Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I’m solid gold

I’ve got the goods

They stand when I walk

Through the neighborhoods

—David Naughton

In 1989’s Field of Dreams, the fresh-faced kid Ray Kinsella and Terence Mann picked up hitchhiking seemed to have emerged from another time. Specifically, as Ray noted to Terence while the young man with baseball ambitions napped in the back seat, “The way he described towns, and finding you a job so you could play on their team. They haven’t done that for years.”

Many moons (and Moonlights) later, it occurs to me another youthful ballplayer, who was most certainly of his time, would seem fairly alien in our time if he materialized in 2020 and shared with us the story that captivated the four-decades-ago version of us.

“Yo, thanks for the lift,” you can imagine him saying if we picked him up by the side of the BQE today. “Turns out my Trans-Am needs a tune-up and I didn’t wanna take the subway to the ballpark in Queens. I get recognized from the pictures of me they got up in all the cars. I’m from Brooklyn, see, and the team is relying on me to not only be their best player, but their biggest star. I don’t wanna sound like I’m bragging, but people treat me like a pretty huge deal around here, what with me being a hometown guy, hitting a little over .300 once, getting my homer total in the mid-teens annually and generally driving in close to eighty runs. I also run pretty good, make occasional fancy-looking catches and wear my uniform so it practically sticks to me. Listen, you can drop me off outside when we get there. The guards’ll let me in. They know me. Everybody knows me.”

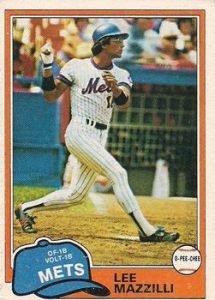

Lee Mazzilli in 1980 was an idol the likes of which we just don’t have today, yet he was surely who we reveled in idolizing back then. If deconstructing the whole Archie Graham/Burt Lancaster dynamic challenged the sanity of the contemporary characters played by Kevin Costner and James Earl Jones at the end of the ’80s, we began the ’80s confident Mazzilli was the Met on whom the sun and moon rose and set, and it didn’t seem the least bit crazy in our world.

Lee Mazzilli lit up our Mets fan lives, such as they were.

I don’t want to imply Lee Mazzilli wasn’t a good ballplayer. He was a fine ballplayer. The advanced statistics which didn’t exist at the height of his Met fame indicate we weren’t overstating his skills merely because we didn’t have anybody else to get terribly excited about. For three years — 1978, 1979, 1980 — Mazzilli’s OPS+ topped 120, the sign of a hitter performing well above average. In 1979, the season he went to the All-Star Game and made us extremely proud, he finished sixth among all National Leaguers in offensive WAR, per Baseball-Reference. Nobody in the NL cobbled together a better power-speed number (accounting for combined home run-stolen base prowess) in 1980 than Mazz. Granted, I feel a bit like Disco Stu trying to impress investors in a 1997 episode of The Simpsons by citing how healthy disco record sales were in 1976, but when Mazzilli was at his best, he was quite good.

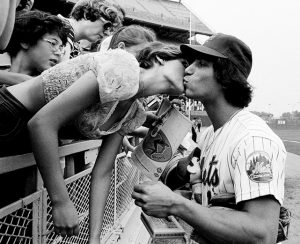

But from the vantage point of what the game looks like in 2020, it’s difficult to imagine that Lee Mazzilli having anything close to the same impact. Hardly anybody leads a team with 16 home runs anymore unless the season is 60 games long. Hardly anybody is greenlighted to steal 41 bases anymore, nor risk getting thrown out 15 times trying. No franchise attempts to appeal to the largest possible cohort of customers by building itself around a 6’ 1”, 180-lb. center fielder/first baseman whose numbers are better than OK, but never mind his numbers because a) he’s a looker and b) he’s local.

He’s from Brooklyn!

He’s Italian!

You gotta come see him in Queens!

We’ll give you his poster!

This was the essence of the Mets’ sales pitch c. 1980. It worked on those of us predisposed to buy whatever it was the Mets were selling.

