Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Didn’t we almost have it all

When love was all we had worth giving?

—Whitney Houston

As it approaches the halfway mark, the year 2020 is not making a case for itself as one we’ll wish to remember, yet it’s also one we’re not likely to forget. I’m talking about the year 2020, not the season 2020. That latter entity has yet to officially commence. When the 2020 baseball season comes along — if it comes along and plays out as currently planned — we can’t say with a shred of certainty what we as Mets fans will remember about it, or if we Mets fans as a people will remember it at all.

Some of us will, of course. Some of us don’t forget. But we tend to be the exceptions. We’re the ones who can’t believe everybody doesn’t remember what we do. We’re the ones who are incredulous that what we cherish in memory ceases to exist in the general consciousness.

Though there is no precisely analogous Metsian precedent for how the 2020 baseball season shapes up, we do have one previous year between 1962 and 2019 from which to perhaps draw a potentially predictive parallel, not so much for how well the Mets might perform in the hastily scheduled sixty-game season ahead, but for the framework at hand.

Welcome, fellow Metsian citizens of 2020, to an echo of the summer and early fall of 1981. If things had gone a little better that August and September, you might have heard about it. Things went as they did, however, and a moment that deserves to live forever in Met lore couldn’t be much more obscure.

Fortunately, the man who provided the moment lives on in Met memory. He did too much for too long to be forgotten.

No Met played in more games in the 1980s (1,116); no Met collected more hits (1,112); no Met scored more runs (592). It was his decade. The rest of us were blessed to be living in it.

A few times per season in the 1980s, generally solid Mookie Wilson — he batted between .271 and .279 five consecutive campaigns — would remind you what a spectacular player he could be. There was inevitably an inning or a game or a series or a week when he left you dazzled by his baseball brilliance. Robberies over fences. Bullets to the plate. Dashes from second to home on balls inside the infield. Four-for-fives. Triples. Steals. Streaks. Disruptions. A little roller up along first, as if one particular Saturday night/Sunday morning at-bat requires explicit acknowledgment.

And the occasional homer. It was not the personal Mookie Wilson calling card that the stolen base was (his 281 as a Met was the franchise record until Jose Reyes surpassed it in 2008), nor were there as many four-baggers (60) as three-base hits (62) on his Met ledger, but Mookie surely packed some power. He hit ten home runs in 1984 and nine apiece in 1986 and 1987. His first came off ex-Met Nino Espinosa. His last, prior to his trade to the Blue Jays, was off future Cy Young winner Doug Drabek. Wilson tagged some pretty big names along the way. Mookie was especially immune to Fernandomania, slashing .319/.380/.472 against legendary southpaw Valenzuela. Steve Carlton, T#m Gl@v!ne, Goose Gossage and Lee Smith all went to the Hall of Fame, but not before surrendering a longball to the Mets’ dynamic switch-hitting center fielder.

There was another Cooperstown-bound pitcher who felt the home run wrath of Mookie. Though breathtakingly dramatic and indisputably impactful when it happened, the encounter amounted to a hiccup for the star hurler as he continued to retire batters with regularity. The batter didn’t even mention it in his memoir, but I’m telling you, next to the ground ball Bill Buckner couldn’t pick up, it represents the most incredible swing Mookie Wilson ever produced.

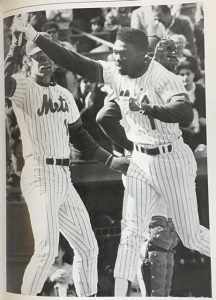

Keith was a Cardinal when that picture was taken. He might not have recognized what exactly it was from, but I can understand why he’d react undiplomatically to it.

I recognized the image for what it was: the conclusion of a walkoff home run struck by Mr. Wilson off 2006 Hall of Fame inductee Bruce Sutter on Sunday, September 20, 1981. It was very a big loss for the St. Louis Cardinals. It was an enormous victory for the New York Mets.

Wait a minute, you might be thinking. How could the 1981 Mets have an enormous victory in September? Weren’t they “el stinko”? Weren’t their seasons in the years before Mr. Hernandez became someone whose opinion we valued uniformly over by September?

Yes, mostly. But not in September of 1981. Not that Sunday afternoon.

