Tom Seaver idolized Hank Aaron [1] — “my hero in baseball from the time I was old enough to recognize talent.” Why would the future best pitcher in baseball gravitate to a hitter? “It must have been his form that made me pick him,” Tom wrote (with Dick Schaap) in The Perfect Game. “He seemed so graceful, such a complete professional. You could see the power in him, the strength in his hands and wrists. I sat through entire ballgames, just looking at Henry Aaron, nothing else, fascinated by him, studying him at the plate and on the bases and in the field.”

That was one of the first biographical notes I learned about Tom Seaver, whom I idolized. I guess that made Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves my grandidol. If he was grand enough for Seaver, that was good enough for me. Except I didn’t really need Tom Seaver’s blessing to admire the hell out of Hank Aaron. I was a kid who fell in love with baseball as the 1960s turned to the 1970s. Hank Aaron stood at the sport’s pinnacle. If you loved baseball, I don’t know how you couldn’t have revered Hank Aaron.

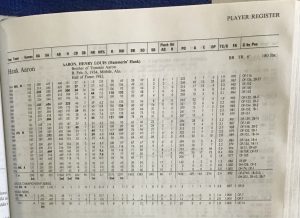

Or Henry Aaron. I learned because of Hank Aaron that “Hank” was short for “Henry”. Hammerin’ Hank. Bad Henry. Both fit, as did his last name: Aaron, first in your Baseball Encyclopedia for as long as you relied on the Baseball Encyclopedia when you wanted to look up baseball information…and where else were you gonna look up baseball information in most of the latter portion of the twentieth century? Alas, Henry Aaron’s been surpassed alphabetically in the twenty-first, just as the Baseball Encyclopedia has been technologically, so now he comes in behind David Aardsma [3] when you visit retrosheet.org.

He was surpassed in number of career home runs, too, but rather than serving to diminish his standing, Barry Bonds blasting a few more homers than Aaron only enhanced the status of the man listed as runner-up since the summer of 2007 [4]. Hank/Henry looks just as impressive in the Internet age as he did when we relied on the backs of baseball cards and the screens of portable black & white televisions for our glimpses of greatness. When some other medium comes along that allows us to absorb performance and persona, Aaron will still be right there at the top.

Hank Aaron died today [5] at the age of 86. Baseball Hall of Famers have died at an alarming rate of late. Seven last year [6], including Seaver (Aaron’s selection for “the toughest pitcher I ever had to face”). Three here in January. Tommy Lasorda [7] the celebrity manager early in the month. Don Sutton [8] the doggedly competitive pitcher early in the week. And now Henry Louis Aaron, as magnificent a baseball player and monumental a baseball person as has ever lived.

If one of the inner-circle superstars of the sport could be said to have snuck up on his crowning statistical glory, it was Aaron. Before he was one of the absolute greatest, he was one of the absolute greats. Hank Aaron kept a pied-à-terre on league leader cards. His summer vacations had to be deferred because he was inevitably needed at the All-Star Game. It was all very excellent and relatively quiet. For a dozen years his campaigns had been conducted in Milwaukee, where there were two World Series and an MVP award in the ’50s and moving vans lined up at County Stadium by the end of 1965. Then it was off to Atlanta. Aaron’s Braves enjoyed one brief moment in the sun down south: the 1969 NLCS.

Forgive us if we don’t mind that he and his Western Division champion teammates didn’t make the World Series that year. Hank had to settle for a home run in each game of the Mets’ three-oh sweep. Given what Aaron did to Mets pitching as a matter of course — 45 regular-season home runs overall, including one that he launched into the distant center field bleachers of the Polo Grounds — it wasn’t surprising that he took Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry deep on consecutive days. Hank batted .357 in his final playoff appearance, including a Game Three double that spurred Ken Boswell to request a small favor when Aaron pulled into second base.

“Henry, we’re trying to win this thing. Let up on us, will you?”

[9]

[9]Apologies to David Aardsma, but there’s only one player who should lead off the Baseball Encyclopedia.

Methodically, he moved up myriad rankings to a point where attention had to be paid to the low-key right fielder from Alabama. No fewer than 120 games played each of his first 20 years. More hits and runs upon retirement than anybody other than Ty Cobb. More runs batted in than anybody to this day. And that home run record, the one Hank wristed his way to via consistency even the most finely tuned machinery would envy. From his second season through the eighteen that followed, Hank never produced more than 47 homers, but he never delivered fewer than 24. He passed 500 when hardly anybody belted 500. As he approached 600, he trailed only Babe Ruth and Willie Mays. Mays ran out of steam and, with Willie in a Mets uniform, Aaron passed him. Without flash, Hammerin’ Hank was on his way to matching the legendary Bambino.

Why this didn’t sit well with every living, breathing American mystified me as a kid. I thought it was the greatest thing to ever happen to baseball, 1969 Mets included. Nobody was ever gonna pass Babe Ruth’s 714, except now somebody was. Who wouldn’t root to witness uplifting history of this sort?

The worst elements of our society, apparently, the ones who wrote him threatening letters because Hank committed the imagined crime of slugging while Black. I wasn’t naïve; I knew there was such a thing as racial prejudice when I was eleven years old. I knew that if Hank had been born a little sooner he wouldn’t have had the opportunity to have taken his talents from the Indianapolis Clowns to the Boston Braves organization. I knew the promotion of Jackie Robinson, who was fifteen years older than Aaron but debuted in Brooklyn only seven years before Hank was called up to Milwaukee, hadn’t solved everything. Yet I wouldn’t have dreamed mindless, hateful prejudice would extend to beloved baseball idol Henry Aaron on the precipice of heretofore unimaginable achievement. This was 1974, not 1947. I wouldn’t have dreamed a lot of awful dreams when I was young.

Hank Aaron finished 1973 with 713 home runs, one shy of Ruth. There was no way he was gonna not hit his 714th and 715th as soon as the next season started. Topps knew it and threw him a coronation ahead of time. Card No. 1 dispensed with the standard niceties and dubbed him the NEW ALL-TIME HOME RUN KING right on the front. The five cards that followed encompassed reproductions of every Aaron issue covering his preceding 20 seasons in the big leagues. Topps didn’t do anything like this for anybody else. You didn’t need a Baseball Encyclopedia to understand Hank Aaron’s pending accomplishment was bigger than the game itself.

Ruth was tied on Opening Day. Four nights later, he was passed. Babe Ruth was still Babe Ruth. But Henry Aaron was now every bit as transcendent. He was an American idol. I don’t know that all of America deserved him, but the vast majority of us applauded fervently. What a privilege to be a kid watching Hank Aaron ascend as he did. He added forty home runs over the rest of his career — the final two seasons of it back in Milwaukee as a Brewer — and left us the legacy of 755. It’s not the most home runs anybody ever hit in the major leagues. But it is, like Hank Aaron, the grandest of baseball figures.