Mazz — rather than Maz, because two z’s equaled more pizzazz — was born in Brooklyn in 1955, which coincidentally was the year the Dodgers won their only World Series in Brooklyn. Or was it a coincidence? Mazzilli was drafted in the first round by the Mets out of Lincoln High School in Sheepshead Bay in 1973, one year after The Boys of Summer was published. Whatever his intention with his literary masterpiece, Roger Kahn tapped into something almost tangible that spoke to a larger temporal truth. After the municipal havoc of the late ’60s and early ’70s, the New York air — including in the suburbs, where a lot of former Brooklynites had migrated — was thick with wistfulness for a lost age, baseball’s and otherwise. Chronologically, we weren’t so far removed from what is often reflexively referred to as the golden age of New York baseball, when the Yankees were a flannel-clad dynasty who blew cigar smoke at the Copacabana and the Giants were a more stolid outfit, but a couple of times they were very surprising and very exciting. Yet it was the Dodgers who were the Boys of Summer, the Dodgers who remained retroactively aspirational. The Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s were a vibrant if sepia-toned living memory a generation after they ceased to exist — and the 1950s of the Brooklyn Dodgers a place that seemed real enough if people who remembered it talked about it enough. There were no more Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1970s, but a ballplayer from Brooklyn showing up to play ball in Queens…a ballplayer who plays the same position as Mays, Mantle, Snider and, for that matter, DiMaggio…hey, you can hear somebody thinking, that’s something we can sell.

I doubt compelling biography is why the Mets drafted fourteenth in the nation the ambidextrous speedskater who snuck into Shea with his friends in the middle of the night in 1969. There’s no way it was because his dad had been a welterweight boxer before turning to piano-tuning that called up Lee to stay in 1976 and presented him with the center field job in the spring of 1977 despite his hitting only .195 during his previous September’s audition (albeit with a couple of ninth-inning homers, one of them a walkoff shot that torpedoed the Pirates’ faint pennant hopes). Yet once Mazzilli put down roots at Shea, it was hard to miss the inherent qualities he had coming and going in disparate directions, suitable for someone who knew how to use both hands. He innocently represented a link to the nebulous good old days in Flatbush as much as he potentially pointed toward a more fortuitous future in Flushing for a franchise that needed anything it could that would make people forget about the endless and endlessly abysmal present.

A stream of Brooklyn-bred ballplayers have populated Met clubhouses dating to the Mets’ beginnings, spanning Piggy (Joe Pignatano) to Figgy (Nelson Figueroa) and beyond, depending on how you view Dellin Betances of Manhattan having played scholastic ball across the East River at Grand Street Campus. John Franco went to Lafayette, like Bob Aspromonte before him and Kevin Baez after him. Willie Randolph went to Tilden. Shawon Dunston went to Thomas Jefferson. Tommy Davis was a man among lads at Boys High School. Ed Lynch and Paul Lo Duca were born in the borough (Paul’s dad was Lee’s sandlot coach), though they grew up elsewhere. Before Todd Frazier was from Toms River and Neil Walker was from Pittsburgh, Met announcers reminding you which Mets were from Brooklyn could have constituted its own version of Wayne Randazzo’s #HowieBingo card.

Also, the fella who’s owned part or essentially all of the team these past forty years, you might have noticed the last time you were in a certain Rotunda, is originally from Brooklyn.

Birthplace or where a player spent his youth is a briefly referenced biographical note these days, give or take the occasional overdose of Neil Walker or Todd Frazier info. But being from Brooklyn when it was learned who Mazzilli was really seemed to mean something, especially within the media when the wounds from when the Dodgers deserted the borough still lingered in the collective Metropolitan Area psyche. Dick Young and Jack Lang covered those Dodgers. Maury Allen and Steve Jacobson rooted for those Dodgers. Given how regularly Mazzilli’s background was mentioned in stories and during broadcasts, I find it impossible to believe being The Kid From Brooklyn didn’t give him a leg and two arms up on standard ambidextrous rookies who hit .250.

In a city whose baseball stars in previous eras included DiMaggio, Berra, Rizzuto, Camilli, Furillo and Antonelli, to name a bunch, being Italian-American didn’t hurt, either, at least in terms of fomenting an image for a 22-year-old ballplayer who was tabbed starting center fielder the same month Rocky won Best Picture at the Oscars. You know what Rocky Balboa nicknamed himself in the movie, right? The Italian Stallion. You know what everybody started calling Lee Mazzilli during his first full season? The way baseball had worked for a century, it didn’t hit the ear as impolitically as it does today. Carl Furillo was “Skoonj” to his Dodger teammates, short for scungilli (he ran the bases as slow as a snail). Al Rosen was the Hebrew Hammer in the ’50s. Juan Marichal was the Dominican Dandy in the ’60s. Emil Frederick Meusel, who played left for John McGraw’s Giants in the ’20s, was called Irish because he was said to “look Irish”.

