They weren’t kidding when they said Jerry Koosman was clutch. Beat the mighty Orioles twice to tie and win the World Series? Yeah, that was swell, but look at what he’s accomplished lately.

• Jerry Koosman [1] shows up at Citi Field to have his number retired, and the 2021 Mets shake out of their characteristic doldrums and actually best another baseball team! Wonder of wonders! Miracle of miracles!

• As if inspiring the snapping of a four-game losing streak wasn’t enough, Jerry became the first Met player to star at a number retirement ceremony that preceded a Met win. Tom Seaver couldn’t do it in 1988 (Braves 4 Mets 2). Mike Piazza couldn’t do it in 2016 (Rockies 7 Mets 2). But the legend of Kooz is stronger than the curse of the rafters-raise.

The Mets indeed won one for Kooz. Or didn’t lose in proximity to Kooz. Either way, Mets 5 Nationals 3 [2]. You didn’t have to be the unofficial institutional memory of this franchise to notice the 5-3 score matched the final that certified the 1969 World Series as new York’s (WP — Koosman 2-0). Wanna cast Marcus Stroman plus three relievers as the practical equivalent of one complete-gaming Kooz? Go for it. Who was Kevin Pillar channeling with his two homers? Al Weis, who came out of nowhere to suddenly flex muscles against the Cubs and O’s? Ron Swoboda, whose pair of home runs confounded Steve Carlton on his 19-K night? Either works 52 years later.

Michael Conforto coming off the bench for the first pinch-hit home run of his career, the three-run blast that pushed the Mets ahead in the seventh — there’s a touch of Duffy Dyer on Opening Day versus the expansion Expos/future Nationals in that swing, even if Dyer’s detonation came in a losing cause. The 1969 Mets were a winning cause. They won a lot more than they lost ’cause of starting pitching that silenced the opposition and stunned the universe. They had Seaver. And Gentry. And McAndrew. And Cardwell. And Ryan.

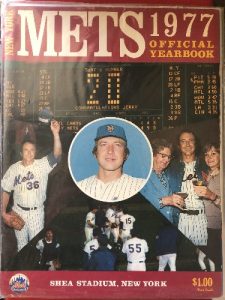

Plus that lefty who wore 36 in that most magical Met season and a plethora of Met seasons that spanned the emotional spectrum from delightful to depressing. Koosman himself was always delightful, whether on the mound or in the clubhouse or visiting Kiner’s Korner. When the Mets won in 1969 and 1973, you could attribute critical junctures of triumph to Kooz. When the Mets went so far south that the only postcards they could mail featured penguins, it wasn’t Koosman’s doing. I watched him lose 20 games in 1977 and 15 games in 1978. I saw a lot of hard luck. I never saw a losing pitcher.

Peculiar that an organization whose sporadic dalliances with excellence revolve around starting pitching didn’t get around to retiring the number of its best lefthander for an eternity. Divining the psychology behind retiring numbers saps the exuberance out of celebrating the players who seriously merit the honor. I don’t know why 140 wins and no less than a co-lead role in two storied postseasons required decades of mulling over. I don’t know why, when every retelling of Those Days always comes back to Seaver and Koosman, Jerry Koosman’s turn at digital immortality was skipped over like he was Jerad Eickhoff after a rainout.

I get that there was only one Tom Seaver. Perhaps it’s taken a long time to fully understand there was only one Jerry Koosman.

It’s a shame the two singular sensations couldn’t have shared this night. Koosman was on hand in 1988 for Seaver’s number celebration. Somewhere between 41 in ’88 and 31 in ’16, before Seaver’s health deteriorated, the Mets might have glanced at Koosman’s stats, heeded Koosman’s contemporaries and committed to the elevation of 36. It’s never too late to do right by history. But it can get too late to build the ideal guest list.

