if the decisions that led him to manage such a lousy club on such a lousy day could possibly be reversed.

There wasn’t enough to overturn.