Still, for all the marquee Italian surnames that have graced Met rosters — Franco, Piazza, Conforto, to name three — no Met was ever quite cast in the role of Great Paisan Hope the way Mazzilli was. Pignatano was the longtime bullpen coach when Mazz arrived. Joe Torre was Lee’s mentor as a teammate before being named Met manager. Pete Falcone and John Pacella joined the pitching staff in due time. But only Lee Mazzilli from Brooklyn was the Italian Stallion. At a cultural moment when Sylvester Stallone was starring in the film that won the Academy Award and John Travolta was dancing like nobody’s business as Tony Manero — in Bay Ridge, no less — maybe the Italian Stallion wasn’t such a bad thing to be known as. Salute!

In those days, anything for a hook, anything for a story, anything to make you forget sixth place. These days, low-key pregame heritage theme nights notwithstanding, I’m failing at fathoming any individual player being promoted quite so sincerely ethnically, even if it’s as well-intended as could be. This year I saw a segment on the MLB Network, recorded during Spring Training, wherein Mark DeRosa queried Michael Conforto as to whether he preferred calling what he put on his pasta “sauce” or “gravy,” and the question was a little jarring to my 2020 sensibilities. Honestly, it never occurred to me whether Conforto, a Met since 2015, was anything but Metropolitan-American. I knew he was from somewhere in the Pacific Northwest. I had no idea whether he was or wasn’t Italian, even if the last name is something of a giveaway (FYI, Michael chose “sauce”).

Long before Conforto was born in 1993, but well after the Dodgers left town in 1957, you had this Italian kid from Brooklyn who wanted to play baseball more than anything. When Lee was coming of age, youth soccer had yet to be widely organized and video games had yet to be invented. Football may have been in the process of surpassing baseball as a television sport, but nobody strenuously challenged baseball’s claim as “the national pastime” any more than anybody thought there was anything a little off-color in calling a baseball player “the Italian Stallion”. Mazzilli could have pursued the Winter Olympics as a teen; he was that good a speedskater. But Lee was a baseball man in the making all along. “I played stickball, punchball, slapball, softball,” he recalled for Steve Serby in the Post in 2007. “Played ’em all.” What could have been a more All-American New York baseball story than Lee Mazzilli’s? Whose story could have been truer to what New York’s romantic self-image had been throughout the twentieth century?

Contrast the recollections of Mazzilli’s hardly misspent youth with this 2017 report on the continuing decline in youth baseball across the five boroughs: “No one culprit is blamed for this loss. Instead, it’s pinned on an array of factors: competition from other sports like soccer, the increased popularity of digital devices, rising league fees, longer school days and even immigration, which has in some neighborhoods replaced the Louisville Slugger with a cricket bat. The sport itself, from the recent rise of travel teams to the age-old quirks of baseball — its pace, its difficulty — also gets blamed.”

In other words, good luck trying get a slapball game going on a block near you. (And this was before the pandemic.)

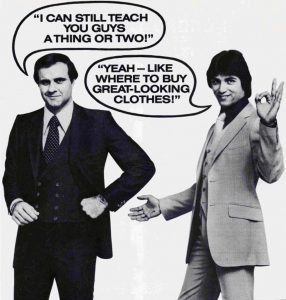

So, sure, we still have ballplayers of Italian descent, like Mazzilli is. And sure, we still have ballplayers who went to high school in Brooklyn, like Mazzilli did. And yes, though they’re in short supply and haven’t made much impact of late — the last three on the Mets were Billy Hamilton, Sam Haggerty and the presumed alive Jed Lowrie — we still have ballplayers who aim to hit both lefthanded and righthanded like Mazzilli could. Yet I’m having a hard time living in the modern era and imagining somebody coming to the fore now the way Mazzilli did then and having somebody weave a narrative around him the way it was done. “Italian Stallion from Sheepshead Bay trackin’ ’em down in center, swipin’ bags, beltin’ one out now ‘n’ then — and the ladies can’t take their eyes off him!” sounds like a 1950s Madison Avenue ad man’s dream.

