Max Scherzer pitched seven innings of shutout ball on his 38th birthday. Of course he did. He was born to put up zeroes on the night of July 27 in the borough of Queens before a sold-out house in attendance to cheer on a first-place team. It was foretold when he first drew breath and presumably glared a pea-sized hole through the forehead of his mother’s obstetrician.

July 27, 1984, wasn’t just any date in New York Mets history. It was a double-dip. We’d someday dip into Steve Cohen’s discretionary funds and sign the best pitcher ever born on said date, but that was a bunch of decades off. In the moment, as the Scherzers were mulling what to name their newborn in St. Louis (likely paying scant attention to the fifth-place Cardinals pulling out a tenth-inning victory over the sixth-place Pirates in Pittsburgh), Met fortunes were situated in the right palm of a pitcher roughly half the age of what Max would turn on July 27, 2022.

Dwight Gooden was pitching at Shea Stadium on a Friday night. That alone says so much, but on July 27, 1984, Dwight Gooden was pitching at Shea Stadium on a Friday night against the Chicago Cubs. That says even more. The New York Mets were in first place for the first time at such a late juncture in a season since 1973. Dwight was eight then. He was 19 now. The Mets had been nowhere as the kid from Tampa finished elementary school, junior high and high school. The Mets were so nowhere that they were able to draft Dwight Gooden, then 17, with the fifth overall pick in 1982. The Mets stayed nowhere until 1984, which not coincidentally is when we met young Dwight.

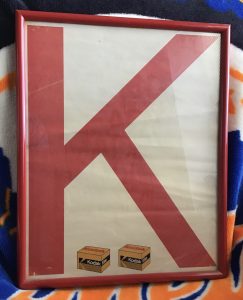

We called him Doc, as in Doctor K. You remember the unofficial last name. If you needed a reminder, you could glance up above left field at Shea. All the strikeouts Doctor K recorded were dutifully documented by fans who couldn’t wait until the next morning’s box score to know the total.

“In the left field upper deck, ‘the K Korner’ is open for business,” Joey Johnston wrote in Gooden’s hometown Tampa Tribune when the local product was tabbed to pitch in the All-Star Game. “Dennis Scalzitti and Leo Avolio, lifelong Mets fans from New Jersey, hang ‘K’ posters on the railing each time Gooden whiffs an opponent.” At two strikes, Johnston elaborated, “They wave the ‘K’ above their heads, inspiring the crowd to stand and cheer, urging Gooden to finish the strikeout.”

He did that a lot as a rookie. The rookie professed no great concern with his strikeout volume, which would add up to 276 by season’s end. I don’t worry about the ‘K,’” he said in early July after inspiring Scalzitti and Avolio to hang a dozen of them. “My purpose is to win games and help the team.” The Mets benefited from that attitude and that talent. Gooden lit up the All-Star Game on July 10 and kept electrifying the National League en route to the July 27 showdown versus the Cubs. It’s no wonder attendance spiked every time Gooden pitched at Shea. It’s no wonder that every seat was spoken for this time Gooden was pitching at Shea. The Mets were 3½ games up on the Cubs after a midweek sweep of the Cardinals, presumably to the dismay of Brad Scherzer, an expectant dad whose home team had fallen precipitously since trading Keith Hernandez the year before. Keith thought he was going to baseball Siberia on June 15, 1983. He wouldn’t have guessed baseball Paradise would be under construction thirteen months later.

On July 27, 1984, Doctor K kept the K Korner engaged, if not overwhelmed. More importantly, he kept the Shea scoreboard operator on a consistent keel. Doc allowed 1 run in the top of the first inning to the Cubs. The Mets answered back with 1 in the bottom of the first. And then, starting with the second, the top line looked like this:

“That was the hardest I have seen him throw all year from start to finish,” said Hernandez, whose St. Louis affiliation belonged to a very distant past by July 27, 1984. “He didn’t have a curve at first and then it came to him. When it did, it was a hard curve. He had trouble keeping his fastball down at the start, but then he got it. That’s not a fastball he throws. Looking at it from first base, it’s a blazer. He’s like Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson,” the latter the all-time favorite pitcher of Brad Scherzer. “He gets better as the game goes along.”

Backman agreed. “He keeps us in the game,” the second baseman said. “Dwight had a little trouble at the beginning but he started to go through them like so many high school players later on with his fastball and curve.”

Gooden won the game and helped his team. The Mets were 59-37, the most they’d been above .500 all year, the most they’d been above .500 since the end of 1969. They were 4½ ahead of the Cubs, another high water mark through 96 games. The National League East might as well have been made up of Hillsborough High School’s opponents back in Tampa. Doc indeed made everybody look like an amateur by comparison.

