Every fall, the postseason brings three individual awards: the NLCS MVP; the ALCS MVP; the World Series MVP. I inevitably stay tuned after championships are determined to find out who won each respective series MVP, never thinking that it’s odd that a prize is about to be presented for a performance spanning as few as four and no more than seven games. Likewise, I always hang around to learn who the MVP of the All-Star Game is, and that is literally about how well somebody did in just one game — a game that doesn’t count (and a game in which almost nobody plays the entire game).

This all seems normal behavior in the realm of baseball fandom, yet when the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee commenced to contemplate who would receive the coveted Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met award for 2020, FAFIFAC paused. The Mets, as you know, played a sixty-game season this year, more than a hundred games off the norm. Ascertaining value within this smallest of full-season sample sizes struck the committee as an exercise doomed to incompleteness. Was that really a season? And, other than having something new to watch on TV sixty times, was there any value in it?

The Baseball Writers’ Association of America signaled yes and yes, as the BBWAA gave out all its usual MVP, Cy Young, Rookie of the Year and Manager of the Year awards in November despite the absurdly low totals it was determined to recognize. That the season didn’t feel quite authentic was beside the point. It was called a season. Players played in it. That, apparently, was enough.

After months of delay and doubt, we had what we agreed was a 2020 Mets season. But was there “Most Valuable” value demonstrated by any of the 26-34 Mets? Far be it from us to dismiss a sub-.500 team from the realm of individual praise. FAFIFAC renamed its MVM in honor of Ashburn in 2017 precisely because Richie was chosen by beat writers in 1962 as the Original Mets’ MVP. Ashburn was a touch bewildered by the designation — “Most Valuable Player on the worst team ever. Just how did they mean that?” — but in our minds, a precedent was set. No Mets team is so bad that you can’t say somebody hadn’t stuck out as good…or at least stuck around, and that was good. Maybe, then, we can say that no Mets season is so brief that somebody doesn’t accomplish a few things that deserve lasting recognition.

What’s inescapable, however, is the lack of length prevented a traditional course of MVM events from emerging. There was no palpable first half or second half. There was no stretch drive. There wasn’t a long enough haul from which a single Met could truly emerge as vital or triumphant or a model of perseverance. There were just sixty mostly messy games plopped onto a shapeless grid of a semi-schedule sanctioned seemingly for the amusement of corrugated cutouts. Within this bizarre atmosphere, the Mets never really got going. They just got gone.

But FAFIFAC likes to give out its awards, so it will, but with a caveat: this was quite obviously no normal year, so we are presenting here not the normal Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met award, but, for 2020 (and hopefully never again), the RichAshes: truncated trinkets for what proved a disposable seasonette. We still sincerely salute our winners, we’re just sorry they didn’t get a fuller chance to totally show their stuff.

True, had 162 games been played, maybe some other Met would have come along and surpassed them in our estimation, but we’ll never know. We only know what we experienced in 2020. Most of it wasn’t worth preserving let alone cherishing. But what these guys did wound up more than a little cut above the rest.

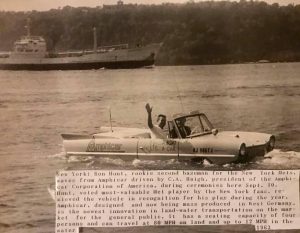

Prelude stated, the RichAshes of 2020 go to Michael Conforto and Dom Smith, co-MVMs in a compressed context. They individually made the most of the Mets’ limited run and were, together, the most compelling reason to keep tuning in nightly, even when shtickless stalwart for all seasons Jacob deGrom wasn’t pitching. If we could, we’d give them each their very own Amphicar, just like the one Ron Hunt won as sole MVP on the 1963 Mets. But since they’re reasonably chummy to begin with, we’d like to imagine they’d happily share one, given that Amphicars are tough to come by these days.

The Smith-Conforto combo seems a most appropriate choice when considering each enjoyed a particularly scalding chunk of baseball when either could have been on his way to traditional Ashburn honors. For a while, Michael Conforto looked like NL MVP timber for any season. Perhaps it was because the Mets never legitimately contended — and probably because elite offense ran rampant practically everywhere — no BBWAA voter officially noticed a batting average of .322, an on-base percentage of .412 and a slugging percentage of .515. The shadow cast by the onslaught of hot-hitting Braves, Padres, Sotos and Mookies blanketed any attention Conforto might have gotten, and Michael received no votes for league MVP.

