This time his observations were outrunning his understanding. This vague America he was now reporting was swelling with strange, vague forms which his thinking could no longer shape into clean stories. No piling up of more reportorial facts, no teasing anecdote, no embracing concept, could hide from him what was wrong: his old ideas no longer stretched over the real world as he saw and sensed it to be. Thus, as the campaign wore on, he found himself more and more bewildered. How had America come to this strange time in its history, and he with it?

—Theodore White, In Search of History, 1978

Ah, good old familiar baseball, especially its tension and drama. It’s timeless. Can’t ya just picture it?

It’s the last inning, meaning it’s ninth inning.

Unless there’s another game scheduled, in which case it’s the seventh inning.

Let’s just say it’s the last inning, whichever it is, unless there’s an extra inning, in which case we’ll play a tenth.

Or an eighth.

With a runner on second before anybody bats.

If it’s the bottom of the inning, at least we know the home team is batting.

Unless hastily cobbled rearrangements dictate that the visiting team is batting last.

Pitching is whoever was pitching for the previous two batters, no matter what, basically.

Batting ninth for whichever team is hitting is likely whoever was batting ninth all game long, and certainly not because their pitcher is pitching a complete game.

Warming up in the pen, however, could be just about anybody these days, and somehow anybody will eventually come in.

It makes ya wonder who might be doing what in the minors — wait, are there still minors?

Anyway, whatever play is made here will get no reaction from anybody in the stands, because they are literally a bunch of stiffs.

Yet there sure is a lot of crowd noise.

Maybe whoever’s up in the broadcast booth can make sense of this…provided they’re up in the broadcast booth of the same ballpark in which this game is being played.

Whatever happens in this inning, the key thing here is we still have a chance to be one of the…how many teams make the playoffs again?

Thanks, baseball. You’ve got me on lawn patrol at last. Get off mine with your changes nobody invited.

Admittedly, I’m veering into Crotchety Old Columnist territory here, and I’m about to ramble a bit, as a person who’s not meaningfully interacted with people outside of a screen, a phone or a doctor’s office very much for many months might, but I assure you my kvetching emanates from a place of authenticity. As much as I comprehend the desperate contingency that went into creating a sixty-game schedule gussied up with atonal bells and off-key whistles, the parts that masqueraded as progress made feel something in 2020 that I never before felt quite so acutely in my 52 seasons as a baseball fan. I felt estranged from the game I love. The stubbornly timeless game had a surfeit of change shoved down its throat to a point where even if I could recognize it as essentially the same game that captivated me in my youth, it became more difficult than ever to engage it on the same level where I’d embraced it for decades.

The season was too short. And the games dragged on too long. Somewhere within, emotions trembled, but not often. Maybe not until the end. On suddenly arrived Closing Day, SNY reran the tribute video the Mets produced after Tom Seaver died. I teared up. When the game was over, credits rolled over a montage of cheering crowds from 2019. Not the players, just the fans. That made me tear up more. Soon after, the club e-mailed out its annual thank you video, with highlights from the season just concluded. In the background, I saw empty seats and cutouts.

Tears turned to dismay. Distance returned. Go away, 2020 season. Keep going, please and thank you.

In late July, baseball came on television again [1] after several months of sensible absence. I attempted to process it, interpret it, absorb it and generate passion to want more of it. It only partially took. That went for Mets baseball as much as it went for all baseball. The result made me yearn for the replacement of Rob Manfred as commissioner with Paulie from Goodfellas. I yearned to hear Paul Sorvino’s boss of a character giving it straight to MLB about what to not do next:

I don’t want any more of that shit…just stay away from the garbage, you know what I mean…I’m not talkin’ about what you did inside. You did what you had to do. I’m talkin’ about now. Now, here and now…don’t make a jerk out of me. Just don’t do it. Just don’t do it.

I suppose I’m preternaturally resistant to change, but during the 2010s, I came to see the wisdom of baserunners not slamming into catchers. I like the idea of video replay review if not the logistics. Middle infielders as targets should have gone out long before Chase Utley came along. I don’t hate the Wild Card. I’m fine with new, hopefully enlightening statistics entering our general conversation. Tradition flecked with progress keeps tradition fresh. Yet there was nothing about the 2020 baseball season that wasn’t around in 2019 (give or take Andrés Giménez) that I wished to pack up and ship ahead in care of 2021.

