Later this week I’ll be along with the Tenth Annual awarding of the Oscar’s Caps, recognizing the year in Mets Pop Culture. But one Mets pop culture sighting in particular was too big to confine to a sentence or paragraph amid a catalogue of other, albeit worthy sightings (all Mets pop culture sightings are worthy), so we’re going to dwell on it by itself here for a spell. And we’re going to start, as the Mets did in 681 regular-season games during the 1980s, by leading off with Mookie Wilson.

Mookie Wilson has never seen Do The Right Thing, at least he hadn’t when the Los Angeles Times asked him about it for a story regarding Mookie Blaylock joining the Dodgers. Most every high-profile Mookie came up, including the Mookie director/star Spike Lee played in his landmark 1989 film. “I’m not a moviegoer,” Wilson told LZ Granderson. “I heard people talk about it and I know it’s Spike Lee and he’s from New York, but I haven’t seen it yet. I have no idea if he named the character after me, but it sure seems that way, doesn’t it? I’m sure there were Mookies before me, but I didn’t know of any…definitely not one who was doing the things I was doing when I was playing. It’s just one of those funny timing things, I guess.”

Funny timing, says Mookie? The L.A. Times article appeared on February 11, 2020, five days after I met the Mets fan who a) would soon be spending a decent amount of time himself speaking with Mookie Wilson and b) when asked if he has a particular favorite Metsian pop culture moment, replied, “I love that Spike Lee’s character was named Mookie.”

Timing says the Mookie who delivered pizza in Bed-Stuy while wearing Jackie Robinson’s 42 and called out hypocrisy when it stared him in the face in the summer of 1989 was not only trying to do the right thing, but he was in the right place at the right time. Mookie Wilson was in his tenth and final season as a New York Met. The New York Mets were in their sixth of seven seasons as a National League East powerhouse. The Mets of the era were a totem Spike latched onto while making or promoting movies during this period — TV appearances, trailers, dialogue or background in at least three features. Meanwhile, the nearby New Jersey Nets had just drafted, in June of ’89, Mookie Blaylock, pretty much the second (or third, depending on when you went to see the movie if you were a moviegoer) Mookie most folks had heard of. Wilson would be traded to Toronto by August and propel the Blue Jays to the playoffs, making Mookie an icon in two nations, but he’d retire from baseball in 1991 and inevitably fade a bit from the collective consciousness outside of Flushing.

Our Mookie was no longer the Mookie who leapt universally to mind when you mentioned a Mookie as the 1990s rolled on and the 21st century was born. He was for us, of course, but Blaylock would have his day in the sun as a 13-year NBA guard (and brief moniker for Pearl Jam before Pearl Jam was Pearl Jam); Lee’s film with its lead character maintained enormous cultural staying power; and then, in 2014, came All-Star-to-be Mookie Betts, and all wagers were off as to whom a later generation would point as the Mookie of record. When he was a Red Sox rookie, the newest Mookie — Markus by birth — explained his parents started calling him by that nickname from watching the Mookie who played basketball, not baseball.

But the guy I met in person on February 6, 2020, a New York-bred movie director in his own right, has done his best to keep the original Mookie atop the Mookie marquee — even if William Hayward Wilson wasn’t necessarily the lead character in his screen gem.

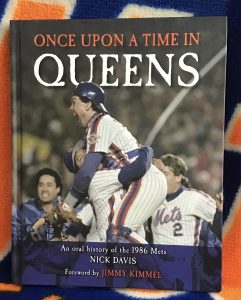

Nick Davis is the auteur behind Once Upon A Time in Queens, the four-part film documenting the ascent and ascendancy of the 1986 New York Mets, how they rose from the ashes of the lowest point in franchise history nine years prior to reach the heights of the baseball world for a moment that both ended too soon and lasts to this day. Soaring in approximate tandem with the ballclub was the city it represented. When we met New York at the outset of Davis’s story as it aired on ESPN as part of the 30 for 30 series in September, it was still smoldering from the great blackout of the night before, July 13, 1977, a Wednesday that clocked in exactly four weeks after June 15, 1977, the aforementioned franchise low point for the Mets.

New York was in rough shape that summer. The Mets’ shape was rougher. Tom Seaver was traded. Dave Kingman was traded. Last place was held on a long-term lease. And rooting for the Mets, despite M. Donald Grant doing the wrong thing, were kids like Nick Davis in Manhattan and me on Long Island. We didn’t know each other then, but we might as well have been each other. Every Mets fan of a certain age in the late 1970s was, when it came to the object of our baseball affections, determined to do the unpopular thing. We were all one. We were all alone. We couldn’t imagine there were any longer many of us constituting us.

