Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

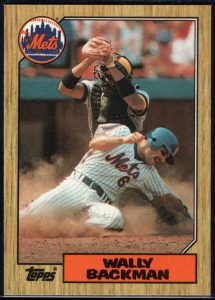

Looks back at the ’86 Mets often pair Wally Backman with Lenny Dykstra, his fellow partner in grime (and co-star in the ’86 year-in-review video’s super-cringey “Wild Boys” montage). Which makes sense: Backman and Dykstra were both undersized players who seemed able to will themselves on base, inevitably getting their uniforms filthy in the process, and were blunt-spoken to the point of brashness and often far beyond it. And both players’ heroic stints in New York were followed by more difficult chapters, ones that made their legacies uncomfortable.

But Backman deserves more than to be remembered as half of a scrappy/hustling platoon with Dykstra. He deserves his own reckoning — as not only a throwback player but also a throwback manager, hyper-aggressive in confronting umpires and dissecting enemy skippers. Backman could have been dropped in any of a number of baseball eras, transplanted perfectly to jittery old black-and-white newsreels or faded 60s film — a fitting contemporary for John McGraw, Earl Weaver, or Billy Martin. Unfortunately for him, he’s one of the last of that lineage — these days, front offices aren’t looking for the next Billy Martin, particularly when they fear such a hire would come with off-field baggage. That baggage is part of Backman’s legacy too.

But let’s go back to the beginning. Walter Wayne Backman grew up as a baseball rat in Beaverton, Ore., spending untold hours in a vacant lot his parents had turned into a regulation-sized baseball field for the neighborhood kids — and honing his skills under the eye of his father, a railroad switchman who’d briefly been a Pirates farmhand. The Mets drafted him in 1977, and he hit .325 for Little Falls as a 17-year-old shortstop.

The bat was there. So was the gritty, no-prisoners style. The fielding, however, was not — which would be an ongoing problem as the Mets tried to figure out where Backman fit. In 1978 Backman hit .302 in Lynchburg and won a league championship, but he also had a .947 fielding percentage and led the league in errors.

The Mets shifted Backman to second base, which is where teams hide middle infielders who can’t field, knowing all too well that a lot of balls still pass through second basemen’s hands, sometimes literally. Still, Backman’s glove was less of a problem there than at short, and his other talents were undeniable. He hit .323 for Tidewater in 1980, and when Doug Flynn hurt his wrist, Backman got the call. He made his debut on Sept. 2, the same day as Mookie Wilson, singling in his first at-bat off Dave Goltz and driving in Claudell Washington. He still couldn’t take a legal drink.

That’s another thing about Backman: He was one of the old-guard Mets from the ’86 club, preceded only by Wilson (by a few minutes) and Jesse Orosco (by a year). They’d be followed by a second wave of ’83 and ’84 players as the team found its focus under Davey Johnson, then bolstered by the ’85 and ’86 arrivals. Dykstra belonged to that third wave — when Backman made his Mets debut, Dykstra was still playing high-school ball.

Backman’s first tour was promising — he hit in 18 of 26 games — but 1981 was a washout, as he struggled for playing time and tore his rotator cuff. The injury lingered into 1982, which was unfortunate: The Mets had cleared the middle infield for Backman and Ron Gardenhire by shipping out Flynn and Frank Taveras, but Backman’s fielding was poor and his season was cut short by a broken collarbone. 1983 started off promisingly, but soon turned sour, as Backman agitated for a trade after being sent down to Tidewater in May.

He didn’t know his career was about to turn around. At Tidewater Backman found a champion in Johnson, who called him “a foxhole player, a guy who will keep grinding and grinding until the job is done.” His new skipper showed confidence in him as a second baseman too, tutoring him at the same position he’d held down as an Oriole. When Johnson got the call as Mets manager for 1984, our year in question, Backman came with him.

