Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I kicked off my half of our Met for All Seasons posts with a remembrance of Rusty Staub, my first favorite player — and how he turned out to be an ideal choice. That’s no surprise — Staub was a legendary Met regular, an iconic Met role player, and a beloved alumnus, as well as one of those rare players who crossed the white lines to become a New York City presence as well.

My second favorite player, the one who replaced Rusty in my heart after his shameful exile to Detroit, was a less obvious choice — more “oh yeah that guy” than legend, and a man for whom New York was one in a series of addresses and not a home. But he did just as much to make me a Mets fan. And maybe more.

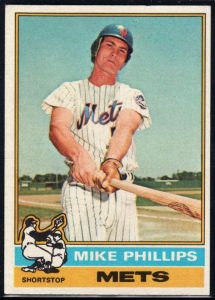

Why did I fall in love with Mike Phillips, utility infielder for the mid-Seventies Mets, and our Met for All Seasons for 1976? The simple answer is because I was a weird kid.

In 1976 I was already a Mets fan, thanks to Rusty Staub and my mom. (Getting to watch Tom Seaver helped too.) But the Mets weren’t an all-consuming passion. I also loved to draw and make up stories. Mostly these were about superheroes — Star Wars was still a year away from capturing my imagination, but I loved my Mego action figures, the ones that were basically dress-up dolls for boys, complete snaps in the back of their fuzzy tunics and weird clawlike mittens instead of gloves. (My friends and I would have been horrified by that description, but look at these things and tell me it isn’t true.) I didn’t care for the Marvel superheroes, which had an arriviste whiff, but I staged endless epics starring Batman and Robin, sometimes joined by Superman and even Aquaman, with his otherworldly shock of highlighter-yellow hair.

When I couldn’t cart around my collection of superheroes, I brought them to life on paper, which was in ready supply for the child of two academics. I primarily drew Batman and Robin, but eventually I tired of familiar caped crusaders and tried something new: superheroes of my own invention.

I don’t remember the name of the superhero I invented, but I do remember he had a secret identity, because every masked man needed one of those. And the secret identity I chose for my creation was “Mike Phillips.”

I know what you’re thinking, but I’m pretty sure you’re wrong. Yes, I was a Mets fan by the mid-Seventies. But I don’t think I was enough of a Mets fan to have cribbed that name from a utility player who’d arrived in 1975 on a waiver-wire deal. Nor do I recall my parents being conversant enough with the roster to bring up part-timers and fill-ins. I think it really was a coincidence.

But it would turn out to be a pretty important one. In 1976 I started collecting baseball cards, which supercharged my fandom by giving me biographies and stats and factoids I could pore over and memorize. And so I was stunned when I saw that there was a 1976 New York Met with the same name as the superhero I’d drawn on the backs of about a thousand no-longer-needed SUNY class handouts and memos. Clearly this was the hand of fate, stretched down from the baseball gods to a seven-year-old kid on Long Island and indicating, This is the path. Follow it to happiness. (Or, well, since you’re a Mets fan, at least something happiness-adjacent.)

Like I said, I was a weird kid. Maybe that’s why the hand of fate pointed at a journeyman infielder — Seaver would have been too easy. But maybe there was more to it than that.

Phillips was born in Beaumont, Texas, and attended MacArthur High in Irving, a school whose most famous sports alumnus is Brian Bosworth. He lettered in baseball, basketball and football, which caught the attention of the San Francisco Giants. They drafted him in 1969 and he reached the big leagues in ’73 as a backup to Chris Speier despite never having hit over .250 at any minor-league stop.

Phillips’ tenure with the Giants would form the blueprint for his career: He wanted to play and never really got the chance. As a rookie, he hit .240 and saw action at shortstop, third and second. The Giants liked his versatility, and he came to spring training in 1974 as the favorite for the third-base job. But the club opted for Steve Ontiveros instead. Phillips got into 100 games, but only hit .219 and made 19 errors. He wanted out, and the Giants granted him his wish in ’75, putting him on waivers.

Enter the Mets, who needed a replacement for Bud Harrelson and his increasingly gimpy knees. Phillips got the bulk of the time at shortstop, and while the results weren’t the stuff of statistical wows — a .256 average and a 0.5 WAR — both team and fans appreciated his gutty play and knack for clutch hits, rewarding him with more than 330,000 write-in votes to the All-Star Game. (He wasn’t selected.) But while Phillips’ positional versatility brought up the old “Jack of all trades” saw, his defensive stats were a reminder of the “master of none” thing — he led National League shortstops with an ugly 31 errors.

1975 wasn’t the springboard Phillips had hoped for. His defensive improved in ’76, but so did Harrelson’s knees, and Phillips was back to sharing time and moving around the infield. In ’77, the Midnight Massacre meant the end of his Met career, as Doug Flynn‘s arrival and a .209 average made him superfluous. The Mets shipped him to St. Louis for Joel Youngblood, making me probably the only Mets fan in the world who was more upset about June 15’s third-paragraph dog-for-cat trade than the departures of Seaver and Dave Kingman.