We’d rooted for the Mets before Seaver was traded. We’d keep rooting for the Mets after Seaver was traded. We’d hope for the best. The hoping was laced with waiting, because there was a ton of waiting to be done. The Mets were down and were not getting up in 1977. Or 1978. Or 1979. A glint of light shone through in 1980 — the franchise was sold, a Magical slogan fleetingly resonated — but prone remained the default position for the Mets. As it did in 1981. And 1982. And well into 1983. Every one of those years lasted no more than 366 days and every one of its baseball seasons no more than 163 games (I’m a stickler for counting ties), but if you were Nick or me or perhaps you, every minute when the Mets were dismal and we were sure there were hardly any other Mets fans besides our hardy handful, lasted an eternity.

Then eternity turned around. You say “1983” differently from the years that immediately preceded it, last place or not. Then you say “1984” and “1985” and it’s an entirely new ballgame. Which gets us to 1986 and the rest of the story Nick had in his bones and was ready to cinematically spill by 2020.

Which is what got Nick and me together face-to-face for the first time that February. We had been in touch via e-mail and phone in the months prior as Nick, a faithful FAFIF reader for a few years to that point, let me in on this project he was working on about the 1986 Mets and asked if I would I like to be, in Ken Burns’ The Civil War terms, his documentary’s Shelby Foote, its voice of historical perspective.

He had me at “1986”.

I never watched The Civil War, but got what Nick meant. The difference between the epic battle for the American soul and the Mets marching through the National League East, it would occur to me later, was Burns couldn’t interview the principals who were around from 1861 to 1865. Davis would have access to plenty of alive & well veterans of the Mets of the 1980s, no matter how astounding it is that so many of them had survived to 2020 despite putting their minds and bodies through the wringer way back when. But there was a role for me, nonetheless. I was the guy who — with no cameras rolling — paced around his living room late at night when not sleepy and talked to myself about the Mets, usually while a cat ignored me. Not just about the 1986 Mets, but surely a lot about those halcyon days. They represent the Mets’ most recent world championship, you might have heard.

I’m also the guy who, unlike so many real-life characters testifying in Once Upon a Time in Queens, went back to my room, so to speak, after the final out. The 1980s in New York on display in Nick’s movie was one I knew about from a distance of an hour by train and 180 degrees by inclination. Maybe I’d go out for a couple of beers with my friends on a Saturday night, but not until Jesse or Roger nailed down the latest win (if, in fact, somebody didn’t pitch a complete game). That was about it for my nightlife. My priorities in 1986 were pretty much the priorities that would remain my priorities. My memory of the Mets leading up to and all throughout 1986 was intact. The recollections I relished recalling to myself remained accurate and vivid. Nick, sensing this was who I was and what I remembered, invited me to sit in front of a camera in somebody else’s living room that was doubling as a documentary set.

I was asked to keep my involvement quiet because the project had not yet been officially, officially been signed off on by its eventual network partner. After I spent what turned into a very long day in that other living room, somewhere in Crown Heights, I dutifully bit my tongue. The pandemic would fully hit a month later, so the interview between Nick and me lingered as The Last Fun Thing I Did outside the house for quite a while, yet could tell nobody about. Once it was announced as set to air on ESPN and had been given its name, I was delighted to mention to others that it would be on but felt reluctant to make too much of a personal to-do about my being included. Pop Culture Week here is my excuse to more than whisper about it.

Nick’s framing device notwithstanding, I wasn’t Shelby Foote. And I wasn’t Mookie Wilson or any of the actual 1986 Mets who were going to make this thing fun for everybody who watched it. I’d be me, though, and that would have a purpose. I’d be what Nick called “foundational,” the head talking with first-person plural affinity for the subject — we/us/our are my Met pronouns — but with the remove of someone who understood he was not a player, but a fan. Fan with benefits, you might say, activating my fan superpower of delineating between what a moment felt like one veritable minute before the moment changed. I’ve watched a lot of Mets, I’ve read a lot of Mets, I’ve written a lot of Mets and I remember a lot of Mets. If that adds up to a hint of authority judged valuable enough to contribute a little foundation to what would become the definitive retrospective on the most spectacular team in New York Mets history, ask away. I’ll give you what I’ve got in complete sentences. I won’t pretend to know what I don’t.

