Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

There’s a new world comin’

And it’s just around the bend

There’s a new world comin’

This one’s comin’ to an end

—Cass Elliot

If I have one certainty as a Mets fan, it’s that no Met will ever give us a more significant career as a Met than Tom Seaver. If I have a second certainty as a Mets fan, it’s that no Met’s promotion to the big leagues will ever mean as much to the Mets and their fans as that of Darryl Strawberry, coming as it did in 1983.

As of this moment, we’ve had 402 players make their major league debut as Mets. Bob Moorhead was the first. Andres Gimenez is the most recent. Seaver was the 39th. Strawberry checked in 140th. Moorhead didn’t mean much in the scheme of things. Gimenez we can only hope. As mentioned, no Met has ever been or ever will be more significant than Seaver. But when it comes to getting our hopes up, nobody has matched or will match Strawberry.

Nobody can. We looked forward to the arrival of Darryl Strawberry from the moment we’d heard of him and it occurred to us that all we had to do to have him was draft him and sign him. That was it. It wasn’t going to take a fancy trade. It wasn’t going to take the kind of free agent commitment to which the Mets had been allergic since big-ticket stars became available for the price of money. The 1979 Mets, unbuoyed by any kind of helpful acquisition, were at least clever enough to finish with the worst record in the National League, entitling them to make the first selection in the 1980 amateur draft (the privilege of picking first alternated by league in those days). They couldn’t call it tanking. The 1979 Mets finished worst on merit.

In the spring of 1980, there was little chance for a run-of-the-mill baseball fan to form opinions on scholastic players, not like there’s been for the past couple of decades at least. Maybe one name every few years would break into the general consciousness. Forty years ago, that name was Darryl Strawberry. Once you’ve seen a name like that, you’re not likely to forget it.

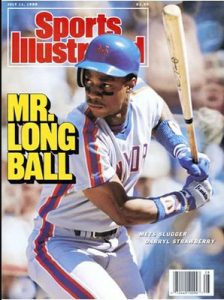

Picking up Sports Illustrated’s baseball preview issue that April, we could read about the “Stars of the ’80s” predicted to dominate the sport over the next ten years. On the cover was 1979 batting champion Keith Hernandez of the St. Louis Cardinals. He got a nice writeup alongside teammate Garry Templeton and other comers from across the NL and AL: Rick Sutcliffe of the Dodgers; Carney Lansford of the Angels; Paul Molitor of the Brewers; and Bob Horner of the Braves. The only Met mentioned among the “stars” was Nolan Ryan, in the context of not knowing which youngsters might make it big once they’d overcome their early difficulties. By 1980, Ryan was long an established superstar. He’d just been lured to Houston, becoming the first player to be paid more than a million bucks annually. You couldn’t forget that the Mets once had Nolan Ryan and traded him to California, where he’d spent eight seasons striking out most every American Leaguer he saw. You couldn’t imagine the Mets offering anybody of his ilk a multiyear megabucks contract.

In the predictions section of the magazine, the Mets were given two paragraphs of attention. They were envisioned as coming in sixth in the National League East for a fourth consecutive campaign. “Although New York should finish last again,” Larry Keith wrote, “there is hope for a brighter future, thanks to the ambitious new owners who bought the team for a record $21.1 million.” The Mets were given props for retaining Craig Swan (misspelled “Swann”) and Joel Youngblood as well as fixing up their stadium and clubhouse, but otherwise, “they haven’t substantially refurbished the lineup.” John Stearns chimed in, “Our problem is that we’ve been rebuilding for four years.” No wonder Mr. Keith finished his NL East preview with the parting shot, “while Pittsburgh is the team that everyone hopes to beat, New York is the team everyone will beat.”

That was on page 44. That was the present. But the future, if we embraced it correctly, awaited us on page 30. There, in a sidebar headlined, “Next Pick: Strawberry,” was a young man in a blue mesh ballcap and a mustard yellow top, clutching an aluminum bat. “Darryl, 18,” the caption read, “is likened to Ted Williams.”

You’re not likely to forget a comparison like that, either.

Darryl Strawberry was the one amateur player who stuck out above every other kid in the sport. You didn’t see anybody else getting folded into a package featuring Hernandez, Templeton, Molitor and so on. You did see the lede written by Joe Jares — “Darryl Strawberry may also be a star of the ’80s…” — and, if your team owned the No. 1 pick in all of baseball, you had to drool at the thought that someone who was compared to the last .400 hitter ever before you even got to the first paragraph could be ours. The brief article delved into the lefty swinger’s physical similarities to Williams, the qualities that made scouts giddy (“bat quickness”; “bat presence”; “a natural hitter”) and revealed that, oh by the way, he also pitched and excelled at a couple of other sports for Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles.

