Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series [1] in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I’ve sometimes imagined an incredibly simple game: Name Every Met. Get a bunch of paper, number the lines 1 through 1,091, and see how many you can fill in. Think of it as the ultimate Sporcle. Boom, here’s Tom Seaver [2]. And Mike Piazza [3]. And Pete Alonso [4]. And then, hours later, sometime after Mark Carreon [5] and Benny Ayala [6] and, I dunno, Alay Soler [7], you’d have a certain number of blank lines.

How many blank lines? I don’t know. I’ve never tried. Two hundred? Two dozen? If you sat there long beyond any sane measure of time, finally crawling away when your brain was broken, which Mets would you be missing?

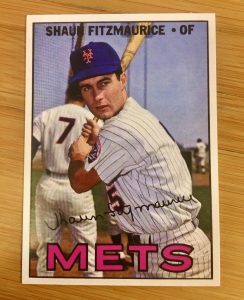

I’d probably do better at the margins than with the lesser mainstream players, because I’ve become more and more interested in the cup-of-coffee guys, the 25th men who had a week or a day or a single at-bat in the sun. That interest was always there, but it got turbocharged after I started making custom baseball cards for Mets who’d fallen between the cracks at Topps and other companies. All of those single-line Baseball Reference guys turned out to be pretty interesting stories — and lessons in how injuries, missed opportunities and plain old bad luck could mean the difference between being a trivia question and being a household name.

If you’ve heard of Shaun Fitzmaurice [8], 1966’s A Met for All Seasons (and he could only represent 1966), congratulations. Of all the momentary Mets I’ve chronicled, Fitzmaurice was the one whose failure to ignite struck me as most surpising. Notre Dame star, Olympian, cannon arm, speed and power, in the big leagues at 24, looked like a superhero … and somehow that only translated into 15 big-league plate appearances and a pair of singles.

At the top of the long list of things you probably never knew about Fitzmaurice, the name is pronounced FitzMORRIS. A star athlete at Wellesley High in Massachusetts, he graduated in ’61 and immediately got a taste of the big time, playing for the U.S. All Stars in the Hearst Sandlot Classic. The Hearst game existed for nearly two decades as an annual showcase for amateur baseball stars. The ’61 game was played at Yankee Stadium; the New York City All-Stars came away with the victory, but Fitzmaurice supplied the game’s most dramatic moment. With the U.S. All Stars down to their last out, he smashed a 400-foot inside-the-park two-run homer. The man who crossed the plate ahead of him? A kid from San Antonio named Jerry Grote [9]. Grote, by the way, was playing second base; his double-play partner was a fellow San Antonian named Davey Johnson [10].

A month later, Fitzmaurice arrived at Notre Dame. As a freshman, he couldn’t play varsity baseball. But he could play against the varsity team, and in one such game the new kid collected a home run and two doubles. As a sophomore, Fitzmaurice set school records for hits in consecutive games and triples; he also excelled at track, and was offered a scholarship, which he turned down to focus on baseball.

Between the above and that highlight from Yankee Stadium, you’ve figured out that Fitzmaurice had speed. But he also had power — as a sophomore he clubbed a 500-foot home run against Illinois Wesleyan that’s lived on in Irish lore.

Fitzmaurice finished the ’64 season as Notre Dame’s captain-elect, and was a hot commodity among big-league scouts, who looked at his combination of power and speed and wondered if they were watching the next Mickey Mantle [11].

The summer left them even more excited. Fitzmaurice played for Sturgis in South Dakota’s Basin League, another largely forgotten part of baseball lore. A semi-pro circuit, the Basin League was a showcase for players seeking to rise in big-league scouts’ estimation — during the nearly three decades of its existence, 16 future Mets played for Basin League teams.

