Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Hark ye yet again—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it.

1967 was a strange year for the New York Mets.

The 1966 club had achieved a pair of rather dubious high-water marks, losing fewer than 100 games for the first time in its history and escaping the National League cellar. (They lost 95 and finished 7.5 games ahead of the Cubs.) The end of that season marked a turning point, as original general manager George Weiss retired and handed over the reins to Cardinals import Bing Devine.

Devine immediately took a buzzsaw to the roster, cutting players and striking deals. Before spring training, Devine had traded away Ron Hunt, the team’s first non-ironic homegrown star; original Met Jim Hickman; and Dennis Ribant. And he kept tinkering throughout the season — 54 players appeared in a game for the ’67 Mets, including 27 pitchers, which tied a big-league record. Thirty-five of those players were making their Met debuts; 12 were making their big-league debuts. The constant turnover annoyed fans, who showed up at Shea in reduced numbers, and helped precipitate the early departure of manager Wes Westrum. He resigned before the club’s final road trip, telling the press that “I just don’t want to manage this club anymore.”

Devine’s tenure would only last a single season; he returned to St. Louis after Stan Musial stepped down as GM, replaced in New York by Johnny Murphy, a former Yankees star reliever who’d been Weiss’s top scout. Devine’s ’67 Mets landed back in the basement, managing 61 wins, or 1.13 per Met. Still, Devine did lay the groundwork for better days. He moved Whitey Herzog from the third-base coach’s box to the front office, where he’d build a phenomenal farm system (which should had been the precursor for his managing the ’72 club, but that’s another post). And Devine’s new Mets included ones who’d soon ascend to immortality: Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Don Cardwell, Ed Charles, Cal Koonce and Ron Taylor. (As well as one who got away, Amos Otis.)

They weren’t all gems, of course, as that 61-101 record might have told you. There was Don Bosch, a center fielder hyped as the second coming of Mickey Mantle who turned out to be about half the Commerce Comet’s size; Phil Linz, famous as a harmonica-wielding Yankee agent of chaos; and a host of answers to future trivia questions, such as Dennis Bennett, Bill Graham, Joe Grzenda, Joe Moock, Les Rohr, Bart Shirley and Billy Wynne.

One such trivia question might involve Al Schmelz. Schmelz was recalled from Jacksonville at the end of August and made his big-league debut at Shea on Sept. 7, relieving Jerry Hinsley in a game the Mets were losing 8-2. The first batter Schmelz faced was Tim McCarver, who flied to right. He gave up a double to Mike Shannon, who got thrown out at third, and then surrendered a long home run to Julian Javier. His final line was 2 IP 3H 1 R 1 ER 1 BB 2 K. Schmelz then sat in the bullpen for more than two weeks before being called upon to pitch the top of the ninth in Houston. He allowed a triple to Chuck Harrison but contributed a scoreless inning; the Mets lost, 4-2.

And that was Schmelz’s career.

Of course, a player’s stint in the big leagues isn’t the entirety of his career — it’s more like the part of the iceberg above the waterline, a bright spot that gives little hint of what might be underneath. I began my seriocomic, largely doomed exploration of that career because of baseball cards.

It started the summer before college, when I ill-advisedly traded a Rickey Henderson rookie card to a pair of neighborhood kids in return for “every Met card you have.” That made the kids go away, which is all I’d wanted, but also left me with a grab bag of mid-80s Mets cards. I’d collected from 1976 through 1981, and had the singularly terrible idea of bridging the gap between my childhood collection and the new cards that had fallen into my lap — one of those light-bulb-going-off moments, except the light bulb is a warning that you’re going to spend thousands and thousands of dollars on a hobby you’ll never be able to escape.

That bad idea sent me foraging in St. Petersburg, Fla.’s baseball-card shops, until I had every Met from ’76 on. And then the dominoes started falling in grim succession: Why not get every Mets card released by Topps back to 1962? Why not get every Met card released by Fleer, Donruss, Score and Upper Deck? Why not get Topps cards for guys who were on the Mets’ roster in a given year but never actually got a Mets card? Why not get the Topps cards for Mets from all their non-Met years? I didn’t know about high numbers, or what rookie cards cost, or that Al Weis shared a rookie card with Pete Rose. But I’d learn. Oh boy, would I learn.

One thing I learned was that 34 of 1967’s 35 new Mets had baseball cards in one form or another, even if they came with asterisks attached. Some appeared attired as members of other teams: Bennett (Red Sox), Shirley (Dodgers), Nick Willhite and Wynne (Angels). Hal Reniff, sad to say, is a Yankee. Rohr shared a 1968 rookie card with Ivan Murrell, a Houston outfielder wearing one of Topps’ blank black hats; future pitching coach Billy Connors shared a ’67 rookie card with fellow Cub Dave Dowling.