Jerry Della Femina was a Madison Avenue ad man in 1980, in the business since the 1960s. He was also born in Brooklyn, in 1936, and he became the Mets’ ad man when Nelson Doubleday and his Brooklyn-born minority partner Fred Wilpon bought the team. The Mets hadn’t much advertised prior to 1980. Casey Stengel was all the salesman they needed in 1962, then big, beautiful Shea Stadium sold itself long enough to attract attendance until the Mets won a World Series. For a while after 1969, it was enough to make sure the papers printed the time the game started. But by 1979, at the end of a decade when the Mets couldn’t have hemorrhaged more ticket-buyers had they tried, the goodwill was gone. (Shockingly, 1977’s hastily created “Bring Your Kids to See Our Kids” campaign, despite featuring Mazzilli and his demographic peers, didn’t much move the needle following the trade of Tom Seaver.)

The new owners turned to Della Femina, who conjured “The Magic is Back” as the Mets’ slogan. Print ads played up that these new Mets will be sort of like those old Dodgers you, Mr. Maybe Ticket Buyer, remember from the ’50s in that they’ll make you care when they inevitably break your heart. The 1980 Mets weren’t far enough along to get beat by modern-day Bobby Thomsons and Don Larsens in October, but one miracle at time. Implicit in the pitch was these new Mets, or at least these Mets you haven’t looked too closely at lately, have some guys who can make a little Magic en route to getting competitive. As 1980 dawned, the first player Della Femina thought of to illustrate the point was the Met who mesmerized what was left of the masses in Flushing in 1979. That was Mazzilli, a.k.a. the Italian Stallion, coming off the season that not only earned him his All-Star berth but his poster day.

Lee Mazzilli Poster Day predated the Mets’ more consolidated marketing efforts. It was a one-off. They weren’t having them for Kevin Kobel or Bruce Boisclair. Lee was among the batting average leaders coming out of the gate in ’79, and if nobody was coming to the park to see him in person based on his hitting, perhaps they’d schlep to Shea to get a big damn poster of the guy they were hopefully watching on TV. Lee was photographed posing on the dugout steps, hatless and handsome. Saturday July 7 vs. the Padres was chosen for the giveaway. It was also San Diego Chicken Day — and the day the name Mettle was announced as the identity of the team mule (you’d think they’d have invested in a stallion). The promotional onslaught drew 14,048. The Mets lost, 11-3. Lee went 1-for-3, leaving his average at .332.

Ten days later, bespectacled Lee wore his cap and his rather tight road uniform in Seattle, representing the Mets on the National League All-Star Team alongside last-minute injury replacement John Stearns. Pinch-hitting for Gary Matthews, who had subbed in for starter George Foster, Mazzilli stepped in to lead off the eighth and whack an opposite-field home run off the Rangers’ Jim Kern to tie the game for the NL. Lee batted left, lined it to left and hopped on home plate after circling the bases. Waiting to congratulate him was the cream of the senior circuit: Dave Winfield of the Padres; Joe Morgan of the Reds; Ron Cey of the Dodgers; Pete Rose of the Phillies; Keith Hernandez of the Cardinals; Gary Carter of the Expos. In the NBC booth that night, Cincinnati ace Tom Seaver — usually in uniform for these affairs — praised his former teammate. “I had the pleasure of playing with him in New York for a couple of years when I was still with the New York Mets,” Seaver said over a replay. “He’s really become a fine hitter, he’s really learned the strike zone, and he goes with the pitch now, he’ll go with that ball, a lot of strength.”

“There are not too many players in All-Star Game history who did what Mazzilli just did,” Tony Kubek added. “First All-Star at-bat, and he hits a home run.”

Because this was the era when the National League never lost to the American League, it was just a matter of staying tuned and finding out how the NL would pull it out. In the top of the ninth, Kern walked the bases loaded, and with two out, was relieved by Ron Guidry of the Yankees. Batting for the National League? Lee Mazzilli of the Mets, this time from the right side. It was a miniature Mayor’s Trophy Game at the Kingdome. Mazz, having learned the strike zone, just like Seaver said he had, worked the count to three-and-one before calmly taking ball four. Mazzilli did a baton move with the bat, twirling it as he tossed it, much as he might have with a broom handle beating his buddy at stickball back home. It was only a walk, but it was the go-ahead RBI just the same. When the National League held on in the bottom of the inning, it stood as the winning RBI.

