Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series [1] in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

In the mid-80s, while I was off at boarding school, I got a letter from my mother. That wasn’t odd, but what was inside was. My mother had sent me a folded-up article she’d cut out of Cosmopolitan, and amended it with a sentiment more typical of her: Typical Cosmo bullshit, but thought you’d enjoy.

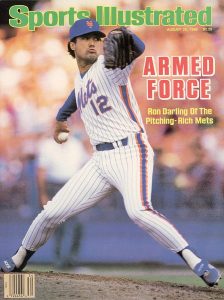

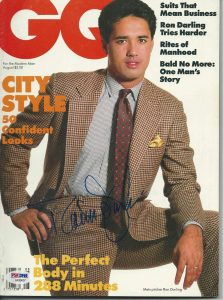

When I unfolded it, I understood — it was about Ron Darling [2]. Darling was a mainstay of such magazines then, and why not? He was a young and handsome star pitcher for the Mets. To those qualities he added a handful of ineffable somethings — style, glamour, and ease with the bright lights. And he had an intriguing background, one not exactly standard for a professional ballplayer. For openers, he was the son of a Chinese-Hawaiian mother and a French-Canadian father, a proto-Benetton ethnic mix that made vaguely cringy references to “exotic good looks” de rigueur when he was written about outside of the sports pages. He spoke French and Chinese, and he’d studied French and Southeastern Asian history at Yale. If I’d told you back then that George Plimpton — he of the Paris Review bylines and the good-schools accent — was going to invent a fictional Mets ballplayer, you’d have expected a creation a lot more like Darling than Sidd Finch. Gary Carter [3] gave Darling the nickname Mister P, short for Mister Perfect, and writers for Cosmo, GQ and other publications fell over themselves to agree.

[4]Two baseball generations later, Darling is part of the mighty SNY triumvirate with Gary Cohen and Keith Hernandez [5] and a mainstay of postseason broadcasts. But something funny happened along the way. When you think of Hernandez, you draw a straight line between the mustachioed, vaguely piratical first baseman of the mid-80s and the raffish color guy he’s become. But that straight line isn’t as easy to draw with Darling. He’s thicker and grayer, true, but hey, aren’t we all? I think it’s that Darling invokes his career less frequently than Hernandez, typically discussing pitching mechanics and grips without grounding them in his own experiences. And when he does reference his own playing days, he’s generally self-deprecating about himself and his accomplishments. The odd effect is a Mets icon whose triumphant second act has somehow diminished his career instead of enhancing it.

[4]Two baseball generations later, Darling is part of the mighty SNY triumvirate with Gary Cohen and Keith Hernandez [5] and a mainstay of postseason broadcasts. But something funny happened along the way. When you think of Hernandez, you draw a straight line between the mustachioed, vaguely piratical first baseman of the mid-80s and the raffish color guy he’s become. But that straight line isn’t as easy to draw with Darling. He’s thicker and grayer, true, but hey, aren’t we all? I think it’s that Darling invokes his career less frequently than Hernandez, typically discussing pitching mechanics and grips without grounding them in his own experiences. And when he does reference his own playing days, he’s generally self-deprecating about himself and his accomplishments. The odd effect is a Mets icon whose triumphant second act has somehow diminished his career instead of enhancing it.

But the Yale pedigree and the Mister P nickname led to a lot of mistaken assumptions to go with that typical Cosmo bullshit. Darling’s father, Ron Sr., was a foster kid who’d spent his childhood being passed around New England farm families. (The nickname R.J. is a back formation of “Ron Jr.”) He served with the Air Force and was stationed in Honolulu, where he met Luciana Mikini Aikala, a teenaged girl being raised by her grandmother because her mother had died in childbirth and her father had left home. Their son would call his parents “stray dogs,” adding that they were “perfect for each other.” When Darling was three, his father was discharged and a former foster family offered him a job in a machine shop in a mill town outside of Worcester. Darling grew up in Millbury, in a development of ranch houses built for servicemen returning from World War II. One of his favorite childhood memories was collecting garbage with his father and taking it to a pig farm — not exactly the stuff of Skull & Bones confessions.