July 27, 1984. The date has stayed with me for 38 years. It would never get any better for the 1984 Mets after that night. They’d never be as many as 22 games above .500 the rest of the way. They wouldn’t lead the Cubs by as many as 4½ again. Soon they wouldn’t lead them at all. Yet 1984 gets a pass in the mind’s eye. It was the year the club came into its own, the year Doc burst on the scene (Rookie of the Year winner, Cy Young runner-up), the year Keith settled in (second in MVP voting). Keith remembered it well on July 9, 2022, when the Mets retired his number at Citi Field. The flag that flies over the right field porch says 1986. The great leap forward was 1985. But 1984…you never forget when the chronic losing stops and winning becomes habit-forming and hope is a legitimate instinct.

“When I went to Spring Training in ’84,” Keith recounted, “and I saw the group of talented athletes, all young, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, lookin’ up at me, I knew we had something special. And we did. […] All these young guys — Darryl, Doc, Ron, Walt, Ed, Mookie, Roger, Fitzy and Jesse — they rejuvenated my career.” They rejuvenated us, too. No, you don’t forget that.

Max Scherzer would live up to his purpose and help the Mets win the game. It was the game he was born to wrap his mitts around. At least until his next start.

Max threw six pitches in the first inning at a sold-out Citi Field. He registered three flyouts, retiring DJ LeMahieu, Aaron Judge and Anthony Rizzo in order. You look at those names and a run has already crossed the plate most nights. But then you look at Max Scherzer’s name.

Pete Alonso’s name and swing were good for a leadoff homer against Domingo Germán in the second. Francisco Lindor, who plays as if he circles the Subway Series in his day planner every January 1, provided a second run by driving in Tomás Nido from second in the third. Nido’s purpose was catching Scherzer. Anything he does with a bat is a bonus. A second run is a bonus sometimes when the Mets decide their ace pitcher can do it all. Two translated as twenty the way Max was going. He wasn’t dominant along the lines of 19-year-old Gooden. He was dominant along the lines of 38-year-old Scherzer. Two walks, five hits, a “mere” six strikeouts in the eyes of whoever will never be able to watch an all-time strikeout artist and not think of the K Korner, especially when the pitcher is Scherzer and the whiffer is Judge (indeed, three of those Ks were foist upon Hammerin’ Yank Aaron). Most importantly:

I was pretty certain Max Scherzer wasn’t going to get anywhere near the mound in the ninth inning on July 27, 2022, because that hardly ever happens anymore, no matter that your name is Max Scherzer and your credentials are Max Scherzer’s. But after revisiting the events of July 27, 1984, in advance of Scherzer’s start, and as I considered the more than one inning apiece pitched by Adam Ottavino and Edwin Diaz on July 26, 2022, I sorely wished Buck Showalter would give Max the slightest nod toward the field after the Mets batted in the seventh. Scherzer wouldn’t need more than a hint. Hell, Buck wouldn’t have to finish his nod before Max would be throwing to Nido.

Again, however, that’s not how it works. Nor are two runs that look so mighty when Max is on the mound, even against the Yankees, look like much when it’s anybody who isn’t Ottavino or Diaz facing them in relief. Sure enough, the so-crazy-it-might-work experiment of handing David Peterson the eighth inning imploded on contact, first figuratively via a four-pitch walk to Anthony Rizzo, then on the fifth pitch of the inning, a two-run gopher ball to Gleyber Torres. All that Gooden-Scherzer symmetry was suddenly relegated to footnote status unless Showalter was hiding somewhere within his windbreaker a rested reliever who could avoid any further mess.

Son of a Buck, the manager had an answer. After Peterson recovered just enough to strike out Matt Carpenter, Showalter called on Seth Lugo, who used to inspire all the bullpen confidence circa 2019, when the question wasn’t why Seth Lugo? but why Seth Lugo for only one inning? Vintage Six-Out Seth Lugo returned to form of yore by getting Josh Donaldson looking and Aaron Hicks swinging. Then, after the Mets continued to honor their pact of non-aggression where scoring was concerned in the bottom of the eighth, Lugo continued to pitch, bringing his returned form with him. Two outs at the bottom of the order, a single to LeMahieu and, oh joy, Judge up as the potential destroyer of worlds.