Fitzmaurice finished as the Basin League’s MVP in ’64, hitting .361 and breaking league records for hits, total bases, triples and RBIs. But his pretty good ’64 wasn’t done. He was offered a spot on the U.S. Olympic baseball team by legendary college coach Rod Dedeaux [12]. Baseball was a demonstration sport at the ’64 Summer Olympics in Tokyo; Dedeaux’s team went 14-4-2 in touring Hawaii, Japan and Korea. The highlight was the squad’s 6-2 victory over a squad of Japanese amateur all-stars, played before 50,000 fans in Tokyo’s Meiji Stadium. Fitzmaurice was front and center, smashing the game’s first pitch for a home run and hitting .355 for the tour.

A Japanese team offered Fitzmaurice a contract, another intriguing what-if in a career that’s full of them. But he chose to play stateside and for the Mets. They beat out the Red Sox, who huffily explained that they’d been interested in the hometown kid, but he’d wanted too much money.

Instead of serving as Notre Dame’s captain, the kid who’d excelled in South Bend and Sturgis and Tokyo became a Mets minor leaguer, signing on the same day the club inked Yankee legend Yogi Berra [14] as a catcher-coach.

Fitzmaurice was billed as the center fielder of the future and was granted an invite to 1965’s spring training, where his instructors included the newly hired Jesse Owens. The legendary Olympian who’d faced down Hitler identified Fitzmaurice, Tug McGraw [15] and Al Jackson [16] as three of the club’s sprightliest runners.

Fitzmaurice didn’t set the world on fire in the minors in ’65 or ’66, but an excellent August with Jacksonville convinced the team to call him up for the last month of the ’66 season; he was recalled with a lanky young hurler named Nolan Ryan [17]. He played sporadically, often used as a pinch-runner, but collected his first big-league hit on Sept. 28, beating out a grounder to short against the Cubs. (He also showed off his arm, throwing out a runner at home.)

Though he was just 24, he had gone from prospect to suspect. Fitzmaurice would never return to the majors. He logged time in the Pirates’ and Yankees’ systems before spending four and a half seasons with the Richmond Braves. He never earned a call-up to Atlanta, and the ’73 season was his last in pro ball.

What happened? I can’t find a record of a significant injury, or some mischance that derailed Fitzmaurice’s career. He simply never ignited the way that 1964’s record of successes suggested he would. And there’s no shame in that. It’s easy to forget it, watching the best players in the world plying their trade on TV or down there on the field, but baseball’s really hard. The vast majority of “next Mickey Mantles” turn out to be the latest somebody elses, not because they’re unworthy but because the game is grueling and demanding and fickle and unfair. (And hell, even Mickey Mantle was never the player of scouts’ dreams once he destroyed his knee in a close encounter with a Yankee Stadium storm drain.)

Still, Shaun Fitzmaurice really did hit an inside-the-park homer in Yankee Stadium as a high-school player. He really did hit a first-pitch homer in the Olympic Games. He really did hit a ball halfway to the moon that they’re still talking about at Notre Dame. He really did have an amazing year during which his talent proved too big for South Bend, South Dakota and Japan. And he really did have a career that intersected those of Jerry Grote, Davey Johnson, Yogi Berra, Jesse Owens and Nolan Ryan.

All that’s pretty amazing. And a lot more than you might guess from that single line in Baseball Reference.

And hey, now you know how to pronounce his name.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962 [18]: Richie Ashburn [19]

1964 [20]: Rod Kanehl [21]

1969 [22]: Donn Clendenon [23]

1972 [24]: Gary Gentry [25]

1973 [26]: Willie Mays [27]

1977 [28]: Lenny Randle [29]

1982 [30]: Rusty Staub [31]

1991 [32]: Rich Sauveur [33]

1992 [34]: Todd Hundley [35]

1994 [36]: Rico Brogna [37]

1995: [38] Jason Isringhausen [39]

2000 [40]: Melvin Mora [41]

2002 [42]: Al Leiter [43]

2003 [44]: David Cone [45]

2008 [46]: Johan Santana [47]

2009 [48]: Angel Pagan [49]

2012 [50]: R.A. Dickey [51]