Those of us who made it to Citi Field on the late August Saturday night in 2021 when 36 was retired were treated to a warm evening — though not too warm on the thermometer, which fit Jerry Koosman’s pitching specifications to a tee. I’ve rarely heard Kooz interviewed when he didn’t volunteer he threw better when the air turned cool. Temperatures may have (blessedly) dipped, yet the Flushing atmosphere was warm and sweet and loving. You can’t do better for the end of summer or the last word on a professional journey.

The Mets don’t win as many games as we’d like, but they inevitably prevail at pregame festivities. The Hall of Fame gala four weeks earlier was a group hug for Matlack, Darling and Alfonzo. This coronation emitted a similar comfy-cozy vibe. Howie Rose is the emcee of our lives. Art Shamsky, Ed Kranepool and Wayne Garrett linked arms and hearts. Doug Flynn checked in with a video greeting. And Mike Piazza proudly stood (and spiritually crouched) as Jerry Koosman’s batterymate, 31 adjacent to 36 in the rafters. “Jerry,” said the only other man alive who knows what it’s like to stand before an audience of Mets fans while his number his unveiled in highest left field, “welcome home. This is your home, and this is your family.”

Koosman has always been family. Koosman’s family has always been family. When Howie introduced Jerry’s kids, I realized we’d met them in yearbooks and highlight films from Player Family Days gone by. One of the first things I think of when I think of Jerry was the absolute pride and joy our announcers expressed when he became a 20-game winner for the first time, in 1976. Couldn’t happen to a nicer guy, or words to that effect, Bob Murphy, Lindsey Nelson and Ralph Kiner iterated and reiterated that September. They weren’t talking about some pleasant fellow they knew a little from work. They were talking about our brother who looked out for our best interests; our cousin who always brought over something to make it a fun afternoon; our uncle who could teach us a few things. Whatever the relationship, we could relate to Kooz. He wasn’t just ours. He was, intrinsically, one of us.

Gods do not answer letters, John Updike wrote of the distant Ted Williams. Jerry Koosman will gladly entertain your queries and do so with a twinkle in his eye. So what if you’ve heard most of his stories before? They’re good stories.

Getting to those 20 wins also shouldn’t have taken so long. Kooz was in his ninth full season then. Maybe an extra win in his freshman campaign of 1968, when he posted a 19-12 record, beyond anything any Met (even Seaver) had ever compiled, would have lifted Kooz over some kid named Johnny Bench for National League Rookie of the Year honors. Maybe perception of a career that awed his teammates and opponents begins to shape differently with just a few more runs scored on his behalf. From 1973 through 1975, Jerry allowed not much more than three earned runs every nine innings and won exactly four more games than he lost. In ’76, he could have captured the Cy Young Award. His start was slower than that of his ultimately successful rival for the hardware, Randy Jones. Jerry finished hot, however: 12-4 in the second half, with an ERA of 1.64. Jerry was always a helluva finisher. Just look at that fifth game of the 1969 World Series. Gave up three runs in the third inning and brushed it and the Birds aside until Game Five ended with Jerry Grote literally catching Jerry Koosman.

Over 19 seasons with four different teams (the first dozen with us), Koosman built a viable Hall of Fame case. More than 200 wins. More than 2,500 strikeouts. A reputation as the guy batters didn’t care to face when something immense was on the line. Kooz’s case for Cooperstown didn’t so much fall short as get misfiled. The writers never saw it. Or they didn’t look — one ballot, four votes. The Mets installed him in their Hall of Fame in 1989, four years after he threw his final major league pitch. They then retreated to their secret conclave and emerged thirty years later [6] to announce 36 was worthy of hanging alongside 41 and 31, 14 and 37.

In talking to the media before his ceremonies and the fans during it, 78-year-old Jerry Koosman betrayed no impatience with the process. He was grateful and touched and embracing the moment. At the apex of our esteem for all he accomplished, he deflected our reverence by saying he just wished he could still fit in his uniform and start over again. To trot out the hoariest of sports clichés, he was just happy to be here.

I was happy he was there, too. You can’t wait forever on these things.