The Mets lost their first exhibition game on Monday afternoon, but they won a ton of goodwill Monday morning by unveiling the patch they will wear on their uniforms throughout 2021 in memory of Tom Seaver. The homage presents the retired-number disc that hangs in the left field rafters at Citi Field in miniature: 41 in orange and blue, set against Met pinstripes. It’s literally a small thing, but it’s tastefully and heartfully done. Last September, in the wake of the sad news of Seaver’s passing, the Mets went with a white number on a black patch, matching the mood of a month and a year no Mets fan minded coming to a quick end.

This iteration of 41 looks Terrific, which couldn’t be any more Franchise-appropriate.

We will wear a “41” Tom Seaver tribute patch on the right sleeve of our home and road uniforms during the 2021 season. https://t.co/f4Q7vhdg33

— New York Mets (@Mets) March 1, 2021

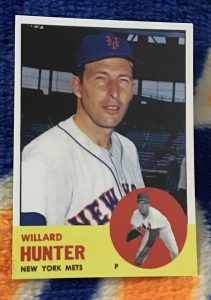

Another Met pitcher, who threw for Casey Stengel in 1962 and 1964, passed away recently. He won’t get a patch. From what I can tell, Willard Hunter wouldn’t have expected let alone particularly wanted one. Nor would have the longtime Nebraskan, who died February 3, cared had he known he was the trickiest third-of-an-answer to a straightforward Mets trivia question. There was nothing inherently tricky about his presence in the answer, actually. He was just the one I was slowest to get.

The question was posed to me by Mark Simon, who you might know as a maestro of metrics for Sports Info Solutions and, before that, one of the aces dealing data for ESPN Stats & Info. Secretly in the mid-2000s he blogged about games the Mets won via walkoff hits and such, along with other Mets minutiae. The blog wasn’t secret, but his identity as its author was supposed to be. If you knew the blog and you knew Mark, there was no way you couldn’t have gotten whose blog it was in one guess.

On a Friday night in Flushing long ago, Mark and I sat down for a game together. His way of saying hello was to ask me to name the three Met pitchers who’d won both ends of a doubleheader. The third pitcher to turn the double-trick was easy: Jesse Orosco, July 31, 1983. Maybe it wasn’t easy per se, but it was easy for me. July 31, 1983 was an intensely memorable Mets doubleheader sweep for Mets fans of that era. It’s the one that ended with Mookie Wilson scoring from second base on a groundout in the twelfth inning. The first game also went twelve. And it was Banner Day. Both games being won by the same pitcher — our only All-Star that season — made it too perfect to forget.

The first was Craig Anderson, in 1962. That one-two stayed with me from some previous recitation of the question in question. Craig Anderson lost his next nineteen decisions after winning the two games of May 12 — each on a Mets walkoff, Mark would want you to know — establishing a wrong-way record that would stand until Anthony Young came along in 1993. You tend to remember when somebody who mostly lost won twice in a day.

The second pitcher who made up that tricky third of the answer? I had to think about that. Then I had to accept a couple of hints. Mark took pity on me and told me the pitcher’s first name began with a “W,” which seems appropriate for a fella who collected a pair of them at once. Eventually I whittled it down to Willard. Not Willard Hershberger, I thought out loud (Reds catcher Willard Hershberger was the poor soul who took his own life in the midst of the 1940 season)…oh, I know: Willard Hunter!

That might have been the last time any Mets fan added an exclamation point to lefty reliever Willard Hunter, whose 5.06 ERA in 68 games as a Met may have unleashed less effusive punctuation in real time. Though I didn’t know the man, I somehow don’t think he would have minded not being the cause of Mets fan excitement after a while. I make this presumption about Mr. Hunter’s post-career state of mind based mostly on this “where are they now?” note published in Janet Paskin’s entertaining 2004 book Tales From the 1962 New York Mets Dugout:

After baseball, Hunter went on to work in computers. Now retired and living in Nebraska, he doesn’t talk about the Mets. He put his brief stint as a major league baseball player behind him.

“He was famous at one time,” his wife said, “And now he doesn’t want to be noticed by anybody.”

That’s a valid choice. Hunter’s final major league appearance came in 1964. Four decades later, a reporter tried to track him down to ask what it was like to be part of the worst team in baseball history. The man demurred. Still, after prowling about for a little more information to complement the one piece of trivia I had on him, I infer that he must have been courteous to the fans who knew of him from baseball. I saw his autograph pop up here and there, at least once signed with “best wishes”. Agreeing to sign to fill out somebody’s collection means a lot to completists. Adding a pleasant greeting is just good manners.

Then again, maybe not saying much was always part of his lifestyle. Willard’s 1964 teammate Bill Wakefield told Bill Ryczek, author of The Amazin’ Mets: 1962-1969, about a game Hunter organized to pass the time in the bullpen. “We tried to see how long we could go without talking,” Wakefield said in Ryczek’s essential 2008 book. “We all put a couple of dollars in the pot and whoever talked was out.” This proto-version of Seinfeld’s “The Contest” could lead to a little confusion, like the time a Met right fielder came running to make a catch of a foul pop nearing the stands in Crosley Field and the relievers remained mum rather than shout “LOOK OUT!” or give any kind of direction, which is what the guys in a bullpen situated in foul territory were supposed to do.

“He looked at us and said, ‘What the hell’s wrong with you guys? Can’t you talk?’” Wakefield remembered. “We just looked at him.”