I’m going to project a little here and decide I can’t possibly have been the only one to have experienced such a “this is not my beautiful game” disconnect, and I’m going to declare the Nikon Mini Camera Player of the Year award — dedicated annually to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates or transcends the year in Metsdom (amended this year to acknowledge how briefly the campaign ran) — belongs to the sensation of Distance. Reaching out and touching someone was a bad idea if you wanted to stay well. But not being able to get a feel for the thing you were certain you knew?

So far away. Doesn’t baseball stay in one place anymore?

Distance, whether expressed in terms social, physical or mental, was an overriding fact of 2020 life, imposed with the noble aspiration of avoiding more 2020 death. Don’t stand so close to me. Or me. Or me. Nothing personal. We get it and we got it in the hopes that we wouldn’t catch it. It would be disingenuous to say the least strange element of baseball this past year was that it was played without fans in the stands in deference to COVID-19. It was awfully strange, yet to have baseball at all was to understand the isolation of players and coaches from the rest of baseball’s usual citizenry had to be baked in. Little media. Skeleton staff. Zero spectators. Play ball?

We can be as adaptable as phonographs when we have to be, and after a while, baseball played in front of empty seats disguised as fans seemed provisionally normal. When the neutral site doors of Globe Life Field in Arlington were opened to a capped quantity of ticketed customers for the NLCS and World Series, and the biggest games of 2020 were played in front of a quarter-full house, the weird part was having anybody at all on hand — and their hands high-fiving, presumably sans sanitizer.

The ballpark-as-studio conceit was as eerie as it was necessary. Getting used to it was likely more depressing than encountering it (from a distance) the first dozen or so times. It wasn’t so much that I missed being at games. I missed anybody being at games. Jacob deGrom leaving the mound after striking out 14 in his final 2020 start [2] should have received a standing ovation. But corrugated cutouts, whatever they’re made out of, are notoriously unresponsive.

But, again, per Paul Cicero, they did what they had to do, assuming we had to have baseball, as if it delivering it to us was an essential service. Having had it, I can’t say it wasn’t better than having none at all. On the other hand, I had resigned myself in March to not having any and was going along relatively fine without it. I had my share of Tuesday/Friday essays [3] to occupy my Met muscles. I had a fairly fresh passel of Mets Classics on SNY. I had a half-century of Mets baseball coursing through my brain. What was I missing exactly? The chance to obsess over whoever the Jason Vargas of the 2020 Mets was going to be?

“The thought crept in,” Teddy White, the author of four Making of the President books, acknowledged to himself [4] when he realized he didn’t quite have it in him to go out on the road and make a fifth, “it was probably more useful to go back than to go on.”

But we went on when baseball said it could, when the public health forecast was looking up, or at least across, so I went along for the virtual ride, the one with…

• the DH invading the National League (a vile experiment the AL neglected to unplug in 1973);

• the doubleheaders with seven innings apiece;

• the runner magically appearing on second base to start each extra half-inning;

• the shuttling in of mysterious characters from “alternate sites”;

• the looking live at Citizens Bank or Nationals Park with the voices of Gary, Howie and their cohort reporting live from Citi Field;

• the seeing plenty of the Rays and Jays with no glimpses of the Padres or Pirates;

• and the corrugated cutouts frozenly cheering the whole deal on.

Compared to all of that, pushing a shopping cart while wearing a mask and having to wait six feet from the customer ahead of me at checkout was perfectly normal.

Not everything about baseball in 2020 was a product of attempting to avoid a potentially deadly virus. They were ready already to mess around with relief pitching, with the constraining three-batter rule previously sketched out. They were ready already to take an axe to the minors and kill off dozens of affiliates [5]. Too many strikeouts and a proliferation of home runs didn’t materialize with the turn of the decade. Yet within the eerie confines of the empty ballparks, even the distant home runs felt cheap, and the thrills they were intended to give us felt distant.

And no matter what they did, the relatively regulation games dragged into perpetuity. I think the Mets are still playing the Braves from a few month ago (it’s the bottom of the sixth).

This baseball season, even while in as much progress as it could muster, felt uncommonly far away. It was removed from looking like, sounding like and feeling like the game we fell in love with. Certainly the game I fell in love with. If I were a conspiracy theorist, I would theorize baseball was conspiring to detach me from baseball. Take the DH (please) for example. The arguments for endorsing it as its fulltime adoption probably grows inevitable are becoming ubiquitous in our neck of the woods mainly because we have two power-hitting first basemen. Will getting a few swings out of Pete Alonso without sending Dom Smith to left or the bench benefit us? Often it will, I imagine. Will the designated hitter also help some other team with excess boppers and a finite number of defensive outposts and might it help them, to the hindrance of our pitchers? Most coins have at least two sides.

