Baseball said goodbye this week to 83-year-old Tommy Davis, the two-time National League batting champ, the RBI king whose 153 in 1962 were the most in the NL in 25 years and would be the most in the NL for another 36 years, and the first American League hitter to make the most out of being designated on a daily basis (as an O, he was the only regular DH to crack .300 in the unfortunate experiment’s first year of 1973). There were any number of angles from which fans could remember and appreciate Davis and the career that encompassed 18 seasons spent with 10 teams.

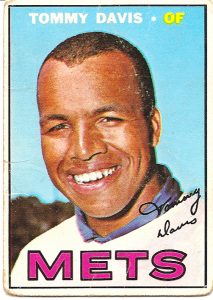

I remember Tommy Davis as my gateway Met — his 1967 Topps card may very well have been the first picture I ever held in my hands where the word “METS” caught my attention — and I appreciate him for that. It doesn’t matter that by the time I understood what the Mets were and that I couldn’t live without them Tommy was no longer among them. It didn’t matter that once I had a little actual fandom under my belt and circled back to my 1967 Tommy Davis card I discerned he wasn’t wearing any item of clothing with a Mets or New York insignia. Not so much as a pinstripe was in evidence. Topps knew how to take a picture of a ballplayer from the shoulders up, hat removed, just in case that ballplayer moved on from where he was being photographed.

But I didn’t know that when I initially encountered Tommy Davis of the METS. The card said he was part of the outfit for which I was developing the first flickers of affinity. The jerseys and caps I’d latch onto later. For now, “METS” sufficed to entice me, with Tommy Davis their smiling emissary to a child who wanted in on whatever was making this man on the card appear so gosh darn happy.

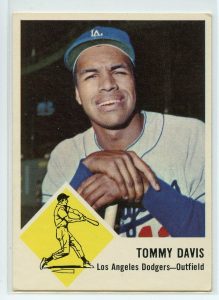

The Mets were Davis’s second major league stop. He was a kid from Brooklyn, an alumnus of Boys High, Class of ’56, who did what any boy from Bed-Stuy might have done if given the opportunity at the time: He signed with the Dodgers. In those pre-amateur draft days, he was pursued by more than one club. Recruiting on the home team’s behalf was Jackie Robinson. The kid from Brooklyn was swayed.

Unfortunately, the team from Brooklyn picked up stakes and moved to Los Angeles. Davis’s debut came toward the end of L.A.’s first West Coast pennant race as a fourth-inning pinch-hitter in St. Louis. It was a wild game. Tommy was batting in place of Clem Labine, who was Walter Alston’s third pitcher of the night (his first was Sandy Koufax, who gave up four runs in two-thirds of an inning). The youngster struck out in what became an 11-10 Los Angeles loss. The Dodgers recovered to reach and win the 1959 World Series.

Davis kept moving up, too, breaking through as an outfielder who’d force his way into the Dodger lineup any way he could, starting as many as 59 games at third base in a season. The OF-3B experiment didn’t really take, as Davis remembered for his SABR biographers Paul Hirsch and Mark Stewart, “They never really explained to me how you had to short-arm the ball at third. I was throwing it like an outfielder and the ball was sailing over Hodges’s head.” That bat of his would play anywhere, though, and it looked like a sure bet to be on display in the 1962 World Series. The Dodgers had developed a star-studded cast worthy of the Hollywood glitterati that flocked to their new stadium. Maury Wills was shattering stolen base records. Don Drysdale was winning 25 games. Sandy Koufax was being Sandy Koufax (no-hitting the infant Mets along the way, almost literally taking candy from a baby). Big Frank Howard busted out with his first 30-plus home run season. And knocking everybody in, not to mention every pitch he saw, was Tommy Davis.

Tommy was “probably the best pure hitter I ever saw,” Dodger broadcaster Jerry Doggett recalled three decades later for author David Plaut. “A great clutch hitter,” teammate Ed Roebuck attested. Koufax took notice, too: “Every time there was a man on base, he’d knock him in. And every time there were two men on base, he’d hit a double and knock them both in.”