The teams that were in first place when the strike hit on June 12 were graduated to the playoffs. The slate was cleared and cleaned as of August 10 for the resumption of play in what became the literal second season of 1981. Everybody, even the el stinko Mets of the first season, who’d been 17-34, was gonna be 0-0. Get hot for some fifty-plus games, lead your division on October 4 and you, too, could be a playoff team.

It was intriguing if not perfect. You could have the best record for a hundred-plus games total and it might get you nowhere. There was no reward for having the best record in your division in all of 1981. There was no “all of 1981” when it came to the standings. You had to finish first in one of the halves or go home. The Phillies, Dodgers, Yankees and A’s had the first half covered. The second half was up for grabs.

The Mets commenced to grabbing. The horrible start from April to June ceased to exist as a determining factor. They just had to start winning when they started playing in August and keep winning until October. They did the first part just fine. Three in a row when baseball resumed. Six and Two after eight games. Nine and Six a little over two weeks in and virtually tied for first place on August 25. The Mets were not only in a race, they were practically leading it.

Then they weren’t, which shouldn’t have been surprising given that, you know, they’d been 17-34 with roughly the same team before the strike. But it was different in September after getting a taste in late August. We who’d hung on and hung in and hung some more with these Mets futile season after futile season — last in ’77; last in ’78; last in ’79; next-to-last in ’80; and next-to-last (thanks only to the even more dreadful Cubs) in the first half of ’81 — were determined to hang on as best we could to this taste of contention, this morsel of legitimacy.

The flavor brought us to the third weekend of September and a showdown at Shea versus St. Louis. St. Louis may not have realized it was a showdown, but it was for us. They were in first place, 5½ ahead of us in fourth, with the Expos and Cubs wedged in between. There probably aren’t a lot of first-place teams psyching themselves up to take on the fourth-place team that’s barely hanging on, but that was their problem. We were showing down. We were punching up.

We beat them on Friday. We beat them on Saturday. If we beat them on Sunday, we’d be 2½ back with two weeks to go. In the Book of Amazin’, Miracle, Believe & Magic, 2½ back with two weeks to go was doable. It was the stuff of stadium graphics. We just had to get there.

The Mets lined up everybody they had to do it. They even called on Joan Payson and Casey Stengel, inducting them posthumously into the inaugural Mets Hall of Fame class prior to first pitch. Joan and Casey would have been quite familiar with what was going on after their busts made the scene. They, after all, had been around in 1962 when the Mets lost their very first game to the Cardinals. It seemed we were on our way to a similar result after Pat Zachry gave up two in the first and three in the third, with Hernandez scoring two of the five Redbird runs. The Mets were down, 5-0, fighting back but flailing in the process. Three hits in the bottom of the second for New York, yet no runs. Two hits in the bottom of the third, but still no runs. Two more hits in both the fourth and fifth…and no runs.

Not so Amazin’.

Finally, with relievers Ray Searage and former Cy Young winner Mike Marshall holding the fort, the Mets broke through in the sixth. Ron Hodges, who’d been around since “Believe” became a thing in 1973, doubled in the first Met run. Mookie doubled in another. Recently recalled Jesse Orosco kept the Cards off the board in the seventh, which gave the Mets more room to run. John Stearns, Doug Flynn and Rusty Staub (pinch-hitting for Jesse) drove in runs in succession and, Miracle of Miracles, the game was tied after seven.

Was 1981 another 1973? Another 1969? In the top of the ninth, with Neil Allen pitching, it was 1962 all over again in center field, when Wilson mishandled a Tito Landrum two-out triple poorly enough that it gave Landrum passage to an extra base and the Cardinals a 6-5 lead. “Shadows were tough and the ball stayed in the sun an extra second,” Mookie said of how September tended to play at Shea. “Once I got to the ball, I just dropped it and he kept going.” If the Cards kept going and put away the Mets in the bottom of the ninth, they’d put away the Mets for 1981.

Sutter, the premier closer of the age, came on for the save. The Cardinals traded for him in the offseason for moments just like this. The master of the split-finger fastball went about doing his job. He grounded Doug Flynn to short. He flied Alex Treviño to center. All that was left was Frank Taveras. Taveras fought off immediate demise by stroking a ball to left. It would have been good for a single, except Frankie decided it should be worth a double. Running as only he and Mookie could among the 1981 Mets (Taveras held the club’s single-season stolen base record until Wilson broke it), he took second just barely. It was simultaneously risky and gutsy, but it worked. And it brought up Wilson, who was three-for-five on the day to this point. To this point, however, wasn’t the point. Mookie vs. Sutter was.

