Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

You’ll never know the pleasure of writing a graceful sentence or having an original thought.

—Aaron Altman attempting to verbally torment a trio of toughs after his high school graduation, Broadcast News

I want to say that the first time I remember encountering the word “literati” was in a story that referenced Peter Gent, author of North Dallas Forty. The conceit was that Gent would come into Manhattan with the Dallas Cowboys in the days when their dates with the Giants awaited at Yankee Stadium and attend kickoff-eve cocktail parties where the football player would make highbrow book editor-types swoon primarily by being a jock who spoke in complete, complex sentences. In the article I’m sure I read yet can find no evidence of despite myriad searches combining “literati,” “Peter Gent” and “cocktail,” there was much backslapping on the Paper Lion circuit when it was learned that this sui generis receiver had been traded to the Giants and would therefore be accessible all autumn long to talk pigskin and existence in terms that went beyond hut-one, hut-two.

Alas, articulate Gent was waived by the Giants as training camp ended. Never a star in the NFL, he didn’t become truly famous until the publication, several years after his retirement, of North Dallas Forty, a novel that told a real story about life in professional football. Maybe he was a cocktail party secret in the ’60s before going big-time in the ’70s (so secret that even Tom Landry must not have realized his player was out and about). Or perhaps I’m confusing something I read in the book written by Gent with something I read in a magazine about Gent. Or Dan Jenkins wrote something similar somewhere about somebody else, actual or fictional, given that Semi-Tough and North Dallas Forty were published around the same time and I got around to reading them around the same time. Or am I conflating these cultural touchstones with that episode of The Odd Couple in which Oscar owes the owner of a football team from Texas (tycoon Billy Joe, portrayed by Pernell Roberts) a large sum from poker losses and, because this is The Odd Couple, Oscar settles up by convincing Felix to let his band the Sophisticados perform at a hoedown, albeit as Red River Unger and the Saddle Sores?

Whatever the hell it is I’m thinking of, the image returned to my consciousness right around this time of year — it’s late May, in case you’ve lost track — ten years ago. That was when R.A. Dickey was called up from what we used to know as the minor leagues and introduced himself to all who love the Mets, but sent out a subtle dog whistle to those of us who not only cherish the Mets but relish the English language. If our little subset had been indulging in a Gent-eel soirée, we’d have all set down our martini glasses and focused our attention at game’s end like a laser on what the stranger from somewhere South of Staten Island was saying on SNY.

Then we’d have each lunged for the nearest Thesaurus to craft a phrase less hackneyed than “like a laser”.

I doubt Dickey knew he was doing it. That’s what made him all the more rootable. He was just being himself — and in the process of evincing authenticity, he was endearing himself to everybody who’d gone after the verbal portion of the SATs with relative gusto while dreading the math portion. R.A. Dickey is to Mets baseball as [blank] is to [other blank]… There is no obvious answer or exact analogy. Rather than sweat a response, better you should fill in your name, settle for however many points a legible signature nets you, and ditch the test in time for first pitch Saturday afternoon. Besides, for as much as aptitude as he demonstrated by throwing a singular knuckleball between his unheralded arrival as a 35-year-old reclamation project in 2010 and the All-Star zenith of his Met tenure in 2012, there was nothing standardized about R.A. Dickey.

It’s been a decade since his Met debut, yet it hasn’t been so long since we tingled to the innings when R.A. baffled batters and the minutes when he described the process. He used words like “anomaly” and “propensity” and “compulsion” and “gingerly”. When he pitched well enough to win, he was satisfied his work “yielded this ripe a fruit”. His best pitch had to be “trustworthy”; it got better via “little mechanical nuances”; one swing could change “the culture of what’s going on in the moment”. The extra-large mitt he lugged from organization to organization so his next catcher could hope to handle his knuckleball? “This glove has a personality of its own.”

And that was just R.A. talking through his first season as a Met. Dickey didn’t have me so much at “hello” as “inconsequential.” That was the word Dickey chose to describe an atmospheric factor a beat writer asked him about after he’d lost a close one to Tim Lincecum in San Francisco. Did the wind play a role?

“Inconsequential,” he said. Swoon! Give Jon Niese a hundred hard-luck starts, he’d never come up with “inconsequential” (nor resist the opportunity to cop an alibi). It wasn’t the first time Dickey speaking about his pitching had gotten my attention, but there was something about casually tossing off five suitable syllables where nobody would have blinked twice at “nah” placed me in his corner forevermore.

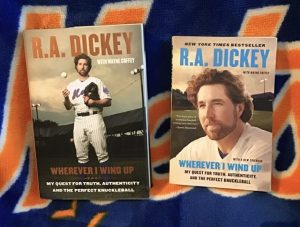

The pitching didn’t hurt, either. The pitching was key, actually. The grandest vocabulary in the clubhouse doesn’t say diddly if it comes attached to an ERA over six. English Lit major Dickey and that hard knuckleball only he threw landed like a knuckle sandwich in the face of National League hitters who hadn’t seen anything like it cross a plate near them. R.A. had it going on when he emerged from the exurbs of nowhere in 2010; when he enhanced his knuckler’s strengths in 2011; and, come 2012, when he pulled down twenty wins and the Cy Young. Between revelatory starts, he collaborated on a best-selling not to mention intensely compelling book, co-starred in a delightful documentary about his signature pitch and scaled one of the world’s steeper mountains.