“When I see those ribbies on the bases,” Davis confirmed, “it means more money in the bank. When I see men, I see ’em as dollar signs.” Whichever teller handled Tommy’s account was kept extraordinarily busy in 1962. Let us repeat that runs batted in total: 153. It was a sum unheard of in the senior circuit since the 1937 peak of Joe “Ducky” Medwick and not surpassed again until Sammy Sosa did it in 1998. Davis’s batting average smoldered at .346, on 230 base hits, a figure not reached in the NL since Stan Musial in 1948 and not topped since Medwick in 1937. The Dodgers rode Tommy’s bat to a first-place lead that looked impenetrable. After 149 games, the Dodgers led the Giants by four games. The Dodgers turned cold immediately thereafter, however, allowing their rivals to catch them at the finish line and force a three-game playoff that echoed the New York-Brooklyn dynamic of eleven Septembers earlier. Now, with the foes having morphed into San Franciscans and Los Angelenos, history repeated itself, with the transplanted Jints sticking it to the uprooted Bums in trademark dramatic fashion.

Down a stretch that lives in the same tier of Dodger infamy where 1951’s resides, Tommy Davis, from Game 150 through Game 165 (that playoff set counted as a regular-season series), hit .394 and drove in 14 runs. He didn’t get the MVP — Wills’ 104 steals were too obviously history-making; and he didn’t go to the Fall Classic — Willie Mays led the Giants there with his own Most Valuable-caliber campaign (49 homers and 141 RBIs not to mention being Willie Mays in center field); but Davis could lay as much claim

to 1962 as anybody this side of Casey Stengel.

To say Davis would never repeat 1962 is to say nothing that diminishes the rest of his career. If 230 base hits and 153 RBIs were easy to replicate, they would have been garnered far more often by many others. Tommy’s 1963 encore was good for another batting crown (.326) and a no-doubt pennant en route to a four-game sweep of the Yankees in the World Series, a World Series that saw Davis lead all hitters with a .400 average.

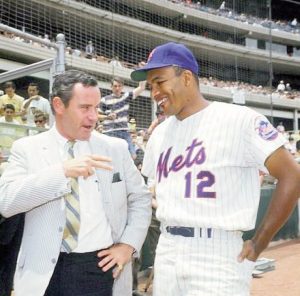

Tommy Davis was at the top of the baseball world in the fall of ’63. Three years later, a span that included a gruesome broken ankle that derailed his prime, he’d be traded to the Mets. The Dodgers won the 1965 World Series without him and another flag in 1966 with him (when he batted .313 in 100 post-injury games). They were the Dodgers, the flagship name in their sport, whereas the Mets were…you know, the Mets. His stock had plummeted, à la John Olerud’s on his trip from Toronto batting and world champ to suddenly a Met in the mid-’90s. But coming to the Mets was OK by Davis, because it meant he was coming home. When he was asked about such a trade in theory, while still at work in Southern California, Tommy wasn’t reticent to embrace the notion — a geographic inverse of the sentiment that would frame Darryl Strawberry in a less than glowing light in 1988: “I love New York,” he told a couple of reporters from back east who were visiting Dodger Stadium in the midst of that last L.A. pennant chase. (He also maintained a special rapport with the gentlemen of the press from the media capital of the world. As George Vecsey recalled this week, “As soon as he sighted familiar faces — or heard familiar Noo Yawk accents — Tommy would turn to his teammates and announce, ‘Hey, these guys are from my hometown.’”)

If you believe in reasonably happy endings, the second stop of Tommy Davis’s baseball career should have been his last, or at least among his longest. Kid from Brooklyn, now an older/wiser veteran, setting up shop in Queens. He can still hit. He can tutor the outfielders of the Youth of America Cleon Jones and Ron Swoboda. The Mets climbed all the way to ninth place in 1966. Would it be too much to ask that fate position Davis and the Mets in harmonic convergence as the Mets reach for the moon, with Tommy guiding his juniors on their lunar mission?

Yeah, it would be. If things worked poetically, the main Met traded to the Dodgers to get Davis, Ron Hunt (who went west with Jim Hickman), would have stayed a Met long enough to help directly instigate 1969. Hunt was the Mets’ first more or less homegrown star. Hunt was supposed to be a harbinger of truly better times ahead, not sent away when 95 losses represented vast improvement. But Wes Westrum wasn’t as crazy about Hunt as Stengel had been and Alston was never too crazy about Davis and the deal got made shortly after Thanksgiving weekend of ’66.