When I arrived at the house in Brooklyn where the filming would commence, I assumed I was the eleven o’clock appointment, with other Shelby Footes, or perhaps Shelby Feete, slated for 1:30 and 4:00. There was a large crew and loads of equipment. I’d done other talking-head shoots over the years, but never with this much heft to it. They were set up for one interview, however. Just me. I was also the first project-dedicated interview they had scheduled overall (though Nick had the foresight to grab the opportunity to record a 1986-themed chat with a fellow named Roger Angell a couple of summers before). I think I was sort of the guinea pig for how they planned pre-pandemic to go about approaching other sessions.

The day boiled down to two people talking and a lot of people preserving it. Camera person. Light person. Sound person. Persons of job titles I couldn’t tell you, but everybody who had taken over this handsome house in Crown Heights was a stone pro at what they did. They put such care into the shooting. The windows were covered so thoroughly that there was less light coming into our set than there was Shea Stadium before de Roulet sold to Doubleday. If a car rumbled down the street, “cut!” might be ordered. And this was all so Nick could ask me to talk about what it was like when Darryl Strawberry was called up to the majors.

It was an exhausting late morning, afternoon and early evening, but exhausting in the extra-inning doubleheader-sweep sense. You want to be exhausted by something like that. Without even knowing COVID was about to wreak havoc, I couldn’t have asked for a more fun Last Fun Thing. It was work for the crew. It was work for Nick (during our lunch break he learned George Foster was declining a chance to participate). It was a blast for me. Somebody who truly cared was asking me to meander through Mets history, a little in 1962 and 1969; then to dig into the dark times without fear; and then, as my reward for reliving our state of Seaverlessness, to come out of the tunnel on Field Level, with Darryl and Keith and Doc and Kid waiting to greet me on the other side.

To get from where kids like Nick and me sat, nursing our Wednesday Night Massacre wounds from June 15, 1977, to the top of the mountain on October 27, 1986 (and the crush of parade humanity I threw myself into downtown the next day) was what being a Mets was all about in the time span covered by Once Upon a Time in Queens. Someday it would stop hurting so much. Someday it would stop sucking so much. Someday we wouldn’t be practically the only Mets fans we knew. Someday we’d have the best young player in the game and the best pitcher of any age in the game plus a couple of superstars we used to root against because they were always beating us when they were a Cardinal and an Expo, but somehow they’d become ours. Hell yes, I’m down to talk about those Mets days all day in somebody else’s living room. I’d do it with almost anybody. But I couldn’t have asked for a better Mets fan to do it with than Nick Davis.

Nick and his editors took my interview and a few dozen other interviews — whose logistics might have been hampered by COVID, but the impact of their content went unharmed — and a torrent of period footage and game footage and created four incandescent hours. His original cut clocked in closer to seven. I would have watched that many, but the four minus commercials that made it to air take care of their business beautifully.

There’s New York after the blackout. There’s Sergio Ferrer not reaching base. There’s Nelson Doubleday and Frank Cashen coming into our lives. There’s Keith Hernandez going deep and personal. There’s the throbbing nightlife in which Mets would indulge but to which they would not (yet) succumb. There are National League opponents who would succumb to the Mets. There’s Lenny Dykstra worming his way back into our hearts. There’s two people I know who sent in their own “here’s where I was” stories from Game Six — the second Game Six — when Nick put out an APB for fan anecdotes. There’s Kevin Mitchell crooning. There are snippets from local news and other evidence of how we consumed the ’70s and ’80s. (One of my kibbitzing suggestions — a clip I recalled of Johnny Carson poking fun at Dodger World Series goat Bill Buckner in 1974 — wound up just missing the final cut, much as John Gibbons would be the last player removed from the postseason roster a dozen years later.)

All of this was for the Mets. All of this was for us. The 1986 Mets earned themselves and us this treatment. Nick and I wouldn’t have guessed it was possible in 1977 and 1978 and so on that a Mets team could or would. Nick, like me, savors Mets pop culture sightings. He treasures, as he did as a kid, any evidence that the Mets exist anywhere outside the basement of the NL East. “It always makes me very happy and feel very seen when the Mets enter pop culture, because there was this period when we were so bad,” he told me when we last spoke, right before Thanksgiving, “Those years, coming of age as a fan between the Seaver trade and 1983, it was just so bleak, and any time at all that they entered the national conversation, it was just thrilling. You were just clinging to these things where they’d get to be on Monday Night Baseball or Mazzilli would hit a home run in the All-Star Game, it was like, ‘Oh my god!’ [and] ‘Hey, we’re in the major leagues, too!’”