Graham and Moock never got Topps cards, and their careers ended before minor-league baseball cards became common. Enter a veteran card dealer named Larry Fritsch. Fritsch had connections at Topps and issued several series of cards he called One Year Winners, giving cardboard immortality to players who’d never had a card before, and using photos shot by Topps back in the day. His efforts saved Graham and Moock from anonymity — Graham as a Tiger, Moock as a Met.

But there was no card for Schmelz. Just as there was no card for Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts, or Rich Puig. Those unfortunate players became the core of what I called the Lost Mets — a grim fraternity filled out by Brian Ostrosser, Leon Brown and Tommy Moore. (Ostrosser and Brown got minor-league cards so dismal they would have been better off with nothing; Moore got a lone card during his tenure with Florida’s late-80s Senior League circuit. Greg still thinks that card should count, an obvious error of aesthetic judgment I have chosen to forgive. I have that card, of course — my hypocrisy is of the flexible variety.)

I cobbled together cards for the Lost Mets using a Xerox machine to copy taped-together assemblages of old black-and-white team photos, computer print-outs and a Xerox of the ruffled pages of a phone book, which I felt looked old-timey but actually just looked weird. That was another bad idea that opened a chasm beneath my feet. Inevitably, I decided those paper cards wouldn’t do — the Lost Mets needed cards that looked like actual baseball cards, at least to an untrained and/or mildly forgiving eye. And so I started hacking around on Photoshop — a complex program about which I knew absolutely nothing — to create them.

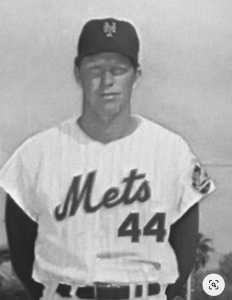

The problem, I soon discovered, was that it was easier to find Jimmy Hoffa than to locate a decent color photo of Al Schmelz in a baseball uniform. A couple of Mets yearbooks had pictures of him grouped with other guys invited to camp — but they were always small and in black and white. He’s in the team photos — in glorious color, no less — in the ’67 and ’68 yearbooks, but of course he’s in the back, almost completely blocked by his teammates.

So I did the best I could. I took apart the ’67 team photo to make Frankenschmelz — Schmelz’s face, upper chest and arms, combined with Cardwell’s stomach and belt, and the 4 from Ken Boyer‘s uniform number, used twice. As a Photoshop noob, I had no idea about image quality or how to bend and distort pixels so pasted bits of another photo don’t look like they’re floating atop the original. The result is horrible — and, to my shame, it’s still one of the top results if you Google Schmelz. (“Al Schmelz,” by the way, also seems to be German for “aluminum smelter,” which for years made Googling him even stranger.)

A decent Schmelz photo became my white whale, and I the grim Ahab hell-bent on finding it. I even wrote to the man himself — twice — with no luck.

At some point during this increasingly insane pursuit, I realized I’d lost sight of the man behind that maddeningly nonexistent photo, and so I tried to figure that out. Here too Schmelz proved elusive, with only the barest outlines of his college and minor-league career emerging from articles that interchangeably referred to him as Al and Alan.

A hulking California kid, he transferred from junior college to Arizona State, where he starred in both basketball and baseball before concentrating on the latter. 1965 was his breakthrough — he won a College World Series title as a Sun Devils, with his teammates including Sal Bando, Rick Monday and Duffy Dyer, then followed that by playing for the Sioux Falls Packers of the Basin League and the Alaska Goldpanners, where he was part of a formidable starting rotation: Schmelz, Seaver, Danny Frisella and Andy Messersmith.

At the time the Basin League and the Goldpanners were showcases for amateur players who were either honing their skills or trying to catch scouts’ eyes. It worked for Schmelz, who was signed by the Mets in 1966 and went 12-0 for Auburn, fanning 133 in 113 innings. A promotion to Williamsport didn’t go as well — Schmelz walked far too many hitters in both stops — but the talent was obviously there, and during 1967’s spring training Westrum talked up the big right-hander as a possible member of his relief corps.

Schmelz’s 1967 tenure with Williamsport was largely the same as his time in ’66, but up he came for his cup of coffee. It was after that that things get murky. In the offseason he was one of three players offered to the Senators for the right to make Gil Hodges the Mets’ manager, with Washington choosing Bill Denehy over Schmelz and Tug McGraw. Schmelz was cut in spring training in 1968 and then went 0-11 pitching for Jacksonville, Vancouver and Memphis. His season ended on Aug. 28, when the Mets sent him home with the vague but ominous diagnosis of “a sore arm.”

In 1969 Schmelz pitched for Memphis, Pompano Beach and York. The results were unimpressive and in December the Mets sold his contract to the Royals. He never appeared in a professional game again, his career over at 26. He became a commercial real-estate broker in the Phoenix area, showing up in occasional accounts of Sun Devils alumni events, baseball charity functions and fantasy camps. I’ve never seen a retrospective of his career or a quote from him in a newspaper.