“New York is my hometown and I’ve always loved the fans,” is how Tommy greeted the news. “My mother still lives in Brooklyn and all my relatives have been calling her and congratulating her that I’m coming home. So you’ll see I’ll be playing in familiar surroundings.”

Local Huntlessness notwithstanding, Davis’s return to the five boroughs — he was a lifetime .389 hitter in 54 Shea Stadium ABs and something about the baseball cards of his that were shot at the Polo Grounds always looked just right — made so much sense. As George Vecsey speculated in Newsday, this new acquisition “could be a solid hitter for the Mets, who have never had a solid hitter.” The Mets had been in business five years. It wasn’t much of an exaggeration.

“Davis will be in left field and he’ll play every day,” Westrum announced, offering Tommy a better deal than he was receiving in L.A. under Alston. “I can’t hit unless I play regularly,” had been Davis’s gripe (shared by most players). Now, on a new team and taking stock of the homey atmosphere, Tommy added, “I expect to go the full season and play to my capacity.” By Spring Training, he was also ready to fill that ideal role of veteran mentor, telling Jim Selman of the Tampa Tribune he liked what he was seeing from his fellow Met outfielders, “I see a lot of potential here. Take Cleon Jones. […] Ron Swoboda hits the ball good. If Jones and Swoboda can improve their fielding, they could be 10-year men.”

Westrum indeed played Davis regularly and Davis returned the Met manager’s confidence by going the full season and playing to his capacity. In 154 games — 149 of them as the starting left fielder, Tommy batted .302. Only Ron Hunt in his All-Star starting season of 1964 (.303) had topped him among Mets with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title. Davis’s 73 RBIs were the third-best by any Met to date, bettered only by Frank Thomas’s 94 in ’62 and Joe Christopher’s 76. His 16 home runs led the 1967 Mets, whose most satisfying victory among 61 may have been the May night when Jack Fisher went 11 innings for a complete game W captured in walkoff fashion by Tommy Davis’s walkoff dinger. No Met pitcher had ever gone longer in service a route-going triumph, and no Met pitcher would ever go longer and be rewarded with a win. Yet Fisher couldn’t have been any more satisfied than Davis after he crossed home plate at Shea Stadium to beat the Reds.

“This,” he said, “is the first time I’ve had anything to cheer about since 1963.”

All of what Davis did in 1967 wasn’t enough to keep the Mets from sliding back into the basement and nothing the Mets could do, including promoting Rookie of the Year Tom Seaver, was enough to keep Wes Westrum from resigning in September before he’d find himself fired, but the comeback performance got some BBWAA member’s attention, because when the MVP voting came out after the season, Tommy Davis landed in eighth place on one writer’s ballot. It was a far cry from the 20 first-place votes Orlando Cepeda attracted in winning the award unanimously, but the tenth-place Mets finished 40 games behind Cepeda’s eventual world champion Cardinals. As small miracles go, Davis emerging from a severe ankle injury in ’65 and Walt Alston’s afterthoughts in ’66 to gain mention among the most valuable players in the National League in ’67 for a ballclub whose record nobody much valued rates as more than a footnote.

So does Tommy Davis’s one year as a Met. One year was all it was, but it was a very complete year in a very specific sense. Fifty or so players have been Mets for exactly one season. That is one season from Opening Day to Closing Day, no demotions to the minors, no time on the DL/IL, no military service, not even paternity or bereavement leave. They were brought up or brought in; they did their part for the orange and blue to their capacity, as Davis put it prior to 1967; and then, for one reason or another, they were gone. The reason was usually the business of baseball. In Davis’s case, the business was about filling center field, a void that during the 1960s vexed the Mets the way catcher did until Jerry Grote and third base until…well, that would vex on and off for a while.

Despite Davis’s rock-solid presence in left for six months, the 1967 Mets were a team in flux. They used 54 players, the most they’d use in a single season until 2018. Their manager, as noted, quit. Their general manager, the skilled Bing Devine, longed for home in St. Louis, sort of the way Davis had for home in New York. Executives had more agency than players. Before Devine departed, he laid the groundwork for a trade very much meeting with the approval of the new and highly valued manager of the Mets, Gil Hodges (the same Hodges to whom Davis had trouble throwing accurately when they were corner infielders together in L.A. early in the decade).

