From the deep well of numerical sustenance baseball is wont to give us on any given day, Thursday afternoon it gave us, among other digital delights, 7 1-hit innings from Taijuan Walker; 1 base hit from Francisco Lindor after 26 hitless at-bats; 11 walks issued to would-be Met batters from Cardinal pitchers (including 4 consecutive in the top of the 5th); a franchise record 17 Met left-on-baserunners who prized their status so dearly that they refused to exchange it for a run; and, in a teeth-pulling nod to the American Dental Association, a 4-1 getaway day Met win [1] in St. Louis.

We accept this result as Lindor accepted his trio of walks: all smiles. Francisco posted a .667 on-base percentage for the game and the Mets re-reached .500 for the 8th time this year.

Quite an eventful May 6, though to be honest, May 6 didn’t need any help from the Mets or the Cardinals to feel eventful — though someone who used to play for the Mets and someone who used to play for the Cardinals would take over most of the day’s baseball headspace. What needed to be done to make May 6 special happened when former Met and eternal immortal Willie Mays turned 90. Willie Mays has made every day he’s been associated with the playing of baseball special since he first picked up the game and then lifted it higher than anyone before or after him.

https://twitter.com/mlbnetwork/status/1390317724191055874

Tom Verducci wrote a tribute for MLB Network [2], narrated by Danny Glover, that dipped into the aforementioned well of numerical sustenance, but with a caveat: “You would no more define Mays by his 3,283 base hits than you would Miles Davis by albums sold.” The numbers were the steak. The player was the sizzle. The combination, as a plethora of birthday wishes underscored, is what made Willie a dish unsurpassed in baseball annals. Mike Lupica’s column [3] for mlb.com said it as well as anybody:

Willie Mays is the greatest all-around player who ever lived, whose legendary career started at the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants in 1951. It means that for so many lifelong fans, he is the greatest player they never really saw. Even for the ones who did see him at his best, in the 1950s and ’60s, in New York and San Francisco, they go mostly on memories now, ones that No. 24 burned into their imagination forever.

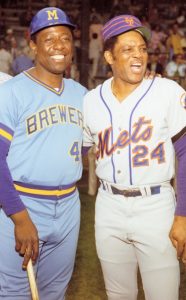

Still, annals are numerically inscribed, so whenever somebody has passed Willie Mays in some statistical category, it gets your attention. His stats aren’t very reachable to begin with, so it takes a special player to outpoint them. Take home runs. Hank Aaron slugged by Willie Mays late in both their careers. It was only slightly jarring. Aaron was Aaron, even though Willie was Willie and I’d never known a time where Willie wasn’t running 2nd to Babe Ruth on baseball’s most glamorous chart and/or table. In 1972, Willie the Met gracefully settled into 3rd place. Ruth, Mays, Aaron became Ruth, Aaron, Mays, which in short order became Aaron, Ruth, Mays — 755, 714, 660, respectively. That’s a Top 3 you can commit to memory and take to heart for the rest of your life.

If you lived to 2004, however, you saw the order upended. Barry Bonds passed Willie Mays with his 661st home run that April. Once Barry tapped previously unknown sources of power, his ascent up the list was inevitable. Nobody seemed prouder of the new No. 3 than the new No. 4, Bonds’s godfather Willie Mays. If it had Willie’s blessing, well, fine. Top 4 is still a pretty spectacular club, membership consisting of 4 giants and 2 Giants,

Bonds would go on to skip past Ruth and Aaron. A nation mostly held its applause. The Top 4 remained the Top 4 in composition if not order until 2015, when Alex Rodriguez hit No. 661. That truly annoyed me — A-Rod… — but what are ya gonna do? However he came to hit them, the man hit them. The totals were the totals. The Top 4 suddenly didn’t include Willie Mays. But the Top 5 did. As anyone who has repeatedly watched High Fidelity grasps, Top 5 has cachet. I wished Willie hadn’t been surpassed in home runs, but, honestly, can anybody be said to have surpassed Willie Mays?

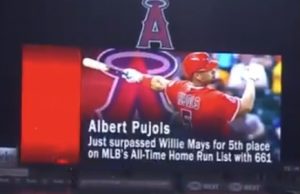

The thought process came up again on September 18, 2020, when Albert Pujols of the Los Angeles Angels emerged from what seemed like a decade of Orange County hibernation to swat his 661st career home run. In a vacuum, I was all for Albert. He may be the last baseball player of a non-Met nature I would’ve been instinctively tempted to tack to my bedroom wall in poster form if I hadn’t been nearing 40 years old when Pujols emerged fully formed as the grandest Cardinal hitter since Stan Musial. For me, personally speaking, he’s always resided in that hushed “wow” strata of superstars, and that’s a difficult circle to open for entry when you’re not a kid anymore. I recognize greats to this day, but I haven’t been able to conjure awe for any who’ve debuted past 2010, and even then (Votto, Posey, Freeman) it’s more like solid appreciation. I’m reasonably familiar with the astounding work of Mike Trout and the Bettses, Sotos and so forth who’ve followed in his tracks, but I think there’s too much distance for me in my late 50s to get overly excited about anybody who’s not a Met. I’ve been watching baseball for more than a half-century. When it comes to baseball reverence, I’m not actively accepting new applications.