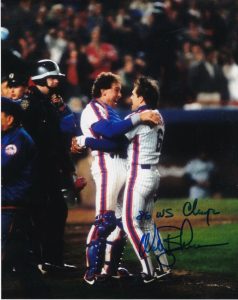

Johnson was also a believer in the value of platoons, which maximized Backman’s value. His scrappy superpowers didn’t work against lefties — for his career, Backman hit .294 right-handed but just .165 as a southpaw. Under Johnson Backman split time with Kelvin Chapman and then with Tim Teufel in 1986. That season would make him a legend — his drag bunt leading off the bottom of the ninth in Game 3 of the NLCS set up Dykstra’s walkoff, Gary Carter drove him in as the winning run in Game 5, and he scored what would eventually prove the decisive run in the epic Game 6. One of my favorite shots of the World Series comes from the on-field celebration after Game 7 — a hug amid the scrum that united the grimy, sweaty Backman and a beaming Carter.

Johnson was also a believer in the value of platoons, which maximized Backman’s value. His scrappy superpowers didn’t work against lefties — for his career, Backman hit .294 right-handed but just .165 as a southpaw. Under Johnson Backman split time with Kelvin Chapman and then with Tim Teufel in 1986. That season would make him a legend — his drag bunt leading off the bottom of the ninth in Game 3 of the NLCS set up Dykstra’s walkoff, Gary Carter drove him in as the winning run in Game 5, and he scored what would eventually prove the decisive run in the epic Game 6. One of my favorite shots of the World Series comes from the on-field celebration after Game 7 — a hug amid the scrum that united the grimy, sweaty Backman and a beaming Carter.

The next season the always blunt Backman would be front and center in Mets dramas, calling out Darryl Strawberry‘s absences by telling the press that “nobody I know gets sick 25 times a year.” Strawberry threatened to punch Backman in the face, calling him “that little redneck” — an escalation that took an odd turn when Backman didn’t know what a redneck was. “Is it like a red-ass?” he asked, using baseball argot for a hothead. (Brought up to speed by reporters, he seemed genuinely hurt by the accusation.) Such tunnel vision seems baffling, until you remember that Backman was a lifelong baseball rat who’d been playing pro ball since he was 17.

The Mets traded Backman after ’88 to make room for Gregg Jefferies — in part because Johnson was certain he could tutor Jefferies at second the way he’d taught Backman. That didn’t work, and Backman’s departure would be much mourned as the increasingly colorless Mets drifted and stumbled and then collapsed. But for all the talk of grit and fire, it’s doubtful Backman would have made a difference: He had good numbers for the Pirates in 1990, but was a part-timer otherwise, and his career came to an end when the Mariners released him in May 1993. He was just 33.

If that had been the end of Backman’s baseball life, it would still be a pretty interesting one: a 5-foot-9 platoon guy who couldn’t really field but bit and clawed and scraped his way to a 14-year big-league career, a World Series ring, and never having to buy his own beer in New York. But Backman had a second act as a manager, which would prove … complicated.

Like a lot of former players, Backman needed a couple of years away from the game to decompress. But he returned to it in 1997 as manager of the Catskill Cougars, a team in the independent Northeast League. From there Backman went on to manage the Bend Bandits and the Tri-City Posse. He managed like he played: aggressive, combative, and endlessly hustling, a combination that became known as Wally Ball. But it wasn’t all dirty uniforms — Backman also gained a reputation as an able teacher of young players and an astute judge of enemy managers’ weaknesses. Billy Martin is the obvious comparison, but his real model was Johnson. Johnson, in turn, had learned at the knee of Earl Weaver, who’d tutored him as a minor-league infielder in the Baltimore system. A Backmanesque figure in his own right, Weaver quite literally grew up in the Browns’ and Cardinals’ clubhouses of the 1930s — his father had handled both St. Louis teams’ dry-cleaning. Backman would have been perfectly at home there.

Backman’s independent-league success got him a job in the White Sox farm system, where he succeeded in Winston-Salem and Birmingham but then was let go after campaigning a little too openly for Jerry Manuel‘s job in Chicago. He jumped to the Diamondbacks and the California League, where he was the 2004 Minor League Manager of the Year with the Lancaster JetHawks. He was in the running to replace Art Howe in New York, but dropped out amid rumblings that he’d get the Diamondbacks’ job instead. That happened in November 2004: Wally Ball was coming to the Show.