Then Nick allowed himself a 42-year-old gripe that “of course they’re not gonna give him the MVP because somebody made a good throw from right field,” because Nick, like me, was a Mets fan in 1979 and that inner Mets fan from 1979 is always going to be a little bit bitter about Dave Parker being voted hardware that could have just as easily gone to Lee Mazzilli.

I theorized to Nick that being from New York probably makes us a touch myopic in our thinking that our two world championships are absolutely among the two biggest World Series achievements in baseball history. Well, he replied in so many words, it is New York, no doubt gaining him fans in the so-called heartland. I asked him if he thought he could make the same sort of film if ESPN or MLB came to him and proposed that Minneapolis in 1987, especially but not only the Twins, really symbolized something enormous about their moment. They, after all, won a World Series some 35 years ago, just like the Mets (then, unlike the Mets, won a second a few years later). Nick played along — Prince, Paisley Park and the Minneapolis sound were certainly influential, he reasoned — but maybe “Kent Hrbek, for all his wondrous qualities,” wouldn’t resonate for multiple hours for a national audience as a testament to his times.

I might not be as invested in it if I weren’t in it, but I believe that no matter my involvement, Once Upon a Time in Queens emerged on ESPN not only as compelling and entertaining but as Met canon. It’s going to be embroidered into the telling of our larger story the way Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? and The Bad Guys Won and The Worst Team Money Can Buy are. Hell, it could be up there with Kiner’s Korner. There’ve been other programs and films that have examined 1986, enough that the reflex reaction to this one might have been, “what, another?” but this one is the one you put in the time capsule for all time, right alongside your VHS copy of the presciently titled A Year to Remember. The way we saw the 1986 Mets in Once Upon a Time in Queens will define how we remember that year — especially for Mets fans who weren’t lucky enough to experience the 1986 Mets first-hand.

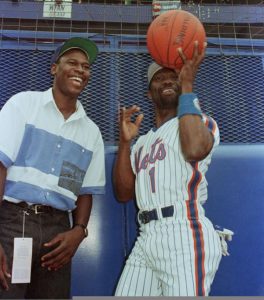

The first time I saw Nick in person after our day on the set in Brooklyn was September 3, 2021, at Citi Field, the evening he publicly screened the first two hours of the movie. The first thing he asked me with no cameras recording us was whether I thought we still had a chance to win the division. Yeah, we were still essentially the same person. Mookie Wilson was also there, joining Nick and Bobby Ojeda in a little pre-movie Q&A conducted by Colin Cosell. This was a movie Mookie didn’t mind going to see. He and Bobby O, much the way their 1969 world champion predecessors do, confirmed that Mets fans never get tired of bringing up their exploits to them. It’s fair to say they don’t mind the attention. Mookie, however, implored us to not live in the past — except when it came to remembering him, in which case, he was OK with it.

As were we in the crowd once CitiVision lit up with parts one and two and when we tuned in a couple of weeks later to take in the entire production on ESPN. My god, Nick and his crew captured those Mets and those times. At first, I looked for myself on the screen. Then I basically forgot I was in it because I was too caught up in the story and the sound (Tears for Fears was never put to better use). I’ll take the word of the likes of Tama Janowitz and Chuck D for what New York c. 1986 was like after dark, away from Shea. I worked in the city then, but took the LIRR home by sunset. If it was baseball season, I wanted to get myself in front of a television by 7:35. Kurt Andersen was capable of putting the raised financial stakes of the Go-Go Eighties in context without my two cents, which is roughly what I had relative to the “Greed is Good” goons down on Wall Street. The only place I aspired to go-go was to an occasional game.

The reach of Once Upon a Time in Queens was staggering in that my sister watched the whole thing, and not just because her brother was in it. After the first installment, she wanted to tell me what a thrill it was to see me on television. After the fourth, she demanded to know why the Mets would ever trade Kevin Mitchell. She wasn’t asking me such questions in 1986.

Talk about feeling seen. I heard from my doctor, who is not a baseball fan; he saw me in a commercial and bragged on it to his other Mets fan patients (uh, confidentiality?). I heard from my mechanic, who is not a Mets fan, but he takes good care of my ancient car, so I’m respectful of Gerrit Cole when we’re not talking brake lines. I heard from a guy who was one of the few determined souls I knew in high school who stuck with the Mets. I’m pretty certain we hadn’t spoken since 1986. He saw me in this. I was grateful to connect again. I was grateful to all who said they enjoyed seeing or hearing me in it. I’m glad, quite frankly, that I never ran across any criticism of a “who the bleep is Greg Prince and why is he on there instead of so-and-so?” nature.

