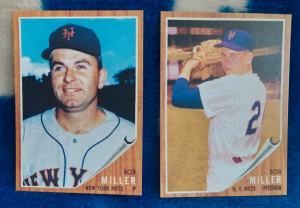

Let’s be honest. Unless you were keeping close tabs on Casey Stengel’s bullpen between July 24 and September 18, 1962, you probably don’t have any idea what kind of pitcher Bob G. Miller was for the 17 appearances he made in a New York Mets uniform. But, to be fair to all concerned, you don’t really have to know what Bob G. Miller did in his twenty-and-a-third innings on the mound to have an idea of who Bob G. Miller was in the Original Mets’ narrative.

He was Bob Miller. Not that Bob Miller. The other Bob Miller. Or vice-versa.

Yeah, you know about Bob G. Miller, lefty complement to the righty known as Bob L. Miller (Bob L. Miller’s birth name was Gemeinweiser, but he changed it because “I couldn’t pronounce it myself”) in every mythic recapitulation of the goofiest season the 20th century ever yielded. Or would that be every goofy recapitulation of the most mythic season the 20th century ever yielded? Both apply. Both Bob Millers pitched for those Mets. Both slept in the same room on the road. It was easier that way. As traveling secretary Lou Niss explained (captured in Dave Bagdade’s authoritative, all-new revised edition of A Year in Mudville), “If somebody calls for Bob Miller, he’s bound to get the right one.”

Or the left one.

It’s easiest to simply have a good laugh when reminded that once Bob joined Bob, Casey couldn’t keep them straight. Then again, he probably didn’t devote a lot of energy to sorting Millers. Stengel started in professional baseball in 1910. He hadn’t reached his sixth decade in the game, achieving legend status in the process, by getting bogged down in details.

Thus, as the story goes, when Stengel wanted the righthander Bob Miller to come into a game, he sent instructions to the bullpen to get “Nelson” up. Why was Bob L. Miller “Nelson”? Wasn’t Nelson the fellow in the plaid sports coat in the broadcasting booth? However the thinking went, the system worked. Well, the Mets lost 120 games, but the right (or appropriate) arm sprang into action.

For Bob G. Miller, the lefty in case you’ve lost track, the arm produced two wins of the Mets’ forty, not bad considering this Bob was enjoying life as a Cincinnati Red, oblivious to the standards soon to be set for futility in Upper Manhattan. But the Mets wanted to unload Don Zimmer and found a taker in Cincy: Zim for Cliff Cook and Miller. Miller, whose major league bona fides went back to 1953, wasn’t necessarily looking to continue his career in New York. He had his eyes on going into business. But he was talked into sticking with his craft for service time purposes. Pitch a little longer, he’d pile up enough days to qualify for the pension. That made bottom line sense to the budding executive. Bob G. Miller reported to Syracuse and pitched himself back into National League shape.

One of Miller the portsider’s wins as a Met, on August 4 at the Polo Grounds, came in relief of Miller the starboarder. Righty Bob, with the club since April, was 0-7 at the time, having pitched in the only luck the 1962 Mets had in abundance: tough. He’d gone seven innings and given up two runs. It wasn’t enough to ensure victory. The game would wind on to a fourteenth inning. Its top was pitched scorelessly by Lefty Bob. Its bottom was capped by a Frank Thomas home run (Frank Thomas the 1962 Met, not Frank Thomas the 1990s White Sox superstar). Pitcher of record? Bob Miller. Not that one; that one. Righty Bob — who would live only until 1993, when he perished in a car accident at 54 — had been waiting since April for a W to fall into his lap and would have to wait until the final weekend of the season to raise his record to 1-12. If he couldn’t get it for himself, at least it went to a fella with whom he shared a name, a box score and accommodations.

Whereas Bob L. Miller’s career would continue through 1974 (concluding with a second stint as a Met), Bob G. Miller put in his Met time, logged his pair of wins, earned his pension, and retired from the game after 1962, making him one of nineteen players on that first-year roster whose big league career ended, whether by mutual or unilateral decision, prior to 1963. The lefty was ready to move on to endeavors that didn’t need to distinguish a person by dominant arm. Before he died this past week at 86, the ol’ southpaw could look back on his post-Mets life with pride. He succeeded in business, dedicated himself to philanthropy, served his community, and raised a loving family. He also found time to chair the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association, making it his cause to help those players who weren’t able to put in the requisite time to qualify for a pension.