Athletic prowess helped get him to Yale: The Darlings’ Millbury ranch house sat on an acre of land, where Ron Sr. built a baseball diamond. But that also required a lot of hard work, and not just Darling’s. His parents took extra jobs to send four boys to college, and expected that the results would meet their family’s high standards. Darling had been a standout high-school quarterback, but at Yale the job went to someone else and he was put in the secondary, which he disliked. He turned to baseball, where his coach saw his arm at shortstop and turned him into a pitcher. He went 11-2 as a sophomore; the next year, he faced Frank Viola [6] of St. John’s in the NCAA regionals, pitching 11 no-hit innings before losing 1-0 in the 12th on a flurry of small but fatal misfortunes. Among those watching the game were Red Sox legend Smoky Joe Wood [7] and New Yorker legend Roger Angell, who chronicled the Darling-Viola duel in 1981’s “The Web of the Game.” [8]

Darling passed up his last year at Yale to sign with the Rangers; he became a Met, along with Walt Terrell [9], in an April 1982 trade for Lee Mazzilli [10]. He was called up in September 1983, facing Joe Morgan [11], Pete Rose [12] and Mike Schmidt [13] as his first three enemy hitters [14]. (Darling loves telling that story, but it’s usually Gary who notes that he struck out Morgan and Rose and got Schmidt to ground out.) The next year, he arrived for keeps, as did the Mets and their instant ace Dwight Gooden [15].

Gooden is one of the reasons Darling has been able to poor-mouth his career without getting called on it. When you’re pitching behind the best pitcher in baseball, it’s tough to get noticed, but cover Gooden’s blinding numbers and Darling’s shine pretty brightly. In ’85, he was 16-6 with a 2.90 ERA, and threw nine shutout innings in the fabled “clock game” against St. Louis, the one that turned when Darryl Strawberry [16] homered off the Busch Stadium clock in the 11th. In ’86 he was 15-6 with a 2.81 ERA and a 1.53 ERA in three World Series starts, earning his ring by vanquishing the team he grew up rooting for — he’d been at Fenway for Carlton Fisk [17]‘s legendary Game 6 walkoff. He had a deadly pickoff move (particularly for a right-hander) and was a superb fielder, winning a well-deserved Gold Glove in ’89. In all, Darling went 99-70 with a 3.50 ERA as a Met, which are pretty good numbers to plug into any rotation.

[18]Not being mid-80s Gooden shouldn’t be a sin, but Darling also carried the perception that he could have achieved more than he did. Davey Johnson [19] groused that he walked too many guys; fans groused that he got himself into trouble and wound up with too many no-decisions. Pro and amateur critics saw a common thread — that Darling was too smart and too much of a perfectionist for his own good.

[18]Not being mid-80s Gooden shouldn’t be a sin, but Darling also carried the perception that he could have achieved more than he did. Davey Johnson [19] groused that he walked too many guys; fans groused that he got himself into trouble and wound up with too many no-decisions. Pro and amateur critics saw a common thread — that Darling was too smart and too much of a perfectionist for his own good.

Which was probably true. Darling’s combination of plus fastball, slider and curve was good enough to let him shove hitters around, but he wanted more than that. He wanted to befuddle them, working to arrange at-bats so they’d culminate in the perfect pitch put in the perfect location. Sometimes he’d make that pitch; other times, he’d outthink the hitter so thoroughly that he’d also outthink himself, or miss that perfect location by a fraction of an inch on a three-ball count. Later in his career, he added a split-fingered fastball to his repertoire, and arguably fell too in love with the new pitch, to the detriment of his secondary pitches. Darling wasn’t gifted with Noah Syndergaard [20]‘s firepower, but he strikes me as a forerunner of Noah in one respect: He might have had a higher W-L percentage if he’d had a lower IQ.