On the other hand, Dom Smith hit so much that the writers had to mark their ballots with pens containing thimblefuls of orange and blue ink. After riding the bench on Opening Day, Dom started starting and making the most of his opportunity. The slash line of .316/.377/.616 is not only impressive to the naked eye, but it represents a sizable jump in every category over anything he posted in previous years. Smith’s 10 homers in 50 games nearly matched his 2019 total of 11 launched in 89 games. The voters noticed, placing Dom 13th in the MVP race, the only Met to garner any support and pretty good for a team whose offensive noise didn’t amount to much in the way of winning.

The most recent set of Mets consolidated as a strange collective creature when it came to batting. Remember how they started the baseball portion of 2020? They were putting runners on by the baseload but had a hard time shaking them loose from first, second and third — particularly second and third. Here are some of their in-game RISP performances as the season got going:

July 26 — 1 for 8

July 29 — 3-for-14

July 30 — 1-for-10

August 1 — 1-for-10

August 2 — 1-for-15

Not surprisingly, those were all losses. After stranding oodles of runners in scoring position, the Mets fell to 3-7 and never really recovered. Eventually they began to drive one another in with a little more regularity, yet an offensive rhythm eluded them. Consider that when it came to leaguewide OPS+, the metric designed to factor ballpark conditions into combined on-base and slugging percentage, the NL East champion Atlanta Braves placed fourth; the top Wild Card and holder of the second-best overall record Slam Diego Padres placed third; and the eventual world champion L.A. Dodgers placed second. Who did all those juggernauts look up to in this presumably very telling category?

The also-ran New York Mets, whose 122 OPS+ topped the senior circuit. Yet who came in seventh among total runs scored, well behind the Dodgers, Braves and Padres? Those same New York Mets, whose 286 runs checked in just slightly above the league average.

When the Mets didn’t drive in runs, from whatever base, the hole they left in their wake was gaping. But when they did score, they seemed to do it in gobs — in one of every ten games, they scored in double-digits; in three of every ten, they scored at least seven — and when the Mets scored gobs of runs, it was Michael and Dom doing much of the gobbling.

Runs created is a measure originally crafted by Bill James to gauge just how effective all the hitting a given player is in…well, creating runs. “To put runs on the scoreboard,” the godfather of modern advanced statistics posited, is the whole idea of getting on base, never mind slugging. Best among the 2020 Met run creators were Smith and Conforto, each weaving 42. In the realm of weighted runs created plus, or wRC+, which has nothing to do with RC Cola but everything to do with external factors like ballparks and overall league performance, Conforto (13th) and Smith (19th) were, by FanGraphs’ reckoning, the only two Mets to land in the NL’s Top 20.

In traditional and perhaps more easily digestible numbers suitable for the weekend after Thanksgiving, Dom finished tied for fifth in RBIs in the National League; Michael was seventh in hits; Smith finished second in doubles behind only MVP Freddie Freeman; and Conforto came in sixth in singles. Conforto’s OBP ranked sixth, while his batting average placed seventh. Smith was tenth in batting average, fourth in slugging. They were both Top Tenners in adjusted OPS+, with Dom in fourth and Michael in tenth.

Dom’s ability to hit for extra bases — 32, most for anybody in the league except for Freeman — stands out even more in light of his not having a position when the year began. Even with the National League giving in to peer pressure and sinfully adopting the designated hitter, a batting order slot specifically designed for a fellow who is more stick than leather, Smith had to sit. Yoenis Cespedes was still around, and the 2020 version of Cespedes was judged not physically capable of patrolling the outfield, where he’d once won a Gold Glove, thus his salary got priority at DH. First base, Dom’s natural habitat, was filled as far as the eye could see by a Polar Bear named Pete. Dom as a left fielder has always had a tough time being taken seriously. As he had in 2019, the man had to wait his turn.

Fortunately, it didn’t take long for Luis Rojas to ascertain a sitting Smith wasn’t nearly as useful to the cause of winning games as one who is depended on regularly. By the second weekend of the season, Yo wrote his ticket out of town by not showing up at the ballpark in Atlanta (and not saying anything to anybody about it until he cited COVID concerns). Suddenly, Dom was a born DH…except, wait a second, he was actually a born first baseman when he was drafted in the first round by the Mets in 2013. Sure, Pete Alonso had marked his territory with his Rookie of the Year/MVM tour de force in 2019, but 2020, as if anybody didn’t notice, was a totally different year. Though Smith was capable of taking reps in left field, more and more we saw Dom back in the infield, starting fourteen of sixteen games at first at one point. His hard-earned versatility reveals itself in the sum totals for the year. Dom took 22 starts at first base, 21 in left field and, perhaps surprisingly, just five as DH, with none of those over the final forty games. It was Alonso (17 designated hitter starts) who had to scoot over to make a little defensive space for Smith.

