Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I’ve long had a soft spot for marginal Mets, the September call-ups and emergency starters you struggle to remember by season’s end, let alone years later. Part of that is because I love the nooks and crannies of team history. But it’s also because I suspect the gaps between 25th men, regulars and immortals aren’t as wide as we might think. Young players can get derailed by injuries, misfortune, bad timing, or any number of things, pinching off their chances to become what they might have been. What would have happened if Jacob deGrom had had an additional stumble or two as a converted shortstop in the low minors? If Mike Piazza hadn’t had Tommy Lasorda insisting he actually get a chance to prove he could play? Willie Mays started his career 0-for 12 and then 1-for 26 — what if that lone home run had been a long flyout instead?

The truly marginal Mets include the likes of Kenny Greer, whose only appearance came in the 17th inning of a Mets-Giants game at the end of the horrific 1993 season. Greer got the win, possibly the victory seen by the fewest people in team history. There’s Francisco Estrada, whose Mets career consisted of four innings in the first game of a September 1971 doubleheader against the Expos. Estrada is mildly famous for having been part of the Ryan-Fregosi trade, as an “and the Angeles also got these guys!” addendum to the punchline; he should be more famous for being a Mexican League legend whose career actually spanned more seasons than that of the Ryan Express. There’s Kevin Morgan, brought up from Double-A for a June 15, 1997 thank-you before taking a job with the team’s minor-league operations. Or Dave Liddell, called up to meet the Mets at Veterans Stadium on June 3, 1990 when Orlando Mercado went on the bereavement list. Liddell pinch-hit in the eighth, hit the only pitch he’d ever see up the middle for a single, scored nine pitches later on a wild pitch, caught the bottom of the eighth and that was it. If you went out to pick up a pizza, you missed his career.

But there are Mets even further out in the icy reaches of memory’s solar system, Mets who never even officially got to be Mets. I’ve long been obsessed with the “ghosts” in team history. A ghost, for the uninitiated, is a player who was on the Mets’ active roster and eligible to enter a game but never did. This melancholy fraternity numbers nine: Jim Bibby (a ghost in 1969 and then again in 1971), Randy Bobb (1970), Billy Cotton (1972), Jerry Moses (1975), Terrel Hansen (1992), Mac Suzuki (1999), Anderson Garcia (2006), Ruddy Lugo (2008) and Al Reyes (also 2008).

Seven of those guys played for other big-league teams, making their Met non-tenures curiosities instead of trageies. But Cotton and Hansen never did — their chance to be a big leaguer came and went in orange and blue. There’s a rumor that Cotton was on deck to pinch-hit and lost his chance when the batter hit into a double play, and I’ve gone so far as to scour play-by-play accounts of the ’72 season in search of situations that might support this story. The evidence is ambiguous; I hope that’s a tale that grew in the telling, because what happened to Cotton is cruel enough as it is.

Two spectral curiosities: Matt Reynolds began his career as a postseason ghost, activated after Ruben Tejada‘s mauling in 2015 but never getting into a game. If he had played in the postseason but never appeared in a regular-season game, he would have joined onetime Mets minor-leaguer Mark Kiger as the only player to do so. Reynolds made the point moot when he started at third in May 2016.

Then there was the curious case of George Charles Baumann IV, mercifully known as Buddy. The Padres designated Baumann for assignment in April 2018 after he lasted a third of an inning at Coors Field, giving up five runs and getting into a brawl, for which he was suspended. The Mets signed him and called him up for a Friday-night game in May, aware that they couldn’t use him that night because he had to serve his suspension. But then Saturday was a rainout, and Baumann was sent down before Sunday’s game. Ghost, or no? He was on the active roster, indicating ghost, but there was no way he could have played, indicating … well, I’m not sure what. I’m happy to say I never needed a ruling; Baumann got called back up a couple of days later and promptly gave up three runs in two innings against the Blue Jays.

Which brings us to the curious case of Joe Hietpas.

Hietpas was called up in mid-September 2004, which was a strange time in Mets history. Art Howe had been fired but agreed to finish the season, which seemed pointless from the perspective of employer and employee alike. Hietpas was a catcher known for his receiving skills and a rifle arm, though he’d never hit in the minors. Somehow Hietpas hurt himself despite having nothing to do; updates on his status were perhaps understandably scanty. All I knew was the remaining games on the schedule were dwindling with no sign of Hietpas in a box score. Howe might not have lit up a room as promised, but he was universally hailed as a genuinely nice man; surely he wouldn’t let Hietpas’s opportunity pass him by.

But the Mets’ season came down to one game, an Oct. 3 matinee at Shea against the Expos — who were themselves about to be extinct, snuffed out by the shameless Bud Selig and his contraction shenanigans. I was in the stands with Greg and two friends of his, and I remember that our neighbors included a surprising number of Expos rooters in tricolor hats. Without exception, they were treated with sympathy and kindness — they were seeing the curtain come down on their team, in the same ballpark and against the same opponent where that team had begun its life back in 1969. It was a vigil and a funeral and a protest all at once, and I couldn’t help wondering how I would have reacted, if our situations were reversed. I was pretty sure I would have gone wherever the Mets went, decked from head to toe in blue and orange and trying to memorize each and every pitch — and praying that somehow there’d never be a final out. That was possible, right? A team could keep getting hits and walks and getting on base and so keep annihilation at bay, playing on and on in defiance of its executioners, until common decency and an international outcry forced a different ending to be found.