Darryl Strawberry was the one amateur player who stuck out above every other kid in the sport. You didn’t see anybody else getting folded into a package featuring Hernandez, Templeton, Molitor and so on. You did see the lede written by Joe Jares — “Darryl Strawberry may also be a star of the ’80s…” — and, if your team owned the No. 1 pick in all of baseball, you had to drool at the thought that someone who was compared to the last .400 hitter ever before you even got to the first paragraph could be ours. The brief article delved into the lefty swinger’s physical similarities to Williams, the qualities that made scouts giddy (“bat quickness”; “bat presence”; “a natural hitter”) and revealed that, oh by the way, he also pitched and excelled at a couple of other sports for Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles.

“I dream about being in the major leagues at the age of 20,” young Darryl told SI. “I dream about making it to the World Series at the age of 20 if I go to a good ballclub. And if I play well this year, I dream of coming out the No. 1 draft choice in the nation.”

Jares didn’t bother mentioning who held that No. 1 selection. Perhaps he thought injecting “the team everyone will beat” from page 44 into the idyllic scenario Strawberry was painting for himself on page 30 would be too much of a downer. But it didn’t take much for the reader, if the reader had a vested interest in accelerating the Mets’ chronic rebuilding program, to put No. 1 and this one together.

Now all it was going to take was these ambitious new owners to act appropriately.

Picking second overall the first year of the draft, in 1965, the Mets selected pitcher Les Rohr.

Picking first overall the second year of the draft, in 1966, the Mets selected catcher Steve Chilcott.

Rohr got hurt. Chilcott got hurt. Between them, they played in six major league games, all of them Rohr’s. With Seaver, Koosman and later-round draftees Ryan (10th round of 1965), Jim McAndrew (11th round of 1965) and Gary Gentry (third round of 1967), the Mets had enough young pitching to cover for Rohr’s shortfall.

Chilcott was a different story within the context of Met mythology. He’s the player drafted by the Mets ahead of Reggie Jackson. There’s more that can be said to perhaps rationalize the choice, but when you learned as a budding Mets fan in the 1970s that “they picked Steve Chilcott over Reggie Jackson,” it was “enough said”. I knew sometimes the Mets made a good choice with their first pick (Jon Matlack in 1967, Lee Mazzilli in 1973) or a decent choice with their first pick (Tim Foli, No. 1 overall in 1968), but mostly I knew they picked Steve Chilcott over Reggie Jackson.

And that they’d picked Randy Sterling with their first selection of 1969. And Rich Puig in 1971. And Richard Bengston in 1972. And Cliff Speck in 1974. By 1980, I was still waiting, to varying degrees, on the returns from the “future stars” likes of Butch Benton (1975), Tom Thurberg (1976), Wally Backman (1977) and Hubie Brooks (1978). I was definitely enthused that UCLA hot shot starter Tim Leary (a righty, like Seaver) had been picked first by us and second overall in 1979. Maybe he’d be here soon.

But I also knew that the Mets had never picked anyone like what Darryl Strawberry was supposed to be…and, from reading the papers leading up to the June 1980 draft, that they were thinking of picking somebody other than Darryl Strawberry.

A couple of years before, I asked my mother if we could get a bicycle pump. I rode a lot, she rode a lot, it seemed like a good thing to have in the house. Sure, she said, she’d go to our local bike shop, Kreitzman’s, and pick one up for us. I envisioned a regular bicycle pump, like the one that Kreitzman’s let us use when we’d wheel in a little low on air. I didn’t know how else to describe it. It was a bicycle pump.

My mother came home with something else. This, she said, was what Mr. Kreitzman said was the latest in bicycle pumps, from Japan or Europe or somewhere exotic. Having patronized Kreitzman’s for as long as I can remember, I’m sure Mr. Kreitzman was being honest. They were good people. But I gotta tell ya, the damn thing was not a bicycle pump, not in the sense that you could use it to easily inflate your bicycle tires.

“Why,” I thought to myself, “can’t we ever just get the normal thing everybody else would get?”

I thought the same thing as the 1980 draft neared. The Mets are thinking of picking somebody else? Somebody other than Darryl Strawberry? Somebody other than the next Ted Williams?