Where Conforto would play was no more mystery than whether Conforto would play. Michael was a mainstay in right field from Opening Day forward, at least until a hamstring injury ended his season a week early. A corner seemed to have been turned at last in 2020 for the Mets’ top pick of 2014. No one was any longer shifting him to center or left or much questioning his defensive dexterity. No one was proffering trade proposals out of disappointment or impatience with him. Everyone was wondering how soon the new owner would get around to extending him beyond his final year of team control, which arrives next year, one year after Conforto’s must-sign status became universally apparent.

It constituted a bonus to take stock and realize that the Mets’ top selections from back-to-back drafts (chosen by Sandy Alderson, no less) had blossomed in unison. Smith had been picked a year earlier, but Conforto beat him to the bigs by a couple of seasons. They’d each bounced up and down quite a bit. In 2020, though, Michael put together an essentially slump-free season just as Dom was morphing into a vital Met regular. Everything you hoped they could do, they were doing. Everything you weren’t sure they were able to do, you stopped worrying abut. It was a short summer and the quickest of falls, but it was nonetheless a season for coming of age for these maturing teammates. We’re no longer doubting all Conforto can do; we’ve stopped being wary of what Smith can’t do. We’re content to let them play, let them field, let them hit…and we trusted them on one occasion when they let us know maybe the game itself wasn’t the most important thing for the Mets to worry about.

Dom Smith motivated the Mets and their opponents the Marlins to step back from the field on August 27, one night after Dom took a knee during the national anthem out of anguish for what had occurred in Wisconsin. A Black man named Jacob Blake had been shot by police in Kenosha. It wasn’t too many weeks after the life of a Black man named George Floyd had been ended in the name of law enforcement in Minneapolis, an episode that set off protests across the nation. That wasn’t too many weeks after a Black woman named Breonna Taylor had been shot to death by police in Louisville. Floyd and Taylor, like Blake — and Smith — were Black. These surely weren’t the first three times or only three times the existential American question of whether Black lives truly mattered to those in authority was on the table. One would have thought the matter was self-evident, what with everybody being human.

Nor was it the first time that the question came to the arena of sports. Blake’s shooting was too much to bear for his home-state Milwaukee Bucks, and they decided that even isolated in a “bubble,” they wouldn’t play their NBA playoff game on August 26. Sports, never wholly separate from the world in which they are contested, felt the gravitational pull of events. It compelled Smith to silently, peacefully drop to one knee during the ritual playing of The Star-Spangled Banner prior to the Mets-Marlins game that night. Smith was noticeably the only Met to take a knee. Forced by external albeit familiar circumstances to take notice of larger issues, he was also the only African-American player in the Mets starting lineup that night. With Marcus Stroman having opted out for the season because of the pandemic, Smith started and ended 2020 as the only African-American player on the Mets’ active roster; Billy Hamilton joined the Mets in early August but lasted only about a month.

When you watched the Mets in 2019, especially when they came on like Natbusters in the second half, you were taken by their togetherness. They were Mets and they pledged to each other their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor. Technically, those words are from the Declaration of Independence, but experiencing the Cookie Club vibe from the summer before and through video check-ins during baseball’s hiatus, you believed these guys would stick together through thick, thin and everything in between. These two guys in particular were still, if we filtered out everything else, at the core of a fun crew of Mets answering to silly clubhouse nicknames (“Sloth Bear” for Smith; “Silky Elk” for Conforto). Thus, when you watched Smith kneel alone in 2020, it was discomfiting on multiple levels. I can’t say I know what it feels like to be a Black person in America and have to have it restated repeatedly for a general audience that your life matters until the thought doesn’t come off as controversial, but I do know what it is to be a Mets fan, and I saw one of our own alone out there on the 26th of August. I knew that felt wrong.

Smith, who’d been moved to his gesture by the Bucks and others in sports, wasn’t necessarily looking for company. In his postgame remarks, he said what he’d done was “not for them,” meaning his teammates. He had to do it in the moment. But he also wasn’t taking a knee in a vacuum.

“I think the most difficult part is to see people still don’t care,” he said through tears that night. “For this to just continuously happen, it just shows the hate in people’s heart…and that just sucks, you know? Black men in America, it’s not easy…”

Dom had played despite acknowledging his mind had been elsewhere. The next night, none among the Mets nor Marlins played. While the joint statement that transcended MLB’s usual attempts at performative empathy — both teams lining up for 42 seconds of silence; draping a Black Lives Matter shirt at home plate; departing an even quieter than usual 2020 Citi Field after not playing ball — wasn’t solely Dom’s doing, it was his display of genuine angst the night before that set the stage. And, for what it’s worth (and I think it was worth plenty), it was Conforto, as the Mets’ Players Association representative, who negotiated the symbolism and logistics with his Miami counterpart Miguel Rojas. The night before, Conforto had said of Smith, “His world is much different than mine. So it’s definitely helped me to listen and understand where he’s coming from and where a ton of people are coming from here.”