Gil Hodges very much wanted Tommie Agee in center field. He’d seen him look dashing in the American League, when Hodges managed the Senators and Agee flashed onto the scene for the White Sox. Chicago was willing to give up on Agee, the 1966 AL Rookie of the Year, because of his perceived offensive shortcomings after the Sox fell shy of the pennant in ’67. “The first thing Hodges wanted to do when he became manager,” Johnny Murphy, who succeeded Devine as Met GM, explained. “was to acquire Tommie Agee. He wanted a guy to bat leadoff with speed and that could hit for power. He also…needed a guy in center to run the ball down.” This was in the wake of one more Met center field experiment — the briefly ballyhooed Don Bosch — deteriorating on contact. Bosch started in center on Opening Day 1967, keeping the job for 15 of the Mets’ first 20 games, the 20th of which was on May 4. He’d get three more starts out there over the next month and then disappear from the lineup until September. Bosch’s batting average for the season (when he wasn’t shuttled to Jacksonville) was .140. So, yeah, the Mets were still keeping an eye peeled.

“We had to plug the hole in center field,” Murphy elaborated. “We’ve never had a center fielder. We’ve tried to develop our own and to trade for one, but we have never had any success. Now we’re getting a fellow we know can field and run and hit for power.” It was nothing personal toward Davis that as the best chip the Mets were willing to exchange, he was gonna be the outfielder the White Sox would get back. “Tommy did a good job,” Murphy affirmed. “Nobody here is mad at him. He played hard, and he played twice as many games as anyone expected. We simply are dealing for a need, a center fielder.”

The trade went down in December: Davis, Fisher, pitcher Billy Wynne and catcher Buddy Booker for Agee and infielder Al Weis. If you’ve read this far, you know the trade worked out spectacularly for the Mets. Agee had a rough 1968 but a transcendent 1969. Jones, who moved over to left, blossomed, too. Swoboda may not have had quite as long a career in store as Davis predicted for him (only nine years in the bigs), but boy, was he about to have his moments. The miracle these outfielders and their teammates — very much including Weis with his .455 World Series batting average — would overshadow essentially all of the incremental progress the Mets who didn’t make it to the mountaintop with them had forged. The Mets’ story, unless you were willing to get granular, was they were born a laughingstock; they languished; and then, as if out of nowhere, they rose to an apex unmatched in the annals of human achievement.

I’m fairly comfortable with that story in broad strokes, but granularity and the knowledge that the 1969 Mets didn’t exactly come out of nowhere has its appeal. I wasn’t watching in 1962; Channel 9 didn’t air in utero. I missed the extended infancy and toddler years. But sometime before fully discovering the Mets, perhaps when I was four, maybe five, I shuffled through my older sister’s short stack of baseball cards and decided Tommy Davis and METS were for me. As would be the cards once she grew bored with them. Maybe I’ll never fully appreciate how futile the Mets felt prior to 1969, but I’d like to think I can appreciate that there were Mets prior to 1969, and some of them, like Tommy Davis, left their mark on their times as best they could.

Could have the Mets won their division, their pennant and their world championship without Tommie Agee and Al Weis? It’s never occurred to me to ask. Why would I want the Mets to have been one iota different from what they were when they were at their most miraculous? Yet a person who’s familiarized himself after the fact with the Mets from when they attempted to master the conversion of their unsteady crawling skills into walking does wish, with loads of hindsight, that somehow Tommy Davis could have stuck around a little longer and been a part of 1969 and 1970 and kept being at home in New York (this same person also wishes Ron Hunt could have enjoyed the fruits of what his pre-trade contributions sowed, yet there’s not an alternate timeline handy that will accomplish every ancillary wish). Tommy joked more than once that because he played such an intrinsic role in building the ’69 roster, maybe the Mets should have awarded him something like half a World Series ring. “You’d think the Mets would send me something for helping them win,” he told his SABR biographers. He was no more than half-serious. I don’t know if he was any less.