Yes, apparently they were also taken by another young man from California by the name of Billy Beane. Like Strawberry, he was an outfielder. Like Strawberry, he was said to be quite talented. Unlike Strawberry, he wasn’t Strawberry.

Jesus, ambitious new owners, don’t let us down. Please bring home the right No. 1 draft choice.

To my Chilcottian surprise, they did. On June 3, 1980, Frank Cashen, the GM Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon hired to rebuild the Mets to John Stearns’s specifications and then some, selected, with the first pick in the nation, Darryl Eugene Strawberry of Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles. Not only did they not blow it at No. 1, they got lucky later in the first round. Because they were owed compensation for losing Andy Hassler as a free agent, they got to pick at No. 23, and sitting there for the satisfaction of the internal Strawberry doubters was Beane. And, to fill out their portfolio a little more, with the first-round pick at No. 24, a product of having lost Skip Lockwood to free agency, they grabbed a catcher named John Gibbons. The draft wasn’t covered as it is today, but you heard about this first-round bounty. We got three players where it had seemed annually we got none.

Mostly we got Darryl Strawberry. He visited with the big club while they were on the West Coast later in June, meeting and posing with manager Joe Torre. He was officially signed in July and was assigned to Kingsport. Newsday sent a writer down to Tennessee to report back on his professional debut. The folks running our Appalachian League affiliate were handing out strawberries by the pint.

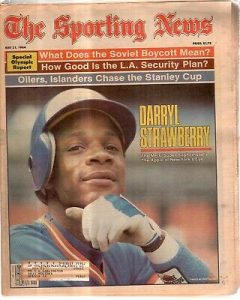

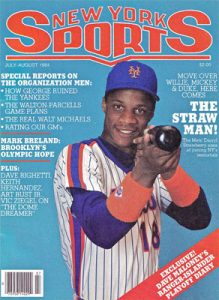

We in New York couldn’t eat up news of Strawberry’s development fast enough. From “are we gonna draft him?” we pivoted to “when is he gonna get here?” It was the summer of 1980. We understood it wasn’t going to happen immediately, and besides, we were reasonably preoccupied with the whole Magic is Back vibe permeating Flushing. But by September, the Mets had returned to “team everyone will beat” status (we finished next-to-last) and as Darryl was turning 19 in March of 1981 and 20 in March of 1982, our Strawberry yen was only intensifying. The ballclub that high school Darryl hypothesized might be good enough to add him to its World Series roster ASAP wasn’t anywhere near fruition. He might have helped a contender even then. In 1982, Darryl Strawberry of the Jackson Mets tore up the Texas League, scorching Double-A pitching for 34 home runs, 97 runs batted in and a .283 batting average. Stole 45 bases as well, because that was something he could do, too.

We in New York couldn’t eat up news of Strawberry’s development fast enough. From “are we gonna draft him?” we pivoted to “when is he gonna get here?” It was the summer of 1980. We understood it wasn’t going to happen immediately, and besides, we were reasonably preoccupied with the whole Magic is Back vibe permeating Flushing. But by September, the Mets had returned to “team everyone will beat” status (we finished next-to-last) and as Darryl was turning 19 in March of 1981 and 20 in March of 1982, our Strawberry yen was only intensifying. The ballclub that high school Darryl hypothesized might be good enough to add him to its World Series roster ASAP wasn’t anywhere near fruition. He might have helped a contender even then. In 1982, Darryl Strawberry of the Jackson Mets tore up the Texas League, scorching Double-A pitching for 34 home runs, 97 runs batted in and a .283 batting average. Stole 45 bases as well, because that was something he could do, too.

In 1982, the season after they fired the no longer Magical Torre, the New York Mets without Darryl Strawberry won 65 games and lost 97. They called him up in September, but just to give him a Doubleday Award, the prize the organization inaugurated just that year to recognize minor league achievement. A nice gesture, but we’d seen plenty of minor league achievement at Shea Stadium in 1982. And 1981. And 1980. And 1979. And 1978. And 1977. Managers changed. Owners changed. The ballpark had been painted. Swell. What we needed most was a major improvement in 1983. Darryl Strawberry was about to turn 21 and the endless rebuilding initiative was getting very, very old.