Darling represents 1989 in our A Met for All Seasons series, which probably wouldn’t be his pick — he was 14-14 that year and stuck in a clubhouse undergoing a transition it wouldn’t survive, as the baton got fumbled in the handoff between the heroes of ’86 and a new generation of Mets. (Darling did become teammates with Viola, uniting the college adversaries from the game immortalized by Angell.) The next year he wound up in the bullpen and then under the knife, and as the 1991 season cratered the Mets traded him to the Expos for Tim Burke [21]. Darling spent two weeks looking miserable in tricolor motley before being shipped to Oakland, where he won the 100th game that had cruelly eluded him as a Met. He started the final game [22] before the ’94 strike and was released the next year, on his 35th birthday.

The upside of that was Darling avoided his first-ever trip to the disabled list, which was a point of pride for him; the downside was his career was over, and he had to figure out what to do with the rest of his life. He likes to tell a revealing story [23] about coming home hoping to celebrate his newfound freedom with his family, only to find everyone was busy with play dates, tennis matches and other daily routines he knew nothing about. It was a surreal experience that showed him he’d spent years on scholarship while others made daily life work around him. Darling spent a few years decompressing from baseball, then came back to it as a broadcaster for the Nationals’ inaugural 2005 season. A year later, he moved to SNY. His early reviews as a broadcaster weren’t kind, but he worked doggedly at his new profession and was soon hailed as one of the best in the business.

In reaching that level, perhaps Darling has figured out what sometimes eluded him on the mound — that it’s not all on him. He’s the calm axis of the SNY booth, a vital balance point between Cohen’s rock-solid play-by-play and teed-up inquiries and Hernandez’s vortex of fascinating, maddening chaos. It’s a role where he can work deftly and efficiently to make both his partners better — the equivalent, perhaps, of picking a pitch meant to yield a grounder to short rather than a hitter frozen in horror at the plate. Maybe Darling runs down his own career because he sees now what he wishes he had seen then. But I hope he also sees that the lesson was learned — and that his resume is one to be proud of. Even by Darling family standards.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962 [24]: Richie Ashburn

1963 [25]: Ron Hunt

1964 [26]: Rod Kanehl

1965 [27]: Ron Swoboda

1966 [28]: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967 [29]: Al Schmelz

1968 [30]: Cleon Jones

1969 [31]: Donn Clendenon

1970 [32]: Tommie Agee

1971 [33]: Tom Seaver

1972 [34]: Gary Gentry

1973 [35]: Willie Mays

1974 [36]: Tug McGraw

1975 [37]: Mike Vail

1976 [38]: Mike Phillips

1977 [39]: Lenny Randle

1978 [40]: Craig Swan

1980: [41] Lee Mazzilli

1981 [42]: Mookie Wilson

1982 [43]: Rusty Staub

1983 [44]: Darryl Strawberry

1985 [45]: Dwight Gooden

1986 [46]: Keith Hernandez

1987 [47]: Lenny Dykstra

1988 [48]: Gary Carter

1990 [49]: Gregg Jefferies

1991 [50]: Rich Sauveur

1992 [51]: Todd Hundley

1993 [52]: Joe Orsulak

1994 [53]: Rico Brogna

1995 [54]: Jason Isringhausen

1996 [55]: Rey Ordoñez

1997 [56]: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998 [57]: Todd Pratt

2000 [58]: Melvin Mora

2001 [59]: Mike Piazza

2002 [60]: Al Leiter

2003 [61]: David Cone

2004 [62]: Joe Hietpas

2005 [63]: Pedro Martinez

2007 [64]: Jose Reyes

2008 [65]: Johan Santana

2009 [66]: Angel Pagan

2010 [67]: Ike Davis

2011 [68]: David Wright

2012 [69]: R.A. Dickey

2013 [70]: Wilmer Flores

2014 [71]: Jacob deGrom

2015 [72]: Michael Conforto

2016 [73]: Matt Harvey

2017 [74]: Paul Sewald

2018 [75]: Noah Syndergaard

2019 [76]: Dom Smith

2020 [77]: Pete Alonso