For a few minutes, you could forget the Mets were stuck in the basement of the NL East for a third consecutive year. You could forget the Yankees had won the last two world championships. You could overlook the All-Star Game MVP award being voted to Dave Parker for his two breathtaking outfield assists. You didn’t care that Mazzilli’s average had been steadily dropping since they gave out his poster. On the stage where the attention of every baseball fan in North America was focused, Lee Mazzilli was the star among Stars. He was ours. The kid from Brooklyn. The kid from Queens. The Met who belonged up there. We hadn’t had anybody who made us feel this way since Tom Seaver had the pleasure of playing with him in New York.

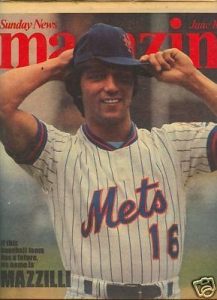

All Mazzilli had to do the rest of 1979 was not get hurt (Dan Norman crashed into him in the outfield but Mazz missed little time) and not finish below .300 (his average landed at .303), and we’d fully believe what the Daily News plastered on the cover of its Sunday magazine in June: “If this baseball team has a future, its name is MAZZILLI.”

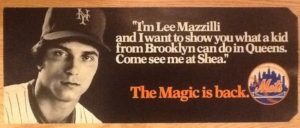

Not too much pressure to put on the now 25-year-old Mazzilli, though Della Femina Travisano & Partners certainly tried, making him one of the centerpieces of The Magic is Back’s transit advertising. Lee’s head shot greeted MTA riders with the pull quote intended to boil down his most Metsian appeal: “I’m Lee Mazzilli and I want to show you what a kid from Brooklyn can do in Queens. Come see me at Shea.”

Slowly but surely, some did. Attendance increased. So did the wins. The Mets started to transfer the Magic from conceptual to concrete, closing in on .500. There was a string of abracadabra wins, highlighted by the one on June 14 when Steve Henderson socked the three-run, bottom-of-the-ninth homer that completed a dazzling comeback from down 0-6 for a 7-6 win over the Giants. Though that case of Saturday night pennant fever is rightly remembered as The Steve Henderson Game, it was Mazz who, with two out, drove in the first run the Mets posted in the ninth, and it was Mazz who scored the second, when he came home on new Met Claudell Washington’s single.

Lee didn’t return to the All-Star Game in 1980, having gotten off to a slow start, but July turned out to be The Lee Mazzilli Month. He homered on the first of July, then the second, then the third, then in the first game of a July 4 doubleheader. He walloped 11 home runs in all in July to go with 25 RBIs. His OPS measured 1.136, even if that was an unidentified metric at the time. On July 15 in Atlanta, the night the Mets were finally prepared to even their record — something they hadn’t done this late in a season since Mazzilli was a September 1976 callup — Lee did something better than hit. He hit back.

With the 41-42 Mets ahead by five runs in the top of the ninth and Doug Flynn on first, Torre instructed starting pitcher Pat Zachry to lay down a bunt. The sight of somebody squaring with his team comfortably in front apparently got under the skin of Braves reliever Al Hrabosky. The Mad Hungarian (speaking of nicknames that likely wouldn’t gain traction in 2020) registered his disapproval by sailing a pitch over Zachry’s head. It didn’t come close to plunking Pat, but it was clearly aimed nowhere near the plate.

On deck was Mazzilli. He didn’t care for Hrabosky’s sudden loss of control and was ready to channel the feistier side of his Stallion persona. Jawing ensued, benches emptied and, after Zachry’s final bunt attempt went for strike three, Mazzilli got even and then some, blasting his ninth home run of the month out of Fulton County Stadium. It felt as good as the previous eight combined.

Lee watched his homer take off into orbit; he outright moseyed around the bases; and he called to the Mad Hungarian as he crossed the plate, “How’d you like that? Don’t be throwing at my pitcher.” The Mad Hungarian grew madder still and the benches emptied again, but the Mets would not be denied their 42nd win against 42 losses. “I can’t say I was right,” Mazzilli admitted upon reflection. “I probably was wrong, but I’d do it again.”