(There was an odd coda to the Expos’ finale, by the way: Brad Wilkerson took part in an MLB tour of Japan after the 2004 season, making him the final man to wear a non-throwback Expos uniform in competition. Surely there was some diehard out there who figured out how to find those games in a dark corner of the Internet, refusing to abandon his or her post as the last Expo played on the other side of the world.)

The final game in Expos history unfolded as final games do — slowly at first and then too quickly. In the sixth, Todd Zeile — who was retiring, and had returned to his original position of catcher as a farewell — hit a three-run homer in what would be his final at-bat; in the eighth, John Franco faced two batters in what would be his final appearance as a Met. (The first batter singled, marking my last opportunity to grumble at Franco, but the next guy, future Met malpractice victim Ryan Church, fouled out to Zeile.)

I’d been mildly tickled by Zeile returning to catcher, but the novelty had worn off and I was now more concerned with a first than a last: The Mets were up 7-1, so Hietpas was rapidly running out of time. When forgettable catcher Wilson Delgado pinch-hit for Franco, I groaned. Seriously, Art? You’re a good man. Depart with a final good deed. Delgado singled home a run; I was annoyed anyway.

The top of the ninth, in all likelihood the final inning in Expos history, began with an announcement — Bartolome Fortunato was now pitching. And now catching … yes, it really was him. Joe Hietpas had arrived.

You couldn’t see him — the mask and the late-afternoon shadows took care of that. (Honestly, it could have been anyone back there.) But I took it on faith.

The inning began with an Expo reaching on an error and another Expo getting on base via a walk. But Fortunato struck out the next two guys, and Endy Chavez hit a 3-2 pitch — the 24th thrown to Joe Hietpas in the big leagues — to Jose Reyes at short. The season was over, and the Expos were no more.

Hietpas — the Mets’ own Moonlight Graham — would be back in Double-A for 2005, and hit .216. He was no more of an offensive force the next season, but he did discover a new skill, hitting 93 in a stint as pitcher of last resort. The next season, he sought to extend his career by becoming a pitcher full-time — one whose repertoire included a knuckleball, because at that point why not?

Hietpas logged a 2.47 ERA for St. Lucie in 2007, and I let myself imagine him becoming a star reliever, or maybe, slightly less unrealistically, a useful specialist. Perhaps he’d even finally get that first plate appearance somewhere along the way. Hietpas pitched in Double-A in 2008, but this time his ERA was 6.34. Thus ended the dream, and Hietpas’s career.

But he was no ghost — no ectoplasmic asterisk with an unhappy sequel. Hietpas may not have ever wielded a bat in big-league anger, but he’s in Baseball Reference — the 16,208th player in MLB history, no less. Sure, his big-league career was only eight or nine minutes, but it counted. On a day full of endings, Hietpas experienced his own ending. But he had a beginning too. And wherever he is, I hope it’s one he cherishes.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

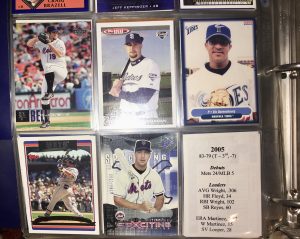

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

Not quite in the same category as the folks you describe is Doc Medich. The veteran was picked up on waivers from Seattle on September 26, 1977. Three days later, he was the starter for the Mets in Pittsburgh. He went 7 innings allowing but 6 hits and 3 runs, but was the loser in his only Met game. The game lasted a snappy 2hrs & 9 minutes and was winessed by an announced “crowd” of 2,504. He beame a free agent at the end of the season, signed with Texas and pitched in the bigs for another five years. He finished his career with a 124-105 3.78 mark with 16 shutouts and a couple of saves.

Ah yes, Doc Medich. He’s part of a related subgroup of Marginal Mets — “Guys Apparently Never Photographed as Mets.” I’ve seen one picture of him in a Mets uni, a lousy AP shot from the Pittsburgh series. Never anything in color, and Topps never got him.

My Medich custom card is a shot of him as a Yankee, Photoshopped into Mets togs. Sigh.

And Medich was an actual doctor who went up into the stands a couple of times to try to help people who appeared to be having heart attacks.

A good guy, and good for him!

There haven’t been that many people in MLB history that were on the field for the final at-bat of a franchise before its relocation to greener pastures AND making their major league debut at the same time. So Joe’s a pretty special guy!

[…] Rey Ordoñez 1998: Todd Pratt 2000: Melvin Mora 2001: Mike Piazza 2002: Al Leiter 2003: David Cone 2004: Joe Hietpas 2005: Pedro Martinez 2008: Johan Santana 2009: Angel Pagan 2012: R.A. Dickey 2013: […]

[…] Rey Ordoñez 1998: Todd Pratt 2000: Melvin Mora 2001: Mike Piazza 2002: Al Leiter 2003: David Cone 2004: Joe Hietpas 2005: Pedro Martinez 2008: Johan Santana 2009: Angel Pagan 2012: R.A. Dickey 2013: […]