Mookie vs. Sutter wound up being this, per Bob Murphy:

“Home run! Home run! Home run by Mookie Wilson!”

Final score: Mets 7 Cardinals 6. Twenty-two hits for the home team, who also left thirteen on base, but those LOB lads didn’t matter anymore. Just Taveras crossing the plate with the tying run, then Mookie touching it, surrounded by every Met who could make it (somebody thought to snap a picture). Hodges couldn’t make it because he’d been in the bullpen catching yet another reliever in case there were extras. Instead, he caught Mookie’s home run ball, the third of Mookie’s major league career, the first Mookie ever hit to right field.

Mookie had done it! We had done it! We were the winners of the biggest Mets game this late on a calendar since 1973. The Magic from the middle of 1980 was Back, thanks to this, The Son of Steve Henderson Game; same score, higher stakes. As dreamed and desired on Friday, we had moved to within 2½ of the Cardinals. “Today,” manager Joe Torre said of his Mets postgame, “was the first time, I think, that the fellas out there realized they were in the pennant race.” The Shea faithful didn’t need a ton of convincing. As Murph called it in the aftermath of Mookie’s home run, the stands were beset by “pandemonium”. It was “shades of old times at Shea Stadium, like the thrills of ’69 and ’73, the crowd not wanting to leave. They’re enjoying it so very, very much.”

There was no DiamondVision in 1981. There was no A/V choreography as there’d be in later years for game-winning celebrations. So the fans just took care of business themselves, sticking around and cheering in a New York groove because why wouldn’t you want a moment like Mookie had given them to last as long as it could.? “The crowd is just staying here,” Murph marveled. “They don’t want to go home. It’s unbelievable!”

Never mind that our record in the second half was now a humble 19-20. It got us into third place and within striking distance of first. The only team between us and the Cards was the ’Spos. Montreal benefited from our surge almost as much as we did, pulling to within a game-and-a-half of St. Louis.

With hindsight, they benefited more. It was the Expos, not the Mets, who kept going from September 20 forward. It was Gary Carter’s Expos, not Keith Hernandez’s Cardinals, who’d finish first. St. Loo wound up a half-game back, which was something you could be at the end of 1981. They had the combined best record when you added up the first and second halves despite not finishing first in either half. The prize for that was bupkes. Knowing that Mookie’s bullpen shot off Sutter equaled the difference between the Cardinals moving on and going home was…well, it didn’t really matter to us, because we went home, too. We’d win on Monday the Twenty-First, then not a whole lot more, quickly falling out of contention for the second-half title that would have catapulted us into the playoffs and made Mookie Wilson’s home run immortal.

Which, unless you’ve inducted it into your own Mets Hall of Fame and recognized a picture that made it to the press level facade at Shea a couple of decades later, it isn’t. Had the Mets used that weekend series against the Cardinals as a launching pad, had they refused to lose, the immortality would speak for itself and there’d probably be a documentary airing intermittently on MLB Network celebrating the achievement. The Mets of Mookie Wilson would rate that kind of enshrinement down the line, just not these Mets of Mookie Wilson, nor this swing of Mookie Wilson’s. Knowing what was to come, perhaps it’s a little greedy to wish the transcendent Mookie Wilson moment of 1981 would live on for everybody as another Mookie Wilson moment from five years hence does.

Lesson from the second season 1981 for the short season of 2020: introduce yourself to winning ASAP and remain intimately acquainted.

Got an aberrational short season ahead of you? Inexact precedent suggests you make the most of it from beginning to end.

“We didn’t come close to winning a division title in either half of the season and went home.”

It was a different assessment from the one Mookie offered after the Cardinal game. Then, when he was 25 and completing his first full season in the majors (en route to finishing seventh in NL Rookie of the Year voting, an honor nabbed by Valenzuela), Mookie said he had just played in “the most exciting game of my life. It was definitely a game to remember. I still haven’t come down. I’m as high as I could possibly be.”