But never mind the transactional component. I won’t even play the “strategy” card, even though, yeah, there is some thinking that’s missing by not having deGrom on deck in the sixth or seventh of a tie game. What I discovered I really disliked about the DH was it unhinged the tops and bottoms of innings from one another. Here’s the game where the Mets are batting. Here’s the game where the Mets are in the field. They don’t meet in the middle. The flow is disrupted. The action is unmoored. There’s a game where we bat, there’s another game that takes place in an inset, like a pitcher-in-picture. It’s not what a pitcher does while batting that I miss. It’s that the pitcher bats at all. It’s that the pitcher isn’t off conducting his own game apart from his teammates. Call me old-fashioned. I like my team presenting itself in unison. If the manager doesn’t want the pitcher to bat, pinch-hit for him and bring in a new pitcher.

On the other hand, stop bringing in so many pitchers so soon. Let starters extend themselves long enough to make their at-bats an issue. Your bullpen will appreciate the breather. Your viewers will appreciate the continuity. Reliever after reliever — even with the manager being told he has to stick with one reliever until he has a third out in an inning — takes its toll. Arms get weary. The roster-replacing gets dizzying. You couldn’t tell the players without a scorecard in a year when nobody printed any. The Mets needed 25 pitchers to win 26 games and lose 34 of them. And two of the pitchers were position players.

If keeping track of the 30-, 28- or whatever-it-was-man roster on a given day was difficult for the team a fan followed, it would have taken a data dump worthy of Statcast to have a handle on who was elsewhere in the majors, especially in a season when it was decided (not illogically) that the COVID environment wasn’t suitable for loads of travel. So the Mets played their own division and their geographic counterparts in the AL East. Even if it was reasonable, it was another cause for detachment.

There was a Sunday in September when I learned a Cub was pitching a no-hitter. I tuned to MLB Network to see if the pitcher would get it. I realized I didn’t recognize the pitcher (Alec Mills), and that the batters he was facing on the Brewers were 2020 strangers. I hadn’t seen either of these teams play the Mets, which meant I hadn’t seen either of these teams play at all. One of the satisfactions of a regular season is the tour through the league’s opponents. What’s new with L.A.? San Fran? Cincinnati? And so on. The Central and the West were rumors and the occasional highlight.

It would take the arrival of postseason to see some teams that didn’t play in the Easts, yet October left me as cold as anything else. Teams I didn’t know playing in vacant lots, with lots of synthetic noise and those damn cutouts. I mostly skipped the tacked-on first round. I tried to involve myself in the LDS as an October tourist, the way I always have, getting caught up in somebody else’s storyline for a couple of weeks. It didn’t really take, save for being happy the Yankees stopped being involved. I rooted for the Rays to beat the Dodgers in the World Series. The Dodgers, whom I’ve reflexively despised since Utley brutalized Ruben Tejada [6], won. I shrugged.

Eight playoff teams per league. Neither league’s playoffs encompassed the Mets. Can’t blame 2020 for that, but it’s not a feather in the year’s cap, either.

First off, I’m still here. I wasn’t going anywhere. It would take a lot to altogether turn me off. That’s not a dare to Rob Manfred, mind you, but it’s a fact. Baseball’s got the Mets. I can’t quit them, as illustrated by this conversation between my wife and me one weekend while the 2020 Mets were playing and losing:

“This team gives me such a headache.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t watch them.”

This is usually where I would scoff at such a curative notion. Instead, I insisted, “I’m pretty close to not watching them!”

Then I went back to watching them, with a headache. Eventually they lost. After thorough disgust had overtaken me, I needed a shower. I went to grab a clean t-shirt. It was a Mets t-shirt. I flung it on the bed and remarked how this was not the cause I needed to represent at this moment. My wife helpfully suggested I could pick another shirt from my drawer, as I do have a few that aren’t inscribed with the Mets wordmark or logo.

Nah, I said.

Granted, it wasn’t much of a rallying cry, but, nah, I wouldn’t think of not representing the orange and blue, even if it’s only in quarantine.

A few days after the World Series, there was definitive word that our team would be run by a new owner, a Mets fan who didn’t have to pick and choose among free agent targets. Dismounting the carousel as the Steve Cohen Age kicks in would be self-defeating. Not that I’d be exiting even if one Wilpon was leading to another Wilpon, which was what I thought it was always gonna be. Granularly, I didn’t feel 2020. But in the great journey through Metsdom, my path’s end point defies distance. I don’t believe it’s out there. Lately I might’ve had my fill, but I feel it still [7] (just let us kick it like it’s 1986 once in a great while).