Except Lugo grounded Judge to short, forcing LeMaiheu, and if the Yankees couldn’t take advantage of a ninth inning in which Diaz’s trumpets didn’t blare, maybe we wouldn’t have to see extra innings. Maybe, instead, we’d watch Eduardo Escobar see his offensive shadow for a change and belt a double to deep left; Nido unearth the ancient art of the sacrifice bunt to put Eduardo on third with less than two out; Brandon Nimmo not do exactly what we wanted but not do anything detrimental (he reached on a comebacker that Wandy Peralta couldn’t quite tame); and Starling Marte do exactly what we wanted.

It took two pitches for Marte to send a single into left and Escobar home from third. A tense Wednesday night tie became a jubilant Subway Series sweep. Just like that, the Mets were 3-2 winners and possessors of a record of 61-37, the second time in 2022 they’ve been as many as 24 games above .500. Coming into the two-game intracity set, they were 59-37, the exact same mark the 1984 Mets had on July 27, 1984. As noted, the Mets fell from 59-37, taking our division championship dreams with them, at least until that December when Walt was traded to Detroit for Howard Johnson, and Fitzy was part of a package going to Montreal for Gary Carter, and we got back to dreaming suitably big mid-1980s dreams.

These first-place New York Mets keep building on what they’ve accomplished. They’ve been doing it from Day One of this season. They’re still doing it. They have to keep doing it, not only because the second-place Atlanta Braves, currently three games behind us, are as formidable an opponent as the 1984 Cubs or 2022 Yankees, but because there’s little chance somebody will stand before a throng of Mets fans 38 years from now and wax rhapsodically about the 2022 Mets who showed what a group of talented athletes — some if not all young, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed — they were unless there’s a payoff in October.

We don’t need to wait until 2060 for history’s judgment. To be remembered as something special, this team can’t peak in late July. This year hasn’t emerged as the start of something big. It is something big. A helluva spring and summer isn’t gonna cut it without a fall to match. Not after last year’s transitory occupancy of first place diminished for many among us the meaningfulness of leading the NL East prior to the completion of 162 games. Not after so many years since 1984, 1985 and 1986 when, honestly, there haven’t been many years like 1984, 1985 and 1986. A few good ones here and there. None presented in quite so satisfying a sequence. Maybe you can catch the rising stars only once in a lifetime.

Right now, you’ll never forget what it was like for Max Scherzer, Pete Alonso, Francisco Lindor, Seth Lugo, Eduardo Escobar, Tomás Nido and Starling Marte to have gathered their forces and beaten the Yankees in dramatic fashion. Whether you’ll more than dimly remember it a year or ten from now depends mostly on the next series in Miami; the series after that in Washington; what happens by next week’s trade deadline; the respective recoveries of James McCann, Trevor May and, oh yeah, Jacob deGrom; the five-game series at home against Atlanta; and then everything after that. It’s 38 years since 1984, light years beyond taking sentimental solace in the nicest of tries.

In a way, that’s too bad. In another way, that’s baseball like it oughta be.

A new episode of National League Town, pretending it knew all along the Mets would sweep the Yankees, is out now. Listen to it. It’s fun.

When I realized the game was on ESPN last night, I immediately chose to sync with Howie and Wayne. After the requisite messing about, I got as close as could be expected.

The next inning it unsynced. And the next. And the next. ESPN intentionally time shifts the live action to make the commercials and the CONSTANT cutaways work. Infuriating.

Turned on the radio, flipped to ESPN Deportes (muted anyway, so the language wasn’t a barrier), only a few seconds behind WCBS. No need to look up from my devices until Howie implicitly suggested it was worthwhile.

“It was well after Koufax and Gooden, but not far removed from Seaver and Carlton.” — Gibson?

For a change the Mets took advantage of the Braves slipping to expand the lead. After the lead dropped to .5, I was not confident the Mets would still be in 1st place today, let alone build the lead back up to 3 games.

Same situation post-season, including recent workload, I wonder if Scherzer tries to squeeze out 1 more inning and/or Diaz gets the call in place of Lugo.

Fingers crossed that deGrom feels fine through his throw and bullpen days and his next rotation turn will be for the NY Mets.

I hope Peterson figures out the relief role. It’s not an unusual role for young starters waiting for a rotation spot to open up, and the Mets need bullpen help. But his inability to relieve so far is passive aggressively helping to ensure his career isn’t diverted into the bullpen like Lugo’s.

Fingers overslid the keys. Fixed. Thanks.

I was not high on the Holderman-for-Vogelbach trade, but in the small sample he’s played for the Mets, he strikes me as the kind of non-star who delivers clutch in the post-season to carve his name in baseball lore.

[…] Born Under a K Sign » […]