When I caught up with Nick in late November to ask him how it all felt now that it was done and so many had seen the result of all the work he put in, he reminded me I was on his get-list all along. He couldn’t get every player he wanted, but he had no problem getting me. When I asked, ostensibly on behalf of my curious sister, why the background for my segments was so dark that the bookshelves in the background weren’t visible (I wondered if my lack of telegenicism had to be compensated for, or if a network suit urged my face be obscured as much as possible), he explained the choice: “This man has the weight of Mets history behind him.” I’ll buy that.

I also bought the highly worthwhile companion volume to Once Upon a Time in Queens, an oral history version of the same time period with much the same cast as the documentary. Leafing through it, it hit me just how amazing it is that I somehow slipped into what stands as the definitive retelling of 1986. Being on TV was indeed a fun thing. Print is where I live. On page 79 of the book, there is a string of remembrances that are from, in capital letters, BOBBY OJEDA, WALLY BACKMAN, DWIGHT GOODEN, GREG PRINCE and DARRYL STRAWBERRY, as if Bobby, Wally Doc, Darryl and I always hung out together.

I blush just thinking about it.

Well, now I’m definitely going to have to see it. A, because you’re in it, and B, because the Met fan childhood you describe was my childhood. Maybe more so in my case, because I became a Met fan in 1977, so I never got to see the good years before. Competing for a title (never mind winning one) was so alien to my fan consciousness that when it happened it was somewhat akin to living a fairy tale. If this film captures the fairy tale, I certainly want to see it.

It’s a great film, and so interesting to hear a little of how the sausage was made.

Hard to believe June 15, 1977 to October 27, 1986 was only 9-1/2 years, but seems like different universes.

Greg – I only started watching this with my wife last night, but you look and sound great!

When this aired in September, I though I would hold off on watching until the darkest part of the baseball calendar and I’m glad I did. Looking forward to parts 3 & 4 tonight.

Some thoughts since I’m writing…

1. Dykstra seems to get progressively worse as things go on. I guess that’s true to life.

2. So far, George Foster is looking far more beloved than I remember him being in the first half of 1986…

3. Billy Bean is cool. He deserved to be on that team in retrospect.

4. I’m watching with my wife who only became a Met fan when we started dating in 2012. For me, these are fond memories of NY and the Mets. For her, what a great history lesson.

I watched it when it was on originally, and it was the most interesting show I have ever seen.

And this from a guy who, in retrospect, is not a big fan of that team because they underachieved mightily in the few years after.

But I was sure a maniacal fan of the team at the time, of course!

I went to the parade, and I remember seeing Darling, but it might have actually been someone else with big hair (anyone).

Greg:

Wow. This is quite an entry.

I cannot thank you enough for your kind words about the film. Making this, as I am sure you know, was the greatest joy of my professional life, and I continue to regard asking you to sit for that first interview as one of the really good decisions that got the ball rolling in the right direction. (To be honest, I knew from at least as far back as 2017 that I wanted to interview you for this project…)

Thank you again for your “foundational” participation – everything from Sergio Ferrer’s 1979 to how New Yorkers show love at a parade (dumping garbage on people), you really were OUR voice throughout – and for continuing to do what it is that you do for all of us.

And yes, I think one more starting pitcher, and we are on our way in 2022.

LGM,

Nick

I’m a permanent Mets fan and a baseball and sports fan at all because of the 1986 Mets. I might bandwagon other NYC area teams when they’re hot, but the Mets are the only team I follow ardently for better or worse.

I was a young child in 1986 growing up in a family with zero sports fandom. The 1986 Mets experience was formative.

One of my most vivid memories from childhood is deliriously yelling “Let’s go Mets!” out the school bus window with my classmates during the ’86 run.

As far as other teams during the Mets mid-80s run that could have made a similar impression at least on a national level, I think the Cardinals’ distinctive style of play could have had that kind of impact if they had won a championship or two.

[…] As long as 1986 has come up, let us note the back-in-the-day releases of the twelve-inch singles “Get Metsmerized” and “Let’s Go Mets” along with the visit of Roger McDowell and Lenny Dykstra to the MTV set, where Dykstra hit on VJ Martha Quinn, a little more than 35 years ago. All of this was featured in the Nick Davis opus Once Upon a Time in Queens, the Mets Pop Culture event of 2021. It was written about in some detail here. […]