Nevertheless, trading Tom Seaver made everybody more miserable, and the cloud that moved in over Shea Stadium never fully dissipated until April 5, 1983, the day Tom Seaver returned to the mound to pitch in home pinstripes. No longer was Tom Seaver clad in Cincinnati red. This was Seaver like he oughta be. When No. 41 emerged from the right field bullpen, and close to 49,000 Mets fans stood and cheered, the Magic was as Back as it could be.

Seaver was back. In a way, the team from which he was inexcusably exiled had left a light on for him. On the 1983 Mets that Opening Day were a surprising number of survivors or at least recidivists from Seaver’s extended first term in Flushing. Ron Hodges was catching him. John Stearns might have, except he was dogged by a bad elbow. Dave Kingman was at first base. Mike Jorgensen subbed for Sky on defense. Rusty Staub was available to pinch-hit. Craig Swan was lined up to take the season’s second start, though after Tom pitched six shutout innings in the Opener en route to a 2-0 win, it almost seemed beside the point to play more games.

The paying attendance apparently thought so, for they vamoosed after Seaver gave them their dollars’ worth. No discernible crowd filed into Shea for Swan, nor veteran acquisition Mike Torrez, nor any Met starter, reliever or reserve. The 1983 Mets resisted giving their fans any impetus to pay or attend. The novelty of Seaver 2.0 had worn off quickly. The morale boost George Foster provided a year earlier didn’t even make it through 1982. Foster was still around, but he wasn’t the answer. Nobody on the roster was the answer. By May 4, the Mets, after winning their first two, had dropped to a mortifying 6-15. A three-game weeknight series against the Astros drew 15,719. That’s not an average per game. That’s the three-game gate.

It was as if 1977 had never ended. It was as if 1983 was just a continuation of every bad season in an era that was Groundhog Day before there was Groundhog Day. Something had to give. Six years and one month was long enough for the hardiest of Mets fans to wallow in the mire.

C’mon, Frank Cashen. Light our fire.

The Mets announced the promotion from Tidewater of journeyman infielder Tucker Ashford.

Oh, and outfielder Darryl Strawberry.

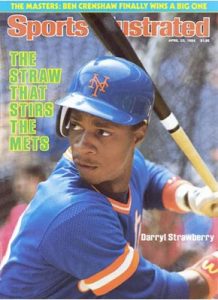

No disrespect intended to Ashford, who was called up to give the slumping Hubie Brooks a nudge at third base, but he wasn’t really the story of the transaction box that first week in May. Nor were corresponding demotions Ron Gardenhire and Mike Bishop. Darryl Strawberry, on every sentient Mets fan’s radar from the moment Sports Illustrated spotlighted him on page 30 in April of 1980, was no longer tomorrow. He was today. May 6, to be exact, the Friday night that began the Mets’ next series, against the Reds.

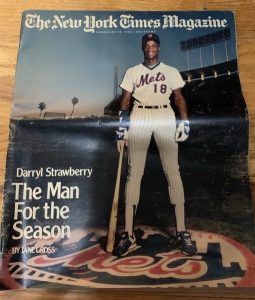

This was the second coming of Ted Williams. Also, in case that wasn’t enough of a label to hang on a 21-year-old, the second coming of Willie Mays. Mays was cited as the last Triple-A outfielder called up to a New York team with comparable attendant fanfare. I was 20 in May of 1983; I’d be 21 at the end of December. I hadn’t seen Williams play, but I had seen Mays, though toward the end of his line. Darryl, the Mets and I were all born in 1962. I rather relished the concept of the three of us ushering in a brilliant new era. My role was to watch. All Strawberry had to do was hit and hit with power and run and throw and catch everything hit to him and carry the Mets out of the morass where they’d taken up unceasing residence since I was in eighth grade and Strawberry was in ninth.

This was the second coming of Ted Williams. Also, in case that wasn’t enough of a label to hang on a 21-year-old, the second coming of Willie Mays. Mays was cited as the last Triple-A outfielder called up to a New York team with comparable attendant fanfare. I was 20 in May of 1983; I’d be 21 at the end of December. I hadn’t seen Williams play, but I had seen Mays, though toward the end of his line. Darryl, the Mets and I were all born in 1962. I rather relished the concept of the three of us ushering in a brilliant new era. My role was to watch. All Strawberry had to do was hit and hit with power and run and throw and catch everything hit to him and carry the Mets out of the morass where they’d taken up unceasing residence since I was in eighth grade and Strawberry was in ninth.

No pressure, big guy. Just be an all-time great and elevate your heretofore crummy team with you. Thanks.

