My Mets fandom begins with Rusty Staub.

My first Mets memory is my mother leaping up and down in our house in East Setauket, N.Y., yelping “Yay, Rusty!” Though that undersells it, actually — that moment is my first memory of anything that I can connect with an actual person or event, as opposed to one of those vague childhood impressions you suspect your brain cobbled together with an assist from old stories and photos. “Rusty, my mom, the Mets” is the earliest point I can recall in which there’s a me interacting with everything that wasn’t me.

And that’s all I recall. The heroic act that had my mom so worked up is beyond reconstruction, except for an educated guess that it happened in 1973 or 1974. The rest of the memory, I suspect, has been filled out and embellished over time. But I think I recall first being a little worried that something had caused my mother to lose her mind and start gamboling about like some crazed faun, and then keenly interested that such things existed. Whatever it was, I wanted in, because it looked like fun.

“Yay, Rusty!” Maybe I could yell that too. And so I’ve spent most of the next 45-odd years doing just that.

If you start young enough, like I did, a first favorite player can be an odd thing. I remember very little of Staub in his first go-round as a Met — nothing about his arrival in April 1972, right on the heels of Gil Hodges‘ sudden death; or about how a broken hand short-circuited his first season in orange and blue; or about his heroics in the fall of ’73; or about his becoming the first Met to crack the 100-RBI mark in ’75. I know about those things, but any firsthand accounts of them have been erased. I can’t reconstruct his batting stance from WOR broadcasts, or recall a day cheering for him at Shea, surrounded by sketchy ’70s people with mustaches and cigarettes and paper cups of bad beer.

So what do I remember?

Three things.

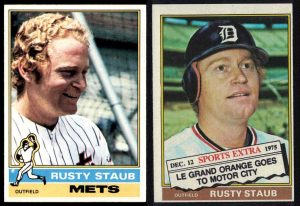

The first is Staub’s baseball card from 1976, the inaugural year I collected. (Which is why, on some level, the Mets’ colors will always register with me as Michigan maize and blue.) It’s a BHNH photo, which is Topps-speak for “big head no hat,” but a rare worthwhile one, because it showcases Staub’s famous and fabulous mane of red-gold, seemingly molten curls.

That hair fascinated me, as did the name Rusty. Kids I knew were named Mike or Melanie, Jennifer or John — or sometimes Jon, just to be confusing. I didn’t know anybody with a name as interesting as Rusty, and was intrigued by the Baseball Encyclopedia’s revelation that Staub’s real name wasn’t Rusty but Daniel Joseph Staub. By the way, Daniel Staub is a terrible baseball name, squat and pedestrian, but Rusty Staub is a wonderful baseball name, half fanciful/friendly and half brusque/no-nonsense. It really is the little things.

Anyway, the name was the second thing. How did that work? Had his parents given him the alternate name Rusty? If so, why hadn’t mine given me a wonderful parallel identity? Or — and this was where the foundations of the world really got wobbly — had Daniel Staub named himself that? Could you do that? Maybe you could, if you were brave and audacious enough — if you were a hero. Which Rusty Staub plainly was. He was my favorite Met, after all.

The third thing I remember about my favorite player was the day he was sent away, to a possibly fictional place called Detroit. That was in December 1975. I don’t remember how I found out, but I do remember shock, fury and desolation. How could this happen? How could the people who ran the Mets yet somehow weren’t Mets themselves — and there was a new and disturbing idea — be allowed to do such a terrible thing? Someone should stop them. I didn’t know if that someone was the president, or Batman, or one of my parents, but the need was glaring and obvious and the fact that the world kept on blithely turning in the face of such an injustice struck me as obscene.

I briefly declared that I was a Tigers fan, which didn’t stick — the Tigers played in some other state and in some other league, which meant they might as well have conducted their business on Mars. But I clung to Rusty’s 1976 traded card (“Le Grand Orange Goes to Motor City,” two terms that were likely mysteries to me), and then to his ’77 Tigers card, an action shot with a shouted crimson A.L. ALL STARS banner along the bottom. That shout, it was obvious to me, was directed at M. Donald Grant, the evil man who was ruining the Mets, and I imagined thrusting my well-loved ’77 Rusty into his face, after which he’d tremble and break down and apologize for exiling Rusty and then for his other crimes. Then he’d go away forever.

Rusty might have been exiled, but no one could take away my most prized possession — a Rusty Staub signature baseball mitt, with his loopy but somehow fussy autograph on the thumb. Therein lay a story. There was no signature Rusty Staub baseball mitt on the market — Staub had a contentious relationship with licensing, which is most likely why he’s MIA from the ’72 and ’73 baseball-card sets. Failed by commerce, my parents fell back on ingenuity. They bought a generic kid’s mitt and a leather-burning tool, and carefully copied Staub’s signature from one of my baseball cards. My mother was certain I’d see through the subterfuge immediately — facsimile signatures weren’t normally thin and brown and faintly redolent of burnt cowhide — but I was innocent in such matters, and none the wiser. I loved my Staub glove and used it avidly though ineptly until even I had to admit it no longer fit. Years later, when I finally found out the truth, I loved it even more.