As with Staub, I continued to carry a torch for my lost hero. Phillips found himself in a familiar situation with the Cardinals: He wanted to be a starter and wasn’t given the chance. I knew this by following box scores and was even ticked about it than Phillips was — and when my parents took me to see a Mets-Cardinals game at Shea in 1978, I arrived bearing a declaration of war.

My message for Cardinals skipper Vern Rapp was as lengthy as it was angry:

HEY VERN IF YOU WANT A BENCH WARMER GET A HEATING PAD BUT DON’T USE MIKE PHILLIPS

A couple of points should be made here.

1) To be read by anyone in the Cardinals’ dugout, this message would have required multiple bedsheets and poles and the cooperation of at least a section’s worth of fans, assuming the wives of the 1969 Mets weren’t on hand, as they probably weren’t for a regular-season game nine years later. I didn’t use multiple bedsheets, however — I used a single sheet of letter-sized construction paper.

2) Said single sheet of letter-sized construction paper wasn’t white, but forest green. It was unreadable 20 inches away, to say nothing of 200 feet.

3) I have no idea what 1978 Mets-Cardinals game we attended, but the first one was May 29, and Rapp had been fired on April 25, replaced by Ken Boyer.

Did I make the least-effective banner in the history of spectator sports? It’s got to be at least a contender.

Phillips moved on from the Cardinals to the Padres and finally to the Expos, with his career less an arc than a flat line. It ended in 1983 much as it had begun, with him sticking around because he was useful but never really getting to play. Montreal was a strange and undoubtedly frustrating limbo in which he was equal parts player, coach, instructor and none of the above. The Expos released Phillips three times in 16 months: in May ’82, June ’83 and finally for keeps in September ’83. His final career totals: 412 hits over 11 years, a .958 fielding percentage, and one season with a WAR above 1. After his career, Phillips went into marketing, which eventually brought him back into baseball — he was director of corporate sponsorships for the Rangers and oversaw all corporate revenue for the Royals. That’s an interesting second life for a player — two high-ranking jobs that had little to do with the nuts-and-bolts experience of being a player.

But let’s go back to 1976, the best year of Phillips’ career — and the one in which he meant everything to me.

My one memory of Phillips as an actual Met is seeing him hit a leadoff homer, with his name immediately popping up in yellow capital letters on the screen, which was Channel 9’s way of noting round-trippers. That’s the entire memory — I have no context beyond it, and when I sat down to write this piece, I wouldn’t have sworn that what I recalled was accurate. Plenty of memories from when you’re seven years old turn out to be incomplete, distorted or fundamentally incorrect.

So I checked. In late June, the Mets rolled into Wrigley Field for a three-game series with the Cubs. The team was 34-37, far off the pace in the N.L. East, and Phillips was hitting .207. In the first game, Phillips played short and hit leadoff. He struck out looking against Ray Burris to begin the game, but doubled in the third, tripled in the fifth, homered in the seventh, and grounded a single in the eighth. That made Phillips the third Met to hit for the cycle, joining Jim Hickman and Tommie Agee. The Mets won, 7-4. The next day, they romped to a 10-2 win with Phillips scoring three runs and homering — but in the eighth. In the third game, the Mets completed the sweep with a 13-3 bludgeoning of the Cubs, moving to 37-37 on the year. Phillips led off again — and, as I discovered to my delight, he opened the game with a home run to deep right off Rick Reuschel.

That home run was part of the best week of Phillips’ career. He arrived at Wrigley with four home runs as a big-leaguer and left with seven. He hit for the cycle. And soon after that, he was named the National League’s Player of the Week.

So my memory was accurate: I’d seen him go deep off Reuschel on our Sony color TV, watching Channel 9 on a summer Sunday afternoon. Did that week, that game and that moment in particular make me the Mets fan I’ve been pretty much ever since? It might have.

I adopted a utility player as my favorite because of a coincidence involving names and tried to will him, with all the fervor a seven-year-old could muster, into becoming the star I’d imagined. That was too much to ask for a career, but not for a week. For a few days, Mike Phillips really was a superhero. And he donned his cape at the perfect time to transform a little kid’s curiosity and interest into a lifelong passion. The hand of fate may have been pointing somewhere unexpected, but it really was showing me the path.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

I really liked Mike Phillips, too.

He was a very useful player during those couple of years, as Harrelson was injured a lot during that time.

And it was nice to hear continuously (back then) that he was one of a few Mets to hit for the cycle.

Ok, unsurprisingly I am now 1-for-2. My pick for ’76 was Dave Kingman, whose 2 month pacing of Roger Maris’ home run record was one of my earliest baseball recollections. And once I started following baseball in earnest, one of my favorites was the guy Phillips was traded for, Joel Youngblood. Not sure why – I just liked him, he had a cool name, and I was a kid. Also, in retrospect, he was a pretty solid player.

Not quite sure which is my favorite here: “I have no idea what 1978 Mets-Cardinals game we attended, but the first one was May 29, and Rapp had been fired on April 25, replaced by Ken Boyer.”, a.k.a. the troublesome lack of accounting that foils all seven-year-olds’ evil plans, or “Little does he know every letter is from the same weird kid in East Setauket, N.Y.”, which perfectly fits the unassuming expression of the subject.

But, ah, weren’t we all weird kids? Let’s just say I’m glad stuffed toys from the 90s couldn’t talk.