I was only 20. I wouldn’t have known what to do at that stage of my life other than go to college and come back for the summer just in time to witness the debut of Darryl Strawberry. I did know this, though: I knew that for as excited as I was, I was also a little sad this was happening. I didn’t know enough about Strawberry’s ability to face breaking balls to be concerned he wasn’t thoroughly prepared for Steve Carlton or whoever. And I wasn’t aware enough to consider that just because somebody appears to be a physically imposing athlete — Darryl was listed at a lean 6’6” — that he might not be a fully realized human being. Maybe none of us is ever as mature as we should be, but I wasn’t used to thinking about ballplayers as young men except in the most basic of “this kid is supposed to be good” terms. Until May of 1983, I’d never rooted for a Met younger than me. A few days before Strawberry was promoted, the Mets brought up shortstop Jose Oquendo, born in 1963. He wasn’t just younger than me, he was younger than the Mets.

Up to this point, despite being of legal drinking age (it was 19 in those days), I had looked up to baseball players as a child might. Even the ones I derided were baseball players. I collected their pictures on cards. I taped their likenesses to my walls. They’re in the major leagues. They must know what they’re doing. How was I supposed to know that they were people? How was I supposed to know that 21, which sounded plenty old when I was 7 and 12 and 17, wasn’t that old even if the world was about to treat you as if you knew what you were doing?

I didn’t remember everything from that Sports Illustrated article that seemed like it ran in ancient times but was barely three years before. Darryl’s background didn’t necessarily lend itself to a smooth transition to stardom. Sure, he was a five-tool player, but he was benched in high school for not hustling. He was from a large family not operating in the best of circumstances. His mother, SI quoted Darryl, had been “struggling all her life”. His father wasn’t around. In later years, recounting learning of where he’d been drafted to play, he’d chuckle that he’d had no idea where New York was. Well, I knew where Los Angeles was, but it’s safe to say I had no conception of what Darryl Strawberry’s life had been. Growing up in South Central L.A., getting good at sports, then suddenly he’s in Sports Illustrated; everybody remembers his unforgettable name; he’s signed to a professional contract at all of 18 (a good one), then he’s sent to sharpen his skills in Kingsport, Tenn.; Lynchburg, Va.; Jackson, Miss.; and Norfolk, Va. And after all that culture shock, it was next stop New York City to be a savior for hordes of people he’d never met in a place that not so long before he couldn’t have pinned on a map.

Yet that’s not what made me sad or apprehensive or not 100% jubilant that Darryl Strawberry was finally, as of May 6, 1983, going to be a New York Met. What bothered me, at the ripe old age of 20, was that if the wait was over, the anticipation was over as well. All I’d done for three years — which might as well have been three decades at that age — was look forward to Darryl Strawberry. We all looked forward to Darryl Strawberry like we looked forward to no other Met before and, I assure you, haven’t looked forward to any other Met since. He was designed to change our world. On Friday night, once he trotted out to right field, and particularly once he stepped into the batter’s box to take on the heat of Mario Soto, the proving would begin.

What, I wondered to myself, would I look forward to now?

And apropos of his star quality and that name you couldn’t forget once you read it in a magazine, Darryl Strawberry, batting third (behind Tucker Ashford), encountered Soto, one of the fiercest pitchers in the National League in the bottom of the first inning and…struck out.

Tomorrow wasn’t going to come easily or immediately. But it was going to come. Tonight, as in Friday night the Sixth of May, took a while itself. Soto was mostly untouchable to every Met, no matter the level of experience. Seaver pitched for the Mets and held his other old club pretty much at bay until the seventh, but he’d leave in the eighth, trailing 3-1. The presumed dawn of a new era was heading for an anticlimax as Soto struck out Mookie Wilson to start the ninth and, after giving up a single to Wally Backman, who was pinch-hitting for Ashford, struck out Straw for the third time. Darryl was 0-for-4. The beginning was not auspicious.

But the game was not over. Dave Kingman, the reigning National League home run champ from 1982 (despite having hit .204), lived up to his crown, tying the game at three on a long homer to center. We had extras. In the bottom of the tenth, after the Reds had taken a one-run lead, we had another comeback. The hero of the moment this time was Hubie Brooks, homering and making a case for winning his job back from footnote Ashford. Finally, in the eleventh inning, the one swing everybody’d come or tuned into see. It was Darryl Strawberry, taking Tom Hume deep…and just foul.