Staub had a second go-round with the Mets, returning for the 1981 season. Unfortunately, what should have been a joyous homecoming barely registered with me. 1981 was when I fell away from the faith, my interest in baseball eroded away by the strike but also by new pursuits. I was glad Staub was back, but I couldn’t tell you anything he did in ’81, ’82 (the year for which I picked him in A Met for All Seasons is a shrug and placeholder for me) or ’83. Luckily for me, though, he was still around in 1984, when Dwight Gooden brought me back into the fold.

The Staub of ’84 and ’85 was a very different player than my childhood idol — “an athlete and a chef, he looked more like a chef,” in the words of the great Dana Brand. He was basically sessile by then, a ZIP code crammed into mid-80s Mets motley and limited to pinch-hitting. But while he had become a player who only did one thing, he did it exceedingly well. You could almost see him thinking in the on-deck circle and at the plate. Physically he was still, almost a statue in the batter’s box, but mentally he was hard at work, arranging the at-bat so that he’d get the pitch he wanted in the count he wanted. Which he usually did.

He also fed my growing hunger to understand everything that went into excellence on the field. I’d learned the basics of Staub’s life and career as a kid, putting it together from the back of baseball cards and Baseball Digest features. But in the mid-80s I began devouring behind-the-scenes books and articles, and he was a powerful presence in them as well. He was Keith Hernandez‘s superego, the man whose disappointment seemed to sting Keith where he’d brush off the reactions of others, and a self-possessed veteran who’d teach any young player wise enough to listen not only about baseball but also about life, particularly life in the big city. I learned about the book he kept on pitchers, his almost supernatural ability to detect their tells, and that he shared his insights not indiscriminately but with players he thought had earned them.

Staub retired at the end of ’85, and for me the fly in the ointment of 1986 was that he wasn’t there to get a ring as a World Champion — if baseball had stayed with 25-man rosters, would that last roster spot have been Rusty’s? But though he’d retired, he never really went away. He was a Mets color guy for a time, and honesty compels me to observe that as a broadcaster he was a helluva ballplayer. After that he was an éminence grise — or, properly, an éminence orange — showing up now and again for broadcasts and stadium events.

I was old enough now to appreciate the sweep and scope of an extraordinary career and life. Staub debuted with Houston in ’63 as a 19-year-old, but he’d been a Colt .45 before the team ever played a game, drafted in the fall of 1961. He’d collected 500 hits for four different clubs — the Astros, Expos, Mets and Tigers. (Plus 102 for the Rangers, for 2,716 in all.) He was the second player to hit a home run before he was 20 and after he was 40, joining fellow Tiger Ty Cobb. (Gary Sheffield and Alex Rodriguez would later join their club.) He almost singlehandedly won the ’73 NLCS for the Mets, hitting three homers in four games, helping calm a bloodthirsty Shea crowd that wanted to murder Pete Rose, and making a superb catch while smashing into the outfield wall. That collision wrecked his shoulder, leaving him unable to throw; somehow he still hit .423 in the World Series.

And he was just as interesting off the field. He’d been an activist for himself and for players in general before the Messersmith-McNally decision, with his outspokenness and daunting intelligence precipitating his departure from the Astros years before it led to his trade from the Mets. Traded to the Expos (another team yet to play a game), Staub found himself frustrated that he couldn’t understand young fans who addressed him in French. So he learned the language, an effort that made him beloved in Montreal. And he loved Montreal back, embracing the city’s culture and love of wine and food. He loved New York with similar fervor, opening restaurants and starting charities, raising millions for food banks and children of police officers and firefighters who’d died in the line of duty.

Rusty also kept popping up in my day-to-day life. In September 2004 I ran the Tunnel to Towers race through the Battery Tunnel to the World Trade Center site, and perked up before the race when I realized Staub was one of the dignitaries called on to say a few words. Afterwards, I spotted a familiar figure walking by himself down West Street. Was that really him? It really was. I froze, then got up my courage and ambled over to him, only to discover I was more nervous than I’d realized. Rusty, no fool, never broke stride as I peppered him with inanities. When I finally managed to say what I should have said in the first place — that he’d been my favorite player as a kid and I’d just had to tell him that — he thanked me and said that meant a lot.

I immediately regretted not telling him the story about the glove, and so was surprised and delighted to catch sight of him a few months later in the San Francisco airport. This was my chance! Before I could close to “Hey Rusty!” range, though, he sensed danger and made a neat sidestep into the men’s room. That was enough to check my enthusiasm; I decided to let Rusty be.