Albert Pujols and Miguel Cabrera have been the last players in other uniforms I’ve put on a pedestal. Pujols came up in 2001, Cabrera in 2003. I was too old to look at ballplayers that way by the time they swiftly ascended to their prime, but habit was habit. I looked at Bonds that way. Didn’t love him, can’t say I revered him, but part of me never lost the awe. Mike Schmidt struck me similarly, and believe me, I more or less hated Mike Schmidt. Vladimir Guerrero. Jeff Bagwell. Dale Murphy. Joe Morgan. Johnny Bench. Lou Brock. A couple of handfuls of others, maybe, all the way back to Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron and, of course, Willie Mays.

I was partially glad Pujols was still capable of knocking balls out of parks when he drew attention for hitting No. 661 last season — and then hit No. 662 in the same game. But I partially mourned Albert’s accomplishment because now Willie Mays’s 660 wasn’t even in Top 5 territory. Not that Top 6 isn’t sensational in the grand sweep of history, but it’s not Top 5. Willie Mays was more than home runs, more than statistics, more than what can be drawn from the numerical well. Even still. I don’t know where Miles Davis’s record sales rate versus, say, Kenny G’s, and I understand Billboard doesn’t measure artistry any more than Baseball-Reference does…but Willie Mays not in the Top 5 of all-time home run hitters? What is baseball without the statistical certainty on which we rely?

We’ll find out soon enough.

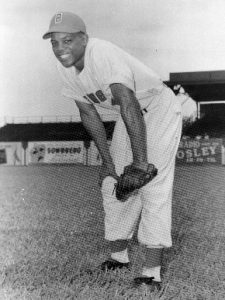

In the offseason, Major League Baseball announced [6] it was ready to encompass under its statistical umbrella what we casually refer to as the Negro Leagues. Specifically, we’re talking the first version of the Negro National League (1920-1931); the Eastern Colored League (1923-1928); the American Negro League (1929); the East-West League (1932); the Negro Southern League (1932); the second version of the Negro National League (1933-1948); and the Negro American League (1937-1948). We might as well get to know the specifics. Until this move, too many of us have treated Black baseball as a gray area. We’ve heard of it. We admire what we know about its contents. We rue that society couldn’t bring itself to bring players of all colors onto the same field. Then, probably, we refer to thinking about “the major leagues,” which we reflexively know as the National League and American League, pre-Jackie Robinson and post-Jackie Robinson.

Well, suddenly some 3,400 players who never had the chance to be what have been called big leaguers will be called big leaguers. Separate leagues, equal footing, if you will. I was fortunate enough to sit in on a Zoom call with Negro League Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick the December night the decision was announced. He called what was going on a matter of having “started the process of rewriting American history”. Good, I thought. American history could use all the help it can get. Same for baseball history.

Righting historical wrongs is Job 1 here. This is a tiny step in that direction. Blending numerical ingredients to create a satisfying statistical stew is next. If hits collected in games that weren’t sanctioned in their institutionally racist times are indeed major league, that unsettles the lists we’ve known all our lives. But if records are made to be broken, recordkeeping is made to be repaired. Figuring out where Oscar Charleston and Josh Gibson fit on a spreadsheet that already included Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb rather than confining their exploits to hazy legend will be a challenge. It will be worth it. It would have been better had everybody gotten to play in the same leagues. That ship refused to sail even a little until 1947. Statistics will have to do.

Among the gems unearthed by the monumental rediscovery process of these leagues was a newspaper report that noted a 17-year-old playing for the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro American League homered against the Cleveland Buckeyes on August 11, 1948. A box score would be nice to have, but thus far none has been found. Still, the Birmingham News covered the event. And it was an event: It was the 1st home run of Willie Mays’s major league career.

Yes, major league. That’s what the Black Barons were in practice and now that’s what the Black Barons will be in the annals. Thus, when Willie Mays was called up from the minor league Minneapolis Millers to play for the major league New York Giants on May 25, 1951, he had 1 major league home run in his pocket. For the Giants and Mets between 1951 and 1973, he’d hit 660 more, allowing him to end his major league career with 661.

That’s different. Slightly different, but different. Or not that different because, again, he’s Willie Mays, for whom the back of a baseball card constituted merely supporting evidence for what everybody watched him do on professional baseball fields from 1948 forward. Sort of like Albert Pujols’s 667 home runs are a mammoth total, but it’s the explosiveness of Albert’s swing that will stay with me long after the cruel irony of the Angels designating 41-year-old Pujols for assignment on May 6, 2021 — Willie Mays’s 90th birthday — is relegated to a footnote.