The Mets wouldn’t do much again of what they’d been doing in the high summer of 1980. From 42-42, they got to 43-43, then a few weeks later to 56-57. Then the bottom dropped out of their no longer Magical season, with injuries to just about everybody (except durable Mazzilli) taking their toll. The Mets lost 38 of their final 49 games, the Magic allusions reverted to a punch line and, despite overall good numbers, Lee’s legacy as a New York star in the specific mold of Willie, Mickey, the Duke and Joltin’ Joe became something very quickly shunted into the past tense. The kid from Brooklyn started in center the Old Timers Day in 1977 when the four center field icons strode through Shea’s center field gate together and inspired Terry Cashman to pen his paean to 1950s New York baseball royalty. The same kid was still out there on Old Timers Day in 1980 when the Mets honored Duke Snider on the occasion of his induction into the Hall of Fame and his 1955 Dodgers for the 25th anniversary of their lone Kings County championship (did we mention Fred Wilpon was one of the owners by then?).

But it hadn’t been a steady throughline in center for Mazzilli from the summer of 1977 to the summer of 1980 because the Mets knew they had another center fielder coming, a speedy minor leaguer named Mookie Wilson. Also, they had a void at first base as 1979 wound down once they traded erstwhile 96-RBI man Willie Montañez to Texas. Thus Torre, who made his initial mark in the bigs as a catcher, asked his home-borough protégé to do as he once did: learn to play first base at the major league level. Lee considered himself “born to play center field”. He had modeled himself on his former Met coach Mays, going for the basket catch as often as he could. But Lee didn’t really have a great arm at a position where that mattered, no doubt a symptom of having grown up using both of them equally.

When 1980 began, with 15 September starts in ’79 behind him, Lee Mazzilli was the Mets’ Opening Day first baseman. For close to two months he remained anchored in the infield. Come June, Torre opted to entrust first to defensive whiz (and Queens boy) Mike Jorgensen and sent Mazz back to what he considered his natural position. All was centered in Lee’s world until Wilson was promoted from Tidewater in September. Henceforth, Mazzilli was a first baseman for the rest of 1980.

Lee was back in center to begin 1981, but by mid-May, that was Mookie’s pasture for keeps, before and after that year’s strike. Lee began to see time in left because first base was now where Torre sought playing time for a couple of Recidivist Mets less limber than Mazz or Jorgy. Rusty Staub had been a splendid right fielder before he was shipped to Detroit five years earlier. Now, at 37, Le Grand Orange was a recovering designated hitter whose bat was considered too valuable to bench. Dave Kingman, meanwhile, hadn’t improved defensively while he’d been away from Shea, so after his return to left field went awry, Torre opted for his big slugger to play first, which meant Staub was going to be a pinch-hitter deluxe.

Amid all of Torre’s maneuvers, Lee Mazzilli, the Met at the heart of their 1980 advertising, no longer stood front and center in the Mets’ plans. He wasn’t hitting, he wasn’t comfortable fielding (one night he groped helplessly as he lost a ball in Shea’s lights) and the clean-cut kid had grown a mustache. Not that the mustache had anything to do with his average dropping from .280 in ’80 to .228 in ’81, but the kid sure suddenly seemed much older.

More changes were in order once the split season proved no panacea. Torre was let go as manager at the end of 1981. GM Frank Cashen brought in his old Oriole compadre George Bamberger of Staten Island. The Verrazzano-Narrows connection to Mazzilli didn’t mean much to the new skipper or the wary GM. Cashen, who inherited Mazzilli, spent the winter trying to make over a ballclub that had not contended in a full season since Lee was a Single-A prospect in Visalia. Come December, Cashen would trade Flynn for Kern, the pitcher who gave up the All-Star home run to Mazz. Kern never pitched for the Mets, because he was packaged in February, along with backup catcher Alex Treviño and ambidextrous pitcher Greg Harris, for the player who started that 1979 All-Star Game in left for the National League, the player who was replaced by Gary Matthews who, in turn, was pinch-hit for by Lee Mazzilli.