I can figure out the basics well enough — Schmelz suffered an arm injury in an era where they couldn’t be repaired, like so many pitchers did. The Mets hoped he’d regain his form, or learn to pitch differently, and so they shuffled him between different minor-league outposts and lent him out to other organizations — Vancouver and York were affiliates of the A’s and Pirates at the time. But beyond that I know nothing — not what he threw, not what the Mets thought of him, and not how he views his career. Even his page for the wonderful SABR Bio Project turns out to be a frustrating tease. He’s a visible object that’s but a pasteboard mask.

And so I kept doggedly looking for that elusive photo. Schmelz popped up in shots taken at a baseball fantasy camp in Arizona, but beyond the fact that he was decades past his playing days, he was wearing a 1990s Met hat and what I interpreted as a faintly mocking smile. In 2010 a snapshot showed up on eBay showing Schmelz wearing 16 instead of his more familiar 44. Of course it was in black and white. Inevitably, Schmelz’s face was mottled by shadows, his expression suggesting he’d just had a gulp of expired milk. I bought it anyway, added color and turned it into a new Lost Mets card to replace the Frankenschmelz. It was an improvement. It still looked terrible.

I took some solace in discovering I wasn’t the only Schmelz hunter out there. There’s a thriving subculture of baseball hobbyists whose quest is to assemble photos of everyone who’s ever played big-league ball, in every uniform they wore, and Schmelz is one of the names that elicits sighs.

One of that subculture’s leading figures is Keith Olbermann, who combines impressive investigative skills with an amazing memory for details. Olbermann had helped me in the earliest days of my Schmelz quest, noting (apparently from memory) where Schmelz could be found in the team photos. He was familiar with Topps’ simultaneously voluminous and haphazard photo archives, whose contents are the gold standard for baseball photo hunters, and reported that there was nothing for Schmelz. That was disappointing but no surprise — in 1967, as one of its early labor actions, the nascent players’ union told its members to stop posing for Topps. That’s why late-60s Topps cards feature lots of old photos and hatless shots in airbrushed uniforms.

As my quest continued, Olbermann became an eagerly awaited herald of Schmelz sightings. He unearthed a casual shot of our quarry on the grass in spring training with other Mets pitchers. It was in color — eureka! — but not very good — ugh! A group shot from the Instructional League came to light — apparently that’s when Schmelz wore 16. I found black-and-white photos from his Goldpanners tenure. But nothing was revealed that might let me end my hunt.

And then finally, in late 2016, the white whale was sighted and the crews were able to land a harpoon. Olbermann found and shared a Dexter Press shot of Schmelz, this time wearing 48.

A shot in color.

A shot where Schmelz is facing the camera.

A shot where Schmelz doesn’t look like he’s been kneed in the groin or is trying to make a hasty getaway.

Of course I made a new Lost Mets card — I honestly can’t remember if it was the third, the fourth or some even higher number. By now I was pretty good at Photoshop, adept at sharpening and color-correcting and other subtleties the program offers. And the image Olbermann had so kindly shared was big enough and clear enough to work with.

It came out OK. But only OK. Somewhere in the transition from digital image to card stock, Schmelz’s face wound up a little too red, and fuzziness crept into the formerly sharp details. Holding the finished card in my hand, I sighed and reached for my keyboard to open Photoshop and try again. And then I stopped myself. What I had was better than anything I’d had before, and better than what I’d recently imagined might be out there. More than that, I sensed, simply wasn’t possible with the mysterious Alan George Schmelz.

So the crews reeled in their harpoons and rowed back to the ship, and the great white whale vanished beneath the waves again. I assume he flipped his tail derisively as he went. That’s OK, as is the fact that I know he’s out there somewhere. Maybe I’ll run across him one day; for now, I’m content to stay in port.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

Love it. The greatest Met ever starts his career in 1967, and Al Schmelz represents that season. Perfect. Only Mets fans honor their history like this. And to top it off, the guy’s name sounds like someone who Woody Allen talks about in one of his movies, like the guy who made pastrami and chopped chicken livers sandwiches at the neighborhood deli.

Aluminum Smelter! You can’t make this stuff up!

If only the Phillies or Indians name was pulled out of that hat……

I’m guessing he’s a distant cousin of the equally immortal Chris Schwinden. (Excerpt I’m guessing ol’ Schwindy had his own card, despite his abbreviated Met tenure.)

Ha. Yeah, everybody has a card these days. Should, say, Johneshwy Fargas make the roster, I’ll be ready.

[…] 1962: Richie Ashburn 1963: Ron Hunt 1964: Rod Kanehl 1965: Ron Swoboda 1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice 1967: Al Schmelz 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1977: Lenny […]