At least until it wasn’t. Backman’s managerial tenure lasted four days. The issue was a New York Times piece about Backman’s hiring, one that noted his off-field troubles: a DUI arrest, a restraining order connected to his first marriage, an arrest following a 2001 drunken altercation with his second wife, and a bankruptcy declaration. What’s interesting is the off-field messes weren’t the focus of the Times story, but its end — it was basically color to show that Backman was intense.

The problem was that the Diamondbacks hadn’t known about that stuff.

They belatedly did due diligence on the manager they’d hired and decided to unhire him, a moment that has loomed over the rest of Backman’s life. Backman protested about the unfairness of it all, pointing out that George W. Bush had a DUI and was president; three years later, his second wife, Sandi, told ESPN’s Jeff Pearlman that “I hope for nothing but [the D-Backs] to lose every game.”

And on the surface it did seem a bit unfair. The restraining order had been obtained ex parte, meaning only the party seeking it need be present when granted, and such orders aren’t uncommon in bitter divorces. Sandi Backman said the 2001 incident had been overblown, and the idea that Wally would hit her was “comical.” When the Diamondbacks inquired, a friend of Sandi Backman’s who’d been involved in the drunken altercation blamed herself for escalating things, saying she’d been out of line.

But the Diamondbacks found the police report alarming reading — among other things, it said the friend had resorted to keeping Backman away from Sandi with a baseball bat, breaking his forearm with it. (The bat was from the ’86 Series; Backman still has a titanium plate in his arm.) Backman had been on probation for the DUI, and officials in the Washington county where it happened found out about the 2001 incident through the Times. It was a violation of Backman’s parole, raising the possibility that the Diamondbacks’ new manager would soon be in jail. (Backman said he hadn’t known he was on probation.) More fundamentally, the Diamondbacks felt Backman had a problem with alcohol that he refused to address and had been less than truthful with them.

When the Backmans sat down with Karl Taro Greenfeld for a 2005 Sports Illustrated profile, they doggedly went through Wally’s legal troubles point by point. There were a lot of points. Confronted with a fair-sized pile of paper, Greenfeld wisely stopped considering each tree to admit that he was in a forest. “It is impossible not to wonder,” he wrote, “how one man could generate so much paperwork.”

(An unwelcome sequel: In the summer of 2019, Backman was arrested after a fight with his girlfriend and accused of taking her phone so she couldn’t call the cops. The girlfriend turned out to have a fair number of skeletons in her own closet and Backman was cleared of charges, but the case sounded unhappily familiar, and put a bunch more papers on that pile.)

Backman started working his way back to the majors in 2007, returning to the independent leagues to manage the South Georgia Peanuts and splitting $40,000 in salary with three coaches. His comeback was documented in Playing for Peanuts, and a video of a miked-up Backman being ejected will live forever. And justifiably so: After berating umpires for tossing out one of his players, Backman litters the field with bats and balls, screaming, “Pick that shit up, you dumb motherfuckers!” (An oddly courtly moment in his tantrum comes as he pauses to warn the opposing catcher to get out of the way.) The bats and balls sit on the field, untouched to avoid another eruption, as Backman tells his ejected player they’ll go get a beer and then hunts for a clipper to deal with the fingernail he just split. The aftermath, though, was less entertaining: Backman heard that the Peanuts’ 22-year-old radio announcer had described his fit as an embarrassment and burst into the press box to berate him and threaten to shove the mike up his ass. Asked by Pearlman why he’d done that, Backman struggled for an answer and settled on “I have lots of pride.”