But the game was not over. Dave Kingman, the reigning National League home run champ from 1982 (despite having hit .204), lived up to his crown, tying the game at three on a long homer to center. We had extras. In the bottom of the tenth, after the Reds had taken a one-run lead, we had another comeback. The hero of the moment this time was Hubie Brooks, homering and making a case for winning his job back from footnote Ashford. Finally, in the eleventh inning, the one swing everybody’d come or tuned into see. It was Darryl Strawberry, taking Tom Hume deep…and just foul.

So much for scripting baseball.

Darryl did reach base for the first time in the eleventh, via walk, but the Mets didn’t score. It would take until the thirteenth to resolve the issue at hand. With the 4-4 tie still in effect, Darryl was up for the sixth time in the game and his career. Two were out. The time was perfect for the next phase in the evolution of baseball superstardom — Williams to Mays to Strawberry — to manifest itself. Nah, it wasn’t gonna be that easy that quickly. But Darryl did work out another walk, off Bill Scherrer, and he did steal second. Mike Jorgensen walked next and Seaver’s fellow ex-Red Foster, facing Frank Pastore, ended the game with a three-run blast to left.

The Mets were 1-0 in the Darryl Strawberry Era.

For a while, it felt like Strawberry would never hit. Seven games into his major league career, he was a .125 batter. In his eighth game, however, he homered for the first time, off Lee Tunnell in Pittsburgh. The next night at Shea, he homered again, off a lefty, no less, Tim Lollar of the Padres. I can attest to this historical moment because I was there to bear witness. Straw homered, Seaver started, 7,550 of us were on hand for this next footstep into the future. I had to leave after six innings because of a splitting headache, but my heart was full.

The Mets would continue to lose a bunch more than they would win for a while, motivating yet another managerial switch (George Bamberger out, Frank Howard in). Darryl would continue to take baby steps. Lefties, for the most part, were trouble. He was prone to striking out — a lot. But then there’d be a day here or a day there when the fuss that followed him from Crenshaw through the minors to Shea couldn’t have been any more self-explanatory. On June 22, he took over a game right away, launching a three-run homer in the bottom of the first at Shea off Bob Forsch of the Cardinals. Tom Seaver went back to the mound in the second and turned the lead into the final complete game victory of his Mets career. On June 26, in the nightcap of the doubleheader whose opener saw Rusty Staub notch his record-tying eighth consecutive pinch-hit and me seeing it live and in person, Darryl both homered and tripled. His average was still under .200, but with me around it was gangbusters. Perhaps we were good for each other.

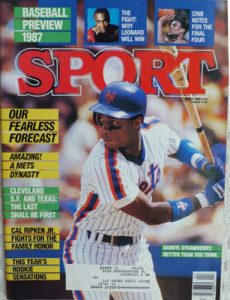

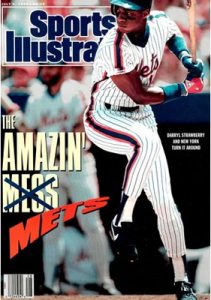

Without me in attendance very much the rest of 1983, Darryl Strawberry took off on the trajectory predicted for him when he was in high school. In his final 82 games, starting with yours truly watching him rack up multiple extra base hits from an Upper Deck box seat, Darryl batted .295, with 22 home runs and 57 runs batted in while stealing a dozen bases. Double that for a full season and you decided his success was inevitable. Eventually he played against all kinds of pitching and destroyed the bulk of it, establishing a franchise standard for homers by a first-year player (26) that would stand for 36 years.

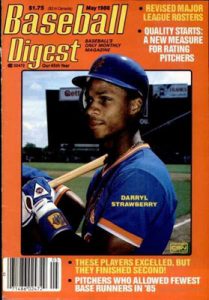

Despite not coming up until the second month of the season and not getting untracked until practically the midway point, Straw towered over the National League freshman class the way he did all of America’s amateurs three years earlier. When the ballots were cast for NL Rookie of the Year, he left the likes of Craig McMurtry and Greg Brock in the dust. The Mets had their first first-year award winner since their 1967 No. 1 pick Jon Matlack in 1972. Matlack had been the best first-round pick the Mets had ever made until Strawberry.

By the end of 1983, measuring the Mets in the context of before and after Darryl Strawberry seemed appropriate.