And so I did. He kept popping up anyway — a couple of months after that I was in New Orleans and wound up riding to the airport with a cabbie who’d played high-school ball against him and his brother Chuck, and regaled me with stories about both of them. (One more Rusty factoid: Ted Williams flew down to New Orleans to recruit him personally.) I gave the cabbie a ludicrously large tip, pleased by yet another Rusty encounter, even if this one was once removed.

Staub died on March 29, 2018, and at first it seemed incomprehensible that my first favorite player could be gone — and on Opening Day, no less. But in mourning his death, I realized that through sheer dumb good fortune, my first favorite had been a perfect choice. He’d been a Met when I was a child who just wanted to hoot and cheer, one who came with a cardback full of interesting factoids to memorize and recite. He’d returned to the Mets when I was a teenager fascinated by the mental aspect of baseball and its hidden workings. And he’d stuck around as an alumnus when I was an adult curious about interesting lives and currents in the game’s history. He was gone, tragically, but he’d never be forgotten, not by me. How could he be? After all, he’d been there from the beginning.

Read more A Met for All Seasons posts.

Good memories. Rusty was the best. A true Mets hero. I remember hunting for a glove with his signature and being disappointed that none existed. That prompted studying your Staub baseball card and then forging and burning his signature onto the new glove (a birthday present I think). So glad you were fooled for a bit, and so glad it was a small contribution to your love of the game.

You are the best, Mrs. Fry!

Can confirm.

I remember the winter after he was traded, manager Joe Torre came to town and was asked about the trade. Torre said something about how Rusty was a tough negotiator and they wanted to trade him before he reached 10-and-5 status, but you could see in Torre’s expression that he knew this was a pretty lame excuse for trading your best batter.

One of the first Mets to hit my consciousness as well. I remember older kids talking about this amazing ballplayer named “Rusty Star”. (Now there’s a great baseball name!) I remember the trade happening – Staub-for-Lolich is underrated in the Worst Met Trade of All Time contest. And then his return to be possibly the best pinch hitter in Mets history. I remember a game (I think in ’84?) where the Mets were short on players and Davey was forced to play Rusty in the outfield. Someone hit a gapper, and watching Rusty running flat out and tracking it down was probably a lot more fun to watch than it was for him to do. And yeah, it would have been nice for him to be there in ’86, although his absence allowed another one of my faves, Lee Mazzilli, to return in that role.

Mickey Lolich was the first ballplayer I truly hated*. I distinctly remember lying on my bed fighting back tears as a ten-year-old when Rusty was killing it for the Tigers and Lolich was a fat slob disinterestedly floundering around Shea.

This also got me started early on hating M. Donald Grant. Interestingly, at a talk Rusty gave at the 2013 All-Star Fanfest, Rusty said he actually reconciled and became friends (and drinking buddies) with Grant. He said one day at a bar Grant said “Why the hell did I ever trade you?!”

*I’m a little foggy on the date. I may have hated Tito Fuentes earlier. He had a fight with Bud Harrelson that did NOT sit well with me. I’m pretty sure I still have a Fuentes Topps card defaced with childish insults like BIG JERK.

I was too young for the Pete Rose hatred of ’73.

Loved Rusty Staub, and miss him very much. I donated to his Policeman’s and Firefighter’s Widows Fund, which he generously created after 9/11. Funny that you mention you dont remember how or when he became a Met. I became a fan in 1973, and Felix Millan was my favorite player. However, I do not remember when they acquired him, and only learned later on that 1973 was his first season with the Mets. And how surprised I was thst he played AGAINST the Mets in the playoffs in 1969.

I can personally attest to the fact that he did not like to sign, as I used to hang out outside the Diamond Club waiting for autographs as the cars pulled into the lot outside Gate C. He would not sign, but said he would talk, and he was wonderful.

Great song by Terry Cashman. We Remember Rusty, and always will.

Hey DAK, I guess it was 1975 when Tito Fuentes got into a fight with Mike Vail at Second Base. Vail was on Kiner’s Korner that night, and Ralph said he was going to buy him some boxing lessons.

Eric – wow, you’re right! It’s been so long.

Your Staub experience essentially mirrors mine. I latched on to Ken Singleton earlier, and then Rusty afterwards. I remember being slightly puzzled at Singleton’s absence, but not overly concerned because. . .Rusty. He and Seaver were my guys. The Lolich trade was the first dagger ever in my young Mets-ian heart-good, but not adequate prep for the Seaver trade. Yet, I still came back, and still remain. Thank you for this great piece during this unprecedented time. Hope all is well with you and yours, Greg’s and his- actually everyone heres loved ones.

saw him throw out tito fuentes at first on a short single , he charged the ball and nailed him..