Still, five Peanuts got pro contracts — Backman hadn’t lost his touch as a baseball instructor. In late 2009 the Mets offered him a road back, hiring him to manage the Brooklyn Cyclones. When the team parted ways with Manuel, Backman was a finalist for the job in Flushing, but wound up in Binghamton instead. The big-league job went to Terry Collins — another fiery skipper who will live on in video legend. Backman moved up to manage Buffalo and Las Vegas, where he helped prepare Matt Harvey, Noah Syndergaard, Wilmer Flores and Brandon Nimmo for the big leagues. (Temperament aside, you can see some of Backman in how Nimmo attacks a plate appearance.)

Backman thought he was in line to be Collins’s successor, and there were fans who wanted him to be, campaigning at any sign of trouble for the old ’86 hero to show up screaming and overturning buffets. Except, well, when’s the last time you saw a manager do that? The game had changed, with front offices taking greater control of lineups and tactics and managerial duties becoming more about dealing with clubhouses and the media. Hell, Collins himself had changed, remaking himself from the high-strung skipper who’d burned out clubhouses in Houston and Anaheim into a far more even-keeled leader. (Well, OK, mostly.)

Was Backman still the right personality for the job he’d always wanted? I wondered. After one Las Vegas season ended, Backman was brought in as a September coach, and chose 86 as his number — the only time, I believe, that’s adorned a Met back in a regular-season game. It was nice to see, but also a little sad — because I had the feeling that was as close as Backman was fated to get.

At the end of 2016 Backman resigned under a self-created cloud, claiming he’d been forced out by Sandy Alderson and blackballed in trying to find a job with another organization. Was that true? Who knows? But by airing his employers’ dirty laundry, Backman did an excellent job of blackballing himself. He returned to the independent leagues, managing in Mexico, in New Britain, and then with the Long Island Ducks. There, this most old school of skippers found himself dealing with experimental rules, such as a prohibition on mound visits and shifts. His pitching coach, former teammate Ed Lynch, said that it was “like John McGraw dropped into the middle of our clubhouse.”

I’d be surprised if Backman ever gets the second chance he hungers for, but I’m not willing to concede that’s an injustice — that pile of papers is hard to unsee. But I find pleasure in his trail of managerial addresses, which could be transplanted to the back of a baseball card from the 50s or 60s: Mountaindale, Bend, Tri-City, Winston-Salem, Birmingham, Lancaster, Albany, Joliet, Brooklyn, Binghamton, Buffalo, Las Vegas, Monclova, New Britain, Islip. It’s a baseball rat’s pedigree — maybe not the one Backman wanted, but an honorable one I hope brings him some joy. And, in time, a little solace.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1968: Cleon Jones

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1980: Lee Mazzilli

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1985: Dwight Gooden

1986: Keith Hernandez

1987: Lenny Dykstra

1988: Gary Carter

1989: Ron Darling

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

1999: John Olerud

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Michael Conforto

2016: Matt Harvey

2017: Paul Sewald

2018: Noah Syndergaard

2019: Dom Smith

2020: Pete Alonso

2021: Steve Cohen

Most of the folks in this series are beloved, some are liked, and some are, well, meh.

So let’s get 1979 over with by highlighting a guy who hated being here, and who Met fans despised, to this very day, and to legendary proportions.

It’s Richie Hebner, of course, and that would be one fun read.

We’re down to 1979 and 2006, and while I don’t want to spoil anything, I doubt they’d be hard to guess. (I promise neither is from Jason’s List of Insanely Random Cup of Coffee Mets.)

He was a born instructor. He was a guest at my baseball camp in 82 or 83, and even at that age cranked out advice after watching us play for an hour. (His advice to me was dont hit with just your arms, use your size to your advantage.)

That’s awesome.

To me, Wally was the Everyman on that team. If that little guy could claw his way into the World Series, anything was possible.

Mike Lupica wrote an article in the mid-’80’s that I always remember. It was a flash forward to the early 2000’s. In this version, Doc Gooden had just notched his 300th career victory for the Mets, with his pal Darryl Strawberry contributing to the victory with yet another home run. And manager Wally Backman looking on with pride. Thinking about that article always makes me sad, for all three of them.

I loved Wacky Ballman — he, Dykstra, and Knight were so much of that 86 team’s personality. Shame it didn’t lead to more championships.