Center fielder Mookie Wilson continued to run the bases with alacrity. Hubie Brooks wrested control of third base back from Tucker Ashford. Left fielder George Foster reverted to a semblance of the slugger he’d been in Cincinnati. At short, Jose Oquendo was young and full of promise. Maybe not as much promise as Straw, but that was a tall order. This was a lineup coming together, supported by a bullpen to seal their handiwork. Lefty Carlos Diaz, righty Doug Sisk and especially closer Jesse Orosco were lights out. Walt Terrell, one of two righties obtained from Texas for Lee Mazzilli in 1982, made strides (he even hit two homers in one game), and the other, Ron Darling, came up in September. Darling, like Straw, had been a first-rounder.

The Mets were a last-place team again in 1983. That 6-15 start didn’t shake off so easily; they were 37-65 before truly getting it in gear to finish 68-94…which isn’t much of a record. And the attendance was still pretty light. But if you’d stuck with the Mets in the years before they earned the right to draft Darryl Strawberry, then after the clock officially started on the wait for Darryl Strawberry to rise to the majors, you knew this last-place finish was nothing like the cellar-dwelling that had been the rule of the house prior to 1983.

The future heralded by Darryl Strawberry had commenced in earnest. And, oh, what a future it would be.

In real time, it was pretty close to that. You got so used to it that you might not have noticed how immense it truly was. In the day-to-day thicket of baseball fandom, you get caught up in shortcomings. When will Keith come out of his slump? Why can’t Gary throw out baserunners like he did for Montreal? Should I be concerned that Doc isn’t striking out as many batters as he was last year? You almost didn’t notice how amazing it was to have these characters linked tightly in the cause you considered holy.

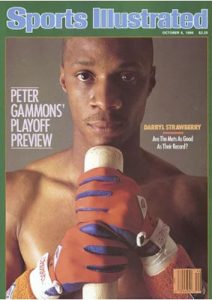

After 1983, despite his rapid ascent to the upper tier of baseball superstardom, you inevitably dwelled on what was perceived as wrong with Darryl Strawberry more than you did on appreciating all that was right. Darryl didn’t make the All-Star team as a rookie. But he made it every year for the next seven years, elected as a starter six times. He matched or bettered his rookie home run total of 26 every one of those years. Three times he hit close to forty home runs. One year he stole more than 30 bases and hit more than 30 homers.

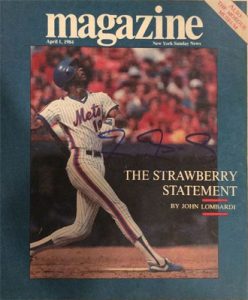

From 1983 to 1990, Darryl Strawberry totaled 252 home runs as a New York Met. It remains the most in franchise history. David Wright pulled up lame in his pursuit of this one club record he couldn’t quite reach, falling ten home runs short. Of the 252, plus the four he delivered in two postseasons, all but a handful are still going. Darryl hit the longest, most majestic home runs you’d ever seen. About half of them gave the talented Met pitching staff a first-inning lead, I’m fairly certain. About a quarter are the kinds you bring up to raise each other’s spirits decades after the fact. Nearly every one after 1983 was walloped in pursuit of a division title or higher. He hit stadium clocks. He hit stadium roofs. He disrupted Championship Series and World Series. He didn’t make it to the World Series at the age of 20. He had to wait until he was 24.

But he got there, and he got us there. Yes, all we could have wanted from that Sports Illustrated article and that wise decision regarding what to do with the first selection in the nation had come to pass. Darryl didn’t do it alone. He had high-profile help. He had Keith and Gary and Dwight. He had Mookie and Ronnie and Jesse. The cast is amazing to consider. Leading men were everywhere. The supporting players were star-caliber.

The rebuild really happened. It was barely a month from Seaver’s Opening Day turn to Darryl’s debut. While the Mets were still partially defined by Mets from the 1970s, little did we know that the present roster was a quarter-filled, too, by players who’d be around Shea in October of 1986. Little would have we dared to guess Shea would be open for business that late in a year that was coming so soon. We might have been confident coming out of 1983, but could we have seen a contender emerging in 1984, a push to the finish line in 1985 or every damn marble in creation becoming ours in 1986?

Although Orosco, Wilson, Backman, Sisk and Danny Heep were already on the team, it was the presence of Darryl Strawberry on May 6, 1983, that genuinely marked the beginning of the enormous transformation we’d all craved forever. He wasn’t the first of the 1986 Mets to arrive at Shea, but he was the first of the Big Four. We never called them the Big Four but that’s what they were: Strawberry, Hernandez, Gooden, Carter. They were all together in one place, every night pretty much, especially the nights Gooden pitched. Throw in the high-profile supporting cast and “wow,” I say to myself when I catch highlights from that era. This was our team on a going basis.