You had to look at Hunter with admiration at the end of a long Sunday afternoon at Shea on August 23, 1964. As it was on Orosco’s pleasure-doubler in 1983, it was Banner Day, the second in Mets history. Naturally, with a big parade divided the twinbill. The opener versus the Cubs had been a pitchers’ duel, with Galen Cisco scattering four hits over eight innings and giving up just one run. Chicago starter Bob Buhl would go beyond regulation, as the affair required an extra inning. The lidlifting festivities weren’t decided until Ed Kranepool singled with the bases loaded off Lee Gregory. Buhl took the loss despite going nine-and-a-third.

The winning pitcher in the 2-1 final, after a clean two-thirds in the top of the tenth, was Willard Hunter. The winning banner among the 1,031 streaming through the center field gate read “EXTREMISM IN DEFENSE OF THE METS IS NO VICE,” a play on the Barry Goldwater message that lost the Arizona senator 44 states and the District of Columbia.

The Mets, on the other hand, were about to win their day in landslide, capturing the nightcap in the bottom of the ninth, 5-4, on another bases-loaded single, Charley Smith delivering the deciding RBI off Don Elston. And who should be the pitcher of record? Willard Hunter once more, having hurled a scoreless top of the ninth to keep the game knotted at four. You’d have to call the half-inning that followed Hunter’s heroics pretty stubborn, as the Mets seemed in no rush to win despite the Cubs’ determination to lose.

Bobby Klaus led off with a single. Ron Hunt bunted him to second. Klaus took third on a wild pitch. Joey Amalfitano, nominally managing the Cubs as part of its infamous college of coaches, directed Elston to intentionally walk Joe Christopher. Then he ordered George Altman walked. No way the Mets couldn’t win now, except Jim Hickman popped up. Smith then lined a ball into left-center, ensuring Hunter’s name would live alongside Anderson’s and, eventually, Orosco’s.

Seeking a contemporary angle about Hunter’s dual feat of strength — what was being said in ’64 — taught me a couple of things:

1) Willard Hunter wasn’t necessarily referred to as Willard Hunter on his most productive professional day. Red Foley referred to him as “Hawk Hunter” in the Daily News. Frank Litsky in the Times called him “Bill Hunter,” as does the roster in a 1964 program I happen to have handy. Maybe he invented that game about not talking because he got tired of responding to so many first names.

2) None of the next-day coverage I could access, nor what awaited a couple of Saturdays later in the Sporting News, made a whole lot of hullabaloo over Hunter being the winning pitcher twice in one day. Just the fact that the 1964 Mets were hot, having won seven of eight, seemed to overwhelm the gentlemen of the press.

On one hand, barely noting the winning pitcher’s accomplishment is understandable, in that the winning pitcher totaled just an inning-and-two-thirds of work (while Cisco got bupkes for his eight almost spotless innings). These days we scoff if anybody makes too much of pitcher wins.

On the other hand, Willard “Bill” “Hawk” Hunter won two games in one day! Most of us don’t win anything on any day. Maybe if the media had known no Met would do it again for nineteen years and then nothing like it would happen for another thirteen years after that, when John Franco saved a first game and won a second game versus the Pirates on July 30, 1996, and then there’d be nothing even like that by a Mets pitcher from 1996 through the first season of the third decade of the 21st century, when doubleheaders were never scheduled in advance; Banner Day was a gauzy memory; and if two games were reluctantly played in one day, they were allotted no more than seven innings apiece (with extra innings bastardized by a runner starting each half-frame on second base)…maybe if the media had known all that, Willard Hunter would have garnered headlines rather than agate type.

C’mon, people of 1964, get excited — Willard Hunter won two games in one day!

Well, I’m excited in retrospect. Willard’s pair of W’s, which constituted half of his career total, leapt to mind a couple of nights ago when I learned the pitcher had passed away in early February at age 85. That unfortunate update to the all-time Mets mortality table is what caused me to try to learn a little more about a man who was apparently fine with you not knowing any more than his baseball record revealed. The obituary posted by the Omaha funeral home that handled his services mentioned his wife, his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but nothing about baseball. Perhaps Hunter viewed those as his biggest wins, even if they were accumulated in a span longer than a single afternoon.

Beautiful tribute. Reminds you that even the fringest of major leaguers accomplished something noteworthy in their lives. RIP.

Now, regarding the Orosco doubleheader – I think I’ve mentioned before that those were the first two major league games I ever attended in person. A few other noteworthy things:

– First, as gloriously as the day ended, that’s how horribly it began. Walt Terrell started the first game, and the only four batters he faced produced three walks followed by a grand slam. (Remember, these were the first four major league AB’s I ever saw.)

– In the second game, Jose deLeon no-hit the Mets for 8-1/3 innings and got a no-decision. For the Mets, Mike Torrez pitched 10 shutout innings (imagine that today!) with the same result. It was all Jesse and Mookie.

– Finally, the winning banner that year was almost as clever as the 1963 winner. It highlighted the sad fact that in 1983, opponents’ half-innings tended to last a long, long time. It read simply, STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER.

Very nice, thanks. I didn’t specifically remember That Sunday That Summer (Nat King Cole, 1963; Willard Hunter, 1964) but somehow when I saw Willard Hunter’s name here I did think of “Hawk” Hunter. I’m not sure if Red Foley ever made all that much of an impression on me, so I’m thinking Bob Murphy may have referred to him as “Hawk” from time to time. Such as on August 23, 1964. Most likely with the tone of admiration in his voice that he employed when a Met did something good,

69 MLB appearances, not too shabby at all. Thanks again.