For being one of the two Bob Millers whose name we recognize with an inevitable gleam of mischief, we appreciate that Bob G. Miller stopped by for those couple of months.

The primary font on this book cover, as was the case on so many paperbacks and record albums of its era, was created by graphic artist David West.

His name was David West. Like “Bob Miller,” it may sound unassuming to you, but you have to understand that David West is, at least on genealogical paper, my father-in-law. Not the David West in the Mets’ system, of course. David West the pitcher and I were roughly the same age. David West my father-in-law was born decades before. He also, quite sadly, died nearly a decade before I met his daughter. That David West was also essentially a name to me, but obviously so much more. That David West, I would learn, was a splendid graphic artist and a kind soul. I know about the first part from examining his portfolio. Chances are if you’ve ever picked up a few mass-market paperbacks or popular albums produced in the 1960s and 1970s, you saw the fonts David West created grace their covers. The kind soul part is vouched for by Stephanie, who certainly inherited that character trait, among others. My wife has quite the artistic bent. I know where she got it from.

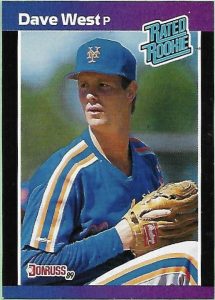

Rooting for David West the pitcher was second nature to me as he approached his debut in September 1988. At 6-foot-6, he was a big lefty, though hardly the only one preparing to impose his will on the National League East that month. Randy Johnson was called up to the Expos around the same time. Johnson was merely categorized as a big lefty, perhaps of the extra large variety (6’ 10”), but he was not yet the Big Unit. Randy fanned nearly a batter an inning in Triple-A in ’88. David recorded a 1.80 ERA in 23 starts at the same level. Big things were expected from each towering figure. They arrived on the scene almost simultaneously. According to Baseball-Reference, Johnson was the 15,571st major leaguer ever in terms of debuts. West was the 15,579th.

The Mets didn’t see Randy Johnson that September, so I didn’t worry about what Montreal had in their hurler. We didn’t see what the Mets had in David for a spell after his promotion as they were busy getting their division clinched and sticking with known quantities. On September 22, they made their fourth NL East title and second in three years official. On September 24, with nothing much at stake, Davey Johnson turned the keys over to the 24-year-old who’d shared Doubleday Player of the Year honors with batterymate Phil Lombardi at Tidewater, giving him a Saturday afternoon start in St. Louis.

David West indeed lived up to his notices in that he was very much a big lefty. He was also unpolished relative to those we’d been watching pitch all season. The 1988 Met staff posted a collective ERA below three. Their five main starters — Gooden, Cone, Darling, Fernandez and the suddenly unavailable Ojeda (the hedge clipper incident) — took the ball 158 times, going 77-44 as a pretty big unit themselves. Bobby O’s finger injury notwithstanding, Mel Stottlemyre didn’t exactly hang a neon HELP WANTED sign outside Shea that season. Even if West had overwhelmingly impressed in his initial start, it was too late to crash the postseason roster.

Young David was staked to a 3-0 lead in the top of the first; brushed off a Vince Coleman single and Ozzie Smith walk in his initial half-inning of work; and saw his edge extended to 6-0 in the top of the second. Kevin McReynolds, Tim Teufel and Mookie Wilson had each homered to provide him a comfortable cushion. That’ll calm a nervous rookie, and I definitely remember West appearing nervous, lacking command. Maybe he came across as tenuous by comparison to our poised corps of incumbent starters, or maybe it was because I was rooting a little extra hard for “David West,” but I worried for him. The line from his first outing indicates a rookie who acquitted himself just fine: five innings, five hits, two walks and only one run allowed. The Mets scored 14. David, who chipped in a single and double (“I got lucky”), was a 1-0 pitcher. What he didn’t show in terms of command he seemed to have going in terms of perspective: “I did OK,” he said. “I’m pleased. I wasn’t that sharp, and I can throw harder. But I’m happy. I wasn’t trying to make the team. I just wanted to do well.” Perhaps the Met prospect with the name I couldn’t resist embracing was going to be a part of this rotation for the long haul.

