Certain Mets seem to come up semi-regularly in this space. Not necessarily from being great and, I’d like to think, not from my being cute or ironic. Certain Mets just hover in my baseball subconscious and briefly but habitually waft above the rest.

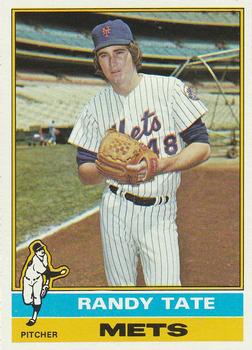

Randy Tate [1] was a certain Met. He pitched for the Mets in 1975. Not before. Not after. I hadn’t heard anything about him in the minor leagues ahead of his major league debut. He appeared at Shea that April, spent the summer, and didn’t pitch there again after that September. Or anywhere else in the bigs. It never occurred to me to strenuously wonder where he went. I figured the Mets had their reasons for elevating Randy Tate when they did and for going in a different direction when they did.

But in 1975, the season I was 12, which is a prime age for forming impressions and attachments, Randy Tate was the Mets’ fourth starter. The rotation was Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Tate and whoever else was handy. I was already attached to Seaver, Matlack and Koosman. I was impressed that Tate could hang with them.

Randy Tate may not have been in a class with the three pitchers he followed, but for a year he was in their league. Once in a while, he was what you meant when you talked about Met pitching depth. I went to Old Timers Day in late June. Casey Stengel came out in a Roman-style chariot and greeted us, his eternal subjects. Rookie Randy Tate pitched. I watched the Ol’ Perfesser — Casey was 84 — wave, and I watched the latest example of the Youth of America — Randy was 22 — take care of the Phillies for a couple of innings. Then the rains came down and my sister, who was kind enough to bring me in the first place, insisted on leaving, not quite buying my explanation that sometimes it stops raining, a grounds crew dries the field and the teams pick up where they left off. The game resumed while we were on the LIRR to Penn Station, where we’d take another train back to Long Beach. We came home to find Randy Tate on Kiner’s Korner. The rookie had just claimed his first complete game victory.

That was the last time Casey Stengel made an appearance at Shea Stadium. It was also the last time I saw Randy Tate pitch there.

Old Timers Day isn’t what most former 12-year-olds and thereabouts from 1975 Metsopotamia remember Randy Tate for. We go almost immediately to Monday night, August 4, when Randy was going to pitch the first no-hitter in New York Mets history. No kidding, this was gonna be it. Fourteen seasons of Mets baseball and it was already an albatross that we had no no-no. That stupid bird was gonna fly away that night. I could feel it. Bob Murphy could feel it. I listened while in the bathtub. That afternoon my mother took me to the dermatologist in search of relief for the nagging psoriasis on my right knee. The doctor gave me a bottle of tar. Or something with tar in it. Add it to your bath, he said. It had a very strong aroma. I swear I can still smell it, just as I can still hear Murph narrating Tate’s total and complete domination of the Montreal Expos.

The no-hit bid lasted into the top of the eighth. Leadoff hitter Jose Morales struck out, Randy’s dozenth K. We were up, three-nothing. Could this be the night? This had to be the night. I wasn’t a naïve 12-year-old Mets fan, mind you. I’d been at Mets fandom since I was six. No Ned in the third reader as Casey would have said. I wanted to believe Randy Tate would get it done, that our lives wouldn’t be defined by not having a no-hitter for another who knew how many years. This wasn’t Seaver or Matlack or Koosman. This was Randy Tate. This was so crazy it might work.

Except Jim Lyttle, the ex-Yankee, singled to break up the no-hitter, five outs from glory. Murph said the fans at Shea were giving Tate a standing ovation. I hung tight in the tub. The next four batters were all future Mets and three of them destroyed the remnants of the dream I dared to dream for the current Mets. Pepe Mangual walked. Jim Dwyer struck out — Randy’s thirteenth — but Gary Carter singled in Lyttle to end the shutout, and Mike Jorgensen, a former Met as well as a future Met, launched a three-run homer that in retrospect was inevitable. I could hear the heartbreak in Murph’s voice. I could feel the heartbreak while soaking in that slimy black water. Yogi Berra let the kid finish the eighth. Today a rookie who was en route to striking out thirteen over eight wouldn’t see the sixth inning

Tate took the 4-3 loss. I never used the tar concoction again. It was really pretty disgusting.

The next day, Berra managed his last two games for the Mets, a doubleheader sweep, each a seven-zip whitewashing from the Expos. Yogi was fired the day after. Within two months, Casey and Mrs. Payson were gone. And though he couldn’t have known it for sure, Randy Tate was finished as a Met, his career line frozen at 5-13, a 4.45 ERA and 99 batters struck out in 26 games, 23 of them starts. He didn’t immediately leave the organization, instead spending two more years in our minors, pitching for Tidewater in ’76 and Lynchburg in ’77. There’d be an additional season of pro ball in the Pittsburgh chain. After that, you have to visit Tate’s Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page [3], which is thick with talk of the near no-hitter and the turns his life took in Alabama after baseball.

When I learned tonight through Facebook [4] that Randy Tate, 68, had died from COVID complications, it was again raining on Old Timers Day; it was again tar-drenched in the bathtub; it was again 1975 when a righthander who wasn’t Jacob deGrom wore No. 48 for the Mets and a 12-year-old was thrilled to root for him, even if the 12-year-old knew he’d be forever dismayed that Jim Lyttle broke up what should’ve been the first no-hitter in New York Mets history. Or the second after Seaver got Qualls six years earlier.

With certain Mets, that feeling never goes away.