It’s a summer night in 2008. Utilityman Marlon Anderson has gone on the 15-day DL with a strained hamstring. To replace him, the Mets, in Houston, look to their geographically proximate Triple-A farm club in New Orleans and call up from the Zephyrs infielder/outfielder/hitter Daniel Murphy [1]. His first plate appearance, versus Roy Oswalt, results in a single. Twenty at-bats into his major league career, he’s a .500 hitter [2]. At the end of his abbreviated rookie season, his average is .313. He has played in 26 games at Shea Stadium, all of them with the pressure of a playoff race falling on his inexperienced shoulders. After 2008, Daniel won’t ever play at Shea again and will wait a long time to chase anything resembling a pennant.

The infielder/outfielder/hitter drops one of his identifying descriptors pretty quickly, as quickly as he drops a fly ball in left [3]. The glove of Daniel Murphy — “Murph” to us, even if you’d think such common shortening was permanently proprietary to legendary announcer Bob Murphy — is confined to the infield as 2009 gets rolling. He’s not really a natural there, either. What Murph does is hit. Not .500; not .313; not enough to forgive his shaky fielding and iffy instincts when he’s a sophomore, but he settles in. Citi Field is new. Few can swat homers over its comically far and tall walls. Murph leads the Mets in dingers with a dozen.

If he’s not gonna be our third baseman (we have David) and he’s not gonna be our first baseman (we’ll have Ike), Murph has to be something. He played a little second at Binghamton. He’ll play a little more at Buffalo in 2010. Get the hang of the position and come back to the bigs. Except he gets wiped out by an opposing baserunner and what was going to be his third year is wiped out with him. But an idea has been hatched and, come 2011 (after the incredibly ill-advised Brad Emaus experiment implodes on contact), Murph is indeed the Mets second baseman of the present. Sometimes. He plays everywhere on the infield as needed. David Wright misses time. Ike Davis misses more time. Murphy’s a third baseman some days and a first baseman others. One Sunday when he’s a second baseman, he takes a spike to the knee and finds another season prematurely ended. Double plays have become double jeopardy. Before 2011’s over, however, Murph’s hitting .320 on August 7.

Once recovered, the Golden Age of Murph is at hand. For three seasons, Daniel plays almost every day, usually at second. Tim Teufel works him into a state of defensive adequacy. Murphy plays on the edge of the grass, where it’s safest, as with training wheels. When nobody’s looking, he steals bases, successful on 46 of 56 attempts from 2012 to 2014. Sometimes he gets himself thrown out running any which way but wise. But he keeps hitting, to a composite tune of .288. In 2013, he’s the only Met position player to not miss time and finishes second in the National League in hits. In 2014, he alone represents the Mets at the All-Star Game. Is Daniel Murphy a star? Not really, but there isn’t much glitter to these perennially languishing Mets. They win 74, 74 and 79 games. Somebody has to hold our interest when the more fascinating among the Met pitchers are idle. It’s the ability to keep us going that makes this Murph’s Golden Age.

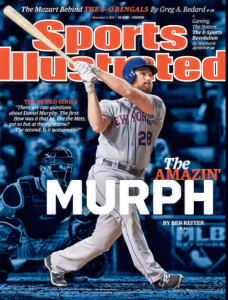

Then comes 2015, with its autumn nights in particular. The Mets are still playing, having captured the division title they missed when Murph was a rookie and Shea was condemned to the wreckers. He’s had a good year. He’s about to have an epic postseason. He and the pitchers defeat the Dodgers [5]. He and his sweet lefty power stroke combine to crush the Cubs [6]. Don’t let Murph hear you say that, though. In every postgame interview session — where Murphy’s presence is dictated by his in-game performance — he namechecks 24 teammates before he mentions any of his seven homers, including the six he bashed in consecutive NLDS and NLCS games. He’s humble. He’s real. He was real in Spring Training, too, when he kind of put his foot in his mouth (something about “lifestyle [7]”), but you couldn’t say he wasn’t being his version of real then as well.

It’s also the real Murph who appears in the World Series, the one who was never extraordinarily comfortable at any position other than hitter. Since 2008 he’s made some crazy good plays wherever he’s been asked to station himself, but the routine ones have had a tendency to bedevil him. One in particular, a grounder in Game Four, contributes directly to a win becoming a loss. Just about everybody on the Mets contributes across five games to a potential world championship transforming into a “nice try, fellas.” Murph the NLCS MVP doesn’t register as remotely valuable versus Kansas City. Except for the crowds, it might as well be some night at Citi Field in the depths of 2013. Like Ray Knight and Mike Hampton, Daniel doesn’t play a single regular-season Mets game after winning individual postseason honors. Earning a trophy for yourself in October seems to be the quickest ticket out of Flushing.

As a Washington National in 2016 and 2017, Murph becomes Ryne Sandberg against everybody and Stan Musial against the Mets [8]. It might not have been the worst idea to let him walk. It becomes the worst actuality [9], but back on that night in 2008 when the Mets simply need to replace Marlon Anderson, who would guess the 23-year-old minor league callup without an obvious position is going to help define an entire era of Mets baseball? He is going to embody the blah years and personify a joyous if transitory vault into the stratosphere. He is going to be Murph of the Mets, and when he announces, at the age of 35, that he’s retiring ahead of the 2021 season, we’ll put aside his stints with the Nationals, the Cubs and the Rockies and recall him primarily as Murph of the Mets. He was ours. He still is.

Daniel Murphy goes down as the last active position player who played for the Mets at Shea Stadium [10]; two relievers endure as major leaguers as the next Spring Training approaches. Joe Smith, who dates to 2007, is still an Astro. Ollie Perez, veteran of 2006, is still a free agent, but maintains the ability to throw with his left arm, so he’s probably good to go for the year ahead. Shea’s long gone. The first generation of Citi Field Mets have commenced their collective fade into memory. The Longest Ago Met Still Active [11] who didn’t play at Shea is Justin Turner. LAMSAs keep coming from later.

Murph keeps speaking well of his Met teammates. In discussing his decision to stop playing [12] — having become a player of enough stature to “retire” rather than just not get an offer — he remembers the company of others rather than his own accomplishments. To SNY’s Andy Martino, he says of deGrom and Duda, Familia and Lagares, Tejada and Flores, “We all grew up together. We did life together,” a quintessentially Murph framing of rising and eventually succeeding as a Metropolitan. Those are your 2015 National League champions. They, too, grow temporally distant. That happens in baseball.

So does, if you’re lucky, the occasional Murph, someone whom a stubbornly engaged fan might notice [13], amid the persistent mediocrity his team churns out, making himself over “from sub to grinder to hero…continu[ing] to sandwich base hits”. You could do worse than to order the Daniel Murphy, side of fundamentals angst notwithstanding. As a hitter, he was one of the best at his position. As a Met, he is one of the characters you don’t forget.

I joined Mike Silva’s Talkin’ Mets podcast to delve a little more into Murph. You can listen here [15] (I come on around the 26:00 mark).