The language-lovers among us who absorbed every step of his Metsian journey, especially his accounts and descriptions thereof, felt a thrill going up our leg, to borrow a 2008 phrase from Chris Matthews (himself more about Hardball than a knuckleball). I noticed that as much as virtually every Mets fan in creation toasted R.A.’s success warmly and effusively, it was those of us who worked closely with the language who seemed most thrilled on the man’s behalf. We intrinsically felt we had one of our own was out there on our behalf. Editors. Writers. Educators. This wasn’t just a Met excelling at pitching. This was a kindred linguistic spirit. We were in awe that somebody like this was so good at the sport we cherished even if most of us had never had any hope of playing it at any competitive level beyond the schoolyard (and even back then not that competitively).

“Dickey is too good to be true on so many different levels that you almost expect to wake up and find out that you’ve dreamed him,” Prof. Dana Brand once wrote. Dana, in case you weren’t around in the latter 2000s and earliest 2010s, was a leading light of Met lit; his two books of essays — Mets Fan and The Last Days of Shea indicate the glow from his writing remains eternal. Before dying too soon nine years ago this week, Dana led the English department at Hofstra University and was putting together the Mets’ 50th-anniversary academic conference there. That Dickey and Dana crossed temporal paths, however briefly, vouches for some kind of cosmic karma in our world.

“He has none of the pretentiousness that ballplayers sometimes have when they use ‘big words,’” Dana elaborated on the subject of the soft-spoken Tennessean. “He uses the English language with thoughtfulness and precision. I hope he’s our ace for the next ten years.”

In December of 2012, barely more than a year-and-a-half after Dana’s passing, R.A. was traded to Toronto for minor leaguers who grew up to become 2015 National League champions Noah Syndergaard and Travis d’Arnaud. The record will show this trade as a win in the annals of our ballclub. With Dickey on the back end of his career and Syndergaard’s potential blatantly apparent, the deal made extraordinary sense on paper and revealed itself as prescient in pursuit of a pennant.

Still, you miss someone like R.A. Dickey the way you miss someone like Dana Brand, men who could make words dance regardless of the status of their respective ulnar collateral ligaments. I’m sort of sorry R.A. didn’t get to pitch in a more successful Met era, but part of me doesn’t mind that much. R.A. Dickey was an era unto himself every fifth day. He gave us something we never had before during a period when we surely needed an element that surpassed the sum of our sub-.500 parts. We’d be blessed by the presence of superb pitching aces in seasons to come, just as we’d been fortunate to have benefited previously from twenty-game and Cy Young winners.

But to get to continually tell R.A. Dickey stories for three seasons…and to now and then recall suddenly many years later the joy he provided through his elite manner of pitching and his singular style of talking…well, let’s just say R.A. Dickey is to Mets baseball as nothing else ever was or ever will be.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

Dickey once said (after a game), “…the minute you get comfortable with losing and mediocrity, you are in for a downward vortex spiral into oblivion.”

So good, I had to write it down and use it the next day in a meeting.

Greg, just got your book ‘The Happiest Recap Volume 1 First Base 1962-1973’ in time for my Birthday, which is the same as Tommy John’s and Rich Hinton’s.

Sorry it took so long to get it, can’t wait to read it, and looking forward to Volume 2! Thanks!

Thanks!

One of my all-time favorite Mets. And I’m ashamed that I phrased that with such simple, rudimentary English. Doing so is unworthy of RA.

One year, the Mets yearbook had player profiles where you got to learn some stuff about each player outside of baseball, beyond the usual stats. One category was favorite music. Everybody listed something very familiar and mainstream, usually from the culture in which the player grew up…plenty of hip-hop, country, reggaeton, etc, maybe the occasional guy who raided their Dad’s album collection. Not RA. His was 20th century opera. So while his teammates were grooving to Jay-Z or Miranda Lambert or the occasional Born To Run or Led Zeppelin IV, here’s RA seeking out the definitive recordings of Einstein On The Beach or Mathis der Maler. I mean, how freaking cool is that? (again, very sub-Dickey language)

There was only one RA Dickey, and we were fortunate that he was not only a Met, but became a star as a Met.

I have to say, when you guys started this topic, Dickey was on my short list of must-haves. He’s one of those Plimptonesque players who would almost have to have been invented if he didn’t actually exist. And for a year, man could he pitch. And it should be pointed out that in his own way Noah Syndergaard is a worthy heir to Mr. Dickey. He may not have his predecessor’s impressive loquaciousness, but there’s a certain poetic…substance…to the phrase “I’ll meet you at sixty feet, six inches.” And he’s usually a fun interview to watch. Here’s hoping he’s recovering well from the TJ.

I was at the Trip the night Rickey pitched his no-hitter against David Price and the Rays.

David Wright bobbled a somewhat routine ground ball in the first and threw late, but was not charged with an error.

Dickey went on to subdue the Rays’ lineup, giving up a late run, but no more hits.

I stayed around to chant “Cy Young! Cy Young!” behind the Mets’ dugout with a few dozen other fans watching Dickey’s post game interview.

It was the most dominating Mets pitching performance I’ve witnessed live.

Trop, not Trip.

Dickey, not Rickey.

Dann you, auto-erection.

Makes fence to me.

[…] Staub 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1994: Rico Brogna 2000: Melvin Mora 2002: Al Leiter 2012: R.A. […]