Little did Mookie imagine he and the Mets could get higher, as they would as the 1980s unfolded. Most every Met Wilson played with on September 20, 1981, would be gone from Shea in a relatively short time. Mookie would stick around longer without interruption than any of them. Before Wilson was shipped to Toronto for Jeff Musselman (!) at the trade deadline in ’89, the catalyst and the team he converted would rise to elevations we would have barely fathomed in ’81. Mookie and the Mets got undeniably good in ’84; approached greatness in ’85; and, at last, defined magnificence in ’86. Mookie made just enough contact to ensure immortality for the lot of them in Game Six of the World Series. He was already beloved (ya never heard him booed, didja?). Now he was something else. We knew it as of October 25-26, 1986, and we’d remember it forever without prompting.

On September 1, 1996 — one day shy of the sixteenth anniversary of Mookie Wilson’s first game as a New York Met, the player who wore No. 1 for the bulk of a decade would become the first of the 1986 Mets inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame. It was a most apt choice.

And the Mets won that day in walkoff fashion. Also apt.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

Great piece. The 80s ended on the day they shipped Mookie off to Toronto. I was just absolutely livid. It wasn’t a logic-based reaction as much as it just felt plain wrong. Of course it’s a business and there’s little room for sentiment but I was gutted nonetheless. Jeff Musselman didn’t exactly win anyone over either.

Mookie is one of my top two favorite Mets of all time. Man he was a fun ballplayer to watch. All hustle, all team, all the time. He struck out too much, sometimes in spectacular fashion and every so often he’d have an outfield misadventure as described above, but Mookie never gave it less than his all and came up huge when it mattered most. Dude could fly too, Mookie ran the bases like he meant business. A total class act as a human being too, one of the all around nicest and most humble guys the Mets have ever had in their employ.

It’s hard to mention Mookie without mentioning the single greatest moment in the history of baseball. Aside from the absolute horror over the possibility that the Mets were going to blow their magical dream season there was the added terror of the possibility of Mookie Wilson making the last out. Of course he instantly dug himself into a hole, which the free-swinging Mookie was want to do. But it turned out there was nothing to worry about, as Mookie was up. Number One indeed.

Mookie was traded the same week Bloom County ended, and indeed it felt as if it was time to get a new decade going.

I so remember this game. An NFL Sunday and I was glued to WOR. I didn’t think anything could eclipse the euphoria of the Steve Henderson Game, but this one did. I never made the connection that the final scores were the same. Amazin’!

I also didn’t realize Keith’s Cards had the best overall NL East record that year and didn’t make the postseason. I knew about the Reds, of course, but not St. Louis. Tough break, Whitey.

Thank you, Greg, for this wonderful memory and for you and Jason helping us through these tough times. This blog provides us with a sorely needed diversion.

Thanks, Flynn. We’re glad you’re enjoying.

Sometimes, Mookie’s defense was almost as bad as Gilkey’s, especially when he got near the wall.

But he sure was a fan favorite.

I remember Bloom County ending, better than I do this game….. Sorry.

Mookie won the Mets the first game I ever saw live. (Second, technically – it was a doubleheader.) Twelfth inning, he beat out an infield single, stole second, and came home on a ground ball to the infield. Mets 1, Pirates 0. People talk about walkoffs, but Mookie was the only guy who could give you a “runoff”. If you suggested to me that Mookie was my favorite Met ever, I wouldn’t put up much of a fight.

Jeff Musselman. Now there’s a name I could have done without seeing again ever.

Things I never knew existed before reading this entry: Bloom County, Jeff Musselman, guys playing for a decade and hitting more triples than dingers.

Re: Jeff Musselman, consider yourself fortunate.

*How much* worse than Edwin Diaz-aster, 2019?

Because I still see that one game at Dodger Park unraveling live in front of my very eyes.

Bloom County began in 1980 and ended in 1989, just like Mookie’s Met career.

Amazin’

The thing about Jeff Musselman is that he’s despised not because he was a terrible pitcher (bad, but I’ve seen worse). It’s more that he was just mediocre, and he’s the guy the Mets traded Mookie Freaking Wilson for.

Let’s see if I can explain this. It’s like, imagine there was an iconic player on these Mets who’s been there forever and everyone loves, then he gets traded for, say, Jacob Rhame, or Eric Hanhold. If you’re going to trade Wilson for a bad player anyway, let him at least be bad enough to make the trade memorable. Take for example from that era, Dykstra and McDowell for Juan Samuel. Now that was cataclysmic. Musselman wasn’t even bad enough to be “worthy” to be traded for Mookie. If that makes any sense.

[…] One’s Moments in Time » […]