When Cohen was announced as on the verge of taking over, the date was October 30. Instinctively, I assumed it was March. Man, I thought, I could really go for some Spring Training right about now. If eighteen years of sole Wilpon control — with the eighteenth of them shapeless, rhythmless and no more than semi-relatable — couldn’t douse the embers of my childlike enthusiasm, chances were they could only be stoked.

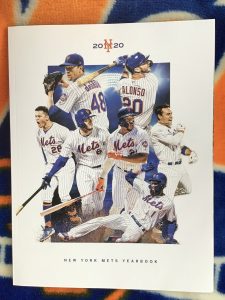

Then there was my yearbook. My 2020 yearbook. As noted above, you couldn’t buy a scorecard or even pick up a pocket schedule, but the Mets did print some yearbooks. They put them on sale via their Web site and offered to ship you one if you really wanted to buy it.

I really wanted to buy it. The desire wafted in on a breeze from 1972, the year of my first yearbook, the year before I first went to Shea, so I had to send away for it, to 123-01 Roosevelt Avenue, Flushing, NY 11368. It costs quite a bit more than it did back then, but it’s not prohibitive. I pick one up every year at Citi Field even though there is less and less content worth ponying up for. I leaf through it on the train ride home. I leaf through it a couple of more times once I get home. Then it lands on my pile of checked boxes. Like playing those teams from the other divisions, having the yearbook is just something that makes a season complete.

My 2020 yearbook came to me, just like the Mets said it would. It still has no content worth savoring. Some nice four-color photography, as Bob Murphy might have touted, including from early in the 2020 season (a.k.a. late July). No text beyond the basics. No special sections commemorating anything. Just pretty pictures and compulsory corporate cheerfulness.

This I savored. I savored having it in my hands. It had been accessible via download for a while, but leafing through it on an iPad wasn’t the same. That was just more distance. This was something to have and hold. This was the Mets in one bound volume, like the Mets of any year. Sometimes you just want something tangible [9] to remind you that something is or was real. True, there were players featured who barely existed in the present tense, players I’d all but forgotten since summer turned to fall. Brian Dozier [10] had a page. So did Eduardo Nuñez [11]. And what piece of official Mets propaganda would be complete without a straight-faced salute to Jed Lowrie [12]?

They were all there, and I was happy to see them where they belonged.

Knock scientific wood, we’ll get through the pandemic. We’ll get a vaccine, we’ll get inoculated, we’ll cease being so careful of getting in each other’s way and maybe we’ll get out to the old ballpark. Of the many items on Steve Cohen’s punch list, I hope, is the elimination of the stupid rule about bringing in backpacks or any bag remotely considered a backpack. It should be way down his list, but now that Trevor May [13] has been signed [14], maybe bag policy climbs a notch. (My brief scouting report on Trevor May: he’s just a couple of smart moves away from being an anagram for Mayor’s Trophy.)

I’d all but forgotten that I had to adjust my routine [15] in 2019, that I couldn’t carry my schlep bag, that I had to dig out a tote bag instead. It occurred to me during what little 2020 season there was that I wasn’t certain where my game tote bag was. Surely it was under a pile of stuff — and it was — but even once I found it, would I remember that I was supposed to take it with me the next game I go to? Would I remember how to go to a game? The getting on a train, the getting off a train, repeating the process until it got me to what is now called 41 Seaver Way, the approaching the entrance, the stiffening up prior to being searched (get rid of that, too, Steve).

Can you imagine, in 2021, going out to a game? Going out to a Mets game? Being that close to the Mets and Mets fans again so soon?

I’m still working on it.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS NIKON CAMERA PLAYERS OF THE YEAR

1980 [16]: The Magic*

2005 [17]: The WFAN broadcast team of Gary Cohen and Howie Rose

2006 [18]: Shea Stadium

2007 [19]: Uncertainty

2008 [20]: The 162-Game Schedule

2009 [21]: Two Hands

2010 [22]: Realization

2011 [23]: Commitment

2012 [24]: No-Hitter Nomenclature

2013 [25]: Harvey Days

2014 [26]: The Dudafly Effect

2015 [27]: Precedent — Or The Lack Thereof

2016 [28]: The Home Run

2017 [29]: The Disabled List

2018 [30]: The Last Days of David Wright

2019 [31]: Our Kids

*Manufacturers Hanover Trust Player of the Year