Within 24 hours, Michael developed a better idea of Dom’s perspective. “It really touched all of us in the clubhouse, just to see how powerful his statements were, how emotional he was,” Conforto said on the 27th. “He’s our brother, so we stand behind him and we stand behind Billy. All the players who stand up against the racial injustice, we stand behind them. And that’s what you saw tonight.”

What we also saw was, in the press availability that followed the Mets and Marlins proactively postponing their game, were Conforto and Smith standing together, alongside veterans Robinson Cano and Dellin Betances, to embody the Mets’ unified front. “It’s still overwhelming at this moment,” Dom said after the two teams voted to not play, “just to see how moved my peers are, my teammates, my brothers, the front office, the coaching staff, everybody who talks to me on a daily basis. Just to see how moved they were, it made me feel really good inside. It made feel like we are on the right path of change.”

It was just one night in a season that didn’t have nearly as many nights or days as usual, and it was surely as unusual a night as one could absorb viewing a ballpark’s activities from afar. Maybe it wouldn’t have happened or been so meticulously scripted had this been a season with a ticket-buying crowd filing into the house. The differences between 2020 and all years before it cannot be stressed enough. Then again, the issues that got to Dom were issues that had been present in his life and his nation’s life for too long. It wasn’t as if the phrase about Blacks’ lives mattering was invented this year. Perhaps the right path of change is indeed being pursued, even as way more needs to be done. Perhaps there’s only so much you can ask of a couple of ballplayers in their twenties to do about changing the world, particularly when the schedule has them going back to being ballplayers playing ball the next night.

We hope for a lot of things in this world. Dom Smith and Michael Conforto are Mets who make you believe that once in a while your hopes don’t go for naught.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez (original recording)

2005: Pedro Martinez (deluxe reissue)

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

2019: Pete Alonso

Still to come: The Nikon Mini Camera Player of the Year for 2020.

Well done Greg, and an excellent choice for co-MVP’s, tied into what for me was the most memorable event of the most bizarre and disorienting Mets season.

Long story short, month or two ago, I went to pick up a pizza wearing one of my Mets masks. Owner introduces me to another customer, saying “You’re both Mets fans.” At which point this other guy says “Well, I was until they walked off the field. Never again.” So in other words, he wasn’t a Mets fan. Never was. He and I did not have a friendly conversation.

I just hope Dom did not take any “advice” from Cano.

Well, as I said at the time, I didn’t agree with Dom’s (or the Mets’) actions vis-a-vis BLM, and I believe that over time I will be proven right. I also said (and still believe) that Dom is certainly entitled to his opinions, as this is (for now) a free country. Maybe one day we will all remember how to disagree without being disagreeable, to defend to the death the other guy’s right to say things you believe to be wrong, etc etc. May that day come soon.

Having gotten all that out of the way, I wholeheartedly endorse both of your Ash(burn) picks this year. Dom is the first guy I’ve ever seen to un-Wally Pipp himself and put young Gehrig in his place. It’s pretty inspiring. And as for Mr. Conforto, he may well come to be seen as the ultimate survivor of Wilponism. Sign him now, Steve, before it’s too late. You won’t be sorry.

Next year in this time slot I hope to see another first-time winner…

Trevor Realspringer!

…

Hey, one can hope…!

Greg,

Powerful entry and one of your best (among many) in a year marked with extraordinary grief, disappointment, and bizarreness. Yet, now there’s hope. I carry hope for a better future led by a new generation of young men like Dominic and Michael together with their bold, female counterparts, athletes or not. People of character deserve recognition so the public may be inspired and emulate their actions. It is so fitting how you wove these two Mets into the story of the most valuable, both as players and as leaders. Watching Dominic tear up with raw emotion about the risk Black people face every day, just for being Black, brought me to tears as well. Hearing him relate to Steve Gelbs (in that SNY special interview) how he was harassed by other drivers and cops in Port St. Lucie, how he and JD Davis were not served at a PSL restaurant despite waiting patiently for two hours, and other injustices, only underscores how pervasive the problem of hate and racism still is in our country. So many parts of America need to change–now. I don’t get how not everyone sees this.

Wilmer Flores’ tears are not the only impactful ones from this decade of Mets. Those came in a season a lot more enjoyable, a lot longer, but the tears of Dominic Smith may be even more significant in the long run. I was proud it was him, front and center among MLB in speaking out for justice, and, as a Met fan, I was proud it was a Met who did this most important representation. Props to him, to Michael, and all their teammates and organization professionals who brought their message to the fore.