It didn’t work out that way. David never had a particularly wonderful outing, starting or relieving, as a Met again. But he was still a big lefty and enough of a prospect to entice other teams. The Minnesota Twins were looking to detach themselves from the contract they’d given their Cy Young winner Frank Viola. The Met rotation had a HELP WANTED sign blinking by the summer of 1989, flashing furiously once Doc went on the DL. A trade was made: West, Rick Aguilera, Kevin Tapani and a couple of minor leaguers who’d never made it to the Mets — Jack Savage and Tim Drummond — for Viola. It was a five-for-one blockbuster that indicated the scuffling contenders were serious about returning to the top of the East.

From a New York perspective, it became one of those trades that sort of worked out until it didn’t. Viola pitched well but with not enough support in star-crossed 1989, got off to a blazing start in not-quite 1990 en route to 20 wins (though he had a nagging habit of pitching just well enough to lose down the stretch), and ran out of effectiveness as his final season at Shea wound down in 1991, though the same could be said of the entire operation. Meanwhile, in Minneapolis, the Twins were gathering momentum and rolling toward a world championship, with lockdown closer Aguilera saving 42 games, reliable starter Tapani notching 16 wins and West each contributing to the cause. A trade worth making became a trade tinged with regret. Between 1991 and 1996, Met and regret rhymed a lot.

West wasn’t the only big lefty rookie traded out of the National League East in the midst of the 1989 season, just as Frank Viola wasn’t the only established lefty traded out of the American League West. Actually, Frankie V wasn’t the Mets’ initial target. Seattle had been looking to move Mark Langston. The Mets wanted him, but lost the Markstakes to Montreal, which parted with a trio of pitchers that included Randy Johnson. Sweet Music became the Mets’ fallback option, albeit a pretty damn good one. Langston, like Viola, pitched well enough in what became a losing cause in terms of winning a division. Johnson became Johnson. He became the Big Unit and all that would come to imply. His massive success wasn’t instantaneous, but it goes down as inevitable. Randy Johnson is in the Hall of Fame today.

David West never came close. He had a fairly lengthy career, pitching in the majors until 1998. He went back to the World Series with the Phillies in 1993. There was nothing to not respect from his big league tenure, even if it didn’t near the plane of a Randy Johnson or didn’t quite live up to whatever winning a Doubleday Award was supposed to imply. He was still David West, a name that still means something in my heart.

My future father-in-law died before he turned 50. The pitcher with the same name, who endured a battle with brain cancer, didn’t make it to 60. Neither did Phil Lombardi, come to think of it. Lombardi, who caught for the Mets in 1989, was born in 1963 and died in 2021. West of the Mets, Twins, Phillies and Red Sox was born in 1964 and died in 2022. I was born in 1962, so I may be a little sensitive to passings in certain demographic circles.

Randy Johnson retired in 2009 with 303 wins. David West was done more than a decade earlier, having won barely more than a tenth of that total. Yet when I think of that David West, I think of the David West who, without ever knowing me, gave me the biggest win I’d ever have. So I gotta say, when you combine the records of the two David Wests, they did OK by me.

My goodness, I hadn’t heard about David West’s passing, that’s sad news. He always appeared kind of sad to me when he was a Met. After Doc and Darling and Sid and Aguilera, the buzz on West was “wait til you see this guy,” but he was a lot closer to Jeff Bittiger than he was to Dwight Gooden in terms of turning potential into major league performance. Always looked disappointed in himself, body language seemed to say “I don’t know what to do.” That’s a shame, RIP.

Glad to turn the page on the month of May, as it was a tough one for Met fans.

Piggy, West, “Nelson(?),” and Roger Angell, and John Stearns appears to be deathly ill with some horrible disease.

Google some photos, and he looks so skinny as to be unrecognizable.

Good Luck, Bad Dude.