The Mets had gotten George Foster. It was a bombshell. Foster had led the NL in RBIs three years running, from 1976 to 1978. He drove in 90 in ’81, a season that was shortened by about a third by the strike. He had the kind of all-around run-producing power that…well, basically nobody with the Mets ever had. Combine him with Kingman and Ellis Valentine, who Cashen had picked up the year before, and that’s a helluva middle of the order Bamberger could look forward to writing in. Foster was the left fielder, to be sure. Valentine, when he was healthy, was a top-notch right fielder, with every bit the caliber of cannon Parker showed off in the Seattle All-Star Game. They’d each flank Wilson, who had established himself as the center fielder for the foreseeable future. Kingman’s glove they’d stick at first and, if the Mets had a lead (and why wouldn’t they, with all this hitting?), they could take him out and insert Jorgensen for defense. Rusty, now a player-coach, would continue to lurk as a late-innings weapon.

And Lee Mazzilli? Where the hell would Lee Mazzilli, the Brooklyn kid who’d invited straphangers to come see what he could do in Queens less than two years before, play?

There was some taking of ground balls in the middle infield in St. Pete, but Mazzilli had never played there before and the Mets had plenty of second basemen and shortstops in camp, so the answer turned out to be Texas. Before Spring Training was over, on April Fool’s Day 1982, Cashen sent the Metinee idol of the late ’70s and the earliest ’80s to the Rangers for two minor league pitchers. That they were highly regarded minor league pitchers didn’t fully cushion the shock waves from Lee Mazzilli going from main man of the Mets to excess baggage to ex-Met in almost no time at all. It wasn’t quite as stunning as the Mets getting George Foster, but it was close.

This was perfect. Mazzilli was a 31-year-old veteran now, released by Pittsburgh, where he’d been since 1983 after his ’82 with Texas proved a short stay. The Rangers traded him to the Yankees for none other than fellow fading pin-up Bucky Dent. It was a trade that helped nobody. One could cynically say the same for Cashen’s big move to acquire Foster and sign him for five years, but that would be oversimplification. No, Foster wasn’t nearly the power hitter for the Mets as he’d been for the Reds, especially in his first miserable perception-sealing year, but he did help shift the Mets to the edge of the map, buying the GM time to put the club there to stay. George had been reasonably productive for the Mets from 1983 until the first part of 1986, and with the Mets having transformed themselves in the intervening years into the dominant force in their division, the ol’ left fielder could probably glide to the postseason with his teammates and be celebrated as a champion should they get that far.

But Foster was unhappy with reduced playing time and asserted to reporters that he thought a racial element influenced Davey Johnson’s decision to use him less. It seemed unnecessary to point out that of the three productive outfielders for whom Johnson was striving to ensure playing time, two — Wilson and Kevin Mitchell — were Black. However Foster’s dismay was portrayed, the first-place club decided the .227 batting average that accompanied it was eminently dispensable.

Another bat in his stead couldn’t hurt, even if the bat the Mets chose hadn’t been exactly tearing up Three Rivers Stadium. But Mazzilli was more than the sum of his stats. He was Lee Mazzilli. He was as good a story in 1986 as he was in 1980. Better, maybe, because instead of his having to fill the role of a star, the vet from Brooklyn could just chip in. From the moment he returned, he did that in several ways down whatever stretch the Mets needed to clinch the NL East. He homered to tie the Cardinals in the ninth inning one Saturday afternoon in a game NBC was covering. Bob Costas intimated Saturday Night Fever was back at Shea. Overall, Mazz hit .276 in reserve duty. He also mock-socked “sportscaster” Joe Piscopo in the human bobblehead portion of “Let’s Go Mets!” video. Not that you make roster decisions based on such plays, but it’s hard to imagine George Foster doing that.

For those of us who were diehard Mets fans when Lee Mazzilli was our biggest star, those of us who would have been diehard Mets fans in any year basking in the glow of anybody they told us was our biggest star, Lee’s homecoming was as big a spiritual victory as any the 1986 regular season had to offer. Fans like us wore our fealty to the Mets of Flynn, Taveras, Stearns, Henderson, Youngblood, Swan, Zachry, Allen and, most of all, Lee Mazzilli as a badge of honor. We hadn’t ditched the Mets just because they sucked. We just died harder as circumstances dictated. Believe me, amidst the curtain calls, high-fives and high-profile music videos, nothing was sweeter than getting to redeem that badge in exchange for the redemption of Mazzilli’s career.