On May 6, 1983, we weren’t thinking about Hernandez in St. Louis, Gooden in Lynchburg or Carter in Montreal. We were bracing for Strawberry at Shea. He was the first to get here. He was the harbinger of our fondest dreams exhibiting themselves in the standings. He was Darryl Strawberry of the New York Mets.

Somehow, it seems to me, we too often lost sight of what the kid from Crenshaw was actually doing and how he could tower over the entire astounding scene that became Mets baseball at its best in the 1980s. We harped instead on what Darryl Strawberry didn’t do. We harped that he wasn’t Ted Williams or Willie Mays. We harped that he looked a little disinterested out in right, that some grounders didn’t get dutifully run out, that he could mope inconsolably or absent himself or snarl at a teammate or answer a reporter with an instantly incendiary reply that made you wonder what the hell he was thinking. One of the touchstone incidents everybody remembers, Darryl and Keith mixing it up on photo day in Port St. Lucie in 1989, yielded one of the great lines of the age: Darryl Strawberry finally hit the cutoff man.

Somehow, it seems to me, we too often lost sight of what the kid from Crenshaw was actually doing and how he could tower over the entire astounding scene that became Mets baseball at its best in the 1980s. We harped instead on what Darryl Strawberry didn’t do. We harped that he wasn’t Ted Williams or Willie Mays. We harped that he looked a little disinterested out in right, that some grounders didn’t get dutifully run out, that he could mope inconsolably or absent himself or snarl at a teammate or answer a reporter with an instantly incendiary reply that made you wonder what the hell he was thinking. One of the touchstone incidents everybody remembers, Darryl and Keith mixing it up on photo day in Port St. Lucie in 1989, yielded one of the great lines of the age: Darryl Strawberry finally hit the cutoff man.

Maybe it was as true as it was funny. But, really, that’s what you took away from Straw as he entered his sixth season as, by then, the best position player the Mets ever brought up through their farm system? I was going to say “…who the Mets ever developed,” but maybe that’s giving them too much credit. Every player needs coaching and mentoring, but at the end of the day and the end of a decade, it’s the player who did incredible things.

It didn’t get more incredible than Darryl Strawberry from the night he said hello in 1983 to the day he said goodbye in 1990. It could get complicated and complex and, yes, it could get frustrating. We wanted him to yield only good news, and he couldn’t. We wanted him to stick around, and he didn’t. We wanted his final stop to be Cooperstown, and that wasn’t destined to be his destination. Instead, we merely got a player who could do it all and often did.

We got the player we waited for, the player I looked forward to. Of that I am convinced.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

Wonderful trip down 1983 and prior Memory Lane. Thank you!

Just for the heck of it, although I know it’s not actually a word (or, to paraphrase a Ray Romano joke..it is now.) I looked up “Chilcottian”. The best Google could do it that there are a few people out there named Ian Chilcott, one of whom works for a British outfit called STRAWBERRY FIELDS PENRYN MANAGEMENT COMPANY LIMITED.

It’s a small Chilcottian World, I am happy to be a part of it.

Fun place, right?

I’ll never forget how strange it felt when I realized I was older than the College Football players. I mean (as Alonso always says), these guys were athletes, and really big, and how could I be older than them.

And let us never forget those mid-80s Mets, the most underachieving team of all time. We were better than the Cubs, Cards, and Dodgers, and ….. Poof!

The perennial Brave playoff teams of the 21st century who’ve never made a World Series would like a word with you.

Ah, right you are!

Before my time. Pre this read, I was aware that he was good and a Mets star. After this article, I truly understand

So glad to know an article like this not only brings a time back for those who were around but creates it anew for those not on hand back then.

Darryl was definitely “the Straw that stirred the Mets”, and his homers were the stuff of legend. (I can still hear Bob Murphy shouting, “He hit the roof!”) Still, I can’t help but feeling disappointed that he and Doc didn’t ride their magnificent talents all the way to Cooperstown. I’m not one to judge, and I know that the “bad news” that you alluded to in your post isn’t the type of stuff that one can always control. And I’m not ungrateful for the great moments they gave us, October ’86 in particular. Still feel kind of wistful for what could have been.

“More” is always appetizing when it comes to success.

[…] Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1983: Darryl Strawberry 1990: Gregg Jefferies 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1994: Rico Brogna […]