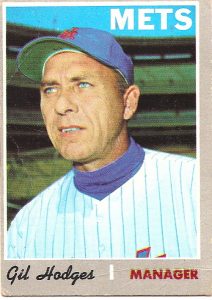

I no longer have to tell you why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame, and you no longer have to tell me why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame, and we no longer have to tell anybody why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame.

That’s because Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame [1].

Gil Hodges [2] is in the Hall of Fame. There are no better eight words a New York Mets fan could utter, no better eight words a Los Angeles or Brooklyn Dodgers fan could utter, no better eight words a Washington Senators fan could utter. Nobody who loves what baseball feels like when baseball is at its best could utter eight better words than Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame. My, that feels good to write, to say, to think, to know. For Joan Hodges, widowed nearly fifty years, living for this moment. For Gil Hodges, Jr., who has carried the responsibility of speaking for his father through so many disappointing selection processes. For everybody in the Hodges family. For everybody who feels like a not-so-distant relation to the Hodges family because of who Gil Hodges was, what Gil Hodges did and how Gil Hodges carried himself.

For the Mets who played under and with Gil and have sworn by his example and influence. For the Senators of the ’60s who got the first taste of Gil as a manager. For those Dodgers who’ve remained to tell their true-life tales of a peer they revered. For those wrote about him while he created a Hall of Fame candidacy via his actions and deeds. For those who continued to amplify and elaborate [3] his bona fides after he was gone. For those with whom he served overseas. For those who understood first-hand his generational legacy, whether they learned it in Petersburg, Indiana, or within (or proximate to) any of the five boroughs of New York City.

This is a great moment in the life of the National Pastime. This is what happens when the words keep flowing and the passion bubbles over and we don’t stop talking about why a man who transcended a specific honor deserved the honor nonetheless. We kept it up because it meant the world to so many in this world that he got it. And, at last, he did.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame.

As are, not incidentally, Buck O’Neil, Bud Fowler, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso and Tony Oliva. Six new plaques representing six people and six sets of stories whose impact on baseball was immeasurable in their day and for the years, decades and centuries that followed. O’Neil many of us met through Ken Burns. Once we met him, we would never forget him. We can never forget Fowler, who, like O’Neil, withstood the curse of institutional racism to play the game he loved. Miñoso came along much later than Fowler (1858-1913) and a little later than O’Neil (1911-2006), but not so late so that segregation didn’t unfairly separate his talents from what were considered the major leagues. Miñoso was a major player for the New York Cubans before having the opportunity to join the Cleveland Indians. His career coincided with that of Hodges and overlapped with those of Oliva — a preeminent hitter — an Kaat — a pitcher who succeeded at his craft for a quarter-century.

Every one among those six makes the Hall of Fame look good for hanging markers in their honor. The Hall would look even better with a few more from those its committees considered this year, but, as the 1969 Mets led to the promised land by Gil Hodges taught me when I was young, one miracle at a time.

It shouldn’t have taken what felt like a miracle for Gil to get in. He earned election through a big league playing career that extended from 1943 (before it detoured into World War II) to 1963 and was burnished by a managerial career that lasted from the moment he retired as a player until a heart attack felled him in 1972. He was the indispensable power-hitting cog of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ pennant factory, a plant whose production reached its peak on October 4, 1955. Hodges drove in the winning runs and cradled the last out on the afternoon the Dodgers became world champs [5]. Hodges was already Brooklyn’s favorite son, never mind that he was born and raised several states to the west. It was no accident he was in the first Opening Day lineup the Mets ever fielded. George Weiss and Casey Stengel knew that no matter who else they put on display at the Polo Grounds, fans from this National League town would come out to cheer for Gil.

Few hit more home runs or drove in more runs or better handled chances at first base when he played. Nobody inspired more loyalty when he managed. Think that’s hyperbole? His players are still loyal to him. Ballot after ballot, his name would appear for consideration, and ballot after ballot, the Swobodas and Shamskys and Seavers vouched for him. Vin Scully, who called Gil’s games in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, took the time as he approached his 94th birthday to author an essay [6] asserting that Gil needed to be selected this time. Mind you, Gil was selected in all but name almost thirty years ago. He got the support of the necessary number of votes in the 1993 Veterans Committee balloting, but one of those votes belonged to Roy Campanella, who phoned it in from a hospital bed. Ted Williams, the manager who had to follow in Hodges’s immensely popular footsteps in Washington, chaired that committee and, for reasons best known to him in those pre-virtual communications days, wouldn’t accept Campy’s call, or at least his vote.

That’s the sort of detail that had vexed us every winter Gil Hodges was eligible for selection. That and all those hundred-ribbie seasons that went disregarded; the 370 home runs that stood, when he belted his last, as the most by any righthanded National League slugger, yet had never impressed enough writers from 1969 to 1983; the three Gold Gloves that would have been more except they didn’t invent the award until Gil’s tenure as a player was more than half over; and the unforeseen, overwhelming success of the 1969 Mets, who didn’t show up in Gil’s statlines but reflected his contributions to the baseball landscape as well as any home run record reflects anybody’s achievements. All that plus the torrent of admiration for the man and the absolute lack of criticism beyond analytical esoterica. His Wins Above Replacement could be debated if that was your bag. His character was unimpeachable.

As noted, we don’t have to do this part any longer. We don’t have to state Gil’s qualifications for Cooperstown. They are about to be etched on a plaque for everybody to see. We can travel upstate if we choose and read it for ourselves. We can simply know it’s there and feel good that the right thing sometimes eventually happens.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame. I know you know that, but I really do enjoy typing it.

The literary subgenre devoted to articulating Gil’s credentials for Cooperstown now goes out of business, but if it had to take more than a half-century to finally elect this worthiest of candidates, I’m glad that the wait lasted just long enough to include this marvelous piece of research, reporting and writing rendered by Friend of FAFIF James Schapiro. Treat yourself to what amounts to the closing argument [3] on behalf of Gil Hodges for the Hall of Fame.