From 1976 to 1981, the kid from Brooklyn never got closer to a World Series than his TV. Same from 1982 to 1985 during his exile from 126th Street. Ah, but in October of 1986, in an actual World Series taking place at actual Shea Stadium, Lee Mazzilli, batting lefty, pinch-singled to start the eighth-inning rally that tied Game Six, which the Mets would go on to win, and, batting righty, pinch-singled to start the sixth-inning rally that tied Game Seven, which the Mets would go on to win. At last, Lee and we knew what the Magic was.

There was a lot to take in during the 1986 World Series, but watching Mazz and Mookie score in rapid succession on Keith Hernandez’s single off Bruce Hurst in Game Seven stood out for me. It was like watching a decade of Mets baseball cross the plate all at once. Mazzilli was at the heart of a half-assed rebuilding that lacked mortar. Wilson was the Met who’d begun to make him superfluous. Mazz was pinch-hitting for Sid Fernandez, who’d taken over for Ron Darling, the starter in the seventh game who simply didn’t have it that night the way he did in Games One and Four. Darling was a Met in 1986 because in 1982 Cashen traded Mazzilli to get him — him and Walt Terrell, the latter of whom was traded for Howard Johnson, who was also a Met in 1986. Darling and HoJo and Mookie all contributed substantially throughout the year to what was three innings from becoming a world championship baseball club. But here, too, was Mazzilli, broken free of the past, not representing a mythic Brooklyn that no longer existed if it ever did. He was Mazzilli in the present, at a Shea Stadium full of fans who needed no come-ons to jam the joint. Here was Lee Mazzilli, 1986 New York Met, having come up with literally one big hit after another to help win us win the World Series, just like we dreamed of in 1980 on those days and nights when we began to permit ourselves to dream such crazy dreams.

It’s the most timeless Lee Mazzilli tale of all.

For a comprehensive look at Lee Mazzilli’s life and career in and out of baseball, I recommend the excellent SABR biography written by Friend of FAFIF Jon Springer. You can find it here.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1968: Cleon Jones

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1985: Dwight Gooden

1986: Keith Hernandez

1987: Lenny Dykstra

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Michael Conforto

2016: Matt Harvey

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

2020: Pete Alonso

I grew up in Sheepshead Bay, and there were neighborhood guys who remembered seeing Lee Mazzilli play ball in high school just a few blocks from our house. That made him ours, in a way no other athlete from that generation was. And one of the best storylines of ’86, in a year of awesome storylines, was Mazz coming back home just in time to win a World Series with us. Your article encapsulates it perfectly.

My sister dated a guy from Sheepshead Bay during Mazzilli’s rookie year. They were the same age, too. Excitedly, I asked if he knew him. He didn’t.

There went what little appeal he had.

As I understand the story, my Future Wife was 16 and my Future Sister-In-Law 13 when there was a huge argument over a Mazzilli t-shirt.

A tug-of-war with said shirt commenced. At one point, Future Wife let go, causing Future SIL to strike herself in the nose while holding the shirt. Blood “all OVER” the shirt.

At which time, Future Wife paused, then remarked “you can have it.”

As long as they settled their differences amicab-Lee.

I have Mazzilli’s autograph, and here’s how it happened:

It was the Summer of 1977, and the Mets made a Bowling appearance at Gil Hodges Lanes on Ralph Avenue in Canarsie, Brooklyn. The best bowlers that night were Jerry Grote and special guest Professional Bowler Mark Roth.

Anyway, we were 12, and so our friend’s older sister went into the bar in the Bowling Alley, to follow Mazzilli. She came out with 3 autographs and gave us one each.

As these things do, the evening ended in a riot in the parking lot, as the fans swarmed the players for autographs, and the Mets raced for the bus.

I ran to a car where Bob Apodaca, Ron Hodges, and Craig Swan totally ignored me as they put their stuff in the trunk and got out of Dodge.

And then the cops let the mentally challenged young man who started the riot, onto the bus, and gave him all their autographs.

Good Times!

Apodaca, Hodges and Swan had lived through 1973. They knew something about being swarmed.

My own Mazzilli encounter here.

You know, you don’t always recognize famous people when we are outside of our regular environment, especially when the TV is only 5 inches!

I loved that question to Swoboda, though. Very esoteric. When I was 11 or 12, and getting autographs in the parking lot at Shea, I was too starstruck to barely say anything.