Tommy Davis’s career was about half-over when he left the Mets. He may not have been in the best mood when he was told his tenure at Shea would be limited to one year. “Puppets have no feelings,” he said in the middle of December 1967. “We just have to go where our livelihood is. I’m glad to go with any major league club that wants me.” Yet, by the reckoning of Joe Donnelly in Newsday, Tommy was putting a stoic face on the situation because “a few nights” before the transaction, Davis declared, “I want to stay with the Mets. The club has been great to me. The fans, well, they’re unbelievable. I want to be an Ernie Banks.”

Banks had been a mainstay with the Cubs since 1953 and would be through 1971. Even in 1967, before the reserve clause was lifted, that kind of staying power was tough to cobble together for a baseball player, no matter how immortal. Banks would stay in one place. Mays wouldn’t. Hank Aaron wouldn’t. Frank Robinson had already been traded once and would be traded again. Tommy Davis was going to his third team. The second team, despite not being ready for prime time, gave Tommy the time he needed to prove himself anew. “By having a decent year,” he reflected in 2011, “I was able to play until 1976. I was certified good enough to play, thanks to 1967 with the Mets.” For that reason, Davis told his SABR biographers that he considered 1967, regardless of the ring he earned in 1963 (and the ring he wouldn’t be sent in 1969), the most significant year of his career.

Prospective contenders would continue to covet Tommy Davis, and he moved town to town, up and down the standings, forever a cog in somebody’s machine (though never Cincinnati’s). After his year with the White Sox, there’d be stints with some pretty good to very good Astros, Cubs, A’s, Orioles and Royals clubs, along with the Angels as he approached the end of his line. The Yankees, who missed out on him in 1956 when Jackie Robinson convinced him to be a Dodger, gave him a Spring Training look-see on the eve of their pennant run in 1976. “The designated hitter is taking care of this old man,” he said as he reached the twilight of his career. “It sure has helped me bring home the paychecks.”

In 1969, there was a stretch with the expansion Seattle Pilots, meaning there was a supporting part for him in the most influential baseball book of the twentieth century, a project to which he gave his blessing (not every ballplayer mentioned was so generous). “Jim Bouton was my teammate in both Seattle and Houston,” Davis told This Great Game in 2005, “and he mentioned me a few times in his book, Ball Four. […] Many players believe that anything that happens in the locker room should stay there, but I’m not an advocate of that. But, I’m not mad at him and I never was, because everything he wrote was accurate and he was honest. I know the Pilots manager Joe Schultz thought it was a distraction, but I thought it was well-written and damn funny.”

In all, Davis played one game shy of 2,000 and recorded more than 2,100 hits. He retired in the winter of 1977, just as the first class of free agents was able to hit the market and find the best deals for themselves. For many years, he’d work in community relations for the Dodgers, even if the Los Angeles community wasn’t initially his home. To be fair, even when he missed New York, he did admit he adored the Pacific Coast weather. No doubt the SoCal sun shone brilliantly on Tommy Davis when his star shone brightest. When he died, he was remembered primarily for what he did in 1962 and 1963. Still, we shouldn’t forget the year of his professional life he gave us in 1967. I’d say that even if I didn’t always love that baseball card.

Greg, what a beautiful piece of writing this is. Thank you

Thank you, Steve.

Excellent piece, Greg.

I always knew that Tommy Davis played for us for 1 season, 1967, and hit .302.

And always wondered why they ever traded him. It is great to see the backstory behind all this, and how he felt about all of it. Loved his puppet quote.

And BTW, Ball Four is one of the funniest books there is, baseball or otherwise. And Bouton’s sitcom of the same name, co-starring Ben Davidson, was….. I don’t know, I can remember watching the few episodes they made, and that was that.

Thanks, Eric. Tommy Davis seemed to relish speaking his mind during and after his career. He left behind a rich archive of his thoughts to go with all those base hits.

I was excited to watch Ball Four…untilI watched it.

Greg: Thanks for the great over-view of Tommy’s career. The Mets have a history of mis-judging talent, in and out, and Tommy could have been part of 1969…I saw him play basketball for Boys High in 1956.

https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/tommy-davis-left-his-mark-on-my-buddy

GV

Much appreciated, George. Thank you for helping us understand this fascinating person and fantastic player then and now.

Tommy’s obituary in the Times did not do him justice. Yours did! Exceptional writing!

See you on Opening Day. Let’s go Mets!

Thank you, Paul. Davis’s one year at Shea seemed worthy of a little deeper examination than it was getting in other corners.