Nevertheless, despite a quarter-century’s worth of witnesses having attested to the greatness of Mays without feeling compelled to cite statistics, it somehow seems discordant to me that when we rattle off the Top 5 home run hitters in major league history, the list won’t include Willie Mays. Until last September, I’d never lived consciously as a baseball fan when Mays wasn’t up there. He was 2nd to Ruth; 3rd to Ruth and Aaron; 3rd to Aaron and Ruth; then Bonds and Rodriguez got involved. Finally, Pujols nudged him to 6th.

When, I wondered, did Willie reach the Top 5? I would have guessed he was born with 500 home runs, but no, he had to hit them like everybody else. By the time he got to No. 500 (or the 500 he hit in the NL after he moved on from the Black Barons) on September 13, 1965, he was already in the Top 5. The order was Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, Mel Ott, Willie Mays. It had been listed that way for just over two weeks.

It got listed that way because of a home run Willie Mays of the San Francisco Giants hit at Shea Stadium against the New York Mets. The ball Willie socked was recognized as No. 494, or 1 more than Lou Gehrig, the former No. 5 all-time slugger, had hit. What made it delicious then and keeps it delicious now was the extra significance it carried. The date, you see, was August 29. The month was almost over. What a month August 1965 had been for Willie Mays…which is what could have said for Ralph Kiner in September 1949. In September 1949, Ralph hit 16 home runs. It was a National League record for most home runs in a month that had stood nearly 16 years.

But records were indeed meant to be broken, whether the reigning recordholder wished it shattered or not. Most recordholders, however, don’t have to describe to who knows how many people the shattering. Ralph Kiner had to. It was his job. He was calling the Mets-Giants game of August 29, 1965, just as he called every Mets game for a couple of generations. Ralph was working the radio side in the top of the 3rd inning that Sunday afternoon as the only other National Leaguer to have hit 16 home runs in a month stepped to the plate.

How did Ralph handle situation? Let’s listen in [8].

Willie Mays the batter.

And his 1st pitch is inside, a fastball, Willie started to swing and then spun around but held the bat back, and it’s ball one.

Mays all geared up, he’s got 40 home runs and 86 runs batted in. He’s batting .325. He has been on a terror streak here in this month, having hit 16 home runs so far.

Willie 5-for-9 against the Mets in the series.

And Fisher now back, in a 1-0 hole, and the next pitch is in the dirt for ball 2, and Mays says, ‘look at the ball,’ so the home plate umpire Stan Landes takes a look and throws it out of play.

2 balls, no strikes on Willie Mays.

Fisher a look at 1st and a throw there, but Gabrielson who picked off at 1st base his 1st time on only a couple of steps away. He was only a few steps away when he was picked off.

Now the 2-0 pitch. It’s hit deep to left field, going, going, going and gone!

So Willie Mays writes a new record book in the National League. He has just hit his 17 home run in the month of August, and that is an all-time record in the National League.

Well, it had to happen, there is no doubt about that.

Willie is hot, he’s the hottest man in baseball. He’s certainly a Hall of Famer, 1 of the greatest players that ever lived. That home run, his 494th, puts him ahead of Lou Gehrig in the home run derby, and it also knocked out Jack Fisher.

A high changeup, a perfect pitch for Mays to hit, it’s all over the left-center field fence.

And the Giants lead by a score of 5 to nothing on a 3-run home run. For Willie Mays, his 41st home run this year. He leads the major leagues.

Coming in now lefthander Gordon Richardson in place of Jack Fisher…

“In three games, I’ve seen two of my records broken by Willie,” Ralph said. “Sure, it hurts a little. A guy likes to have his name in the big book. but if somebody had to break them, I’m glad Willie did. He’s amazing.”

Ralph was all class. So was Willie. So, for that matter, was Lou. Lou Gehrig took a back seat to Willie Mays on the home run list, but he was still Lou Gehrig for posterity. Ralph Kiner took a back seat to Willie Mays on another home run list, but he was still Ralph Kiner, especially to us. Ralph was “certainly a Hall of Famer,” though the certainty wouldn’t be certified until 1975. Willie joined him in 1979. But it didn’t take them that long to get together after the record-shattering. Ralph had Willie on as his guest on Kiner’s Korner. It could have been uncomfortable had not so much class fit inside such a snug studio.

“Are you sore?” Willie asked his host.

“Sure, I’m sore,” Ralph responded as a great might to another great.

“I’m sorry, Ralph.”

Live 90 years, and you’re bound make somebody sore, even if somebody’s sort of kidding that he’s sore. Live 90 years like Willie Mays, and you’ll make most everybody happy.